Segregated Schools: Shame of The City

New York City schools, argues Kozol, are in many ways unaffected by the Brown decision of 1954. |

Stuyvesant High School is one of the most vivid symbols of the consequences of decades of systematic racism in the United States. Black and Hispanic children make up about 72 percent of the citywide enrollment in the New York City public schools. At Stuyvesant – the most prestigious public school in the city – they make up less than six percent of enrollment.

In fact, the percentage of black kids who go to Stuyvesant has decreased dramatically in the last quarter century. Twenty-six years ago, black students represented almost 13 percent of the student body at Stuyvesant; today they represent 2.7 percent.

I'm not implying that the administration at Stuyvesant is made up of racists – they must be remarkable people to run such a wonderful school. Black and Latino students do not have access to Stuyvesant because they have not been adequately prepared to compete with the other students applying for a limited number of spots. What the racial gap in admissions represents is the devastating end result of the failure to educate black and Latino children effectively from the age of two and a half up to their 8th grade year.

It is impossible to improve the inferior quality of the education that minority children receive without confronting the fact that they are attending increasingly segregated schools; separate is still unequal. Yet that is exactly what New York policymakers are trying to do. Until it begins to follow the lead of several smaller cities across the country, New York's school system will continue to fail to serve the majority of its students.

THE RESEGREGATION OF AMERICAN SCHOOLS

|

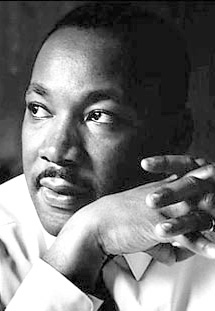

"We’ve got to come to see that the problem of racial injustice is a national problem. No community in this country can boast of clean hands in the area of brotherhood. Now in the North it’s different in that it doesn’t have the legal sanction that it has in the South. But it has its subtle and hidden forms and it exists in three areas: in the area of employment discrimination, in the area of housing discrimination, and in the area of de facto segregation in the public schools. And we must come to see that de facto segregation in the North is just as injurious as the actual segregation in the South. "

Martin Luther King, Speech at the Great March on Detroit in 1963.

Segregation has returned to public education with a vengeance, as a result of years of federal policies that started in the early 1990s when the US Supreme Court and the local federal courts began to rip apart the legacy of the Supreme Court's 1954 school desegration ruling, Brown v. Board of Education. The percentage of black children who now go to integrated schools has dropped to its lowest level since 1968.

New York State is the most segregated state for black and Latino children in America: seven out of eight black and Latino kids here go to segregated schools. The majority of them go to schools where no more than two to four percent of the children are white. Only Illinois, Michigan, and California come close to this abysmal record. The level of segregation statewide is due largely to New York City, which is probably the country's most segregated city

When it comes to residential integration and school integration, New York has an undeserved reputation for progressive values. For the last 40 years it has been one of the most regressive cities in America, in many ways unaffected by the Brown decision. The courts never tried to integrate New York, and the major media, including the New York Times, consistently opposed any drastic measures that would significantly integrate the city's system.

BLOOMBERG AND KLEIN'S EDUCATION REFORMS

The position of chancellor of New York City schools is an almost impossible job. I sometimes think that job was created so that one man or woman in New York could die for our sins every year. Like it or not, Chancellor Joel Klein's real job description is to mediate the separation of the races and put the best possible face on a flagrantly unequal system.

The Bloomberg administration's educational reforms have been centered on mayoral control of the schools. This probably gives the mayor and the chancellor better tools to approach the problems in the schools, and it is to their credit that they have used this power to get rid of the rote and drill, stimulus-response curriculum that was being used in failing schools across the city.

But we have wasted too much time in the last 20 years fiddling around with governance arrangements. The fact is that whether the school systems I visit are governed directly by the mayor independently, or through an appointed school board or an elected one, virtually all cities face the same calamity: a devastating gulf in the quality of education offered to minority kids as opposed to white kids.

NEW YORK CITY AND SMALL SCHOOLS

Alleged panaceas have been introduced repeatedly in every urban district since I first walked into a classroom in 1964. Every five years there's a "solution" to the problems of separate and unequal education -- a solution that never addresses the problems of either separate or unequal.

The newest magic pill that is being advertised is small schools, and it is one that Bloomberg and Klein have bought into.

Small schools are usually less chaotic than big schools; they are sometimes more intimate and relaxed than big schools. But the small school concept, which no one is proposing for the schools in white suburban districts, is essentially an anti-riot strategy for segregated children, an anti-turbulence measure, a short-term solution to perceived chaos in large segregated schools. Small, segregated, and unequal schools are only an incremental improvement over large, segregated and unequal schools. They don't address the basic issues.

In fact, in New York City small schools are being used, intentionally or not, in ways that widen the racial divide. On the one hand, we're seeing small schools that cater to very artistic, upscale Greenwich Village families. These schools are overwhelmingly attractive to white people. On the other hand, we're seeing a proliferation of so-called small academies for black and Latino students with names like Academy of Leadership, or the Academy of Business Enterprise. (In some other cities such schools are explicitly given names like the African American Academy). These schools tend to be even more segregated than larger ones.

At this point New York City, like many cities in America, is rolling out small schools as this year's trendy attempt to do an end run around inequality and segregation. It is not going to work on a significant basis. I predict that within ten years the entire small schools movement will collapse and be declared a failure.

REFORMS THAT ADDRESS THE REAL PROBLEM

Today, Bloomberg and Klein are trying their best to sweeten the pill of segregation rather than confronting it. But they have to confront it, and smaller cities have offered a model of how to do so.

The metropolitan New York City area is one of the most adamantly resistant sections of the nation, in which there has never been any serious attempt at voluntary integration programs between the city and the suburbs. This is in great contrast to St. Louis, Milwaukee, Boston, and several other cities, all of which have successful suburban integration programs for inner city children. While some of these programs were initially begun under court orders, others (Boston's, for example) are entirely voluntary and are supported by the parents of the suburbs because they believe that integrated schooling is of benefit to their own children.

In virtually all of the urban-suburban integration programs, the high school completion rate and graduation rate for black students average 90 to 95 percent or better, and the overwhelming number of these black kids go to college. There are waiting lists for all these programs; in St. Louis there are four applicants for every opening.

It is only about a fifteen minute ride from a typical, segregated Bronx neighborhood to one of the very first suburbs to the north of the Bronx – Bronxville, for example, one of the most affluent communities in the United States. It spends nearly $19,000 per pupil, compared to $11,600 in the Bronx. It has zero percent poverty in its public schools. Only one percent of its students are black or Latino. It would be a very short ride for almost any Bronx child to go to school in Bronxville or any of the other suburbs immediately to the north.

The chancellor and the mayor ought to be advocating for cross-district integration with the 40 or 50 affluent suburban districts that immediately surround New York City. Admittedly, this step would take extraordinary political audacity.

If he wanted to take a really visionary stance, Mayor Bloomberg could also turn small schools from institutions that reinforce segregation into places that help break it down. He could provide incentives for small schools to be created with the explicit goal of bringing the poorest children and the richest children, black, Latino, white and Asian children together in the same classrooms. If he were to take that step, and use the small school concept to achieve that goal, then he would have left behind a really decent legacy. He would have begun to make a serious dent in the intense racial isolation that continues to make New York the shame of the nation.

Jonathan Kozol is the author of seven books on urban education, and the winner of the National Book Award. His most recent book is "The Shame of the Nation: The Restoration of Apartheid Schooling in America."

Â

Arts Education

The principal of St. Nicholas School in the Bronx makes it clear what she thinks of arts education when one of her teachers enters her office unbidden.

“Who’s watching your class?” the principal, Sister Aloysius, asks her teacher, Sister James.

“They’re having Art,” Sister James replies.

“Art,” the senior nun snorts. “Waste of time.”

“It’s only an hour a week,” Sister James replies.

“Much can be accomplished in 60 minutes.”

This exchange is near the beginning of John Patrick Shanley’s hit Broadway play, “Doubt,” and serves in part to establish the principal’s rigid character. But while the principal and the school may be fictional (“a parable,” Shanley calls it), the attitude is for real.

“Many educational leaders in New York City…do not value art as a core academic subject that requires time and the attention of…principals, teachers and parents,” concludes a report on arts education in New York City public schools (in pdf format) released by the City Council in June of 2003.

That report and three hearings of the education committee of the City Council picture arts education as spotty and undervalued, with inequitable resources, inadequate instruction, insufficient facilities, and a shortage of qualified arts educators -- but also find much to feel hopeful about: In the New York City public school system, “you can find absolute state-of-the-art enlightened arts education,” Richard Kessler, executive director of the Center for Arts Education, testified at the third of the council hearings last month. “It’s the best of times and the worst of times.”

From Anti-Art To "The Arts Administration"

The still-widespread attitude that the arts are a “frill” helps explain why funding for them always seems endangered. A New Yorker cartoon in 2003 depicted one caveman complaining to another: “Why is the arts budget always the first thing to be cut, when you know damn well it’s the only thing that separates us from the monkeys?” This was no joke during the 1970s fiscal crisis, when the arts were virtually eliminated from the city’s public schools; all art, music, drama and dance teachers were laid off. Although the city’s cultural institutions and individual artists tried to fill in the gaps, with the aid of newly-created private non-profit organizations like ArtsConnection and the Center for Arts Education, it took more than two decades before City Hall and the school system itself committed to restoring arts funding and the arts curriculum. The New York City Department of Education says it spent roughly $250 million for arts education in the last school year (out of a total budget of some $13 billion.)

It is a sign of progress that Sharon Dunn, who is newly in charge of arts education for the Department of Education, officially acknowledged that an anti-art attitude is part of the problem, though she couched this politely:

“One of the areas identified as most in need of development,” Dunn testified last month, “is the need to acquaint school administrators with the benefits and elements of arts education.”

Dunn’s testimony at the October 31 council hearing was intended to emphasize that the Bloomberg administration, Dunn said, “has made arts education a priority.” She gave as one small example among many the creation of a “cultural pass program for school leaders,” with funding from the Bank of America, that enables school principals and other educators to attend cultural events for free (which would presumably seduce them out of any bias.)

But the “embodiment of a deep commitment” by the mayor, chancellor and school system, she said, is the “Blueprint for Teaching and Learning in the Arts.”

This echoes statements that Mayor Michael Bloomberg made during his re-election campaign. In answer to a questionnaire by an education advocacy group (question 17), he wrote that he was “dedicated to developing and improving access to quality arts education for every public school student in our city.” Evidence of this commitment, he said, was that his administration “created and implemented the city’s first comprehensive kindergarten through twelfth grade art curriculum in visual arts, music, theater and dance.”

The New York Times more or less reiterated this point, in a laudatory article on the front page of the Arts and Leisure section entitled “The Arts Administration” that asserted that the Bloomberg administration "has done more to promote and support the arts than any in a generation" and singled out its “development of a mandated arts curriculum for public school students...the first of its kind since the city gutted arts education during the 1970's fiscal crisis.”

But that article itself has been criticized for its omissions (mostly involving criticism of Bloomberg budget cutbacks to cultural organizations) and for its timing -- just two weeks before the election. And, as the most recent hearing made clear, some critics see a sharp disconnect between what officials say and what actually exists.

Why Arts Education Is Not A Frill

It should be self-evident that learning to play a musical instrument or to appreciate a painting or to know how to respond to performances at Lincoln Center would give students a sense of discernment and delight that would last their entire lives. But merely providing a lifetime of pleasure and fulfillment seems a hard sell at a time when there is so much worry that American youth (all Americans, actually) are ill-prepared for the economic challenges of the future. The result of such concerns has been a emphasis on teaching "the basics" -- and on test scores.

The arts can easily seem an "obscure" consideration, said Richard Kessler, "when you look at the push being made in reading and math...and [at]the ways in which school leaders are evaluated" -- i.e. by test scores.

But if it may be difficult to test and grade individual achievement in the arts, the arts have been shown to offer concrete and measurable scholastic benefits. Research studies (in pdf) indicate that involvement in the arts –- whether in school or after school; as a participant or a spectator -- enhances young people’s ability to learn in other subjects. Sustained participation in music, for example, was shown to be connected to success in mathematics; and participating in theater was correlated with success in reading. One study found that young people exposed to the arts are far more likely to be recognized for academic achievement, to participate in a math or science fair, and to win an award for writing an essay or a poem.

The arts have proven a reliable way of reaching students who, for one reason or another, were alienated from their studies. The arts involve parents and other members of the community in a way that other “schoolwork” usually cannot.

The arts also can develop empathy and instill confidence in young people, and (in the words of the City Council report) “provides them with a language to understand and contribute to the world around them.” This was demonstrated in an especially compelling way in Born Into Brothels, an Academy Award-winning documentary about the children of prostitutes, whose lives were transformed when they were taught how to take photographs.

To Xanthe Jory, executive director of the Bronx Charter School for the Arts, "the arts can be a catalyst for change, not only in individual students, but also in the life of the school."

The City's Blueprint For Teaching And Learning In The Arts

The core of the city’s efforts in arts education is called Project ARTS (standing for Arts Restoration Throughout the Schools), and the core of Project ARTS are the recently-completed blueprints for the arts -– there is one blueprint each for theater, for visual arts, for music and for dance.

In each of the four artistic fields, and in every grade, the blueprints offer five “strands” of learning that begin with the making of art, but go beyond it. A well-rounded arts education would mean growing mastery in all five approaches. To use the terminology that the blueprints use, the five elements include (with examples randomly selected from the blueprints to illustrate):

1. “Making Art”

In theater, for example, students are expected to achieve certain “benchmarks” in each grade, in acting, directing, designing, technical work and playwriting. Second-grade actors, for example, should be able to “make appropriate use of costumes and props in activities, sharings and performances” while fifth-grade actors should “demonstrate the ability to memorize spoken word and staging within a performed work” and eighth-grade actors would be able to “apply a knowledge of the characteristics of various genres in performance, including tragedy, comedy, farce, improvisation and musical theater.”

2. “Literacy in the Arts”

In the visual arts, a 12th grader would be asked to “identify issues raised by a controversial work of art,” and expected to know enough about art history and the vocabulary used in interpreting a painting to write both a review of a museum exhibition, and “wall text, labels, catalogues and promotional materials for a student-curated exhibition.”

3. “Making Connections”

A fifth-grade music student learning how to play “This Land Is Your Land” could be assigned to research the period in which Woody Guthrie composed the song, what issues engaged him, and how his song compares to Irving Berlin’s “God Bless America.” The student, while improvising harmonies for “Ode To Joy,” could be assigned to explore other examples of harmony – in poetry, in painting, in architecture. The connections being made are to other fields and to society in general.

4. “Working With Community And Cultural Resources”

A dancer in the eighth grade would be asked to attend professional dance performances and report on them for her schoolmates, or use the New York Public Library for the Performing Arts to research American social dances.

5. “Exploring Careers And Lifelong Learning”

The point here, said Sharon Dunn, is to drive home to the student that “as you learn to look at art and find that you have a passion for it, there's actually a place at the end of this path [where] you can earn a living.”

But Dunn stresses that an arts education is for every student, not just those who might one day become professionals, and the blueprints should also function as resources for teachers in every discipline.

Falling Short

At the recent City Council hearing, Eva Moskowitz, the chair of the council’s education committee, seemed unimpressed with the blueprints. "I'm all for being ambitious," she said at one point, "but given...the fact that there's chaos in many of our schools, it just seems like I'll have great grandchildren before we'll have this implemented...I mean we barely have schools that have bands."

Moskowitz and other members of the council were especially taken aback when Dunn said she did not know what percentage of the public schools currently offer their students an excellent arts education -- nor, when pushed, would she offer an estimate or even hazard a guess.

"I find it profoundly troubling," Moskowitz said, "that either they don’t want to say that only five percent of their schools are meeting the standard...or they honestly don’t know."

While Bloomberg talks of having “created and implemented” a “comprehensive” curriculum, in other words, there’s proof only of the blueprint having been created, not implemented, and, to Moskowitz and others, the blueprint is not even really a curriculum (much less a comprehensive one) but a sometimes vaguely-worded and often obvious set of goals and guidelines.

At the hearing, and in its report, the education committee enumerated other concrete challenges, among them a lack of such facilities as art or dance studios, an inadequate supply of basic material and equipment such as musical instruments, and a shortage of arts teachers. Some 150 public schools –- more than one in ten -- still have no full-time arts teachers of any kind. (Currently, there are reportedly 2,343 licensed art teachers across the city, including only 136 teaching theater and 124 teaching dance.) While the school system is hoping to hire more, they are having trouble finding them, in part because schools of education (taking their cue from New York City’s long-time lack of interest) eliminated their programs to train arts teachers. To make things worse, Richard Kessler observed, “we are hearing regularly from schools where arts specialists are being let go.”

If there is one Web site that offers the most compelling information about the state of arts education in New York City public schools, it is probably not the Department of Education’s pages on the blueprint for teaching and learning in the arts, but DonorsChoose , a site that tries to match classroom needs with individual philanthropists. Here an elementary school teacher in the Bronx asks for help in taking her students on a trip to visit the Guggenheim Museum, and one in Brooklyn asks for help in funding a similar trip to the Brooklyn Museum. A middle school teacher in Queens asks for a few hundred dollars to build a theater library: “Our kids are talented, creative, and energetic. Most of them have never seen a play, much less been a part of one.” A high school teacher in Brooklyn asks for money for three-dollar magic markers. “Our markers have run dry. The students are eager to finish their intricate design work but there is no money for new markers… This is just one more frustration and disappointment in ... lives that are full of substandard supplies and facilities.”

Â

School Choice, School Confusion

Upper West Side parents seeking to enroll their children in elementary or middle school have long run a gauntlet of confusing application procedures, and this year is no different. Parents who want their child to attend the zoned, neighborhood elementary school have it easy. No special application is necessary: All they have to do is register in the spring. But if a child is entering middle school, or hopes to take advantage of "school choice" or "gifted and talented" programs, the student must apply.

In Region 10, which covers the West Side from 59th Street to the northern tip of Manhattan -- and includes districts 3, 5 and 6, the exact situation varies from district to district ñ and from elementary school to middle school. But for many parents and children the next several weeks will feature school visits and important decisions.

Parents may now tour elementary and middle schools. (For a list of elementary school tours, click here; for middle schools, click here.) Applications in Region 10 are due December 16 or January 13, depending on the program.

The schools will inform parents of their decisions between February 27 and March 2, although children not admitted on the first round might be admitted later in the spring.

The notifications dates have been moved up to coincide with those of other selective public schools, such as Hunter College Elementary School, and of private schools, said Robin Aronow, a consultant who advises parents on school choice.

Elementary Schools

Many elementary schools in District 3, which stretches from 59th Street to 122nd Street, have room for children from outside their attendance zone. (A number of schools also have "dual language" programs with classes taught in both English and Spanish.) Principals used to have the authority to admit children and could accept applications from out of district as well as out of zone. Now, children who live in District 3 are given preference for kindergarten spots, and the regional office will conduct a lottery in February to determine who is admitted. Siblings of children currently enrolled will have preference.

The most popular schools admitting children under the lottery program are PS 87 and PS 75. Manhattan School for Children has its own admissions policy.

Children in Districts 5 and 6 may apply to District 3 general education programs, but District 3 children get preference, and regional officials predict there will be few seats available for out of district children. Applications are due January 13.

Children in District 5 in central Harlem don't have elementary school choice. (They may, however, apply to gifted programs.)

Children in District 6, covering Washington Heights and Inwood, have a number of school choice options, including Hamilton Heights Academy, Washington Heights Academy, The 21st Century Academy (PS 210), Amistad and Muscota. There is no entrance exam for these schools.

Gifted and Talented Programs

Two Region 10 schools -- the Anderson School and the Special Music School -- accept gifted children from all five boroughs. In addition, the Department of Education has set up "gifted and talented" programs at a number of elementary schools in the region. To be admitted, children must take an IQ test and their nursery school teacher must complete a Gifted Rating Scale assessment. For the most part, schools only accept students from within their district, although District 5 parents may apply to the dual language gifted and talented programs at two District 3 schools -- PS 165 and PS 163. Parents must rank programs in order of preference.

While children living in a school's attendance zone or siblings of students already in the program do not get any preference for the gifted programs, siblings are guaranteed a seat in the general education program in the same building. "The intent is not to break up families," said District 3 superintendent Judi Aronson.

Applications for gifted programs must be submitted by December 16, although test results may be submitted later. The region will test children between January 3 and February 10.

Middle Schools

Tours for middle school are in full swing now. Fifth graders have already received their applications and must submit them by December 16, although some guidance counselors want them sooner.

Inside Schools features profiles of individual middle schools.

A directory of District 3 middle schools is available at the office at 154 West 93rd Street, or by contact Walter Friedman at 212 678-2885.

In addition to the district choice program, District 5 students have a number of options to which they can apply directly, such as Kappa II, Kappa IV, and Frederick Douglass Academy. The district will hold a middle school fair on December 10, from 9 a.m. to noon, at Roberto Clemente Middle School, 625 West 133rd Street.

Students in District 6 will have some new middle school options of their own, including a school operating in conjunction with City College, but itĂs too soon to know what the new and expanded programs there will be like. For more information, contact parent support officer, DJ Sheppard at 212-678-2880, Ext. 1.

AFTER SCHOOL PROGRAMS

Working parents have long struggled to find quality care for their children after school and during school vacations. Now, the city has published an online directory of 500 free after-school and vacation programs. Just type in your ZIP code and find the program nearest you.

The directory is part of a new initiative that consolidates most free, city-funded after-school activities under one umbrella. Community organizations will run programs during school holidays and vacations ñ even those irritating half-days will be covered. The directory also includes some programs for teen-agers and some summer programs, such as arts classes, operated in the city parks.

The directory doesn't include all the after-school programs in the city, just those receiving funding from the Department of Youth and Community Development and the Department of Education.

Individuals schools may know about other programs, including private programs that charge a fee, or programs run by a school PTA. For additional options, especially for older children, parents should also consult the directory of Beacon schools on the youth department Web site. Beacons are the 80 schools that are open after school and evenings as well as during vacations. The free programs run by community organizations include community services as well as sports, homework help, and literacy classes.

Although the consolidation of the after school programs and the publishing of a new directory is mostly good news, there are some concerns. While the city has opened new after school programs in neighborhoods that sorely need them, such as Far Rockaway, it has taken funding away from those in neighborhoods where the need is not considered as pressing, particularly in Manhattan. That means that some programs that have to find other funding or close.

"The goal was a noble one," said Michelle Yanche, director of the Neighborhood Family Services Coalition, a policy and advocacy organization. "The problem is that they tried to address is without additional funding. The result is that you are shifting resources from young people who truly need it in one community to young people who truly need it in another community."

This topic page has been adapted from articles that originally appeared on Insideschools.org, an independent guide to New York City public schools sponsored by Advocates for Children.

Â