Reimagine Education in New York – Without Segregation

(photo: Michael Appleton/Mayoral Photography Office)

Governor Andrew Cuomo has called rightly on New Yorkers, in the face of the COVID-19 pandemic, to reimagine education. We should reimagine it without racial segregation.

The novel coronavirus’ path of destruction has starkly illuminated the structural racism that underpins so much inequality in America. That inequality includes educational segregation in New York.

Structural racism, which is the historical and ongoing racial discrimination and segregation of Black people in particular, is typically instigated or sanctioned by government. It has created the unequal foundation for so many aspects of life, including widely documented, underlying health disparities for Black and Latino individuals. It has played a fundamental role in where we live (through federal redlining and other discriminatory practices) and, therefore, where our children attend school.

As a result of structural racism, New York is the most segregated state for African-American students, with 65 percent of African-American students in intensely segregated schools. That designation is heavily influenced by the New York City public school system, but the segregation is statewide. That segregation is often formally structured through the fragmentation of school districts.

Long Island’s two counties, for instance, have 125 school districts. Not surprisingly, Long Island is one of the 10 most segregated metro regions in the nation, and segregation is on the rise. According to ERASE Racism, in 2017, dramatically more Black and Latino students on Long Island attended segregated schools than 12 years earlier. New York City is also among the 10 most segregated metro regions, and its public schools are similarly highly segregated.

Yet distance learning, now a sudden reality, may have a valuable role to play in undermining segregation. It offers a vehicle for creating digital course offerings and other convenings that could free students from the entrenched landscape of racial isolation and inequity.

Through distance learning, students from multiple school districts could come together to learn and share experiences without being constrained by the geographic limitations imposed on them by previous generations and their prejudices. They might come together, for instance, for Advanced Placement courses or International Baccalaureate classes and broaden their understandings by sharing insights with students from other backgrounds.

They might also convene digitally for extracurricular activities. A model for that already exists with ERASE Racism’s Student Task Force, which consists of 23 high school students from 17 schools in Nassau and Suffolk counties on Long Island. While the Task Force previously met in person for most of its activities, we began meeting exclusively remotely in response to the pandemic. The Task Force and its thoughtful discussions, plans, and programs demonstrate the extraordinary benefits of students convening across school districts and even counties to learn together and from each other.

Implementing distance learning across school districts at a significant scale would require a more aggressive role by the State Education Department. The implementation of initial distance-learning initiatives amid the pandemic – with each school district acting in isolation, regardless of existing resources and capacity – merely reinforced the educational disparities already in place, as wealthier, whiter school districts were inevitably better able to implement those initiatives than poorer districts with more Black and Latino students.

Regardless of whether the decision to leave districts on their own was made deliberately or by default in the face of the looming pandemic, now is the time to prepare for enhanced educational outcomes in the new school year. Now is the time to think more creatively about options. That is where the opportunity for innovation emerges – both in how education can be advanced through distance learning, which is presumably here to stay to a degree still to be determined, and in diversifying educational instruction and environments in the process.

Three steps are key: First, the state should provide the needed funding to ensure that poor school districts can take advantage of online instruction, with enhanced tools and training to enable all teachers to deliver optimum instruction on distance-learning platforms. Second, the state should work with Internet providers to ensure that students in poor communities have Internet access affordably – even free. Third, the Board of Regents should ensure that every child has access to the equipment, connectivity, and instruction needed for effective utilization of distance learning.

In that context, New York should ensure that curricula are culturally responsive, reflecting the diversity of race, ethnicities, and cultures represented in our country and in New York state, even though they are not represented in all districts. Fortunately, the State Education Department has already developed a “Culturally Responsive-Sustaining Education Framework,” on which ERASE Racism provided feedback as it evolved.

The Framework helps educators create student-centered learning environments that affirm diverse identities, while preparing students for rigor and independent learning and elevating historically marginalized voices, among other goals. It addresses the reality that, in order to tackle racial disparities across the nation, it is necessary to have conversations in classrooms about the truth of structural racism throughout history and in the present day.

In reimagining education in New York, those same historically marginalized voices are stakeholders that need to be engaged: students, educators, parents, and community members. Those whose work and passion have focused on identifying and addressing the structural racism that has kept segregation in place must be fully involved, as their insights are vital to dismantling that persistent scourge. ERASE Racism stands ready to help in that endeavor.

Governor Cuomo has called on New Yorkers to reimagine education in the face of COVID-19. Now is the time to convert this public health and economic tragedy into a catalyst to destroy the perpetual plague of racial segregation and inequity.

***

Elaine Gross is president of the regional civil rights organization ERASE Racism. On Twitter @EraseRacism.

***

Have an op-ed idea or submission for Gotham Gazette? Email This email address is being protected from spambots. You need JavaScript enabled to view it.

NYCHA Tenant Leaders: Where Amazon Never Arrived, New Opportunity Arises

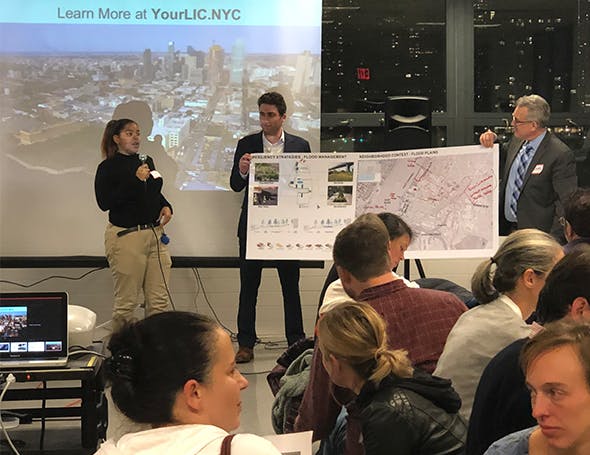

(photo: Your LIC)

The impact of the COVID-19 pandemic has not been equitable across New York City. While some New Yorkers have been able to work from home, or leave the city temporarily to wait the pandemic out, our NYCHA family has been devastated with the astounding loss of life and by an economic collapse at a scale we have never experienced before.

We have seen many people speak out about how to help NYCHA recover from this pandemic. On behalf of the nearly 17,000 residents of four Western Queens public housing developments, the virus has been catastrophic for our neighbors and the number one thing we will need coming out of this unprecedented time is jobs.

Thousands of our neighbors have lost their jobs and income, and we are ready to help New York City get back to work. NYCHA is the bedrock of Long Island City and the permanency of our homes provides an opportunity to access our residents for job opportunities. But we need the access, and we need to kickstart the creation of new opportunities to make up for the jobs that have been lost and may never return

We recently sat down with local Queens and citywide leaders in the workforce development community, convened by four developers (MAG Partners, Plaxall, Simon Baron Development, and TF Cornerstone) pursuing the Your LIC process to create a comprehensive plan for the Long Island City waterfront that is anchored with a strong jobs and commercial district.

We talked about an integrated, place-based workforce development plan that benefits the existing local workforce, including a community center that can connect all of Long Island City, flexible job training, pathways for high school students to find internships, services including childcare for families, and opportunities to strengthen soft skills.

It was uplifting to hear from our neighbors – non-profits, real estate stakeholders, workforce training experts, and residents – who have come together to begin to figure out real solutions to bounce back from this crisis and to build a future of opportunity.

Of course, we’re no stranger to fighting for the future of our community. Leading up to Amazon’s decision to pull their plans for ‘HQ2,’ we were making progress to ensure that the deal would work for all of us. This neighborhood was prepared to receive a job-training center, the launch of a workforce development program with LaGuardia Community College, modern after-school programs, and internships for our children.

For months following Amazon’s decision to pull out, we felt forgotten and it appeared that our goal of creating a Long Island City waterfront that would empower our community and create a significant number of jobs was lost.

Then last year, a new process emerged. The proponents of this new project began organizing a series of public engagements to hear firsthand what Long Island City residents want to see along the waterfront. Since the very beginning of the process, NYCHA residents have had a seat at the table, with hundreds from the community participating in the public workshops and online discussions. Our voices are finally being heard and we are continuing to meet with members of the Your LIC team to make sure that the proposal is one that works for all of us.

Since the first workshop in November of last year, we have discussed the importance of economic empowerment in workforce development, resiliency, and creating connected public open space, and schools, places for the arts, and other community spaces.

We know that the buildings proposed on the waterfront may be tall and dense, and some people will have concerns about that, but we’ve been seeing towers rise in Long Island City for a long time. In those developments, residents come and go, but the residents in NYCHA developments in Western Queens are permanent, and it’s time for a proposal that benefits and draws from the human capital in our communities.

The need to deliver jobs – here in Western Queens – and community benefits are more critical than ever for the future of this place. These are the types of tools and investments that make a real difference in people’s lives and will do so for our children, too.

As we look forward to planning for the future of the Long Island City waterfront – and toward the future of our city as a whole – we can’t afford to squander yet another opportunity to create jobs and to deliver progress right here in a community that both needs it and deserves it.

When crises hit New York City, so many turn to NYCHA to lament how public housing residents are disproportionately impacted, but when given the opportunity too little action is taken. This is our community. Please don’t forget us once again. Support us as we build a strong future for NYCHA and our neighbors.

***

Carol Wilkins is the president of the Ravenswood tenants association; April Simpson-Taylor is the president of the Queensbridge tenants association; Claudia Coger is president of the Astoria Houses tenants association; and Annie Cotton-Morris is the president of the Woodside Houses tenants association.

***

Have an op-ed idea or submission for Gotham Gazette? Email This email address is being protected from spambots. You need JavaScript enabled to view it.

City Budget Crisis Threatens Lifeline for Day Laborers and Immigrant Workers

NICE staff and volunteers deliver groceries to workers impacted by COVID-19

“The rags were so filthy, and we had no soap and little water to clean them, so we felt like we were spreading the virus in the subway car by our cleaning…We started on Monday, but they did not give us masks ‘til Wednesday…The gloves they gave us were for making sandwiches, not for cleaning! They would break, and there were no more, so we brought our own…I worry: How many people will get sick because these cars were “cleaned” this way?”

-Susanna, a New Immigrant Community Empowerment (NICE) respondent reporting unsafe working conditions and fearing other New Yorkers would get sick in ineffectively-cleaned subways cars.

Susanna worked cleaning subway cars to keep essential workers and all New Yorkers safe during the near-lockdown and as the city “reopens,” but the contractor was cutting corners and putting profit over the health of workers and the public. With NICE’s support, Susanna protested her sub-prevailing wage pay, and what she saw as unsafe working conditions that ineffectively cleaned subways and posed risks to all New Yorkers.

Susanna’s voice is one the New York City Council should hear as Council members decide how to distribute discretionary funding. Many immigrant-led/serving nonprofits that have been critical lifelines for immigrant workers are at risk of losing their funding due to the city budget crisis. This would be tragic for the organizations, immigrant workers and families they serve.

Thankfully, the City Council can make these New Yorkers a priority as negotiations proceed leading up to a new budget by July 1.

Research by New Immigrant Community Empowerment (NICE) -- a nonprofit that supports day laborers and other low-wage immigrant workers and their families through its Worker Centers in Queens, Brooklyn, and the Bronx -- shows how these communities are extremely hard hit by the pandemic. Survey data are grim: the pandemic sharply increases NICE families’ risk of poverty and homelessness.

Only 20.5% had worked at all during the pandemic; 90% had not worked in over four weeks. As a result, 41% of respondents reported being at risk of losing their housing, and 32% feared they could be at risk. Those at risk lived with an average of 2.2 children, nearly all U.S. citizens. Research shows homeless children face a “cascade” of preventable harms making it harder to learn and thrive as adults. NICE’s data point to a developing crisis we can still act to prevent.

Moreover, of those surveyed, 36% reported COVID-19 symptoms (loss of taste/smell, cough, difficulty breathing). Actual infection rates could be higher, because infection precedes symptoms. Equally worrisome: 41% reported underlying conditions (eg asthma) that can worsen covid’s morbidity. Finally, 15% reported “acute anxiety, depression, or suicidal thoughts as a consequence of Covid19.”

NICE’s strategic thinking is to respond over what the Centers for Disease Control call the “lifecycle” of the pandemic, which will likely include the immediate crisis; phased reopening by work sector, including construction work; possible COVID-19 case upticks, and re-shutdowns; development and broad use of better treatments and a vaccine; and transition out of the pandemic.

Efforts like these will be essential in each pandemic lifecycle stage. First, NICE members work mostly in construction, one of the first large industries in New York City’s phase 1 "reopening." The research NICE has done (and seeks to continue) could offer real-time data on upticks – the canary in the coalmine – for policy-makers. Faster response can save thousands of New Yorkers’ lives. Second, NICE and similarly-situated organizations are directly linked to the most vulnerable New Yorkers who are unlikely to be contacted by or respond to most polling or online surveys on the coronavirus (including the CUNY School of Public Health’s well-designed weekly 1,000-person survey on COVID-19 impacts). Third, immigrants’ deep trust in their organizations makes them essential partners as we move through the pandemic lifecycle. These organizations can help ensure all New Yorkers have fair access to a vaccine, once we have one. But they must survive financially to do this work, which City Council funding can help ensure.

Finally, including funding in the New York City budget for organizations that support immigrant workers will keep all New Yorkers safe now and in the long-run. Consider Singapore, which nearly quashed the pandemic, but neglected its immigrant workers, causing COVID-19 cases to rebound. Just as Susanna worried about people who could get sick from a badly-cleaned subway car, all New Yorkers should want Susanna to have proper gloves and masks, and want the construction workers, nannies, and deli workers who are part of the fabric of New York life to be as protected as most everyone else. New York is a resilient place, but must also be a just and smart place, where it protects all New Yorkers equally, so we can all live safely and well.

***

Manuel Castro is the Executive Director of New Immigrant Community Empowerment (NICE). On Twitter @NICE4Workers. Robert C. Smith is a Professor in the Marxe School at Baruch College and the Sociology Department, Graduate Center, CUNY, and co-author of Immigration and Strategic Public Health Communication (2019, Routledge).

***

Have an op-ed idea or submission for Gotham Gazette? Email This email address is being protected from spambots. You need JavaScript enabled to view it.

Why New York City Must Put Educators and Counselors, Not Cops, in Charge of School Discipline

Mayor de Blasio gives remarks on school safety (photo: Rob Bennett/Mayor's Office)

Amid protests spurred by the police killing of George Floyd, activists from Minneapolis to Chicago to New York City are pushing to reduce the presence of police in schools, and a number of school districts are heeding their call. Most recently, New York City Council Members Mark Treyger and Donovan Richards are proposing to end the ties between the New York Police Department and Department of Education.

They have a point. Reducing the number of cops in schools need not diminish safety. However, with 25 of the nation’s largest school districts now outsourcing at least some school safety to police departments, severing those ties will require the development of new methods for de-escalating conflict. Districts will need to learn from successful experiments that engage students, teachers, and administrators in improving school culture in ways that promote both safety and learning.

The call to reduce police presence in schools follows a decades-long escalation. In the 1990s an increase in gun violence in schools led President Bill Clinton to sign The Gun Free Schools Act, which made zero-tolerance school discipline a national movement. The law initially mandated punishments for firearms possession—mandates that were later expanded to include a range of crimes and infractions.

By 1998, in the first takeover of its kind, then-Mayor Rudy Giuliani arranged for the New York police department to take command of the education department’s Division of School Safety; he did so over the objections of at least two schools chancellors. New York City has had more than 5,000 police personnel assigned to schools in recent years, equivalent to one of the largest police forces in the country; by contrast, the combined number of school counselors and social workers was less than 4,300 in 2019.

Following the shooting at Columbine High School, in Colorado in 1999, the police presence on school campuses nationwide grew steadily with so-called School Resource Officers typically hired, and paid, by local police departments.

Violent crime and thefts in schools declined 70 percent between 1992 and 2013 even as some high schools reported an increase in discipline problems after police appeared on campus. Indeed, schools with officers reported five times the number of arrests for "disorderly conduct" as schools without them. A lack of training in “positive behavioral interventions” has led many schools to become “overly reliant” on harsh discipline and to criminalize infractions that, in the past, might have merited a scolding from the principal, according to a recent Clemson University study.

The increased police presence and zero-tolerance policies have had a particularly adverse impact on students of color. Despite efforts under the Obama administration to limit the role of police in school disciplinary matters, students of color have been targeted for suspension and arrest in large numbers nationwide. Although suspensions have declined in recent years, overall arrests have increased; Black students, who make up just 15.5 percent of all public school students, accounted for over one-third of all school arrests, according to a 2018 government study, which found that “implicit bias” was partly to blame for the increase. Black boys are arrested three times more often, and Black girls 1.5 times more often, than white boys.

In New York City, overall suspension rates declined by 39.4 percent in the decade leading up to the 2016-17 school year. While the suspension rate of Black middle- and high-school students also declined during that period, it remained 2.8 times higher than that of white students.

At the same time, the presence of metal detectors, security cameras, and security guards makes kids of color feel less safe in school “physically and psychologically,” according to the National Association of School Psychologists, which can, in turn, have a detrimental impact on students’ ability to learn. (Nor is there clear evidence that the use of such restrictive security equipment is “effective in preventing school violence,” according to the study.)

By contrast, research has shown a strong positive connection between nurturing school environments and learning. A recent study of high-poverty New York City schools, which looked at the impact of neighborhood violence on standardized test scores, found that the performance of students exposed to violence suffered if they attend schools with weak climates; by contrast students who attend schools perceived as both safe and “having the strongest sense of community,” suffered no reduction in test scores even if they were exposed to violence.

Creating the kinds of nurturing environments associated with both safe schools and better education outcomes requires an all-hands-on-deck approach. Schools need to foster new methods, such as peer-mediation and behavior-management strategies that deescalate conflict and put educators—not police officers—in charge of the vast majority of discipline infractions.

Take the case of the Bayard Rustin complex of six small schools in New York City, which, in 2017, began petitioning both the education and police departments to suspend unannounced metal-detector screenings at the school building, where 96 percent of students are people of color. The screenings were conducted by the NYPD even though discipline problems in the building “are rare” and the school principals opposed them—more than 80 percent of students said they felt safe in the school building, according to education department surveys. The New York Civil Liberties Union was brought in to mediate a discussion among the schools and the education and police departments. In 2019, when the NYPD was expected to install permanent metal detectors, the students finally won a partial victory; while Bayard Rustin remained a random-screening site, permanent metal detectors were never installed.

The battle at Bayard Rustin—and the students’ modest success in keeping out permanent metal detectors—was a school culture and curriculum that encouraged students to grapple with real-world problems. The Bayard Rustin complex is run collaboratively with educators at all six schools jointly determining the use of common spaces and policies. Three schools are members of the highly-regarded New York State Performance Standards Consortium, which allows students to complete in-depth, long-term projects, often tailored around student interests, in lieu of most standardized tests.

The fight against metal detectors was led by Bayard Rustin students with the support of educators. Brady Smith, principal of James Baldwin, a “transfer” high school for over-age, under-credited students who struggled at previous schools, and a member of both the performance standards consortium and the progressive NYC Outward Bound network, persuaded his fellow principals to appoint a student advisory council to address the metal-detector problem. He also insisted that the student council include some “marginalized students,” noting: “A lot of schools create pathways for student leadership that appeal to a particular type of student—the extrovert, charismatic student.” For this committee, he wanted the kind of students who would focus on “issues,” rather than having “good events.”

Similar efforts to engage students in critical problem-solving have borne fruit elsewhere. In Leander, TX, a large district outside Austin, a years-long, student-led anti-bullying campaign has not only mitigated a major problem at district schools, but created leadership opportunities for teens. The effort, fostered by teachers and administrators, grew out of a nearly four-decade commitment to a school-improvement philosophy that encourages problem-solving at all levels of the school—from students to administrators.

Despite a growing movement to cut police budgets, too many officials still view the police as a school safety panacea. Although crime in New York City schools is at record lows, Mayor Bill de Blasio has increased the school-safety budget by 25 percent since taking office in 2014. He has also called for a 1.36 percent increase, to $427332 million, in spending on school safety officers next fiscal year, even as he plans to cut $827 million from the education department and prepares to borrow $7 billion to make up for shortfalls in the city’s operating budget.

Getting cops out of schools will present both opportunities and challenges, especially in mitigating the kind of childhood trauma that often leads to school violence and discipline problems. As of 2017, nearly 29 percent of the school incidents in New York City involving police or safety agents involved a “child in crisis,” and resulted in the child being taken to a hospital for a psychological evaluation; by contrast, only 12 percent of the incidents resulted in an arrest.

For the transition to be successful, the education department will need to retrain school safety officers, especially in so-called restorative justice practices that include addressing sources of friction before they escalate, and working with both victims and the accused to develop long-term solutions, and to “foster understanding” and “impose fair punishment.” And as principals take charge of supervising school safety, the department may also need to reduce some administrative burdens now shouldered by school administrators.

In the aftermath of the Covid-19 pandemic, students who have spent months under lockdown have suffered increased depression and anxiety that can impede learning—the kind of trauma that most benefits from mediation by educators and counselors, and not police.

***

Andrea Gabor is Bloomberg Chair of Business Journalism at Baruch College/CUNY and author of After the Education Wars (The New Press, June 2018). On Twitter @aagabor.

***

Have an op-ed idea or submission for Gotham Gazette? Email This email address is being protected from spambots. You need JavaScript enabled to view it.

Pride and Ending the HIV Epidemic in New York This Year

June is Pride month (photo: Michael Appleton/Mayoral Photography Office)

Octavia Leona Kohner is a former sex worker and a survivor of sexual assault. As a woman of transgender experience, she’s 49 times more likely than the general population to be HIV positive. But Octavia is HIV negative. She’s an example of the tremendous progress we’ve made in our effort to end the HIV/AIDS epidemic in New York State -- an epidemic that has disproportionately impacted the LGBTQ community and communities of color.

Six years ago, New York set out to end HIV by 2020, and thanks to Governor Cuomo’s leadership, we are on the verge of becoming the first state in the country to do so, 10 years before the national goal of ending the epidemic by 2030. The most recent data from the New York City Department of Health and Mental Hygiene shows that in the first half of 2019, 876 New Yorkers were newly diagnosed with HIV, down from 984 for the same time period the previous year. That’s progress we can be proud of, and Pride month is a time to celebrate our successes. But there is still more work to do.

As with COVID-19, communities of color are the hardest hit by HIV. Institutional racism and social, economic, and educational inequities lead to stark health disparities. In the first half of 2019, Black (45.8%) and Latino (37.4%) people still represent a disproportionate share of new diagnoses in New York City. And transgender people were one of the only groups to see a slight increase in new HIV diagnoses in New York City from 2017 to 2018. Most new diagnoses come from zip codes with above average levels of poverty.

The HIV and COVID-19 crises reaffirm the vital importance of fighting for health-care access, racial justice, and health equity. For example, pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP) is a medication that is 99% effective in preventing HIV transmission, yet it isn’t reaching many who need it most. Medicaid Special Needs Health Plans are specifically designed to provide care to people who live with or are placed at elevated risk for HIV. Octavia is a member of Amida Care, New York’s largest Special Needs Health Plan, which connects HIV-negative members like Octavia to PrEP.

When Octavia started on PrEP, she spoke with an Amida Care pharmacist who helped dispel misinformation about the treatment and answer her questions. Some trans people fear that PrEP may interfere with or interact poorly with their hormone therapy, so having a trusted, readily available resource for accurate information is critical. Amida Care’s pharmacy team follows up regularly with Octavia to make sure she’s adhering to her treatment and responding well. She has also accessed mental health services through Amida Care.

Amida Care works closely with members to create personalized care plans based on each individual’s unique needs, connect them with culturally competent providers, and support them to stay in care and take their medications. Amida Care’s Live Your Life wellness program gives members access to free events to feel good in their own body.

Thanks to medical advancements, HIV can now be treated with just one pill a day, but many people living with HIV today are taking additional medication to manage other chronic conditions including hypertension, diabetes, depression, and addiction. Special Needs Health Plans like Amida Care provide wraparound care to ensure members get the medications they are prescribed and adhere to their personalized care plan. Amida Care also checks that there are no adverse side effects or potentially bad interactions of multiple prescribed medications, and helps to streamline administrative processes for providers.

Pharmacy care management is critical to improving health outcomes, avoiding costly hospitalizations and reducing the number of new HIV diagnoses. As a result, many people living with HIV have become healthier and virally suppressed, which means they are unable to sexually transmit HIV to others. The viral load suppression rate among Amida Care members in 2005 was 60% -- today it’s 80%.

Octavia has not only remained HIV negative, but she works to encourage others to consider PrEP and take control of their sexual health. She’s found a community that supports her in living her most authentic life, and she works to support others as a gender and sexuality consultant.

We have made great progress toward reaching our goal of ending the HIV epidemic in New York. Special Needs Health Plans will continue to do our part - through the end of 2020 and beyond - by working in the hardest hit communities and improving health outcomes for all.

***

Doug Wirth is the President and CEO of Amida Care. On Twitter @AmidaCareNY.

***

Have an op-ed idea or submission for Gotham Gazette? Email This email address is being protected from spambots. You need JavaScript enabled to view it.

Ensuring the COVID-19 Response Prioritizes the Needs of Vulnerable New Yorkers

Front-line workers (photo: Michael Appleton/Mayoral Photography Office)

The COVID-19 crisis has laid bare the fragility of our region. It has compromised our physical and mental health, caused unprecedented disruption to our economy, and created a deep uncertainty about our future.

Across the state, the pandemic has revealed how inequitably our communities are prepared to cope with an emergency of this magnitude. The Department of Health in New York City released data reflecting an alarming nationwide trend: vulnerable groups such as low-income individuals, senior citizens, and people of color are suffering from COVID-19 at disproportionate rates.

This is due not only to unequal access to health care, but also to an intersecting web of social disadvantages that form the most pervasive preconditions for any disease. Food insecurity, poverty, and housing instability are felt most acutely in the communities where the COVID-19 outbreak has struck the hardest.

As we consider the long road to recovery from this crisis, one thing is certain: we have an obligation to close the health-care gap in our state and create the conditions for a system that works better for all New Yorkers.

Preventing this kind of pandemic in the future will require a response beyond a vaccine. We must make holistic investments to address the full spectrum of health care and health-related requirements facing our most vulnerable.

What can be done?

The good news is that this crisis has revealed our capacity to help those in need.

Hundreds of organizations across our state are dedicated to serving the diverse, health, and health-related essentials of vulnerable New Yorkers. These health-care providers, nonprofits, and community groups represent a broad coalition addressing the full scope of the need throughout our state. They require our support now more than ever.

As New York's largest health-care foundation, we at the Mother Cabrini Health Foundation are in a unique position to provide ongoing support to community-based initiatives that keep people safe and fed, help them return to work, and support healthy lifestyles.

On March 31, 131 years to the day Mother Frances Xavier Cabrini arrived in New York City and rolled up her sleeves to care for the poorest New Yorkers, we announced $50 million in emergency grants to address the many health-related needs of New Yorkers as a result of the COVID-19 pandemic.

In early May we issued our first round of emergency funding, nearly half of the $50 million allocation. We supported programs and workers at more than 100 organizations who, like our namesake, have rolled up their sleeves to provide immediate, essential services: personal protective equipment for health-care and social-service workers, emergency supplies at food banks and pantries, and hazard and/or overtime pay to frontline, direct-service health-care workers.

These organizations include the Food Bank of Central New York, Home Care Association of New York State, Catholic Charities Brooklyn Queens, JASA, Citymeals on Wheels, Iroquois Healthcare Association Inc., Circulo de la Hispanidad, Mental Health Associates of Franklin County, and the Greater New York Hospital Foundation.

Their efforts are saving lives.

As we begin the long recovery from COVID-19, we can also help save lives by supporting policies and programs across New York State that address the broader factors that exacerbated this public health crisis, especially among lower-income communities, communities of color, and elderly populations.

Looking to our soon-to-be-announced second round of emergency funding, the Mother Cabrini Health Foundation knows that health care is the sum of many factors. Our mandate has never been more urgent.

Moments of crisis don’t only beget immediate danger; they also offer long-term opportunity.

Ours now is to take decisive action to create a more equitable healthcare landscape. We must ensure that the most vulnerable and fragile among us aren’t forced to bear the brunt of the next crisis, and that all New Yorkers can enjoy healthier, more prosperous lives.

A small nun, Mother Cabrini left a large legacy. She and her sisters addressed immediate needs by standing in the backs of churches to hand out food, clothing, and supplies to families living in poverty. Beyond this, she had an expansive vision that included the founding of schools and orphanages to prepare the vulnerable to survive in a system that would not always catch them were they to fall.

We honor Mother Cabrini's legacy when we put into practice what she has taught by supporting both immediate and broader health needs through nutrition, housing, education, and employment programs that will outlive this deadly virus for generations to come.

***

Msgr. Gregory Mustaciuolo is Chief Executive Officer of the Mother Cabrini Health Foundation, a private, nonprofit organization based in New York City and supporting programs throughout New York State. On Twitter @cabrinihealthNY.

***

Have an op-ed idea or submission for Gotham Gazette? Email This email address is being protected from spambots. You need JavaScript enabled to view it.

Staving Off an Eviction Nightmare by Expanding New Yorkers' Right to Counsel

An eviction nightmare looms as housing court reopens (Benjamin Kanter/Mayoral Photo Office)

A new threat is looming for the very Black and brown communities in New York City that have been hit the hardest by the dual pandemics of coronavirus and racism in policy: a massive wave of evictions.

That’s because phase 1 of New York “reopening” didn’t just apply to construction and curbside retail. It also applied to housing courts. This could have disastrous consequences for tenants. Housing court personnel have already started reporting back to their workplaces. This Monday the courts are scheduled to begin hearing eviction proceedings again. We join tenants rights activists in urgently calling for this date to be pushed back.

We also need to act now to prevent an avalanche of evictions no matter when housing court cases resume. We can do that by smartly leveraging the landmark law that established right to counsel in New York City.

Eviction cases that were suspended before the pandemic will be resumed, and there likely will be an onslaught of new cases -- the gubernatorial order pushing back evictions to August 20 does little to stop landlords from filing for new evictions.

The reopening of housing courts will also create a massive public health problem. New York City’s housing courts on a normal day are incredibly overcrowded, with tenants, lawyers, and staff crammed into hallways, waiting areas, and small courtrooms. Pre-covid, there were 2,000 people in the Bronx housing court alone, every day. Anything like a normal docket of cases will make it impossible to keep safe social distancing -- and we know that coronavirus spreads most easily in crowded, indoor settings.

There is a simple way to prevent both the massive wave of evictions and unsafe conditions in housing courts: only allow eviction cases to proceed if tenants have access to a lawyer.

In 2017 New York City enacted a landmark, first-in-the-nation law establishing right to counsel for low-income tenants facing eviction. The law is being phased in zip code-by-zip code over five years, but has already dramatically increased the portion of tenants citywide with representation, from less than 5% to now approximately 30%. It’s proven to be spectacularly successful: 84% of tenants receiving legal representation have been able to remain in their homes. No surprise that cities around the nation are enacting policies based on New York City’s example.

Now we need to head off the looming eviction crisis by immediately taking right to counsel citywide -- to every zip code. We are drafting legislation now to put this into effect immediately.

Recognizing that we are in a financial crisis, this could be done in a revenue neutral way, by simply altering existing contracts with legal providers to spread their attorneys out over all zip codes.

New York City’s housing courts have routinely adjourned cases so tenants can secure representation. In fact, after right to counsel was implemented, a Bronx judge even cancelled a judgment against a tenant because they weren’t provided a lawyer.

So if tenants in all zip codes have a right to counsel, this will slow the daily volume of cases that can move forward in accordance with the number of right to counsel attorneys available -- in practice significantly slowing the pace of evictions.

The substantial reduction in the number of people in courts will also be a win for public health, since it will make room to implement social distancing policies that otherwise would be impossible.

Over the longer-term we need to expand the scope of New York City’s right to counsel law, including through legislation we have sponsored that would raise the income cutoff. This will be critical to achieving a fair recovery for our city in the years ahead.

But right now we need to take action fast to head off a crisis that would inflict additional pain on the low-income New Yorkers who have already suffered so much during the pandemic.

Right to counsel for tenants has already proven to bring more justice to housing court. Now it can be a powerful tool to ensure health, safety, and stability at this time of unprecedented crisis.

***

City Council Members Mark Levine and Vanessa L. Gibson represent parts of Manhattan and the Bronx, respectively, and co-sponsored the city’s landmark right to counsel law. On Twitter @MarkeLevineNYC and @Vanessalgibson.

***

Have an op-ed idea or submission for Gotham Gazette? Email This email address is being protected from spambots. You need JavaScript enabled to view it.

Informal Recyclers are Essential to a Just and Green NYC; Here's 7 Things We Must Do To Help Them Survive

Canners redeeming their work (photo: Carlos Rivea for Sure We Can)

In New York City, there are an estimated 8,000 informal canners, or people who collect, sort, and redeem deposit-based containers for a living. Earning a nickel per can or bottle, canners straddle a liminal space in society: though often visible pushing carts with bulging bags through the city, they work in the shadows because of fear of harassment, shame, and a lack of public support.

Canners are indispensable to New York State’s environmental sustainability efforts and to the local economy. Each year, more than 5 billion containers are redeemed in New York, generating over $400 million for the economy and funding environmental campaigns.

Canners play an important role in achieving these results. For example, the 800-plus canners who frequent Sure We Can, the only not-for-profit redemption center in the five boroughs, redeemed 12 million deposit-based containers and returned over $700,000 to the local community last year alone. Further, Sure We Can supports eight green jobs and educates hundreds of K-12 and college students about urban environmental and social issues.

However, the COVID-19 pandemic has been disastrous for informal workers like canners. The current crisis exacerbates long-standing systemic economic, social, and environmental inequities and poses numerous public health risks to canners. Bottle redemption is considered an “essential service,” but economic support and social protections are not extended to canners. Many Asian-American canners have reported increased harassment and stigmatization. And in economic downturns, when unemployment swells, the number of people who turn to canning to survive increases.

Today, supporting canners is more important than ever. Here are several short- and long-term actions you can take to help canners and grow a green and just economy as we rebuild from the COVID-19 crisis:

Acknowledge and thank canners in your neighborhood for the services they provide. Canners are our neighbors: they often collect containers near their homes, cleaning up the neighborhood in the process.

Separate redeemable containers from other plastic, glass, and aluminum containers, and set them aside in a clear or marked bag for canners. If you live in a large apartment building, ask the maintenance staff to aggregate redeemable containers for canners.

Offer clean, unused, and sealed personal protective equipment (PPE), including gloves, face masks, and alcohol gel, to canners. Canners work independently and may not have access to PPE.

Advocate for economic relief measures for all informal workers, regardless of their tax-filing status. Support local organizations that are dispensing relief funds to those most impacted by the crisis.

Support the “Community Organics and Recycling Empowerment (CORE) Act” introduced by City Council Members Keith Powers and Antonio Reynoso. The CORE Act proposes the creation of community drop-off sites for the collection of organic waste and electronic waste, which currently contaminates the recycling stream and is hazardous to canners. Further, the CORE Act will create hundreds of green jobs.

Advocate for canners and informal workers to be included in decision-making processes across all levels of government. In cities around the world, the integration of canners into municipal solid waste management systems yields abundant social, economic, and environmental benefits.

Support legislation to increase the redemption value from 5-cents to 10-cents per container and to expand the type of containers eligible for redemption. Similar changes in Oregon have pushed recycling rates to over 90%. Further, updating the New York State “Bottle Bill,” which has remained largely unchanged since 1982, will provide canners a fair wage reflective of the value of their services.

As New York City enters phase 2 of “reopening,” canners should no longer be relegated to the shadows. We must recognize, advocate for, and advance the positive economic and environmental contributions of canners so as to realize the just and green New York City we all want.

***

Chris Hartmann, PhD, is an Assistant Professor of Public Health at SUNY Old Westbury and a board member of Sure We Can. Christine Hegel, PhD, is an Associate Professor of Anthropology at Western Connecticut State University and a board member of Sure We Can. Chicago Crosby is a canner and board member of Sure We Can. Josefa Marin is a canner and board member of Sure We Can. On Twitter @SureWeCanNYC.

***

Have an op-ed idea or submission for Gotham Gazette? Email This email address is being protected from spambots. You need JavaScript enabled to view it.

Who Traffic Enforcement Agents Really Are, and Why They Must Remain Part of the NYPD

Traffic Enforcement Agents take a knee

On Thursday, June 11, hundreds of New York City Traffic Enforcement Agents and Supervisors stopped work for eight minutes and 46 seconds to commemorate the tragic murder of George Floyd in Minneapolis. Employed by the NYPD, these members of the Communications Workers of America (CWA) were participating in a nationwide CWA job action to support the massive protests sweeping the country on behalf of racial justice and an end to police violence.

Is it surprising that these NYPD employees staged a job action for racial justice? If you knew who they were, it wouldn’t be. CWA represents approximately 2,800 agents and 400 supervisors who work in New York City Traffic Enforcement. Over 95% of them are people of color—primarily immigrants from Bangladesh and Africa, and Latinos and African-Americans. Traffic agents are extremely low-paid: their salaries start at just over $41,000 and top out at $50,000 after 10 years on the job. What’s worse, on average, 100 agents each year are physically assaulted by members of the public angered by a parking ticket or a disagreement at an intersection. The verbal insults—many of them racial slurs—are too numerous to count.

That is why it is especially disappointing to see these workers targeted, even inadvertently, by the leaders of two organizations we normally consider allies, in a recent column in this publication advocating the removal of traffic enforcement from the NYPD.

The recent Black Lives Matter protests have sparked an enormous grassroots demand for fundamental reform of the police department, a stance supported by the CWA. But moving Traffic Enforcement out of the NYPD is not meaningful reform—it is merely cosmetic budget-shifting in the name of reform. And such a move would utterly ignore the deeply felt concerns of the 3,200, overwhelmingly of-color workers who would be directly affected.

The authors raise serious concerns about the discriminatory impact of policing practices on Black and brown pedestrians and drivers—practices that CWA and the Traffic Enforcement Agents vehemently oppose. But these issues literally have nothing to do with the TEAs and Supervisors. To list just a few of the misleading arguments:

The authors decry racially discriminatory policing of social distancing during the pandemic, but traffic agents have had no authority to police social distancing.

The authors state that Black and brown New Yorkers receive 89% of the tickets issued for jaywalking or mid-street illegal crossing, but traffic agents have no authority to police jaywalking and never issue tickets for that offense.

The authors cite figures showing that Black and brown drivers are far more frequently pulled over by police and even more frequently searched for drugs and alcohol, but TEAs have no authority to pull cars over.

The bottom line is that CWA-represented Agents and Supervisors are only authorized to issue parking tickets and direct traffic in busy intersections. The only moving violations they ever issue occur when drivers “block the box.” Somewhat ironically, they do issue tickets to drivers who park illegally in dedicated bike lanes, something that Transportation Alternatives supporters surely appreciate.

Why, then, do our members care so deeply about remaining in the NYPD? The answer is simple: they believe the uniform provides a measure of safety. Directing traffic and writing tickets earns these agents no love or affection from most New Yorkers. When the traffic bureau was part of the Department of Transportation, agents were routinely derided as “Brownies.” Assaults—literally physical attacks in which faces were punched and limbs were broken —peaked in the early ‘90s at around 600 per year, a trend exacerbated by the late-1980s scandal in the Parking Violations Bureau. The agents fought for years to achieve "uniform status" in order to gain a measure of respect and security. They deeply believe that if they return to the Department of Transportation, disrespect from the public will increase and the assaults and racial slurs will escalate dramatically.

CWA and the Traffic Enforcement Agents and Supervisors support genuine reform of the NYPD. We want to see an end to the now-endless litany of young Black men who have suffered at the hands of police across the country. But moving traffic out of the NYPD satisfies only one need—the claim of a big reduction in the NYPD budget—and actually changes nothing. And there are 3,200 women and men, mostly of-color, who will be deeply hurt if such a change goes through. We urge the City Council and the Mayor to reject this idea.

***

Bob Master is Assistant to the Vice President of CWA District One and Rebecca Greene is a Traffic Enforcement Supervisor and Member of CWA Local 1181. On Twitter @cwabobmaster.

***

Have an op-ed idea or submission for Gotham Gazette? Email This email address is being protected from spambots. You need JavaScript enabled to view it.

Learning the Right Health-Care Lessons from the Covid Crisis

Health care lessons from the coronavirus crisis (photo: Kevin P. Coughlin/Governor's Office)

The saying “a crisis is a terrible thing to waste” is cliché, but true. Out of the coronavirus pandemic can come positive change, but we must learn the right lessons. At the peak of the COVID-19 crisis in New York some hospitals were overwhelmed – short of personnel, ICU beds, ventilators and PPE. But that does not mean, as some have argued, that more permanent hospital beds are needed.

To draw that conclusion and act upon it would be an extremely costly mistake that doesn’t address the real challenges facing New York’s health-care system. What is needed is an acceleration of the transition from a system of hospital-based ‘sick care’ to one of community-based health promotion and care.

While this state has the most expensive Medicaid costs in the country, we have mediocre results in prevention and treatment, according to the Commonwealth Fund Scorecard. We focus on costly hospital beds and services that are accessible and satisfactory (except for their high cost) to those with higher incomes, but underinvest in the primary care networks and population health initiatives that could give us a truly coordinated health-care system that prevents and manages illness and reduces the need for hospital care.

New York State has a total of about 21,200 hospital beds, or 2.5 per 1,000 people, down substantially (approximately 23%) over the past 15 years. The number of patient discharges (a measure of the number of people hospitalized) and length of hospital stays has also declined. Meanwhile, the number of ambulatory care facilities such as school- and hospital-based clinics has tripled. These would all seem to be good trends that indicate people are getting more outpatient care and needing hospitalization less.

But the number of pregnant women who receive no prenatal care and the number of New Yorkers without a primary care doctor have remained relatively unchanged, hovering at about 10 percent and just below 20 percent, respectively. And the number of emergency room visits per year had increased to almost 400 per 1,000 residents, 120% of the number in 2005, before the pandemic hit.

The COVID-19 crisis has been particularly acute in primarily poor neighborhoods and communities of color, where hypertension, diabetes, and other chronic illnesses are most prevalent. Investing in more and better health care in these neighborhoods will contribute to longer and safer lives. Much more attention is needed to treating people near where they live and creating trust in and reliance upon local clinics, nutritious food options, and behavioral health services so that visits to emergency rooms are not the first contact with the health-care system. This is where we should put our focus and funding, not on keeping thousands of costly beds open in case of severe emergency.

But that doesn’t mean we don’t also need to make changes in order to better respond to the next viral or other health crisis. In New York we operate our health-care system through separate silos of services: a hospital bed silo, a behavioral care silo, a nursing home silo, and multiple ambulance services. Moreover, many entities within each silo compete with each other for patients. In an emergency, all of these distinct organizational structures should be prepared to operate as if they were one, managing capacity intelligently. This means the state Department of Health must be placed clearly in command of all health-care facilities and providers, notwithstanding resistance that can be expected from some in the industry.

At the first recognition of the pandemic the state should have been able to put into operation a plan designed well in advance and tested once a year to ensure all aspects of the health-care system know their roles and could immediately function in a coordinated fashion. The system should have been organized by region, each with an agreed upon lead with hospitals, clinics, doctors, offices, EMTs, and ambulances working together. Two or three hospitals per region should be established as first receivers so ambulances, doctors, and clinics know where to send patients.

PPE would be distributed across the system and if and when a virus spreads hospitals could be added as receivers, staggered to account for discharges. Additional bed capacity can be added in existing and temporary facilities if needed, as occurred at the height of the covid crisis. Long-term care facilities would be incorporated into the emergency system. Outpatient clinics would be required to extend hours. Such a plan requires leadership and execution at the state level, so that when the red light goes on all the players understand they belong to the community effort.

More beds in an uncoordinated system will cost money on an ongoing basis without providing the ability and agility to control a pandemic if and when it happens. We need coordination, speed, clear decision-making and lines of authority, and surge capacity, not more permanent hospital beds. We have a dysfunctional and expensive ‘sick care’ system that doesn’t deliver health improvement to a large portion of the population. It needs to be reconfigured; we have learned enough from the covid crisis to make it happen.

***

Carol Kellermann was president of the Citizens Budget Commission from 2008 through 2018. Stephen Berger was Chairman of the New York State Commission on Health Care Facilities in the 21st Century.

***

Have an op-ed idea or submission for Gotham Gazette? Email This email address is being protected from spambots. You need JavaScript enabled to view it.

Peaker Plants Harm Communities of Color; It’s Time for New York City to Replace Them

A peaker plant

As the weather warms and we head into the summer, we again expect record-breaking temperatures. Thousands of New Yorkers worry about accessing air conditioning units and surviving a hot summer in cramped apartments, and many will struggle to balance higher electricity bills from air conditioning against costs of health care, food, and rent. But most people don’t worry about the increased electricity demand from widespread air conditioning use during hot days and heat waves.

Most New Yorkers are unlikely to know about the polluting power plants located primarily in communities of color and low-income communities like the South Bronx and Sunset Park that fire up to meet peak electricity demand in New York City when millions of air conditioning units are running.

These half-century-old fossil fuel power plants, known as “peaker plants,” spew high levels of fine particulate matter and nitrogen oxides into the air in communities already burdened with other polluting facilities such as solid waste transfer stations and crowded truck routes. On the hottest days of the year, when air quality is already poor, turning up the air conditioner in Manhattan can mean even more air pollution in environmental justice communities like Sunset Park, Mott Haven, and Hunts Point, where childhood asthma rates are more than double other areas in the Bronx.

New research closely links chronic exposure to higher levels of air pollution such as fine particulate matter and nitrogen oxides to higher mortality rates from COVID-19. Long-term exposure to high levels of air pollution, along with extreme heat, subject already vulnerable communities to greater rates of hospitalization and death from climate events. Health disparities are exceptionally prevalent in neighborhoods like Sunset Park where 22% of the community does not have access to health coverage.

New York City must update the current polluting, inefficient, and inequitable energy system for meeting peak electricity demand in order to reduce pollution and protect health in vulnerable communities, enhance community resiliency, and create green jobs.

New York City’s peaker plants are a prime example of environmental discrimination: the disproportionate burden of pollution and environmental health hazards inflicted on communities of color. Studies have shown that Black and Latino communities across the United States suffer disproportionate levels of air pollution, even as the most privileged are disproportionately responsible for the consumption of goods and services that generate this pollution. Neighborhoods like Hunts Point and Mott Haven in the South Bronx rank highest on the city’s heat vulnerability index, but have one of the lowest shares of air conditioner ownership in the city. These neighborhoods are home to four peaker plant turbines that run among the most frequently of all the city’s 16 peaker plants – often on hot, poor air quality days.

Pollution isn’t the only problem with peaker plants. As revealed in a report released this month by the newly formed PEAK Coalition, peaker plants are a huge expense for electricity customers. Over the past decade, the city’s peaker plants have cost city residents approximately $4.5 billion in electricity bill payments. And this price tag isn’t even for use of the peaker plants – it’s simply the cost of having the peaker plants sit around, available for use in case they’re needed on those peak-demand days. Most of the money has gone to private, out-of-state companies that own the oldest and most polluting plants in the city’s peaker fleet. Spending billions of dollars going forward to prop up the use of antiquated fossil fuel power plants with few to no pollution controls makes no sense.

The solution isn’t for New Yorkers to stop using air conditioning or to feel guilty about it – access to adequate cooling during dangerously high heat days should be a human right, not a privilege. The city must update the current polluting, archaic, and inefficient system for meeting peak electricity demand and replace fossil fuel peaker plants by investing in energy efficiency upgrades, large-scale renewable energy generation and battery storage, and distributed smaller-scale renewable energy generation and storage. Renewable energy and storage will not only reduce air pollution but can also enhance community resiliency in the face of storms or blackouts and create green, local jobs and workforce training opportunities.

Under New York’s groundbreaking climate law passed last year, the Climate Leadership and Community Protection Act, the state must reform this system to achieve a carbon-free electricity generation system by 2040. But there is no need to wait that long – the technology exists to transform the system. We just need a commitment to prioritize the health and resilience of our neighborhoods. Communities like the South Bronx and Sunset Park, among the hardest-hit in the current pandemic, can’t afford to wait another 20 years to reduce air pollution.

***

Rachel Spector is Director of Environmental Justice at New York Lawyers for the Public Interest; Elizabeth Yeampierre is Executive Director at UPROSE; and Dariella Rodriguez is Director of Community Development at The Point CDC. All three are members of the PEAK Coalition. On Twitter @NYLPI & @UPROSE & @THEPOINTCDC.

***

Have an op-ed idea or submission for Gotham Gazette? Email This email address is being protected from spambots. You need JavaScript enabled to view it.