Madrid Demonstrates Successful Civic Engagement. Let’s Pay Attention as We Launch New York City Commission

(photo: @decidemadrid)

Madrid turns its residents’ collective passions and intelligence into tangible improvements to city life. New York should do the same.

New Yorkers had until February 22 to apply to join the Civic Engagement Commission (CEC), a new entity that city voters approved last election to manage civic engagement processes throughout the city. The commission, which will be officially named in April by a variety of elected officials including the Mayor, has a broad mission and three specific mandates: to improve language access at polling places, expand participatory budgeting citywide, and help nonprofits with civic engagement efforts.

Even though these three mandates might seem disjointed, the commission could still be a success. But what does successful civic engagement look like? It looks like Madrid.

History won’t explain why Madrid is so good at civic engagement, but Decide Madrid (decide.madrid.es), the city’s official participatory decision-making website, will. Decide is a custom-built, open-source website developed by Madrid’s city council to provide a single online location for the city’s public decision-making processes: participatory budgeting, resident petitions, legislation feedback, and more.

By placing all these civic processes into one software platform, Madrid reduces the costs of organizing for government, and streamlines participation for users. Over 400,000 of Madrid’s 3 million residents have accounts, making it the largest system of its kind in the world - and the most impactful.

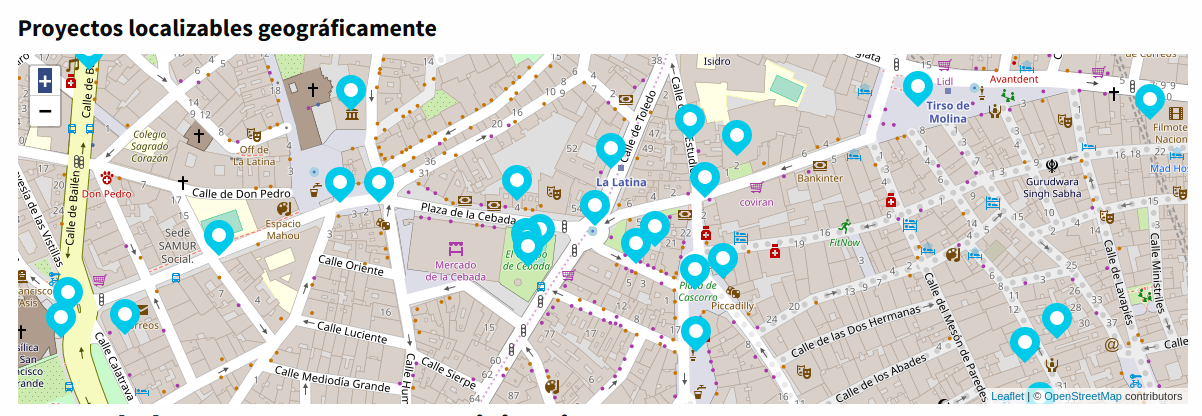

Decisions made on Decide are genuinely important. If a resident’s petition reaches a certain threshold, then the city government is required by law to come up with an implementation plan that will then go up for a city-wide referendum vote. The participatory budgeting projects are funded to the tune of $100 million a year, making it one of the world’s largest participatory budgeting processes. Every comment made on legislation posted to the platform gets a response from a city staffer. And Madrid is beginning to leverage the system for more complex tasks like decisions related to land-use and public-space renovations.

Decisions made on Decide are genuinely important. If a resident’s petition reaches a certain threshold, then the city government is required by law to come up with an implementation plan that will then go up for a city-wide referendum vote. The participatory budgeting projects are funded to the tune of $100 million a year, making it one of the world’s largest participatory budgeting processes. Every comment made on legislation posted to the platform gets a response from a city staffer. And Madrid is beginning to leverage the system for more complex tasks like decisions related to land-use and public-space renovations.

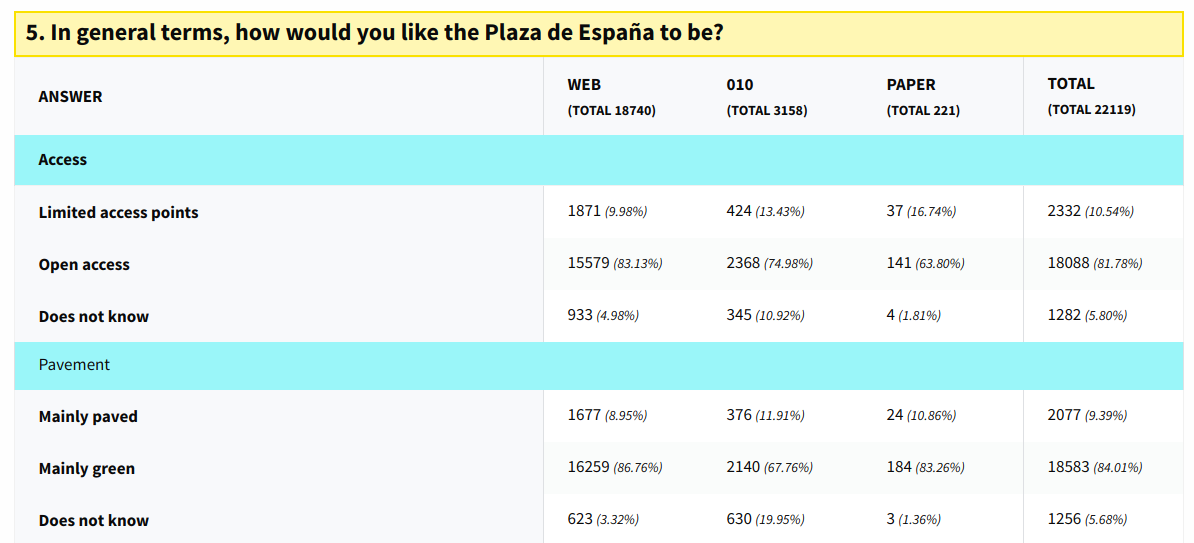

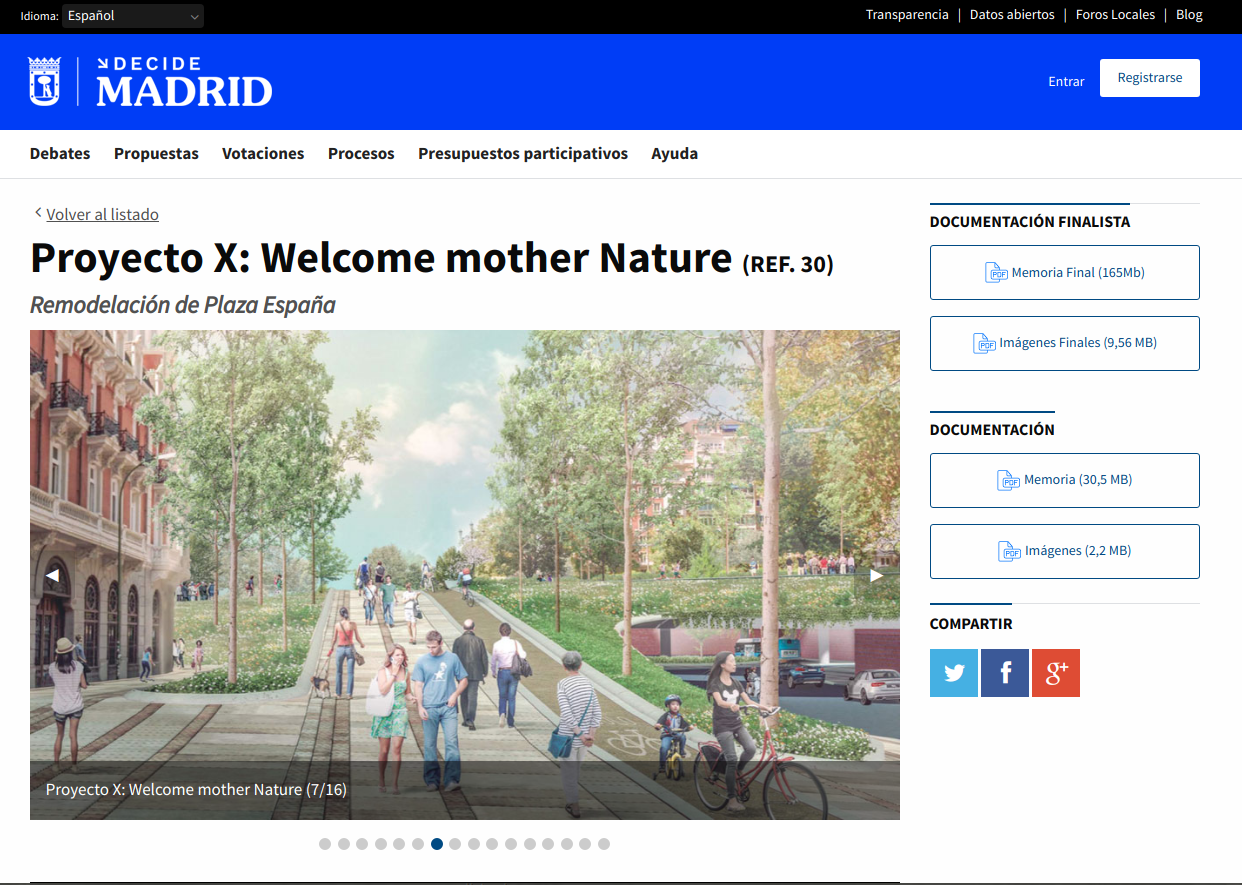

The recent multi-phase process for redevelopment of Plaza Espana, one of the city’s most important public spaces, was a major milestone. The process began with an 18 question survey filled out by over 20,000 people. The results were made public and then used to inform resident proposals, which anyone could post to the website. The public then gave feedback on each proposal via comments, and indicated opinions by clicking a thumbs-up or thumbs-down icon. The most popular projects advanced to the next round where they were evaluated by a jury of experts who worked with the finalists to merge the most popular features into two final proposals, which went up for public referendum where residents picked the winning design.

Whether you're looking at big processes like the Plaza Espana redevelopment, or the thousands of resident-generated participatory budgeting project proposals posted to the site for the 2018 funding cycle, one thing is abundantly clear: Madrid has found a way to turn its residents’ passions and intelligence into tangible improvements for the city. And the public loves it.

Polls for the upcoming mayoral election show Mayor Manuela Carmena, who made the development and use of Decide a central piece of her first campaign and mayoral administration, is ahead by a wide margin and has never been more popular. The conservatives, who ruled Madrid from 1991 to 2015, are in disarray and the traditional socialist party, which ran against her in the last election, has offered her leadership in their party. She has refused.

This leads to an obvious question: is the key to improving the quality of life in a city giving residents the power to make more direct decisions about their government’s actions? Fortunately, Madrid wants us all find out.

The software powering Madrid’s Decide website was built by Madrid’s Office of Civic Participation. It turned the code into an open source project called Consul that anyone can download for their own use. And that’s exactly what has happened: over a dozen cities in Spain and nearly 100 governments around the world, including large cities like Buenos Aires and Quito, are using Consul for participatory processes. Software developers in these cities are also contributing code back to the project, enabling Madrid to benefit from the global public’s collective intelligence.

And we in New York City can too - but only if we commit to using best practices and open source tools from around the world to do so. Madrid shows us how. We should leverage their success and follow in their footsteps. The soon-to-be-named Civic Engagement Commission that was popularly approved by voters last year is a perfect opportunity.

***

Devin Balkind is the president of Sahana Software Foundation, founder of Sarapis.org, and a former candidate for New York City Public Advocate. He speaks regularly at conferences around the world about using technology to overcome environmental and political crisis. On Twitter @DevinBalkind.

***

Have an op-ed idea or submission for Gotham Gazette? Email This email address is being protected from spambots. You need JavaScript enabled to view it.

Rep. Nydia Velázquez: My Campaign Finance Pledge

Rep. Nydia Velázquez (photo: William Alatriste/NY City Council)

When I first ran for Congress, I faced what observers said were impossible odds. No Puerto Rican woman had ever served in Congress, the incumbent was sitting on a $2 million war chest, and I was taking on a powerful party machine determined to stop me. Yet, I won.

What guided me in that first race, and every election since, has been my neighbors’ voices, which I have continued to rely on—from town halls to street corners to knocking on doors. My opponent back then spent close to $6 million in today’s dollars, much of it coming from big corporate backers, but it couldn’t outweigh the importance of person-to-person conversations with real voters in our community.

Like anyone running for office, I’ve had to raise money over the years, but I’ve always prioritized community organizing and constituent contact over fundraising. While it has long been apparent that our campaign finance system is far from ideal, its problems have grown exponentially worse since Citizens United. That ruling set the stage for an unprecedented influx of corporate money in our political system. It also helped undermine our national political culture. The sheer volume of money aimed at influencing electoral outcomes has bred a degree of distrust among voters more severe than I can ever recall since entering public life.

This growing cynicism is bad for our city and our nation. Over the long term, I worry that corrosion of voters’ trust in government threatens our democracy’s health, weakens our civic institutions, and makes policy-making worse.

For these reasons, I have made the decision starting this year to stop taking corporate PAC money. What was true before, will be transparent forevermore: the decisions I make and the work I do is on behalf of New York’s working families; not those with a corporate ledger.

It is my belief that we are in a unique moment in our political history, making this decision the appropriate step for my campaign, right now. I am proud to join the many Democrats elected in 2018 who have already taken this pledge. Over half (36 of 62) of the Democrats newly elected to Congress last year have committed to do this, but only seven returning incumbents have joined them so far. That needs to change—and as a longtime progressive leader in Congress, I hope others will join this call.

In my fights for progressive values here in New York, I have been blessed to build community support for allies who have taken similar steps. In 2013, again facing a predatory party boss, we elected a slate of reformers to the City Council who stood against big-moneyed special interests. In 2018, we took on corporate-backed Democrats who sided with Republicans and real estate interests to elect a crop of reformers to the New York State Senate.

Throughout my time in public office, I have always taken on entrenched interests, whether it is party bosses trying to impose a chokehold on local politics or big companies seeking to undermine environmental and consumer safeguards or profit off the sick and the vulnerable. My commitment to those core values has not and never will waver. But, it is my hope that no longer accepting corporate PAC money will send a powerful message to my constituents and my Congressional colleagues that the time for additional change has come.

Make no mistake: curing what plagues our political system will require more than elected officials foregoing corporate PAC money. That’s just one piece in a complicated puzzle. For instance, I will also push for the passage of a statewide public campaign finance system in New York that bans corporate money and emphasizes small-dollar, individual contributions.

Another problem: since Citizens United, so-called Super PACs injected more than $1 billion into federal elections in 2016 alone, without meaningful transparency. Fixing that problem will almost certainly require legislation. Likewise, we need to be working at both the state and federal levels to reduce voting obstacles. Faith in government didn’t erode overnight and won’t be immediately fixed either. Nonetheless, greater transparency in campaign finance and boosting voter participation can help. Those goals will require more work, but they are certainly worth pursuing.

For now, turning away corporate PAC dollars is the right decision for me, my campaign, my community and, most of all my constituents. Ultimately, we are elected to lead and, as more members of Congress follow suit, this can be a modest, but meaningful step toward restoring trust in public service.

***

Rep. Nydia Velázquez represents parts of Brooklyn, Manhattan, and Queens in Congress. On Twitter @ReElectNydia.

***

Have an op-ed idea or submission for Gotham Gazette? Email This email address is being protected from spambots. You need JavaScript enabled to view it.

Are the Votes There to Pass Congestion Pricing Through the State Legislature?

(photo: governor's office)

It’s decision time for the New York State Legislature on the State budget, due March 31, and it’s still not clear congestion pricing has the votes to pass. I’ve been an advocate for congestion pricing since Mayor Bloomberg first proposed it in 2007 and I know that this is the year to get it done.

The two houses of the State Legislature each pass a “one-house” budget resolution in early March to outline their budget priorities: this year the State Assembly one-house budget articulates that the Assembly majority supports a new long-term source of revenue for the MTA but does not specifically endorse congestion pricing. The State Senate one-house budget contains an articulated statement of support for congestion pricing. But no bill for congestion pricing has actually yet passed either house as the budget deadline approaches.

I was fortunate to serve in the Democratic majority my entire 32 years in the State Assembly, from 1985 through 2016; a legislator in the minority party frequently has little chance of getting many of their bills to pass. There are 150 members of the State Assembly and the Democratic majority frequently exceeded 100 in my years there; it is 107 right now.

The rule of thumb for putting a potentially controversial but important bill to a floor vote for passage in the Assembly has been that it needed 76 guaranteed Democratic votes, just over half the chamber, and today that means 76 out of the 107 Democrats, without relying on any Republican support. Usually this wasn’t a serious problem, in fact many bills are noncontroversial or routine and frequently pass with large numbers of Republicans voting for them too. A bill without that kind of support going to the floor has been quite rare.

Substantial opposition to congestion pricing has been the reason the proposal was never brought to a vote in the Assembly when Michael Bloomberg was Mayor in 2007 and 2008, or when Governor Cuomo announced he was backing it last year. It is why the governor, the Assembly, and the Senate have yet to announce a deal on this concept with less than 10 days before the budget deadline. If Speaker Heastie determines a congestion pricing bill might have 32 Democratic votes against, and therefore at most 75 Democratic votes, he probably wouldn’t put it on the floor for a vote, especially if there was a risk that all 43 Republicans would vote against it.

Are 32 Democratic Assembly votes against congestion pricing a real possibility? The answer is yes - a real possibility - or it could be extremely close to 32, with a number of members on the fence or not wanting to be forced to take a vote on the issue. There is substantial opposition in Queens, where there are 17 Democratic members, and, to a lesser extent, Brooklyn, which has 20 Democratic members, where opposition in the southern and furthest east sections of the borough was substantial at the time I was serving just a few years ago.

There are ten Democratic members from Long Island, including several just recently elected who might be concerned about taking a risky vote, two Democratic members from Staten Island, and four Democratic members from Rockland, Orange, and Sullivan counties where many people who work in the city drive in and where mass transit options north and west of the Hudson River to New York City are not good. There are seven Democratic members from Westchester and there is no guarantee all of them will vote for congestion pricing, nor is there a guarantee that all 22 members from Manhattan and the Bronx will vote yes.

One possibility is that the language authorizing congestion pricing will simply be put into a bigger budget bill, such as the main bill authorizing the transportation and economic development budget as a whole. Since there would be tens of billions of dollars of general road, bridge, and mass transit financing in such a bill, a member would have to vote against the whole package, including things he or she might want, just to vote no on congestion pricing. This is always the dilemma of large authorizations for funding packages, but effective for accomplishing a result despite opposition inside the majority party.

Should congestion pricing fail, there are plenty of alternatives but they might face other political problems. Revenue from state taxes is $80 billion a year, three-quarters of which comes from the metropolitan area, and New York City tax revenue is $60 billion a year. Governor Cuomo was seeking about $1 billion a year from congestion pricing - just a fraction of the revenue base of the metropolitan area. However, without congestion pricing, some fraction of a broader-based tax would likely have to be enacted. The new Senate Democratic majority, however, is aware Republicans are gunning for them in the next election, and might be reluctant to consider any tax increase that is broad-based.

If congestion pricing passes, it will be a major victory for mass transit, and I remain hopeful. The list of other severe challenges for the MTA is large and will hardly go away, but that can be the subject of another discussion.

***

Jim Brennan was a member of the New York State Assembly for 32 years, where he chaired four committees. On Twitter @JimBrennanNY.

***

Have an op-ed idea or submission for Gotham Gazette? Email This email address is being protected from spambots. You need JavaScript enabled to view it.