Let’s start with this inescapable fact: If you are a Mexican immigrant living in Port Richmond on Staten Island you are being targeted by some black young people.

There have been 11 such attacks since April and another on a white gay married couple. The violence has attracted citywide and national attention in what is being called an epidemic of bias-related crime. Such assaults are proliferating on Staten Island’s North Shore.

These incidents have revived debates over what constitutes a hate crime, whether these attacks are borne out of bias, whether enhanced penalties are just and effective, the roots of the tensions, and what the response should be.

I write as a Manhattanite who has done work and played on Staten Island but who must relay mostly on the testimony of native islanders to get this story.

It turns out that the tensions are by no means a new story, even the black-on-Mexican attacks in Port Richmond. Debbie Nathan documented similar neighborhood conflicts for City Limits in an article called "Race Wars" in 2004, questioning the “hate crime” paradigm.

But never has more attention been paid to it.

The Tensions Beneath

Staten Island has changed over the years from a bastion of insular white conservatism to a multiracial borough with an increasingly progressive bent. You only have to ride the Staten Island Ferry -- as I did on a recent Saturday night -- to see African Americans, Latinos and Asian residents.

The boat I rode was named for former Staten Island Borough President Guy Molinari. In 1994, he infamously declared Karen Burstein, the Democratic nominee for state attorney general, “unfit for public office” because she was a lesbian. Today one of Staten Island’s Assembly members, Matthew Titone, is an out gay man and one of its City Council members, Debi Rose, is African American.

And Staten Islanders embrace this.

A white woman on the ferry named Israela called the current crisis “crazy.” She said of the perpetrators, “Their parents should talk to them.”

Daphne Burton, an African American woman from Queens going to the island for a visit with her grown children, said of the situation, “We all have a right to be free, but a lot of people don’t look at it like that.”

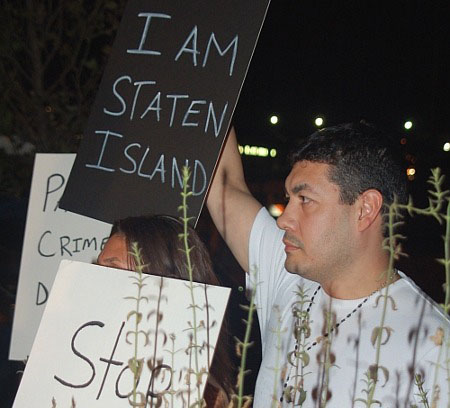

Staten Islanders and public officials have turned out in force to denounce the attacks. A broad and diverse coalition of elected officials and groups has started the “I Am Staten Island” campaign to “take responsibility for ensuring the Island is a safe and welcoming borough for people of all backgrounds.” Their 10-point plan to address the crisis includes public and school education programs on tolerance, installing more security cameras, aiding attack victims, increasing recreational opportunities in the affected neighborhoods, and expanding intergroup relations efforts by religious groups and other community-based organizations.

As laudable as these efforts may be, they may not get to the heart of the problem or reach the young people behind the violence, some longtime residents and advocates say. Ana Maria Archila, co-executive director of Make the Road by Walking, an advocacy group with a presence on Staten Island, says Port Richmond’s is afflicted with a “total abandonment by government,” “disaffected African American youth” who have no employment or hope, “the fastest growing Mexican community in the city,” and a lot of “confusion and resentment.” She sees the current wave of violence as an outgrowth of anti-immigrant campaigns across the country.

“Every community has bad apples,” said Assemblymember Titone. But, he added, “Thugs probably don’t go to church and school and can’t be reached. They need to be apprehended.”

Council Speaker Christine Quinn, a former director of the Gay and Lesbian Anti-Violence Project, said that it is difficult to determine the source of this wave of violence. It could be economic factors, although theft did not occur in four of the 11 attacks. Nonetheless, she said, “No one should think we only have a problem on Staten Island.”

"A large response from all parts of society is a good thing because it sends a message to everyone who might want to act out against immigrants that the City of New York absolutely will not tolerate it,” Quinn said. She noted the I Am Staten Island group includes everyone from gay and lesbian groups to the Sons of Italy.

A Full Swing Response

The City and the FBI have responded with an increased police presence in Port Richmond.

But the most recent attack on a Mexican, Christian VĂ zquez, 18, occurred on July 31 while the show of force was in full swing. Police later arrested a suspect in that case, Derrian Williams a.k.a Romeo Stevens-- a 17-year-old Liberian immigrant. He faces 25 years in prison if convicted of all robbery and assault charges -- each charge could include additional prison time because his assault is classified as a hate crime. Police believe five men were involved in the attack.

The police response has not pleased everyone.

Archila of Make the Road said the constant police presence has hurt Mexican businesses whose customers, some of whom are here illegally, shy away from law enforcement. “There’s less crime,” she said, “but it doesn’t feel sustainable.”

Others question whether singling out these crimes is the best strategy.

Bill Dobbs, a longtime gay and civil liberties activist, said, “Criminal law cannot fix social problems. The cry for hate crime prosecutions is raised once again in Port Richmond but it cannot reckon with race relations or intergroup tensions. That requires hard work and community intervention Using the New York hate crimes statute also contains the seeds for backlash, creating resentment that some criminal acts are punished more severely because certain words were spoken during the crime.”

In the Other Boroughs

Crime is up in most categories across the city, but hate crimes have increased disproportionately citywide. According to the Daily News, hate crimes jumped from “111 to 200 through July 11 -- an 80 percent surge from the same time period in 2009.”

The police department did not respond to several requests for a breakdown of hate crimes statistics by borough. A representative from the Hate Crimes Bureau itself said it does not give those statistics out. According to the Wall Street Journal, there were 21 bias-related crimes so far this year on Staten Island versus nine over the same time period last year.

Crime overall is climbing on Staten Island. From mid-July to early August, the number of murders was up 150 percent and robbery is up 100 percent compared to the same time period in 2009. The increase is almost all within the 120th Precinct on the North Shore. Citywide the murder rate is up 3.4 percent and robberies 6.4 percent over the same time period.

Some of the spike in reported hate crimes may have to do with the public attention and official encouragement to report them. Maria Morales, who runs a taqueria in Port Richmond, told the Journal that she believes it is the reporting that is up, not the number of incidents.

Behind the Crimes

Some speculate the attacks are part of a gang initiation. Others call some of them “crimes of opportunity” -- when youthful offenders prey on Mexican day laborers coming home late at night with cash in their pockets. The explanations have not warmed the chilling effect of the crimes on the Mexican and gay communities on Staten Island.

Alejandro Galindo, 52, was attacked by four black men on June 24 while riding his bike home from his job as a dishwasher. He told the News that he could not explain the attack. His daughter, Blanca Galindo, told the paper, “He still lives in fear. They did not take anything. He was attacked just for being who he is.”

There is no doubt that the attack on Richard and Luis Viera, 13-year residents of Staten Island, at the Stapleton White Castle in July was unequivocally an anti-gay hate crime. As they ate very late one night, a group of teens came in and said to Luis: “What the fuck are you looking at, faggot?” and then hit him on the back of the head.

When the couple followed the attacker out to the parking lot, more than a dozen teens surrounded them. Luis was able to run back into the restaurant, but Richard was beaten, leaving him with multiple bruises and ongoing dizziness. (White Castle, whose employees did nothing to aid the men on the night of the attack, sent them a corporate letter offering them a free meal!)

Luis wrote in an e-mail that, other than the Hate Crimes Task Force, “no other police outreach ever made an attempt to assist us. On Staten Island the local police are very close-knit unit, and dealing with these issues and other ethnic issues is of the least importance to their daily work assignments. The mentality here on Staten Island is one of ignorance, which I was quite familiar with having grown up in a small town in Alabama during the '70s and 80s.”

A Night Out Against Hate

Staten Islanders are trying to fight back. Richard Veira was among those who participated in a march against hate crimes in early August. The march ended at the now-infamous White Castle.

While there, he said, “It’s not a gay cause. It’s a human issue. If I give in to fear, fear will win. I’ve got too much life to live.” He acknowledges that hate crimes don’t happen in a vacuum, citing the terrible economy and the lack of constructive outlets for these young people.

At 2 a.m. the night before this march, community members held a vigil at the White Castle to counter the idea that gay people would be cowed into not going out at night.

Jim Smith, who was the grand marshal of the first Staten Island gay pride parade in 2005 and grew up in West Brighton, said the gathering “was amazing. There were packs of young people in groups of 20 to 30 -- probably looking for trouble and most of them not old enough to drive.” He said that three young girls came over to offer support, but other youths reportedly taunted those keeping the vigil.

“Some people only feel powerful by putting other people down,” Smith said. “You can’t preach to them. It is hard to preach against hate.”

Ed Josey, 70, the president of the Staten Island chapter of the NAACP and an African American, said that the kids committing these crimes “are falling through the cracks.” He said when the crime in Port Richmond was just black-on-black, “there was not the police presence that you see now.” Still, this current wave of violence on Staten Island “is the worst that I can recall, but by and large people get along pretty well here. It’s a small element doing this.”

Josey was raised on the South Shore, had maybe three black classmates in high school “and never had a black teacher.” He said that the Staten Island Expressway was essentially a “Mason-Dixon line” on the island with few black people only allowed to the south of it. Today he says that the racial climate is far different. “There are far more interracial couples. The lines have fallen today. Progress has made things better.”

For more on civil rights related actions this summer, check out Action Taken on Bullying in Schools and No-Fault Divorce.

Andy Humm, a former member of the City Commission on Human Rights, has been in charge of the civil rights topic page since its inception in 2001. He is co-host of the weekly "Gay USA" on Manhattan Neighborhood Network (34 on Time-Warner; 107 on RCN) on Thursdays at 11 p.m.