The Mayor’s Mission and the Mess at Rikers

Mayor Adams visits Rikers Island (photo: Michael Appleton/Mayoral Photography Office)

The U.S. criminal justice system is at a crossroads. After the killing of George Floyd, there were bipartisan calls to address the failures of a historically unequal justice system. Across the country, reform candidates won office for District Attorney, Judge, and Sheriff. But the pandemic era uptick in crime has brought backlash. The recent recall of San Francisco’s progressive prosecutor Chesa Boudin is upheld as evidence of the decline of American support for justice reform, and one indicator that elected officials should slow their support for reforms.

The reality is more complicated: Most Americans are both worried about crime and safety, and support criminal justice reform. This is true particularly for the communities of color who are disproportionately victims of crime and overrepresented in America’s jails and prisons.

In the words of New York City Mayor Eric Adams, “public safety and justice are the prerequisites to prosperity.. He is right – these concepts go hand in hand. Achieving both benefits everyone.

In New York City, little exemplifies that more than closing the irredeemable jails on Rikers Island.

Half of the people jailed at Rikers Island have a mental illness, including over 80% of women. 27 people jailed at Rikers have died in the past year and a half, and an improving but still profound staffing crisis has denied people access even to basic medical care. The dilapidated jails themselves provide the main source of weapons in the facilities. It is no wonder that people who spent time at Rikers have a higher rate of rearrest than similarly situated individuals; exposure to violence has real repercussions – for all of us.

This crisis is not new, but as Mayor Adams recognizes, addressing it could not be more urgent.

These considerations led to the decision to close Rikers in 2017. It was a realization made after heeding the calls of people who had been incarcerated at Rikers, families of those whose loved ones had died inside, people who worked there, and countless officials, including former Commissioners of Correction.

Transformation cannot occur on an island isolated from public transit, families, attorneys, and the courts. Nor would staying on Rikers make fiscal sense: trying to rebuild jails on the decaying landfill that makes up three-quarters of Rikers Island would cost significantly more and take far longer than the new system of borough facilities being built to replace Rikers and other existing jails.

Mayor Adams and Correction Commissioner Louis Molina have embraced the moral imperative to make change in the jails. The mayor has visited Rikers Island four times since taking office, reflecting this as a serious personal priority. Work is underway to demonstrate progress regarding staff absenteeism, violence, and broken cell doors.

The mayor and commissioner have also endorsed closing Rikers for good. They now have the historic opportunity to demonstrate that they can do both of these things – address the crisis at Rikers today, and execute on the mission to close it altogether. With a jail population and correctional staff that is over 90% Black and Latino, this is a matter of not just safety, but also of racial justice.

A key piece of the answer is ensuring that the new system of borough facilities is not limited by the de facto practice of U.S. correctional agencies, or vulnerable to the same failures. New York City can draw inspiration from international models such as Norway, places demonstrating that it is possible to have secure buildings that are humane and dignified while minimizing violence. Commissioner Tom Foley of the Department of Design and Construction has visited European facilities; there is reason to be heartened about the possibility for change.

A path to both safety and justice in New York also includes continuing to reduce the jail population. Since the high point of incarceration in New York City in the 1990s, the city has witnessed a significant decline in both the crime rate and the jail population, making it both the safest large city in the country and the one with the lowest rate of incarceration. We can build on and continue this legacy.

Almost 1,400 people have been at Rikers more than a year waiting to go to trial, keeping both them and victims in limbo waiting for resolution of their cases, including accountability and justice. Case processing reforms alone, some of which are underway, could reduce the jail population in New York City by well over a thousand people.

Sufficient funding for supportive housing (affordable housing and wrap-around services for people with serious mental illness and substance use disorders) and enhancing diversion programs like supervised release would cut waitlists, boost effectiveness, and increase safety. This would also give judges better options for people who lack stable housing, who often feel they lack safe alternatives to the streets or Rikers.

Stopping violence, and gun violence in particular, of course goes beyond Rikers Island. But there is no path to a safer New York City, and no path to a city that is more racially just and fair, that does not include ending the incubator of violence that is Rikers.

In the recent words of Mayor Adams, “If we get it right in New York City, it gets right across the whole country.” Now is the time to demonstrate that in New York City and nationally, justice and safety can go hand in hand. And on the urgent task of closing Rikers Island, safely reducing the jail population, and transforming the city’s jails, New Yorkers must support the mayor’s leadership in getting this done.

***

Dana Kaplan is senior adviser to the Independent Commission on New York City Criminal Justice and Incarceration Reform, is an Art for Justice Fund fellow and former deputy director of the Mayor’s Office of Criminal Justice.

***

Have an op-ed idea or submission for Gotham Gazette? Email This email address is being protected from spambots. You need JavaScript enabled to view it.

To Beat Extreme Heat, New York City Needs to Look to the Streets

Street heat (photo: Benjamin Kanter/Mayoral Photo Office)

It's summer in New York City, and the word on the street is heat – literally. Some of the hottest places are the pavement itself, including the city’s 6,300 miles of streets and highways. To more effectively address urban heat islands, New York City would benefit from a cohesive, science-based approach that studies how to best integrate existing and emerging technologies for cooling these surfaces.

Two recently proposed laws by the City Council would require cool pavement pilots by the Department of Transportation and Department of Parks/Department of Environmental Protection. Such studies would serve as an important piece of the puzzle, helping to address many key questions about the viability of urban heat island mitigation approaches in New York City. This includes issues not only directly related to heat reduction, but also matters of safety, durability, longevity and maintenance.

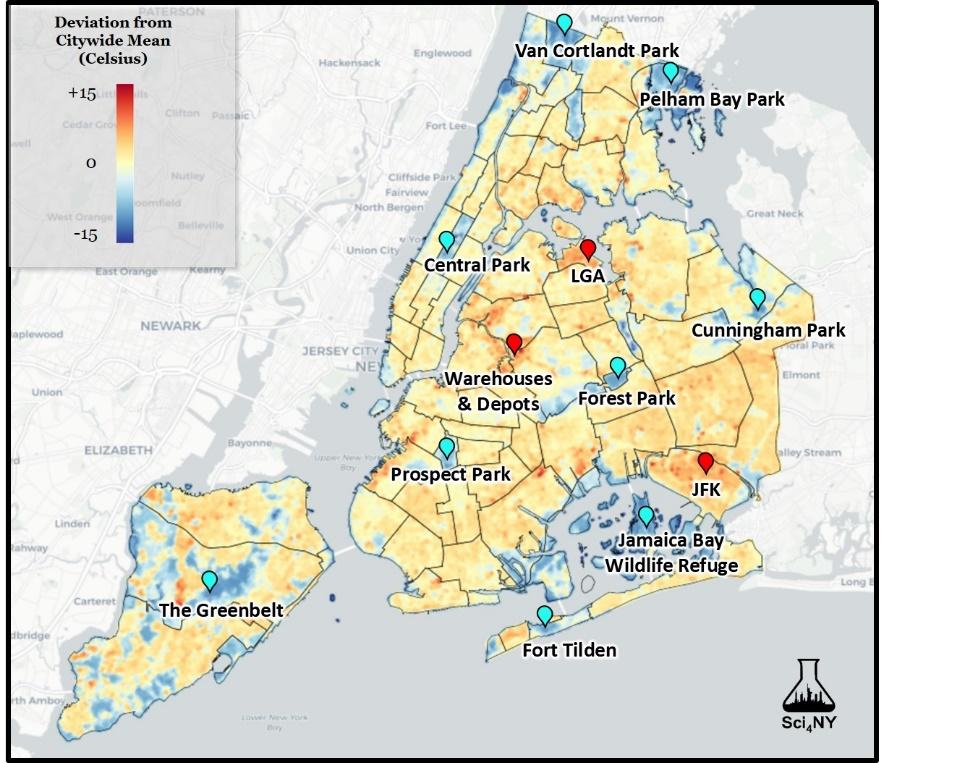

Our recent analysis using Landsat 8 satellite data from the past five summers (2017-2021) highlights the importance of including pavement in New York City’s extreme heat equation. The image above shows how much the temperature deviates at a given location compared to the citywide average.

Some of the hottest areas easily visible by eye on the map are largely covered in pavement, including JFK and LaGuardia Airports. While it’s challenging to see the individual streets and sidewalks here, we know they are made of the same types of materials that amplify the urban heat island. Environmental justice areas are disproportionately affected by heat due to their relatively high ratios of paved areas to greenspaces. As a result, they are particularly relevant to consider in this context.

In terms of absolute temperature, paved areas can reach 120 - 150 ⁰F. This is due to the fact that many of these surfaces are composed of asphalt, which is very effective at both absorbing (due to its dark color) and retaining heat. While less often discussed, heat retention by pavement can also adversely affect human health at night by reducing people’s ability to recover during heat waves.

The coolest areas easily visible on the map are largely greenspaces, where tree cover and lack of pavement work in tandem throughout the day to limit heat absorption and retention. While we should expand greenspace and green roofs as much as possible, we should think of these options as parts of a system. Additional heat-reduction benefits can be achieved if thoughtfully coupled with attempts to cool our pavement. Furthermore, in areas where we can’t realistically expand our greenspace, addressing street heat takes on increased importance.

One option for consideration is to reduce the solar reflectance of pavement, commonly referred to as cool pavement. These applied coatings reflect up to 30-50% of incoming solar energy, compared to 5-20% for untreated asphalt depending on its age. In a one-year pilot in Phoenix, Arizona in 2020, streets treated with cool pavement showed average surface temperatures 10.5-12.0⁰F lower than standard asphalt during peak afternoon hours. Temperatures below the surface also averaged 4.8⁰F lower on the cool pavement. When planned carefully, such reductions in temperature not only limit urban heat islands directly, but can also reduce cooling needs of nearby buildings.

Los Angeles has undertaken its own ambitious efforts to reduce urban heat under the Cool LA program. By 2028, it plans to cover 250 lane-miles of city roads. One challenge they’ve encountered is that reflective pavement coatings can raise localized air temperatures, increasing the heat experienced by people using these surfaces. As a result, these coatings have been used more frequently to date on roofs or parking lots. For locally affected buildings, which may absorb heat from treated pavement, reflective coatings on their exteriors can minimize these effects.

These issues do not mean that cool pavement technology is unworkable in cities like New York. Rather, they indicate that it needs to be done thoughtfully, taking into account human health and equity concerns, as well as optimizing interactions with the local built infrastructure. In fact, LA is pressing ahead with its program due to the core need to address urban heat as temperatures rise, working with researchers to address these challenges. New York City can and should do the same evaluations, starting with the recently proposed cool pavement pilots.

While increasing the reflectance of pavement gets the most attention, there are a handful of newer, related cool pavement technology options that may be useful for New York City to consider as well. There are also lots of other cool ideas currently available or in the works, including using the energy from pavements to heat buildings. Others focus on engineering a host of “super-cool” materials to increase the ability of structures to reflect and/or emit heat.

Finding the best ways to evaluate and apply all of this information will take expertise. Fortunately, a program already exists in New York City. Town + Gown (T +G) – a citywide research program within the Department of Design and Construction (DDC) – works to draw from knowledge in New York City’s academic institutions and practitioner city agencies to address challenges in the built environment.

Such efforts can help evaluate how and where cool pavement might be successfully integrated into New York City’s street designs, carefully weighing the multiple uses and maintenance considerations this important infrastructure system must meet. For example, there is already work underway in New York City on permeable/porous pavements, which can help address stormwater management issues and also reduce the urban heat island.

In the conversation about urban heat, the trees overshadow the conversation. While they’re a key part of the equation, we need to branch out and give the streets more attention. With a bit of careful planning and scientific input, we may be able to make New York City an even cooler place.

***

Yosif Zaki is a graduate student with expertise in data analytics at the Mt. Sinai School of Medicine. He is also a volunteer for Science for New York (Sci4NY), an effort to have policymakers and scientists in NYC work together to address key challenges facing the City. Nancy Holt, PhD, leads Sci4NY. She holds a PhD in Physical Chemistry and formerly worked on climate change issues at the U.S. Department of State. On Twitter @Sci4NY.

***

Have an op-ed idea or submission for Gotham Gazette? Email This email address is being protected from spambots. You need JavaScript enabled to view it.

Build a Workforce Pipeline for New Yorkers with Disabilities

Mayor Adams visits the Mayor's Office for People with Disabilities (photo: @NYCDisabilities)

New York City has an historic opportunity to engage people with disabilities more fully in the workforce. With nearly 1 million New Yorkers living with a disability, seizing the opportunity should be a top priority. It’s time to build a pipeline to address the needs of employers and New Yorkers with disabilities.

The opportunity stems from three simultaneous dynamics: a low unemployment rate nationally; a high unemployment rate for people with disabilities in New York City; and more flexible working arrangements as a result of the remote working necessitated by the COVID-19 pandemic.

According to a recent report by Center for an Urban Future, nearly 17% of New Yorkers of working age with a disability were unemployed in 2021 – up from 7.4% in 2019. “This disastrously high unemployment rate has persisted for much of the past two years,” the report states, “even as the unemployment rate for New Yorkers without a disability has fallen sharply since the summer of 2020.”

New York City’s unemployment rate was 6.2% in June. The U.S. unemployment rate was even lower at 3.6% in June. Job openings nationally totaled 11.3 million at the end of May.

The growing demand for workers, coupled with more flexible working conditions, creates a fertile environment. But preparing people with disabilities to meet the demand often requires training – and, in the case of high-school-age youth – pre-training.

We know that reality well, as we run a nonprofit organization, the Institute for Career Development (ICD), that trains and pre-trains people with disabilities in New York City for career opportunities.

The training covers a broad range of jobs in such areas as building repair, custodial services, human services, retail, and information technology. ICD’s IT Academy, for instance, offers the first fully-accessible certification-based technology training programs for New Yorkers with disabilities.

The challenge, however, is that public investments in career development for people with disabilities are declining even as the opportunity grows. As the report by Center for an Urban Future reveals, New York City funding for programs serving New Yorkers with intellectual and developmental disabilities has plunged 82% over the past two decades, from $70.7 million to $12.6 million.

What New York City needs is a robust pipeline to expand the number of individuals with disabilities in the workforce. That pipeline should have three key components.

First, it should provide specific funding to support the training and pre-training of individuals with disabilities. That funding needs to be earmarked specifically for people with disabilities. Too often workforce training funds include people with disabilities but never actually reach them.

Pre-training is needed to support youth who might otherwise fall through the cracks between schooling and career development. Research recently conducted for the Institute for Career Development by the nonprofit consulting firm The Bridgespan Group identified a significant gap in serving people with disabilities in New York City. That gap is in the transition from school to career, during which school-based support ends and career opportunities – as distinct from job opportunities – have not yet arisen. Filling that gap through pre-training would substantially enhance career opportunities earlier in life.

Second, the pipeline should fund apprenticeships for individuals with disabilities. All too often, interested potential employers have doubts about how well people with disabilities will fit into their work environment. The best way to remove those doubts is to give people with disabilities an opportunity to prove themselves. Let potential employers see for themselves how effectively individuals with disabilities can fulfill the specific job responsibilities required.

It’s especially appropriate to maximize opportunities for people with disabilities at a time when the work environment has adopted the more flexible working conditions – due to the COVID-19 pandemic – that people with disabilities have long advocated. For years, people with disabilities urged greater corporate consideration of work-life balance – with allowances to address family needs or visit a doctor during the day. In the wake of the pandemic, such considerations are now standard practice. It’s only right that people with disabilities should benefit from them as well.

Third, the pipeline should incentivize the hiring of individuals with disabilities. Incentives such as tax benefits for employers or public employment goals should provide the extra push to get employers to embrace the potential of New Yorkers with disabilities.

The federal government, for instance, has a 7% goal for hiring individuals with disabilities. The City of New York should provide incentives to underscore its commitment as well.

The New York City workforce would benefit greatly from fuller engagement of people with disabilities. It’s time for New York City to build the pipeline needed to transport that human energy so that it can revitalize the economy as well as the lives of New Yorkers with disabilities.

***

Diosdado G. Gica and Joseph T. McDonald III are Co-Presidents of the Institute for Career Development, based in New York City.

***

Have an op-ed idea or submission for Gotham Gazette? Email This email address is being protected from spambots. You need JavaScript enabled to view it.