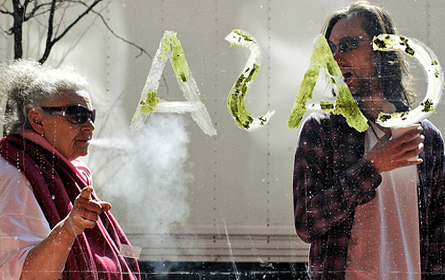

Smoking in New York City parks, beaches, and pedestrian malls became illegal last week. At a public hearing when the ban was proposed last fall, the city's health commissioner, Thomas Farley, predicted, "In the future we will look back on this time and say, 'How could we have ever tolerated smoking in a park?'"

Farley is almost certainly right. Public attitudes toward smoking have changed so thoroughly in the last 40 years that the smoke-filled offices depicted in "Mad Men" are barely recognizable. It’s likely that a few decades from now, if not sooner, the idea of smoking in a park will seem as outlandish as lighting up in an elevator or a supermarket -- the first public spaces in New York City where smoking was prohibited, 37 years ago.

Extending the Limits

It was in the spring of 1974 that New York City's health commissioner tried to ban smoking in "places of public gathering," such as restaurants, theaters, museums, libraries and hospitals. It was a radical proposal. Almost 40 percent of U.S. adults smoked, around double the rate today.

The resistance to the proposal was so intense that the law was dramatically weakened on the way to passage; the ban was whittled down to cover only elevators and supermarkets "There will be no more ashes flicked on raw meat in the meat departments," the commissioner, Lowell Bellin, said.

Over the following decades, however, public tolerance for smoking eroded, and most public spaces became smoke-free. Opinion polls have shown overwhelming support for the increasing limitations, even among smokers themselves.

Taking It Outside

Extending bans from enclosed spaces to outdoor areas represents a new phase. Yet a common thread connects the first restrictions on indoor spaces passed in the 1970s to the new laws on parks and beaches that have become increasingly common across the country: All these bans have dual rationales, but only one is usually acknowledged.

The first and most prominent rationale is to protect non-smoking bystanders from secondhand smoke. At first, this reasons was based more on suspicion than fact -- the scientific evidence of the dangers of secondhand smoke was scant in the early years of tobacco control -- but eventually studies demonstrated that exposure to the smoke of others was associated with elevated risk of cancer, heart disease and other illnesses.

The second purpose behind smoking bans, then and now, is less often acknowledged but almost equally important from the standpoint of public health: changing public attitudes. To reduce the toll of illness and death from cigarettes, tobacco foes sought to transform smoking from a glamorous, desirable behavior to a stigmatized, unacceptable one. In political debates over bans, this rationale was often soft-pedaled, although a few public health officials were blunt about their goal. Said Bellin when he was New York's health commissioner in 1974, "We hope to create a climate in which the smoker is uneasy."

The Power of Stigma

Bans on smoking in indoor spaces are unquestionably justified on health grounds. Outdoors, however, air-monitoring studies have shown that cigarette smoke dissipates and poses little risk to anyone more than a few feet away.

So it's clear that, whatever health claims proponents may make, the intent of banning smoking in parks is a social one: to "de-normalize" smoking. Testifying last fall on New York's law, health commissioner Farley made this clear when he said, "Parents should be able to bring their children to parks and beaches knowing that they won't see others smoking."

Some critics see this use of the law as unjustified, even sinister. But it's important to remember that the social climate decades ago when smoking seemed natural didn’t come about naturally -- it, too, was engineered. Throughout the 20th century, tobacco companies with vast resources at their disposal used aggressive marketing and advertising to portray smoking as a symbol of glamour and sophistication.

Public health advocates seeking to halt the epidemic of tobacco-related illness don't have anywhere near the financial clout that the tobacco industry does, but they can shape public opinion through laws and regulations. Banning smoking in public places such as parks and beaches sends a powerful symbolic message that smoking is unacceptable, even in situations where it poses no direct health risks to others.

James Colgrove is associate professor in the Center for the History and Ethics of Public Health at Columbia University's Mailman School of Public Health and author of Epidemic City: The Politics of Public Health in New York (Russell Sage Foundation, May 2011).