Providing Stronger Support for Breastfeeding Mothers in New York City

Council Member Laurie Cumbo, the author (right), with her son, Prince (photo:@cmlauriecumbo)

If we are truly committed to the health, well-being, and economic advancement of mothers and babies, we must examine our public spaces, work places, and cultural biases when it comes to supporting and accommodating a mother’s choice to breastfeed. As of only a few weeks ago, mothers can now breastfeed legally in all 50 states without fear of violating laws pertaining to indecent exposure or public obscenity. This is a low bar for celebration, and cause for a critical examination of our own local laws and societal norms.

The benefits of breastfeeding are long-known and widely accepted in the medical community – the World Health Organization recommends that babies are breastfed for at least the first six months of their lives. The health benefits for babies include lower rates of obesity, SIDS, asthma, and other conditions, and can even be traced to higher IQs. For mothers, breastfeeding lowers the risk of type 2 diabetes, and certain types of ovarian and breast cancers. It is for these reasons, and for the purpose of defending a mother’s right to choose what they do with their bodies and how they take care of their children, that we must remain diligent in our efforts to identify and break down any barriers for mothers who choose to breastfeed.

Those of us holding elected office must all leverage our positions and platforms to advance breastfeeding rights and awareness. We must make sure that mothers know all the facts about breastfeeding, what they are entitled to and what resources are available to them, should they choose to breastfeed.

Here, in New York, we have strong laws and we are increasing our investment at the state and local level in support of breastfeeding mothers. I am proud to have made breastfeeding rights a focal point of my time in office, with legislation advancing greater education and access for those who need to breastfeed or express milk in public or in the workplace. Right now, the Mother’s Day Legislative Package, which I was proud to spearhead on my very own first Mother’s Day, has pending legislation that will expand accommodations for breastfeeding mothers in certain city spaces and in workplaces, as well as establish a standard lactation accommodation policy. I thank my colleagues, Council Members Robert Cornegy and Carlina Rivera, for their leadership and partnership on these breastfeeding bills. I am committed to seeing through these efforts and ensuring that our physical structures reflect our values of equity and inclusion.

As a mother of a now one-year-old myself, I have a new appreciation for and understanding of the literal and figurative structures that play a role in the lives of New York mothers. From pre-natal care to childbirth and child rearing, there is a culture of expectation that women are just supposed to know how to take care of themselves and their children based on instinct alone. Far too many women are not getting the resources they need. Further, as recent research has shown, health concerns expressed during childbirth are often not taken seriously, resulting in a much higher mortality rates for black and Latina women. The truth is, we all need guidance and support throughout the pregnancy, birthing and nurturing process, which is why we must continue to expand and center the needs of mothers in public and working spaces. Every mother is different, as is every child, and our ultimate goal should be to support and uplift all mothers, regardless of whether they choose to breastfeed.

One personal breastfeeding experience of note was when I was able to use one of the Department of Health’s “lactation pods” at Brooklyn Children’s Museum. What struck me about my experience was how welcoming the environment was. Breastfeeding is often framed as an inconvenience, but in this instance, I felt proud and encouraged. The unfortunate reality is that this is an uncommon experience for breastfeeding mothers. More often than not, new mothers in the workplace have to seek out any space they can find — some report even having to pump in a closet. This is inexcusable and detrimental to the dignity and well-being of working mothers everywhere.

It is going to take a dedicated, comprehensive approach and a fundamental reimagining of working motherhood, but I know that we can achieve it. Moms continue to show up for each other, time and time again, but it is time we show up for them. We must stand with them and do everything in our power as individuals and as a collective society to better support their needs. Breastfeeding takes a village. It is a mental, physical, emotional, and logistical act. August is National Breastfeeding Awareness month, and so there is no better time than now to commit to a better tomorrow for mothers and children in New York City.

***

Laurie Cumbo is the majority leader of the New York City Council. She represents Brooklyn communities of Fort Greene, Clinton Hill, Prospect Heights and parts of Crown Heights and Bedford-Stuyvesant. On Twitter @cmlauriecumbo.

***

Have an op-ed idea or submission for Gotham Gazette? Email This email address is being protected from spambots. You need JavaScript enabled to view it.

New Research Shows SHSAT Less Valuable Predictor Than Middle School Grades

Mayor de Blasio's announcement on specialized high schools (photo: Benjamin Kanter/Mayor's Office)

The recently-released Metis validation study of the Specialized High School Admissions Test has portrayed the SHSAT in a more favorable light than the facts warrant.

Although Metis found that SHSAT scores were correlated with high school grades, it did not investigate whether other factors might be stronger predictors. In my validation study, the most important finding was that seventh grade GPA predicts more than twice as much of the variance in high school grades (44%) when compared to the SHSAT, which predicted 20% in my study and 21% in the Metis study. This finding is critical to the current debate over the admission system at New York City’s Specialized High Schools.

Mayor Bill de Blasio, along with many advocates and civil rights groups, have proposed doing away with the test, with a three-year phase-out period where the test is used along with grades for admissions purposes. Their opponents have argued that allowing grades as a factor would dilute the quality of the students admitted and thus the quality of these schools, an argument that is rebutted by my analysis.

This study uses data supplied by the New York City Department of Education, including the 27,818 SHSAT scores from 2013, and grades for New York City public school students in that cohort.

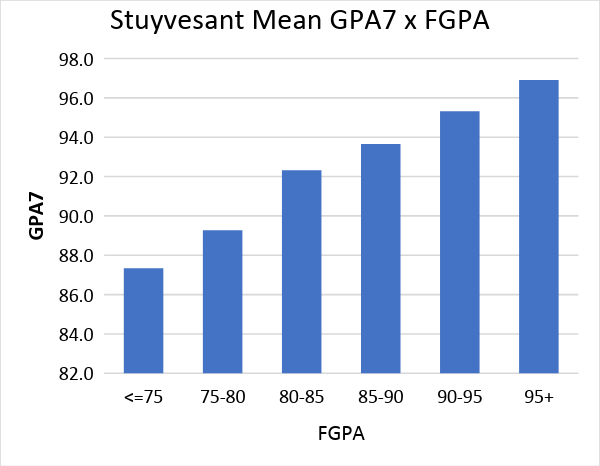

The chart below compares mean SHSAT scores for students at Stuyvesant High School with their Freshman Grade Point average (FGPA) in different FGPA categories. Students with FGPAs below 75 actually had higher SHSAT scores than students with FGPAs from 75 to 85, while students with FGPAs of 85 to 90 had barely higher scores. Only the students with grades above 95 had much higher scores. This suggests that the exam does not predict very well for students with scores below the very top.

The next chart, which compares the same categories of FGPA by seventh grade GPA (GPA7) of Stuyvesant students, instead of their SHSAT scores, shows a much more linear relationship. Higher FGPAs were associated with higher GPA7 in a regular progression.

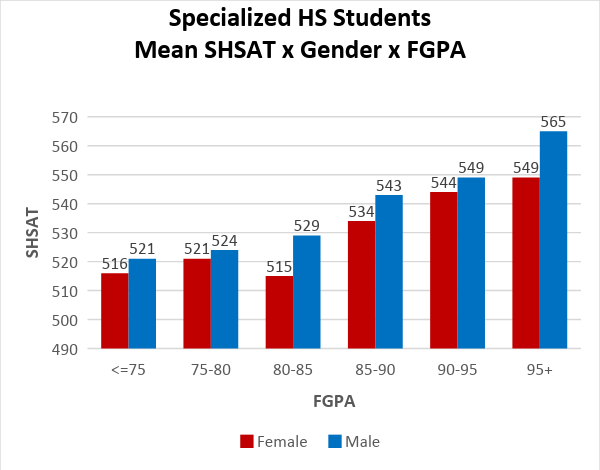

As is well known, girls are admitted to the specialized high schools at much lower rates than boys. Below is the chart with the rates by gender for those students who took the test last year, when girls represented 51% of applicants and only 44% of those admitted.

A good study of predictive validity should address the gender bias of the exam. According to American Educational Research Association standards, the test user is “responsible for evaluating the possibility of differential prediction for relevant subgroups for which there is prior evidence or theory suggesting differential prediction.” Prior evidence with respect to the validity of the SAT suggests that possibility. Yet, the Metis study failed to do this, despite the fact that girls are under-represented in the Specialized High Schools.

In my study, girls had lower SHSAT scores than boys with the same GPA. For example, at Stuyvesant High School, girls had GPAs equal to GPAs of boys whose SHSAT scores were 6 to 7 points higher. The following chart shows that girls (red bars) achieved each FGPA level with lower SHSAT scores than boys (blue bars). Among students in 95+ FGPA group, girls (549) had mean SHSAT scores 16 points lower than boys (565). This chart helps explain why fewer girls are admitted to the Specialized High Schools than boys.

The gender bias of the SHSAT parallels findings with respect to the predictive validity of the SAT. However, there is a crucial difference in how the scores are used. The SAT is only one of multiple criteria considered in college admissions, including high school grades, which enables admissions officers to take that statistical bias into account. In New York City, where the SHSAT is the sole admissions criterion for eight schools, girls with lower SHSAT scores than boys are denied admission despite the fact that they are expected to do as well as boys admitted with higher scores. It is clear that as the sole admissions criterion to the Specialized High Schools, the SHSAT is unfair to girls.

A variety of analyses were done to rule out the possibility that the under-prediction in girls’ grades resulted from differences in course selection. Because the under-representation of females in STEM majors and occupations has been a source of societal concern, it was of special importance to examine the relationship between SHSAT scores and girls’ grades in STEM areas, and to ascertain whether girls in New York City’s Specialized High Schools enroll as frequently and do as well as boys in challenging STEM courses.

Gender comparisons were done across different academic domains for all students who took the SHSAT in 2013 and subsequently attended New York City high schools. Similar comparisons were done for those who actually attended Specialized High Schools. Finally, analyses were done at Stuyvesant High School, which, because it is the most selective of the schools, might possibly have the most difficult courses. Overall, girls earned significantly higher grades than boys in each of these categories. At the Specialized High Schools, girls had higher mean STEM grades (89.6) than boys (86.7) and enrolled in STEM courses in proportion to their overall numbers in these elite schools.

Grades in specific courses offer the best test of the hypothesis that girls are less capable of succeeding in STEM subjects, and that the under-prediction of their grades by standardized tests such as the SHSAT is due to enrollment in easier courses. At Stuyvesant High School, girls, on average, earned better grades than boys in each of the ten specific STEM courses analyzed, including Geometry, Integrated Algebra, Biology, and Physics. In four of the ten courses, girls were represented in greater numbers than in the overall Stuyvesant ninth grade cohort. Furthermore, their grades were significantly under-predicted by the SHSAT.

In 2005, Lawrence Summers, then president of Harvard, suggested that the reason there were fewer women in STEM fields was their under-representation at the highest level of the distribution of ability in STEM subjects. Because one of the goals of the Specialized High School admissions process is to identify truly exceptional students, it is important to determine if the higher mean grades earned by girls in STEM classes were achieved without those extreme high-achievers. It would be possible for girls to have higher mean grades, but fewer exceptional grades. However, this is not the case. Girls represented only 42% of the cohort and only 41% of the top 3% of SHSAT scores, but in STEM courses they earned 50% of the grades of 95 or better, and only 30% of grades 80 or lower.

Why should females earn better grades than predicted by their performance on the SHSAT and SAT? Research has repeatedly shown that women do poorly relative to men on multiple choice questions. In addition to the SAT, this phenomenon has been found on a wide range of exams, including AP exams, placement exams, and the California State Bar Exam. One researcher attributed this to women on average being more risk-averse, and therefore not guessing as often as males, although guessing on multiple choice tests is often a useful strategy.

Because women often outperform men on constructed answer questions, it seems possible that multiple choice and constructed answer questions tap different competencies on which there are real gender differences. Constructed answer questions, particularly essays, may require multiple abilities, and may reflect a more complex understanding of material than do questions that require only the selection of a correct choice. If multiple choice and open constructed answer questions measure important, but different abilities, in the interest of fairness, exams should include both types of questions. Given that the purpose of the SHSAT is to admit a class with the greatest chance of success at school, it is apparent that the same metric cannot be used for boys and girls, and that the exam should be reformulated to include questions in different formats.

Our analysis also found that New York state exams were somewhat less gender-biased than the SHSAT, and somewhat more predictive of success in high school, perhaps because they contain more open-constructed answer questions, though again, 7th grade GPA is the most valid predictive factor for success at New York City high schools in general, including the Specialized High Schools.

A hypothetical admissions index was constructed weighting SHSAT and GPA7 by coefficients from the regression of FGPA. The index was then used to simulate admissions to the Specialized High Schools, resulting in the proportion of girls “admitted” rising from 45% to 62%, a difference of 716 girls. At Stuyvesant, using the index, the representation of girls increased from 44% to 65%, a difference of 177 girls. If GPA7 were the sole admissions criterion, the proportion of girls would have been 68%, a difference of 202 girls.

Use of this index would also have resulted in substantially different racial/ethnic proportions. At Stuyvesant, for example, an additional 10 African-American and 25 Hispanic students would have been admitted. Asian students, though reduced in numbers from 78% would still comprise 66% of those admitted. Similar shifts would occur in the entire cohort of students admitted to Specialized High Schools, with increases of 40 African-American, 209 Hispanic, and 205 white students. With 49% of the hypothetically admitted class, Asian students would still constitute the largest segment and would be admitted in numbers far exceeding their proportion of applicants (32%).

Because the hypothetical criterion predicts far more variance in FGPA than the actual criterion, with a smaller standard error of estimate, its use should not dilute the quality of the entering class. In fact, it might even result in a stronger cohort, while simultaneously increasing diversity and gender equity.

With changes to the SHSAT and consideration of additional criteria, it may be possible to select a group of students who will be more representative of the community the school system serves, and the pool of students who apply, without sacrificing the excellence for which New York City’s Specialized High Schools are so justifiably famous.

***

Jonathan Taylor, Ph.D. is an educational research analyst.

***

Have an op-ed idea or submission for Gotham Gazette? Email This email address is being protected from spambots. You need JavaScript enabled to view it.

Keep Tips and Save Jobs in Communities of Color

(Photo: Lou Stejskal/Flickr)

As New York City businesses and their employees continue to adapt to shifting consumer habits, online competition, and increasing costs of doing business, New York State is dangerously close to further damaging the chances of business and employee success by eliminating the tipped wage credit.

This tip credit allows restaurant owners to pay tipped workers $8.65 per hour so long as tips ensure that the employee is earning at least the minimum wage at the end of the day.

The city’s family-owned restaurants and cafes aren’t shortchanging their employees to make a quick buck – they’re trying to make ends meet and take care of their servers at the same time. Surveys show that, on average, tipped workers end up earning as much as $25 an hour, with tips.

In this city, it’s notoriously difficult for locally owned and operated restaurants to survive.

As one restaurant owner from Harlem told me, “My customers expect me to compete with the best food and the best service as the best restaurants in town, but they want Harlem prices. It’s very hard and eliminating the tip credit will push me over the edge.” This is the sentiment throughout the city’s less affluent areas and outer-boroughs, where restaurant owners of color have been fighting to keep the tipped wage credit in place.

We celebrate birthdays, anniversaries, and graduations at family-owned neighborhood restaurants; they’re essential to the economic and cultural vitality of communities of color in every borough. They employ locals, from a handful to a few dozen each, and sometimes those employees have been with them for decades. These jobs are important to these workers and their families, and when tips are included, they are paid well over the minimum wage.

Most restaurant owners care deeply about their servers and want to pay them as best they can while still staying in business. If New York State eliminates the tip credit, labor costs will soar, jumping approximately 50 percent overnight. That massive increase will force tough choices, starting with cutting employees and reducing hours. But fewer employees means slower service, and no restaurant can survive a reputation for poor service. It’s a downward spiral that will close many restaurants permanently, and communities of color can least afford it.

We support good-faith, smart solutions to increase wages sustainably and fairly and promote small businesses throughout the city. That’s why we need to preserve the credit for tipped workers. These workers don’t want to lose their tips and can’t afford a pay cut. And they certainly don’t want to lose their jobs. This is a critical issue for communities of color, and our state leaders must get right – or risk causing more harm than they intend.

***

Jessica Walker is President of the Manhattan Chamber of Commerce. On Twitter @jessinharlem & @ManhattanCofC.

***

Have an op-ed idea or submission for Gotham Gazette? Email This email address is being protected from spambots. You need JavaScript enabled to view it.