How Bill de Blasio Can Redeem His Education Record

Mayor de Blasio at a town hall (photo: Benjamin Kanter/Mayor's Office)

Bill de Blasio was re-elected as mayor and will remain in control of our public schools for four more years, unless the Legislature amends mayoral control or allows it to expire in 2019. It was recently announced that Carmen Fariña, de Blasio’s hand-picked schools chancellor, will be leaving and a “national search” has begun to find her replacement. We urge the mayor to involve the public in the selection process, as he promised during his first campaign but failed to follow through on when selecting Fariña.

Instead, he apparently plans a “quiet internal decision.” Yet by opening up the process, he would have the benefit of a wider choice of candidates, and by involving parents, he would be better able to ensure that the next chancellor is more responsive to their concerns.

One of us is a long-time parent advocate and the other is the former president of the Community Education Council in District 2 in Manhattan – although what we say here only represents our own personal views. We are also members of NYC Kids PAC, which released a mayoral report card this fall, in which we gave de Blasio and his chancellor low grades in many education areas, surprising city residents who do not have children in the public schools. The reasons are myriad.

The mayor continues to underfund our schools, and most schools still receive only 87% of the amount promised when the Fair Student Funding formula was devised ten years ago, despite increased costs and repeated city surpluses. This underfunding has contributed to larger classes and inadequate services at many schools. Meanwhile, the number of top-level administrators has nearly doubled, with 70% more spent on central staff bureaucracy than during the last year of the Bloomberg administration, and with 34% more spent on central staff expenses.

The mayor renounced his earlier campaign promise to parents to lower class size, and the chancellor repeatedly stated in public meetings that she has been more concerned that classes can be too small -- despite the fact that New York City students continue to suffer from the largest classes in the state. The number of students in grades one to three in classes of 30 or more has increased by nearly 3,800 percent since 2007 and more than 290,000 students -- nearly one-third of the total -- are crammed into classes this large. The city’s refusal to act to lower class size prompted a legal complaint against the DOE, filed with the State Education Department this summer.

Meanwhile, more than half a million students are currently attending overcrowded schools.

With the student population growing in many parts of the city, the school capital plan will create only about half the seats required to alleviate overcrowding, according to the DOE’s own estimates. And while Mayor de Blasio has delivered on his promise to expand pre-kindergarten, the administration has pushed the program into many schools where it worsened overcrowding and contributed to larger class sizes. As more than 73 professors of education and psychology pointed out in a letter to the Chancellor Fariña, many of the benefits of expanded pre-K will likely be undermined because of the administration’s refusal to address the need to lower class size in other grades.

Forty million dollars per year has been spent on consultants and bureaucrats to oversee the struggling schools in the Renewal program, many with records marked by scandal or found to be incompetent in previous positions. Though the DOE made special promises to the state to reduce class size in these schools, nearly three-quarters continue to have maximum class sizes of 30 or more; and in nearly half, average class sizes have not decreased by even one student. It is no surprise that by most accounts, improvements in these schools have not been impressive, with one-third facing or having already experienced merger or closure.

Too often the chancellor has left administrators in positions where they have abused their authority. It took nearly a year of intense student protests before Rosemarie Jahoda, the acting principal at Townsend Harris High School, was removed, even after nearly every local Queens elected official asked for her dismissal. Chancellor Fariña was also deaf to the entreaties of parents at Central Park East 1 for over a year. They pointed out how their principal was violating the progressive and collaborative traditions of the school. In other instances, the chancellor left corrupt principals in place when they engaged in rampant fraud, including Kathleen Elvin, who remained the principal at John Dewey High School for nearly two years, despite numerous news reports exposing her schemes to inflate the school’s graduation rate.

While running for office, Mayor de Blasio promised to lessen high stakes testing and make school admissions based on more holistic factors. Yet in 28 out of 32 districts, admissions to gifted programs are still based solely on a single high-stakes exam. The same is true for admissions to the eight specialized high schools, even in the five schools where this is under the mayor’s sole control; and too many other middle and high schools continue to use test scores as central factors in their screening process.

Though de Blasio also promised to “develop a non-punitive process” to allow parents to opt their children out of standardized testing, the chancellor has failed to respect the resolution passed by the City Council which calls upon the DOE to include information about this in its Parent's Bill of Rights.

For many of us, the realization that New York City is one of the most segregated public school systems in the nation was appalling, and yet Chancellor Fariña suggested that this problem could be addressed by encouraging wealthy students to become pen pals with poor students in other public schools. After much public pressure, the mayor and the chancellor finally released a diversity plan last spring, yet an analysis by the Center for New York City Affairs found that its goals were so weak they could be met if current demographic trends continue -- without any actions taken.

The Panel for Educational Policy, made up of a supermajority of mayoral appointees, is still largely a rubber stamp when it comes to approving excessive contracts and damaging co-locations and school closings. The recommendations of parents and teachers on School Leadership Teams are usually ignored, as is the input of parent-led Community Education Councils.

The DOE also suffers from a lack of transparency, and is the least responsive of city agencies when it comes to fulfilling Freedom of Information requests -- taking an average of 103 days to respond. The chancellor insisted on closing meetings of School Leadership Teams, even when a decision by the State Supreme Court concluded that these meetings must be open to the public. She only conceded when the Appellate Court ordered her to reverse course in a unanimous decision.

When he took office, Mayor de Blasio promised to listen to parents and community members rather than treat the Department of Education as his personal fiefdom. Chancellor Fariña announced she would take a new direction based on a “Framework of Great Schools,” involving collaboration and trust among parents, teachers, and administrators. Yet too often that sense of trust has been broken, and the mayor and chancellor have exhibited a regrettable lack of regard for parent views.

We urge the mayor to involve the public in the vetting process for a new chancellor, as he had previously said should be the case. He should announce how individuals can apply for the position, and allow parents and other citizens to ask questions of leading candidates and provide feedback on their responses. In this way, he might be able to redeem his record and raise the chances that our next chancellor will partner with parents and community members to focus on the critical problems that are crying out to be addressed in our schools.

***

Leonie Haimson is the Executive Director of Class Size Matters and Shino Tanikawa is the President of NYC Kids PAC.

***

Have an op-ed idea or submission for Gotham Gazette? Email This email address is being protected from spambots. You need JavaScript enabled to view it.

Contrary to Cuomo Claim, Upstate Economy Faltered This Century, Not Last

Gov. Cuomo upstate (photo: The Governor's Office)

Governor Cuomo described the Upstate New York economy as suffering from a “bad 50 years “ as he tried to explain why it was hard to stimulate rapid growth in the region’s economy, which has grown far more slowly than the rest of the state and nation (see my prior column: Upstate New York is Home to Heavy Voter Turnout, Major State Investment, and Minimal Job Growth).

Cuomo also said that his administration had changed the trajectory upward. Residents of the state should be concerned about how successful these efforts are: Upstate York has more than a third of the state’s residents and is nearly 50 percent of the vote in gubernatorial elections; the state has enacted intensive programming to uplift that region’s economy, and the state must make major decisions about the allocations of its resources and assets every year and set policy directions.

When I wrote the earlier column, I assumed the governor’s description of Upstate’s economic decline was generally true. But in the course of verifying the accuracy of the 50-year decline claim in order to elaborate on the issue, I learned that it was not true.

The Upstate New York economy only slowed to a crawl in the years after 2000, largely due to the two recessions that occurred between 2000 and 2010. This major slowdown did, of course, occur before Andrew Cuomo became governor in January 2011. But a detailed look at the history of the state’s economy and employment growth shows that Upstate New York’s employment growth actually outpaced the rest of the state in the 1980s, and continued a moderate climb forward in the 1990s, although both regions grew more slowly than the rest of the nation. Employment grew 20% in each of the two decades across the United States.

New York State Labor Department figures show Upstate employment growing at 17% in the ‘80s, versus 12% Downstate (1). Downstate consists of New York City, Nassau, Suffolk, Westchester, Rockland, and Orange counties (2). Upstate is the remainder of the state.

|

NYS EMPLOYMENT GROWTH, 1980-90, NY AND REGIONS (000) |

||||

|

1980 |

1990 |

Growth % |

||

|

NYS |

7113 |

8098 |

13.8% |

|

|

Downstate |

4645 |

5206 |

12.1% |

|

|

Upstate |

2468 |

2892 |

17.2% |

|

Governor Cuomo seemingly was expressing a public perception that manufacturing job loss broke the back of the Upstate economy decades ago. Manufacturing job loss has in fact been relentless, in Upstate New York and Downstate New York, and the nation as a whole. In 1979 the United States reached its peak manufacturing employment with 19.5 million jobs. New York’s manufacturing employment history since then, divided between the regions:

|

NYS MANUFACTURING EMPLOYMENT, 1979-90(1),1990-2010(1) (there are two figures for 1990, see footnote (1) below) |

|||||

|

1979 |

1990 |

1990 |

2000 |

2010 |

|

|

Upstate(000) |

707 |

574 |

513 |

421 |

276 |

|

Downstate(000) |

787 |

557 |

468 |

328 |

181 |

In 1979-80, manufacturing jobs were 29% of Upstate New York employment, and 17% Downstate. Manufacturing job losses were seriously affecting employment in New York, but in the 50-year lookback to the late ‘60s and ‘70s, it was New York City’s economy that was in freefall in the early ‘70s. New York City lost 600,000 jobs, including 300,000 manufacturing jobs, from 1969 to 1976 (according to the Federal Reserve Board of New York, quarterly review, summer 1977). But the city economy recovered in 1977 and beyond.

Two recessions, in 1980 and ‘81-’82, hit the steel and auto industries in Western New York hard. The huge Bethlehem Steel plant in Erie County closed in 1982. Erie and Niagara Counties lost 41,000 manufacturing jobs from 1979-85. IBM and Kodak began their manufacturing job declines in the mid-to-late ‘80s and continued through the ‘90s. Despite these cutbacks, the Upstate economy as a whole still continued to expand once the recessions were over and grew by more than 400,000 jobs in the ‘80s.

In the 1990s, both regions saw their employment grow at a pace of about 5% for the decade, including the severe recession of the early ‘90s. In 1990, manufacturing was still 18% of Upstate employment but had fallen to 9% Downstate, meaning Downstate’s transformation to a service-based economy had effectively been completed. After the recession was over, the Downstate area did grow more rapidly, but Upstate employment growth still gained over 200,000 jobs and had 7.4% growth over a seven-year period.

|

NYS EMPLOYMENT GROWTH, 1990-93-2000, NY AND REGIONS |

||||||

|

1990 |

1993 |

2000 |

1990-2000 |

1993-2000 |

||

|

NYS |

8203 |

7750 |

8624 |

5.10% |

11.30% |

|

|

Downstate |

5319 |

4941 |

5606 |

5.40% |

13.50% |

|

|

Upstate |

2884 |

2809 |

3018 |

4.60% |

7.40% |

|

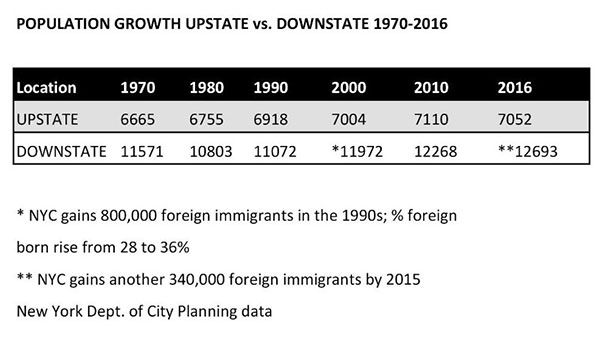

Foreign immigration, especially into New York City, began to make a major difference in population growth in the two regions in the 1990s. According to New York City Planning reports, the city gained 800,000 foreign immigrants in the ‘90s .This gain in the City, where two-thirds of the Downstate population lives, roughly mirrored the 800,000 person growth in population in that decade for the Downstate region. Between 2000 and 2015 the city gained another 340,000 foreign immigrants and Downstate gained another 425,000 persons. Between 1990 and 2016 Downstate gained more than 1.6 million people and more than 14% increase in population. Upstate New York gained only 2% in population. With population growth comes new demand for goods and services and employment gains.

By 2000 manufacturing employment was 14% of employment in Upstate New York and only 6% Downstate. The United States entered another recession in 2001 and employment actually declined for two years, including a loss of 2 million manufacturing jobs. The terrorist attack that destroyed the Twin Towers and killed thousands also had significant effects on employment in New York beyond the impact of the recession.

After the recession ended employment in the Downstate region grew rapidly until 2008. But the growth rates of the two regions differed sharply, with Upstate growing only 1.7% in the five years versus 6.1% in the Downstate region, when the Great Recession hit New York and the nation. New York City’s economy took off after the Recession, but Upstate New York had lost another 145,000 manufacturing jobs in the decade, more than a third of its remaining factory jobs from 2000. By 2010, Upstate New York had fewer jobs than it did in 2000.

The Upstate economy had a very bad ten years, from 2000 to 2010, and the manufacturing and other job losses during this period truly shook the base of the Upstate economy.

Employment

|

2000 |

2003 |

2008 |

2010 |

Growth 2003-2008 |

Growth 2000-2010 |

|||

|

NYS |

8624 |

8395 |

8777 |

8544 |

4.6% |

-0.9% |

||

|

Downstate |

5606 |

5434 |

5765 |

5622 |

6.1% |

0.3% |

||

|

Upstate |

3018 |

2961 |

3012 |

2922 |

1.7% |

-3.2% |

||

The past column reported that Upstate private sector economic growth from 2010 to 2016 was 5.8%, with slightly faster growth in the bigger metro areas like Albany, Buffalo, and Rochester, but weak-to-no growth in other areas. How and where the state government is allocating its resources and assets will be the subject of the next column, along with a continued look at its economic development policies and overall strategic efforts to leverage meaningful improvement in the Upstate economy.

[Read: Upstate is Home to Heavy Voter Turnout, Major State Investment and Minimal Job Growth]

(1) Older historical employment data contained different employment classification systems, that mixed proprietors and payroll together, among other differences, so the series used for 1980-1990, and for manufacturing from 1979 to 1990, is not comparable to a later 1990 base that uses only payroll employment coming forward from that time.

(2) The New York State Labor Department metro area employment data places Orange County in a Westchester-Rockland-Orange region, so Orange County is counted in Downstate employment.

***

Jim Brennan was a member of the New York State Assembly for 32 years, where he chaired four committees. On Twitter @JimBrennanNY.

***

Have an op-ed idea or submission for Gotham Gazette? Email This email address is being protected from spambots. You need JavaScript enabled to view it.

Trump Administration’s Edict to CDC Puts Millions of Lives at Risk

The Washington Post recently reported that, in an unprecedented and dangerous move, the Trump-Pence administration has banned the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) from using seven key words and phrases: “evidence-based,” “science-based,” “transgender,” “fetus,” “vulnerable,” “entitlement,” and “diversity.”

As a health care provider committed to fighting health disparities and caring for everyone who comes through our doors, we are horrified by these reports. This is dangerously ideological, and will put the health and well-being of millions at risk.

It’s not just about these seven terms. The Trump-Pence administration is trying to make a radical change in the focus of the entire agency—pushing a science- and evidence-based agency to one seeking to advance extreme ideology. The CDC is a non-partisan, non-ideological federal agency charged with scientific research and improving and protecting public health. This move is a direct contradiction to the pledge the agency has made to the American people.

This is just one more attempt by the Trump-Pence administration to prioritize a fact-free, ideological agenda over people’s health. From day one, this administration has shown a complete disdain for women, LGBTQ people, people of color, and science—from the policies they’ve enacted to the people they have put in charge of important programs. This effort further reveals their agenda: using the federal government to push harmful, politically driven policies at the expense of science and medicine.

This is only the latest of a long string of dangerous policies and rhetoric coming out of the Trump-Pence administration. Just a few weeks before this, Trump decided that reliable birth control methods should be replaced with the “calendar method,” which fails nearly a quarter of those who use it every year.

It’s clear that this administration is attempting to infiltrate all areas and agencies of government—and of our private lives—with their harmful ideologies. And it’s not just the administration. Under House Speaker Paul Ryan’s leadership, the House has worked tirelessly to restrict access to sex education, birth control, and abortion. In fact, when recently discussing the GOP tax cut plan, Speaker Ryan proclaimed that women need to have more babies.

The edict to the CDC is an affront to women, to transgender people, and to all communities that experience health disparities—this is an affront to the patients that we serve every day in New York City and elsewhere. It’s also an affront to the professionals who work at the CDC, to the science and medical communities whose work will be deeply affected, and to anyone who has benefited from scientific research or medicine in the United States and around the world.

The Trump administration is using the federal government to try and control women’s bodies and erase LGBTQ people and people of color. This goes directly against the will and values of New Yorkers—and of Americans—and we will not stand by and let this happen.

This move is beyond ideologically twisted, and will put millions of lives in danger, including our patients’. The Trump-Pence administration should be ashamed, and must end this dictate immediately.

***

Laura McQuade is President and CEO of Planned Parenthood of New York City.

***

Have an op-ed idea or submission for Gotham Gazette? Email This email address is being protected from spambots. You need JavaScript enabled to view it.