High Hopes for New Era of MTA Transparency

Subway riders (photo: Marc A. Hermann / MTA)

In October 2021, Governor Kathy Hochul signed the Metropolitan Transportation Authority (MTA) Open Data Act, sponsored by Senator Leroy Comrie and Assemblymember Robert Carroll. Hochul said the law will require MTA data to be “properly available for constituents to read and utilize. New Yorkers should be informed about the work the government does for them every day, but we have to make it easier for them to get that information."

The new MTA law is the first open data law passed by New York State and was championed by Reinvent Albany with the support of more than a dozen advocacy organizations. The law is now being implemented by the MTA, a state authority that runs the New York City subways and buses as well as the commuter railroads.

The MTA currently has a $18.5 billion annual operating budget, and is the largest public transit authority in the United States. Before COVID-19 hit, it served 5.5 million daily riders on the subways alone, and millions more on the buses and railroads. It is currently undertaking the largest capital plan in its history, with $55 billion in planned spending on infrastructure. Given the MTA's importance to the region's economy, the authority's operations and spending are of great importance to policymakers, riders, and all New Yorkers. One way to pull back the curtain on how the MTA is doing its job is through greater transparency.

Efforts to increase transparency at the MTA are not new. A decade ago, at the urging of advocates and riders, the MTA began releasing real-time service data as open data to the public via third-party apps like Google. The MTA has since created numerous performance and capital program dashboards, but there is much work to do to consolidate the underlying, raw data and ensure it is updated automatically on the state’s open data portal. The state’s portal provides tabular public data – essentially spreadsheets, mapping data, and other types of data – from the various state agencies and authorities in one place, allowing journalists, advocates, and the broader public easy access to state government data.

This week is Open Data Week, and next week is Sunshine Week. Fortunately, this time around we are optimistic about the future of MTA open data because of the new state law and what the government and the public have learned during the COVID-19 pandemic about the value of transparency.

Now, the MTA can let the open data sun shine on three high-profile and timely concerns: daily ridership numbers and projections for the future as the MTA emerges from the COVID-19 pandemic; the upcoming congestion pricing environmental assessment; and the release of its 20-year needs assessment in 2023.

What Does the MTA Open Data Law Require?

The MTA Open Data Law codifies for the MTA the requirements of Governor Cuomo’s Executive Order 95 of 2013, the state’s Open Data EO that established data.ny.gov. The bill defines what is publishable data and requires the MTA to designate a data coordinator to oversee agency’s compliance.

Under the law, within 180 days – in April 2022 – the MTA must create a catalog of public datasets and a schedule for release of this data within three years. The schedule and catalog will be provided to the Legislature and the public.

What Has the MTA Done So Far?

In October 2021, the same time that the MTA Open Data Law was signed, Governor Hochul asked each agency to produce a Transparency Plan regarding their efforts to increase transparency and release more information to the public, including as open data. The MTA’s transparency plan includes a detailed description of how they will implement the MTA Open Data Law, including deadlines for publishing more data on the state’s open data portal.

The transparency plan also notes that the MTA can reduce its Freedom of Information Law (FOIL) load and costs of producing records by uploading more data to the open data portal. The MTA recently offloaded requests for police incident reports from their FOIL requests into a separate electronic portal. This action was in part spurred by Reinvent Albany’s finding in our Open MTA report that two-thirds, or nearly 6,000, of the MTA’s 9,000 annual FOIL requests were for police incident reports.

Sarah Meyer, the MTA Chief Customer Officer who first came on with Andy Byford at New York City Transit, has been designated as the data coordinator, and will lead the agency’s effort.

The MTA has grown the number of its datasets on the open data portal from 76 to 100 as of March 9, 2022, and intends to publish a number of other datasets in the short term. The MTA’s plans are also detailed on a new website that outlines its efforts to comply with the law, which includes the following timeline:

This timeline importantly includes that the MTA will “automate data updates” – this means that data will not need to be manually uploaded each time there is an update. This is crucial for the sustainability of the MTA’s open data and transparency efforts because automating data release will reduce staff time and ensure it is the most useful to the public.

Opportunities for New Open Data Releases

The MTA’s transparency plan has prioritized getting MTA data that is already published in PDFs up on the open data portal, including data from the MTA Board Books and financial plans, which is an excellent first step. However, there is a wealth of data – including raw data – that is not currently published as open data that is of great interest to the public.

Additionally, when the MTA announces major new initiatives or releases new reports, these are important opportunities for the agency to think ahead about what data should be released as open data.

We recommend that the MTA specifically integrate open data into three upcoming or timely initiatives:

1. Ridership Projections

The MTA’s daily ridership numbers are important markers for policymakers and New York City boosters given the massive decline in ridership that the MTA experienced during COVID-19. The resulting economic fallout from the depressed ridership necessitated billions of dollars in federal aid to keep the agency from going bankrupt.

At first, the agency released daily ridership numbers only via press releases or upon request. In response to requests from advocates, the MTA now has a website dedicated to its daily ridership numbers. A spreadsheet of the data since March 2020 is available, comparing daily ridership to pre-pandemic days in 2019. However, this is not currently on the state open data portal.

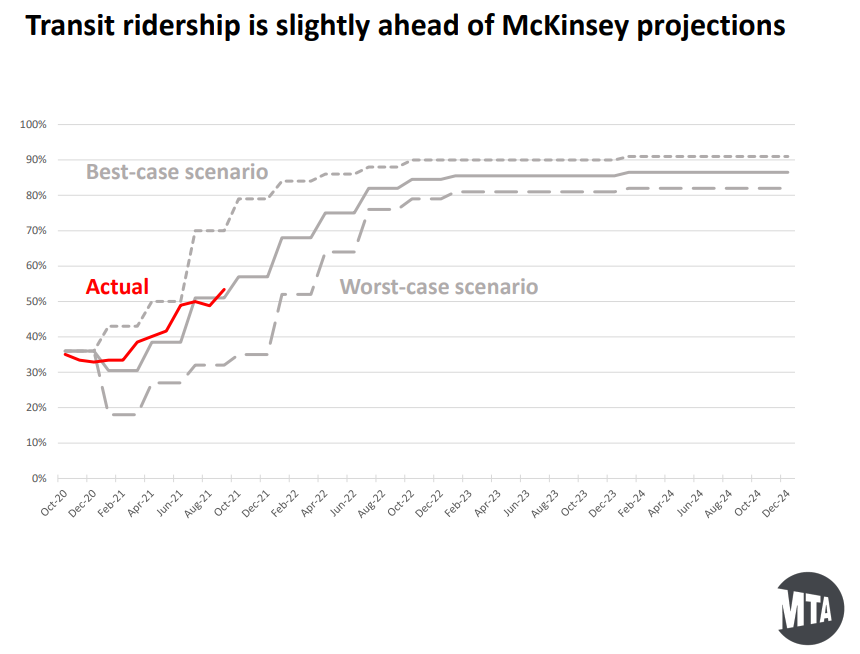

Additionally, the MTA in July 2020 began using McKinsey, a consulting firm, to project ridership numbers to help show the revenue impact of depressed ridership on the agency as it was seeking federal aid. The McKinsey ridership projections have also been used in developing the MTA’s financial plans. However, future ridership projections have not been released in open data, and have only been shared by the MTA in chart form. The chart below was published by the MTA in October 2021 as part of its board meeting presentation.

The MTA has said that it intends to hire a new consultant to produce updated ridership projections. As part of its contract, it should ensure that the raw data for the projections is released in an open data format. This way, policymakers, journalists, and advocates will have access to the data to compare ridership with the projections and better understand the MTA’s future.

2. Congestion Pricing Environmental Assessment

The MTA is in the process of conducting an environmental review of its congestion pricing program (called Central Business District or CBD Tolling by the MTA), which is currently slated to start in January 2023 after a two-year delay.

Congestion pricing has been strongly supported by transit and environmental advocates because it will raise $15 billion for the MTA’s 2020-2024 capital program and reduce traffic congestion. This is the single largest funding source for the latest capital program, and will fund critical improvements to MTA subways, buses, and commuter rails.

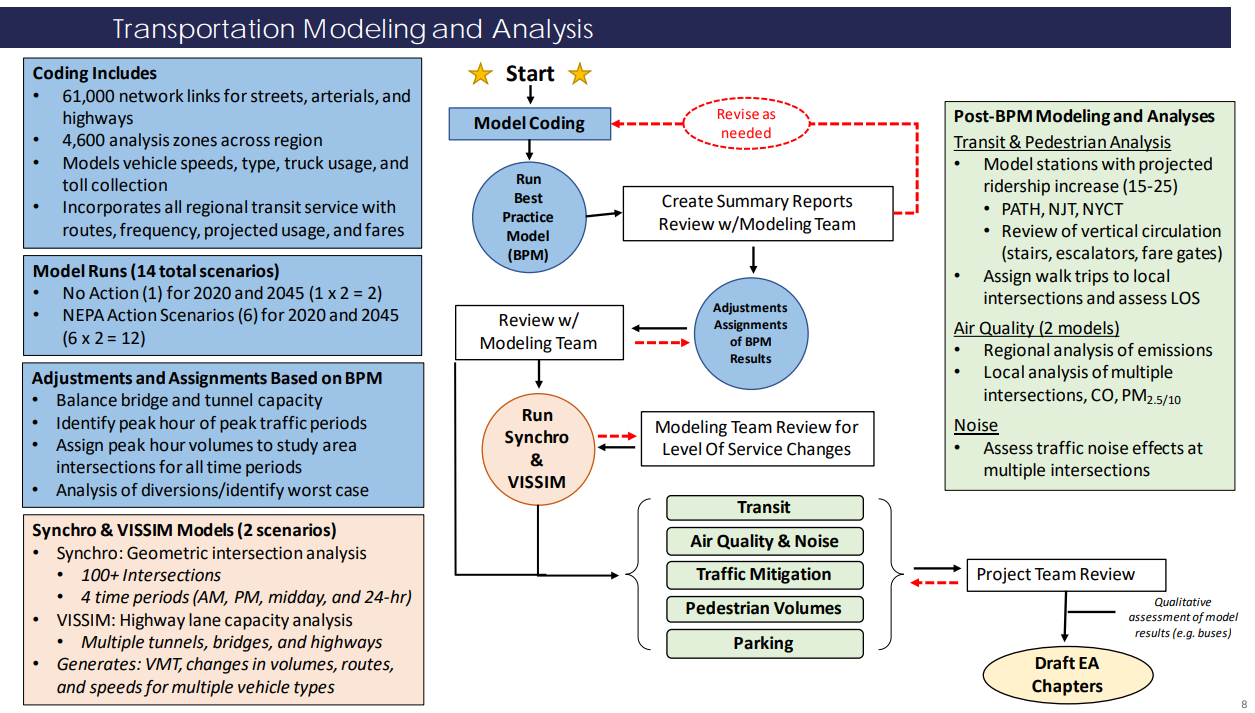

The MTA is expected to release its draft Environmental Assessment (EA), as required by the federal government, in May 2022 (see the program adoption timeline here). The EA will include a large amount of transportation modeling and analysis, with 14 different scenarios (“model runs”). These will show how different pricing structures, time of day pricing, and discounts and/or toll credits will affect traffic in the region and the effectiveness of the program – including how much money will be generated to fund the MTA capital program.

By law, the program must raise $1 billion annually to support $15 billion in capital bonds. A slide about the modeling and data that is expected to be generated is below, from a September 2021 staff presentation to the MTA Board.

The results of this type of data modeling are typically released as appendices of large PDFs that can be hundreds of pages (a traffic appendix for the now paused LaGuardia Airport Transit Access EIS numbered 353 pages for Part 1, and 300 pages for Part 2). The MTA can and should do better.

Open data on congestion pricing will help advocates help the MTA. If the MTA releases its traffic modeling data in an open data format, this lets the advocates and journalists have easy access to the information that will make the case for congestion pricing, and support the MTA’s efforts.

3. 20-Year Needs Assessment

Before the release of its draft five-year capital program, the MTA has released updates to its 20-year needs assessment, which provide the basis for determining the capital needs of the MTA based on regional population and ridership trends as well as the state of its existing infrastructure and assets.

Unfortunately, the MTA declined to publicly release a needs assessment before the adoption of its largest ever $55 billion 2020-2024 capital program, which is the only capital plan in the MTA’s history to not have an accompanying needs assessment released (only one other time, in 2000, was the needs assessment not released before capital plan adoption, but it was released soon after).

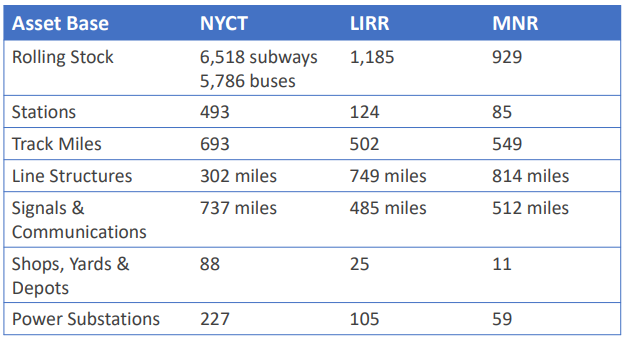

The MTA is now required by law to release its next 20-year needs assessment in 2023, which will be ahead of the adoption of its 2025-2029 capital plan. MTA staff recently presented plans for the assessment’s release. See the graph of some of the broad data on MTA assets that was included in this presentation.

Ahead of the September 2023 release, the MTA should ensure that all the data contained in the assessment is prepared in an open data format. This will help researchers and oversight entities better match the MTA’s assessment of its needs with its capital spending to ensure that the right investments are being made.

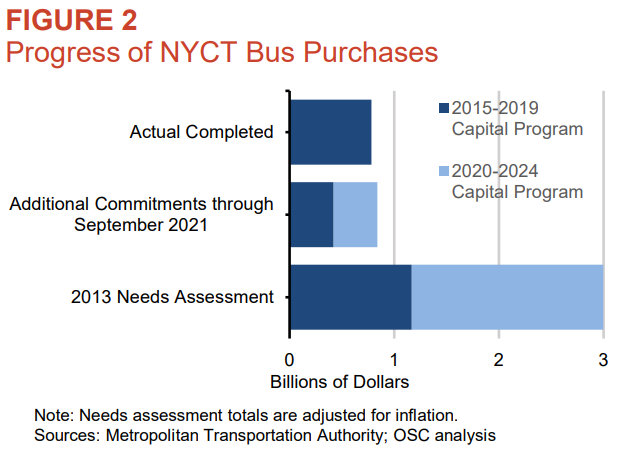

The State Comptroller in December 2021 conducted exactly this type of analysis, matching up the MTA’s capital spending on its 2015-2019 and 2020-2024 capital program with the 20-year needs assessment that was released in 2013, which included projected needs from 2015 to 2034.

See the chart of the comptroller's analysis of the progress made on bus purchases. The analysis shows that spending and commitments to date are below the actual need.

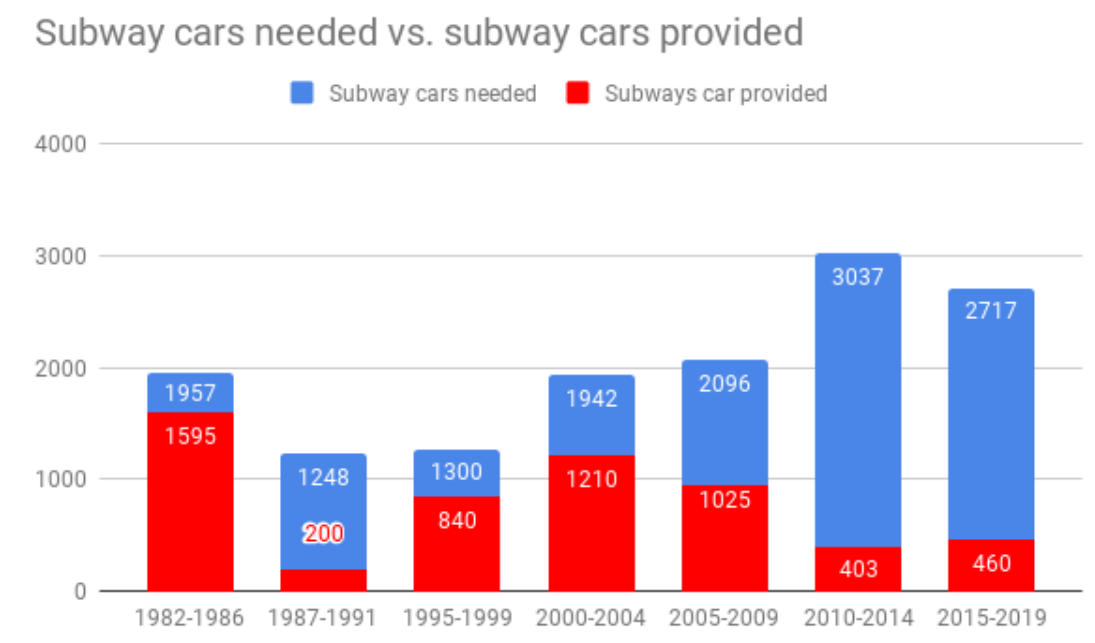

Reinvent Albany previously conducted an analysis of subway cars needed versus those purchased, building off of research by the Citizens Budget Commission. We found a similar lack of investment in subway cars compared to the stated needs, as seen in the accompanying chart.

Having the data to be able to match up the MTA’s needs with its spending is crucial for the accountability of billions in capital spending. Beyond the need for new buses and subway cars, there are large new needs related to resilience and climate change, as seen with the flooding in 2021 during Hurricane Ida and other storms. It is expected that the 2023 needs assessment will include a specific assessment related to resilience.

These three sets of data are just some of the information that the MTA should look to release as open data in the days and months to come. With an annual operating budget of $18.5 billion, the MTA generates a lot of public data that can and should be released to help shine a light on its operations.

***

Rachael Fauss is the Senior Research Analyst for Reinvent Albany, a government watchdog organization. On Twitter @RachaelFauss & @ReinventAlbany.

***

Rachael Fauss is Senior Policy Analyst at Reinvent Albany. On Twitter @RachaelFauss & @ReinventAlbany.

***

Have an op-ed idea or submission for Gotham Gazette? Email This email address is being protected from spambots. You need JavaScript enabled to view it.

Thinking of Moving Out of New York City? Some Cautionary Words

Movie in the park (photo: @NYCParks)

First of all, full disclosure. My wife and I have owned a home near Woodstock, NY for years. My wife was brought up surrounded by nature in Pennsylvania and thrives on feeding birds and chipmunks, and I was born on 50th Street and 8th Avenue and am energized by street life, asphalt, and the A train. We live in the West Village, and have for many years, including through the pandemic.

As has been well-publicized, a slew of New Yorkers, no longer bound by having to go into the office full-time or at all, have been gravitating to living in the Hudson Valley, the Hamptons, the Berkshires, and elsewhere. While many are moving back, many others are surely still considering a move out of the five boroughs for greener pastures. But if you move from the city, here’s what you’re going to be missing. You’ve been warned.

1) You’ll Be Walking A Lot Less

Living in the city is to love to walk and wander through its streets, its neighborhoods, its history and character. On a walk in Chinatown, one sees plaques of where writers were born and where historical documents were signed, and ends up on Doyers or Pell Street for delicious dim sum. In the suburbs, you won’t be walking anymore -- and if you do, it has to be planned, a drive to a hike. The main reason you won’t is in most of these locales, there are no sidewalks or shoulders on the road. If you walk, you could die. And because you’ll be driving everywhere, you’re going to be gaining weight and feeling lifeless. New Yorkers (of the five boroughs) weigh eight pounds less than the average American because they often walk miles daily, without even thinking about it.

2) Say Goodbye to Bodegas

In virtually every neighborhood in the city, whether Windsor Park or the East Village, there’s a bodega or small deli, oftentimes several, that has all of the basics you need, from ice cream to toilet paper. There’ll be no more bodegas in the suburbs or country-side. Now you’ll be driving to a supermarket and wandering the giant aisles where bagels and lox are considered foreign foods.

3) Every Street in the City Carries Memories

The East Village is where you used to drink egg creams at Gem Spa, the Upper West Side is where you made stops at Zabar’s, and DUMBO is where you went for pizza at Grimaldi’s. Or whatever your versions of this as a city traveler. Each neighborhood has its own aura, feeling, and joie de vivre. But upstate, it doesn’t work that way. Kingston is a small city, with a street called Broadway, filled with gas stations and Chinese take-out joints. A nice place for a weekend getaway.

4) The Suburbs Sleep

New York City’s subway runs 24/7, many pharmacies are open all night, and you can get a sit-down dinner at midnight with ease. That won’t be happening in the Hamptons or Berkshires. Some Berkshire restaurants have their final call at 8 p.m., and some stay open later, until 9 p.m. At 10 p.m., most everything is closed.

5) Whom You’ll Be Meeting

In New York City, I have friends who were originally from Davenport, Iowa, Allentown, PA, Nigeria, Kenya, and Australia. Upstate and in the Hamptons, you’ll be meeting, almost exclusively, ex-New Yorkers. And most of them will simply tell you over and over again how overjoyed they are to have left a crowded, dirty city.

6) Nature Can Be Tough

While nature is not the prevailing value that New York City offers, there is plenty of it in the five boroughs and worth exploring if you haven’t. The coyotes who have roamed the West Side Highway, the owls in Central Park, and the falcon who nests off of Washington Square are all New Yorkers. But in the Hudson Valley, the 600-pound bears will eat your birdseed, turn over your garbage cans, and hide in the woods when you’re barbecuing then try to steal your steak and burgers. And did I mention the ticks that cause Lyme disease? They’re everywhere. You’ve been warned.

7) Watch Out for the Drivers

On local roads upstate, in the Hamptons and Berkshires, drivers speed. They know every twist and turn, and tend to drive 50+ on a 30-miles-per-hour road. Moreover, they often don’t make full stops at stop signs because they’re in a rush, likely for ice cream at Stewart’s because there are no bodegas in walking distance.

8) Hamlets are Hamlets

In the town of Woodstock, which has about 7,000 or so residents, many people know one another and travel in similar circles and track each other’s movements. They know the people who own the local health food store, where they spend their winter, and what their children are up to. Everyone knows each other’s business. In the city of New York, with 8.8 million people, only your close friends know about you, and the remainder of the city’s denizens pays no attention to you and let you live your life gossip-free.

9) Adjust Your Sensibility

In the city, if you’re looking for a cup of coffee and there are five or six people on line, you’re not going to wait. You’re going to walk 65 steps and find the next coffee spot. In the Hamptons, Berkshires, and Upstate, you’ll wait. If you walk 65 steps, you won’t find another cup, you’ll find a parking lot.

10) You’re Giving Up Proximity

Most things in New York revolve around proximity. You get to know your neighbors in your building, the bodega owner and workers, and others in your community. You can walk to do many things and you can get public transit to do everything else. Anything you could want to do, from a museum to a show to a baseball game to a hike to a continuing education class to shopping to you name it, is not far off. If you live in a house upstate as most people do, often in the woods, with no neighbors around, proximity won’t operate. You’re on your own but for a lengthy drive.

***

Gary Stern is a New Yorker.

***

Have an op-ed idea or submission for Gotham Gazette? Email This email address is being protected from spambots. You need JavaScript enabled to view it.

As New York’s Next Building Boom Approaches, It’s Time to Double Down on Construction Safety

Construction workers (photo: Michael Appleton/Mayoral Photography Office)

One look at the New York City skyline and you know that tens of thousands of workers have made their mark on this city. Ironworkers, carpenters, welders, plumbers, and electricians, among countless other tradespeople built New York – and they’ll also be the ones who ensure New York’s future is just as bright as its past.

Construction, however, is undoubtedly dangerous work, and without proper safeguards and legal protections, the work becomes that much more perilous. That’s why the unionized construction industry has dedicated itself to ensuring that safety is paramount at every New York construction site, and that the rigorous safety protocols required on union job sites become the expectation at non-union job sites as well.

A recent report by the New York Committee for Occupational Safety and Health (NYCOSH) is particularly alarming – it shows worker deaths in New York City and State leading the national average. This was the case even in 2020, when most construction activity was stalled as job sites were paused early in the pandemic. Construction workers made up 21% of the national average of all worksite deaths in 2020, while in New York State, 24% of worksite deaths involved a construction worker.

The numbers are particularly stark when you compare union and non-union worksites. In 2020, 79% of workers who died on private worksites were non-union, which is tragic, but unfortunately not surprising. Far too many non-unionized construction sites across New York flout safety protocols for the sake of profit, and these workers, many of whom are immigrants and people of color, fear retribution for speaking out about safety concerns – leaving dangerous and often deadly safety issues unaddressed. This is unacceptable. No worker, regardless of union affiliation, should needlessly lose their life and no family should have to grieve and suffer as a result.

So, what needs to be done to buck this alarming trend and ensure New York’s construction workforce can earn a good living and be safe on the job?

Let’s start with unionization. Joining a construction union is the number one way to protect oneself and one’s livelihood in this business. With mandatory training, robust and rigorous safety protocols, and a clear chain of command on jobsites, contractors have much less ability to set unrealistic and unmeetable demands that can and too often result in tragedy.

Increasing New York City Department of Building (DOB) inspections and ensuring adequate funding is a critical step, too. If all safety measures are being followed on a jobsite, workers, forepeople, and site owners have nothing to be concerned about. DOB is not out to harm the industry. These types of agencies keep us all safe, and those of us in labor support and appreciate their hard work and are committed to continuing to work with them to ensure essential safety protocols govern all construction sites.

By increasing New York State Department of Labor enforcement, we can further bolster worker protections and ensure worksites are safe. I am grateful Governor Hochul included an additional $12.4 million specifically for worker protections in her executive budget proposal. It’s a critical step forward that should be included in the adopted budget.

We must ensure that laws that deal with the worst-case scenarios, such as a worker fatality or serious injury, remain intact. This includes the Scaffold Safety Law, which requires that all safety measures are taken by the contractor and site owner and that functioning safety equipment is provided. This law is a critical protection for workers and keeps worksites and contractors accountable.

New York’s construction industry is an economic engine that powers New York, and it’ll also be the industry that leads the state’s and city’s economic revival, particularly with the significant investment generated by the federal infrastructure bill and Governor Hochul’s capital plan. As the construction industry continues to build back New York, it’s critical that there’s a renewed commitment to safety at all worksites. Laws designed to protect workers do not inhibit construction and investment – instead they’re the foundation that will enable us to make New York stronger and better than ever.

***

Gary LaBarbera is the President of both the New York State Building and Construction Trades Council and the Building and Construction Trades Council of Greater New York. On Twitter @NYCBldgTrades.

***

Have an op-ed idea or submission for Gotham Gazette? Email This email address is being protected from spambots. You need JavaScript enabled to view it.