New York Needs a City Plan! ‘Planning Together’ Misses the Mark

New Yorkers participating (photo: Benjamin Kanter/Mayoral Photo Office)

On February 23, public hearings began for City Council Speaker Corey Johnson’s “Planning Together” legislation, which would institute a process for creating a comprehensive plan for New York City. I fully support city planning, but believe Planning Together’s top-down approach needs fundamental change.

New York City is virtually the only major city in this country that does not have a comprehensive city plan. Instead, we rely on a piecemeal approach to zoning that has resulted in an explosion of luxury towers without anywhere near adequate gains in real affordable housing.

Our siloed zoning approach has allowed inequity to flourish. Black and brown neighborhoods have shouldered the lion's share of new real estate development, which has led to rampant gentrification and displacement.

Arguably, the most urgent reason to adopt a city plan is the climate crisis. Considering that by the year 2100 daily high tides will flood many coastal neighborhoods, it’s hard to imagine that we can combat the climate crisis without a comprehensive plan.

For these reasons and more, it’s clear we need a city plan, yet Planning Together has several fundamental flaws. The most urgent flaw of this legislation is its top-down approach — it misses the opportunity to give the people more power in determining a just and equitable future.

In the first year of each 10-year planning cycle, every community board submits a district needs statement. In the second year, the city creates a “conditions of the city” report based on 13 categories. The categories of assessment will please many planners and organizers, as it includes a “displacement risk index” and a “segregation assessment.”

City leaders who point to these first two years as evidence of community buy-in are missing one crucial point — there is no formal requirement in the legislation to act on the information gathered from the first two years. We don’t just need more information, we need action. Without requiring interventions, it’s easy to see how real estate interests could corrupt the process.

In the third year of the planning cycle, the Office of Long Term Planning and Sustainability (OLTPS) would create three plans per district and present them to community boards and borough presidents. Let that sink in: Planning Together places the responsibility of community planning with an unelected mayoral agency instead of with the communities themselves. Community members are closest to both the unique problems and the most viable solutions in any given neighborhood. Any comprehensive planning legislation should recognize this and take a true bottom-up approach.

There are several changes to the legislation and related issues that should be made to ensure communities can fully engage in planning:

First, fully fund community boards. Currently, the combined budget of all community boards is a meager .02% of the total city budget. This lack of funding poses a major impediment to boards that may otherwise consider engaging in community planning.

Second, adequately staff community boards. Volunteer board members with full-time jobs and/or household duties cannot be expected to create a community plan. All boards should be appropriately staffed and include full-time urban planners.

Third, ensure community plans that are created have teeth and get implemented. Section 197a of the city charter allows community boards to create plans to guide development in their district. Yet, under our current system, community planning is often an exercise in futility; boards sometimes take years to compose a plan only for the city to ignore or reject it. Even when a plan is approved, implementation is not guaranteed. We cannot allow a mayoral agency to override community plans when they are created.

In Planning Together, after the OLTPS creates land use scenarios, community boards and borough presidents vote on which plan they like best. Unfortunately, these votes are in an advisory capacity. The city can move forward with whichever plan it chooses, regardless of the community decision. This (im)balance of power needs to be radically shifted to give communities the central voice in the process.

After the community board and borough president response, the City Council deliberates. Yet the balance of power between the legislative and executive branches is skewed as well. The legislation states: “if the Council failed to adopt a preferred scenario, OLTPS would choose a scenario and describe how such selection was made.” City Council members are much closer to communities than the OLTPS, so transferring power from the legislative branch to an executive agency takes away essential accountability.

Throughout the 10-year cycle, Planning Together lacks a comprehensive framework around public engagement. Our current system is entirely insufficient in ensuring community voices are heard. Case in point: the public hearing for Planning Together itself.

The meeting started at 10 a.m. on a Tuesday, when many New Yorkers were working. City officials were placed at the top of the agenda, and it took nearly five hours before testimony from other New Yorkers began. By the time public testimony began, many government officials had left the meeting. To make a comment, you had to sign up in advance, creating another barrier to entry for many citizens. Testimony was kept to a strict two-minute time frame. These factors prevented the opportunity for real dialogue

City planning is essential, and it is clear we cannot continue our current approach. Yet if we are truly to build the just and equitable city that works for all, New Yorkers need the central voice. Involving New Yorkers without becoming paralyzed by not-in-my-backyard (NIMBY) forces is not an easy balance to strike. Yet, we cannot allow our fear of NIMBYism to justify a top-down approach. I urge the City Council to radically amend this plan to ensure greater community control.

***

Aleda Gagarin is a City Council candidate for District 29 in Queens, which covers Forest Hills, Kew Gardens, Rego Park and Richmond Hill, with a Master’s in Urban Planning from CUNY-Hunter College. On Twitter @AledaGagarin.

***

Have an op-ed idea or submission for Gotham Gazette? Email This email address is being protected from spambots. You need JavaScript enabled to view it.

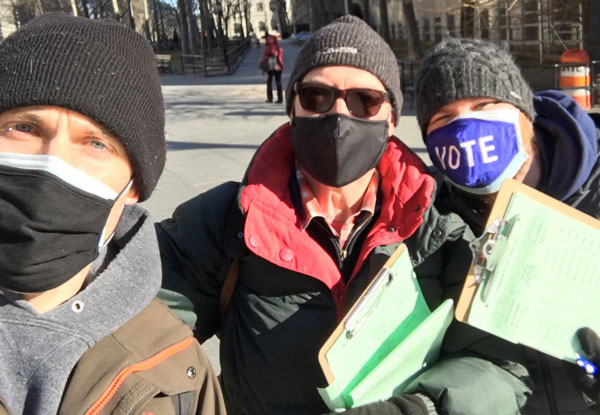

Safely Getting Signatures in a Pandemic?

Volunteers petitioning (photo: @INDBrooklyn)

Today — Tuesday, March 2, 2021 — thousands of people are taking to the streets across the five boroughs. Armed with facemasks, gloves, hand sanitizer, more pens than you can imagine, and stacks of inconveniently-long papers, these determined New Yorkers have made the decision to participate in our democratic system by collecting petition signatures to help get candidates on the ballot.

Many of them, however, did not make this decision of their own volition. Instead, they were given an ultimatum by our governor, our legislature, and our judicial system: have unnecessary, person-to-person interactions during a pandemic, or you/your candidate can’t run for office.

Disappointed does not begin to capture how the three of us and over 350 New York candidates are feeling. We are scared, and deeply concerned. After a year of failing to plan, months of public consternation, and a dismissal by a state judge, candidates, their staffs and volunteers are now forced to put their health, and the health of prospective constituents, at risk all in the name of an archaic, outdated process.

Even amidst the state’s vaccination effort — which does not currently make candidates and their campaign staff and volunteers eligible — New York continues to report nearly 10,000 new cases a day statewide, and there have been more than 47,000 deaths from this disease in our state. Still, even vaccination is not a cure-all; the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention cautions that vaccinated individuals can contribute to the spread of COVID-19.

New York has been in a state of emergency since January of 2020, which means our state elected officials and party leaders had over a year to figure out a safe way to petition and determine which candidates make the ballot. Instead our government failed us with their inaction and people are going to be forced into tens of thousands of unnecessary interpersonal interactions.

Governor Cuomo, who has repeatedly put politics before the health and safety of New Yorkers, has state-of-emergency authority that would allow him to waive the 2021 designating petition signature requirements. No one questioned his executive order last year that immediately suspended petitioning and lowered the thresholds, and yet with ample time to better prepare this year, the bare minimum was done.

The Legislature also failed to adequately step in, and instead let proposals languish for months, only to end up passing legislation that does absolutely nothing to protect petitioners. The bill signed by the Governor lowering the total signature requirements is not enough. Exposure is exposure, and we now have several new, highly-contagious variants of COVID-19. Reducing the amount of time New Yorkers have to petition does not help either, we are now cramming together during that shorter time period to collect signatures. While the state of our economy is a valid concern and may warrant the opening of certain businesses, petitioning has zero economic purpose. We are talking about a some-risk, no-reward endeavor.

Another bill that passed extends County Committee terms for one year, but does not address other volunteer, largely uncontested political party seats, like District Leader or Judicial Delegate. Most importantly, the bill's main flaw is that it essentially creates a county-by-county “opt-in” solution that must be voted on by each county committee.

Other bills were introduced (and even passed) in the Legislature, but either fall far short of truly protecting petitioners, or were left to languish: A bill that prevents anyone from the opportunity to ballot petition is helpful, but extremely limited in who will benefit from it. More so, under this bill, the uncontested candidate would still have to go out and petition.

A bill that would allow for electronic petitioning, which is the strongest proposal in the Legislature, is still sitting in the Senate and Assembly elections committees, even though it was introduced on January 6. Had this bill been passed immediately, the Board of Elections may have stood a chance of implementing an online petitioning infrastructure. We know it’s possible — both New Jersey and Rhode Island recently announced the implementation of online designating petitions to reduce the likelihood of campaigns becoming superspreader events.

Right here in New York, we successfully implemented online solutions for legal processes, including remote witnessing and electronic signing by notaries, and remote Board of Elections hearings due to the dangers posed by COVID-19. But even if this bill allowing for electronic petitioning was passed within days of its introduction, two months notice may not have been enough for a body that is marred by inadequate funding, bureaucracy, and politics.

That’s why, when it became crystal clear our leaders would not go beyond a careless “we’re working on it” approach to prioritizing public health, we filed suit. But even during the hearing, we knew that the dangers of creating a superspreader event were not truly considered.

Some of the “alternatives” proposed by the judge, like setting up plastic tents along the city sidewalk to protect petitioners, are simply outrageous and not feasible. Anyone who’s petitioned knows that it is an intimate, one-on-one interaction. The petitioner must first engage someone, most often a stranger, and ask them to stop and speak, explain why they stopped them (because many people are unaware of this process), convince the person to sign for all the candidates on the petition, and witness the person sign. In large cities where you can’t canvass door-to-door to target voters, the most effective way to do this to collect the appropriate number of signatures is to stand on crowded and busy pedestrian areas.

Our electeds may have reduced the number of required signatures, but let’s look at a quick example, one that City Council Member and comptroller candidate Brad Lander shared: if a New York City Comptroller candidate needs 2,250 signatures under the new law, they’ll most likely collect three times that amount (which is standard practice for all candidates), amounting to 6,660 signatures per candidate. With seven candidates running for comptroller, that’s at least 50,000 mandated interactions. And let’s not forget: this doesn’t include candidates running for Mayor, City Council, Borough President, Manhattan District Attorney, District leader, or Judicial Delegate. Council Member Lander’s example was for only New York City, but we will have candidates throughout the entire state engaging in these dangerous interactions. How can we collect signatures while maintaining social distance?

The truth is we can’t. New Yorkers deserve better, and we hope the state Legislature will reflect on the danger they put hundreds of thousands of people in, while most of them do not have to lift a finger and petition until 2022. To all of our fellow candidates, campaign staffers, and volunteers: please take care of yourselves, your neighbors, and your communities. Double-up on masks, rotate and clean pens, and commit to not challenging each others’ signatures.

Despite the failures of many, let’s get through this safely.

***

Erica Vladimer, Lauren Trapanotto, and Corey Ortega are candidates for office. On Twitter @EricaForNY, @l_traps, & @mrortegany.

***

Have an op-ed idea or submission for Gotham Gazette? Email This email address is being protected from spambots. You need JavaScript enabled to view it.

Expanding Educational Opportunities for Our Youngest Learners

Kids at school (photo: Michael Appleton/Mayoral Photography Office)

Economic and racial inequities have been a plague in New York City’s education system for decades, and the COVID-19 pandemic has only exacerbated the situation for our most vulnerable students. Faced with the reckoning of remote learning, we’ve been bombarded with stories of how our public schools lack the resources to adequately equip students with the technology they need to stay afloat, while something as simple as providing wi-fi to every child has only been met with excuses. Yet often lost in these stories is how the discrepancies in access to quality early education has created this game of “catch up” the city, parents, and students now face.

In Ridgewood, Maspeth, Glendale, Middle Village, Woodhaven and Woodside -- which make up Queens’ 30th City Council District -- we see these stories playing out along geographical and racial lines every day. It’s no coincidence that the success rates on the specialized high school admission test (SHSAT) for students at schools in predominantly whiter areas of our district are 400-500% higher than at those with a higher foreign-born population. And while much attention is paid to test prep or teaching at the middle-school level, not nearly enough attention is paid to how disparities begin for our students as early as day-care.

Financially, the cost of day-care and early child education averages between $10,000-$15,000 per year. This is before you take into account that parents who cannot afford to pay exorbitant costs for day-care and education must sacrifice their own jobs and economic well-being to look after their children before they are old enough to receive a free public education. Moreover, when you consider many of these same parents may not speak English as their primary language, it’s easy to understand how we’re failing our students at their most pivotal age.

This is why it is imperative that our local legislators continue to fund and expand early childhood educational programs and raise awareness of the resources already available to our families.

Studies have shown that an investment in early childhood education is an investment in our society and public safety at large. A comprehensive review of economic analyses of pre-K concluded that for every $1 invested in early childhood programs, there is a $17 return to society, and a dramatic decrease in the incarceration rate.

Throughout the country we’re seeing more states reap the benefits of investing in early childhood education. Programs like Universal Pre-K provide a free, high-quality education for children starting at four years old, and cities like New York City and Washington D.C. have implemented programs that expand universal free education for children as young as three. Expanding these programs allows families to get an early start on their child’s educational needs, while simultaneously alleviating the financial burden of child care for every parent and opening up opportunity to earn additional income.

Additionally, Pre-K and 3-K For All in New York City offer dual language classes and special education for students who are learning English as a second language and for students with special needs, respectively. I am especially proud of these programs as I helped consult the Department of Education during their implementation.

It has not been lost on me that throughout District 30 it’s been the Polish- and Spanish-speaking populations that have been hardest hit by the pandemic. Parents have had to take on the role of educator, provider, and caregiver while being forced to navigate the educational space at a disadvantage. According to the Department of Education’s MySchools directory, there are over 80 universal pre-K school locations in District 30, but none that offer dual-language programs or secondary language support. This despite a demographic that is nearly 40% Hispanic and 50% foreign born. And while there are paid, dual-language 3-K programs that offer discounted rates for families who qualify, there are no public, city-funded 3-K programs in all of District 30.

Yet these problems offer us a way to provide incentives for not just families, but the teachers and educators who we would rely on. By expanding and reforming the bilingual certifications needed to teach younger children, we can offer scholarships and financial aid to student-teachers who can teach languages like Spanish, Chinese, and Polish at an introductory level, helping provide educational support for both our children and their instructors.

From every perspective, investing in early child-care and education is not only the right thing to do, it is the financial and morally prudent thing to do. Given the evidence, the question is not if early childhood intervention will benefit communities in the long run, but how quickly can we utilize our resources to best support the programs that equip families and children for school readiness and success. Our children deserve the opportunity to thrive and investing in early childhood education is how we ensure they can do so.

I will continue fighting to ensure that every family has access to early childhood education, expand educational programs in every neighborhood so no child falls behind, and offer resources tailored to the needs of our students.

***

Juan Ardila is a Democratic candidate in the 30th City Council District, a resident of Maspeth, and the first Latino to ever run for the seat. On Twitter @JuanArdilaNYC.

***

Have an op-ed idea or submission for Gotham Gazette? Email This email address is being protected from spambots. You need JavaScript enabled to view it.