The Bloomberg administration's garbage plan has been sitting on a shelf awaiting full implementation for four years, and some critics think it's on the verge of spoiling.

After extensive political wrangling, the administration and the City Council in 2006 agreed on a solid waste management plan, which shuffled the location of solid waste stations and relied on trains and barges for moving trash instead of diesel-spewing trucks. Though it was hailed as a major step forward for environmental justice at the time, four years later many of the plan's fundamental proposals have been held up due to permitting delays and lawsuits.

Eight rounds of budget cuts have devastated the Department of Sanitation's public outreach and education funds. The city hasn't even come close to meeting its recycling goals, which were supposed to be accomplished in 2007. And now we're sending more of our garbage to out of state landfills at a cost that has increased by 51.4 percent between 2000 and 2010.

To commemorate the 40th anniversary of Earth Day, the Bloomberg administration announced it would incorporate its solid waste management plan in its long-term sustainability vision — PlaNYC 2030. Environmentalists and garbage experts now say it's time to take another look at how the city handles the millions of tons of trash New Yorkers dispose of every year. Some of them argue we should throw out the city's original solid waste plan altogether.

A Garbage Plan

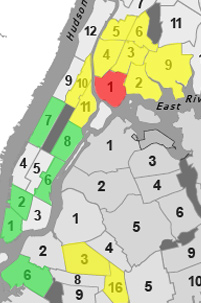

Following the closure of Fresh Kills in 2001, the city piled tons of dirty diapers, day-old take out and spoiled vegetables on to diesel trucks. Those trucks traveled to transfer stations in a handful of impoverished city neighborhoods and then sputtered to out of state landfills. The city's waste management plan was supposed to provide relief for those neighborhoods — particularly the South Bronx and central Brooklyn — which were saddled with most, if not all, of the city's garbage burden.

The plan put transfer stations for both refuse and recyclable materials in more affluent neighborhoods, including the West Village and the Upper East Side.

But since the plan's approval, two of the seven proposed city-owned stations have received the necessary state permits and are under construction, according to the Department of Sanitation. Only one is fully operational. According to the original plan, four of these proposed transfer stations should have been completed by 2010. Now, several won't be done until at least 2013.

Caught in the Courts

The state's permit process gets some of the blame for the delays. In addition, lengthy court and political battles have stalled transfer stations in affluent areas of Manhattan. As a result, the vast majority of the city's trash is still being trucked around the five boroughs and is still festering in low-income neighborhoods.

"The process has been slow, but not as a result, in this instance, of delays at the city," said Eric Goldstein, a senior attorney at the Natural Resources Defense Council. "There was hope that it wouldn’t take a full decade to really advance the barge and rail transportation ... It does seem now to be heading in the right direction."

But not everywhere, according to environmentalists. One area slated for a transfer station is still trash collection-free. In the Upper East Side, the Gracie Point Community Council has filed a second lawsuit against the city to try to quash a marine transfer station slated for 91st Street across from the FDR Drive.

Standing at the corner of 91st Street and York Avenue in Manhattan, just one block down from the proposed site, Tony Ard, the chair of the Gracie Point Community Council, said the city had not reasonably considered how a transfer station would affect the community and its environment — from trucks congesting tiny side streets to the health of its residents. He pointed to the athletic fields next to the transfer station's proposed driveway, where kids from nearby schools play, and to the Upper East Side's air quality — the worst in the city, according to new data from the health department.

"We're not saying choose minority residential neighborhoods," said Ard. "It doesn't belong in any residential neighborhood."

Ard expects a decision from the Supreme Court in Albany any day now. If it doesn't come down in the community's favor, he said, this isn't over.

"We're going to keep at this until we have no more courts available to us and no more legislatures," said Ard. "Why? Because it's wrong."

A spokesperson from the Department of Sanitation said the city carefully considered the public health and welfare when selecting transfer station sites, and the city has proved that the station is reasonable and necessary at 91st Street.

Other parts of the city's solid waste plan have moved forward. Twenty-year contracts have been either negotiated or are in effect with Waste Management of New York to export trash from Brooklyn, the Bronx and Queens. The sanitation department is currently negotiating with the Port Authority of New York and New Jersey for a long-term contract to take the vast majority of Manhattan's refuse to a waste-to-energy plant in New Jersey.

At the time of the solid waste management plan's approval, the administration argued long-term contracts would save the city money, and it would get the city's trash off of dirty diesel trucks. Almost 90 percent of city trash, the mayor promised, would be sent by rail or barge instead.

According to the Department of Sanitation, the cost of exporting the city's trash has increased per ton from $61.30 in 2000 to $92.80 in 2010 — a 20 percent increase over the rate of inflation. As of April, 33 percent of the city's trash has been unloaded from trucks and put on rail cars — an increase from 14 percent in 2006, according to the solid waste plan.

None of the city's waste is currently exported by barge, according to the Department of Sanitation, because those transfer stations have not been completed.

Dismal Recycling Rates

Politics may have held up parts of the city's garbage plan, but ordinary New Yorkers bear some of the responsibility for the city's failure to meet its recycling goals.

By 2007, according to the solid waste management plan, the city was supposed reach a 25 percent recycling rate for residences and a total rate citywide of 35 percent. According to the Mayor's Office of Operations, only 15.9 percent of trash was diverted from the residential waste stream for recycling so far this fiscal year, and only 24.6 percent of trash was recycled citywide.

Bottom line, New Yorkers aren't recycling like they should be.

"It’s a combination of a lot of things and to find out the answers to those things you have to spend a lot of money," said Robert Lange, the city's director of the Bureau of Waste Reduction, Reuse and Recycling, of the city's dismal recycling rate. "We only have two tools at our disposal: One is public education and one is enforcement. Clearly a lot of elected officials are not in favor of enforcement, including the City Council."

The problem is worse in some communities more than others. Public housing facilities have fetid recycling rates, said sanitation officials. If you dropped by Melrose or Port Morris in the Bronx during fiscal year 2009, less than 5 percent of the trash at the curb was set aside for recycling. Ten other neighborhoods, including Brownsville, Bedford Stuyvesant, Harlem and Hunts Point, put between 10 and 5 percent of their trash out for recycling in the same time period, according to the mayor's management report. Those neighborhoods also typically have the lowest median incomes in the city.

At the start of the Bloomberg administration, the city recycled more than 330,000 tons of metal, glass and plastic. In fiscal year 2009, about 231,000 tons were recycled — a decrease of 30 percent.

Officials in the Bloomberg administration and at the City Council are now turning to more regulation to boost the volume of clear plastic bags on city streets. Last month, Council Speaker Christine Quinn announced a package of legislation aimed at increasing the city's recycling rate, including a proposal to expand the types of plastics the city recycles. A bill, which has widespread support among the council, would add rigid plastics, like yogurt cups and take-out containers, to the city's recycling program. Another bill would establish textile-recycling drop off locations throughout the city, and another proposal would start hazardous waste collections for toxic household products. The council is also exploring forcing the city to study the feasibility of a widespread composting program.

The Department of Sanitation has expressed support for the vast majority of the ideas.

While advocates champion the proposals, some say there is still a long haul ahead.

Waste in a New Century

Now that the administration has decided to incorporate its solid waste management into PlaNYC 2030, advocates say the city should rethink the entire waste cycle: from the packaging of products to the 500-mile journey to a landfill down south.

"The revision of PlaNYC and the fact that solid waste is being brought into that plan now provides the opportunity to look at these issues of ultimate disposal and land filling and waste reduction," said Andy Darrell, the New York regional director for the Environmental Defense Fund.

Start with a carrot: use the city's buying power to curtail the amount of packaging of certain products, said environmental advocates. Concentrate on recycling construction materials, others add. (During his address in Times Square on Earth Day the mayor said the city would look into waste reduction.)

Other refuse experts are willing to use a stick instead.

"We need to work through the system step by step," said Benjamin Miller, an author and former director of policy planning for the Department of Sanitation. "We should prevent as much waste as we can. The single most effective system to do that is to charge people for the waste they send out."

Once the city's waste has been reduced, advocates say the administration should consider its far larger challenge: exporting trash.

A majority of Manhattan's trash goes to an incinerator in Newark, but the rest of our refuse is sent to quickly filling landfills out of state — in the far reaches of Pennsylvania, Ohio, Virginia and South Carolina. Set aside the environmental hazard of landfills for now, advocates say. Consider this: As these garbage pits fill up, it costs more for New York City to reserve space for its trash — hence the 20 percent increase over inflation in the cost of exporting refuse.

A solution, Miller argues, would be for the city to explore another waste to energy facility in the metropolitan area. Once extremely controversial, this technology, some environmental advocates say, has caught up with the industry, and now incinerators that burn trash and convert it to usable energy are much cleaner than they used to be. The idea is not palatable to all of the city's environmentalists, like Goldstein. And it too would come with a hefty price tag.

Clean solid waste management may be a foreign concept to some. But ultimately, experts say our trash piles need to go somewhere, and Southern hospitality won’t last forever.

"There aren’t many good things you can do with garbage at the end of the day," said Darrell. "We're a city of between 8 and 9 million people. We generate a lot of trash."