State Lawmakers Weigh Options For Hurricane Sandy Relief

ALBANY, N.Y. — A house disemboweled by flooding, a boat in the middle of a normally busy road, boilers and basements under water, a boardwalk blocks from where it normally stood.

While normal life has returned to some sections of the city, these images are still seared into the minds of residents of parts of Queens, Staten Island, and Brooklyn, and for others the destruction wrought by Superstorm Sandy is still physically inescapable, forcing them to live without power, heat, a regular place to sleep or in homes infested with mold.

“If you don’t live in these impacted communities you just wouldn’t know what it is like,” said Republican state Sen. Marty Golden, who represents parts of south Brooklyn that were hard-hit by the storm. “People living just two miles away from some of this have no idea what the conditions are. Sandy has not left us and she is going to be around for a long time.”

Golden is a member of the State Senate's Bipartisan Task Force on Hurricane Sandy Recovery, which could release details on a package of legislation Monday aimed at helping residents still reeling from the storm. Legislators are keen to start delivering money to rebuilding efforts so they can show their districts that they can bring home badly needed relief funds, especially with state budget negotiations moving faster this year and President Barack Obama recently signing $60 billion relief bill.

In exploring their options, legislators say have they focused on marshaling services, resources, specialized labor and insurance experts to boost rebuilding efforts and to get people back to normal faster. Proposals would eliminate sales tax on cars and home building materials for Sandy victims.

There are also a number of programs designed to help Sandy victims that legislators want to see extended. They include an informal program announced by Cuomo where New York-chartered banks and other participating institutions can give homeowners in areas impacted by Sandy a break on their mortgage payments. Another instituted by the Internal Revenue Service allows Sandy victims to borrow from their 401k without penalty to, as Golden says, “allow them to get whole again.”

The task force toured communities in Brooklyn and Staten Island on Thursday in an effort to get a sense of the scope of Sandy’s lingering devastation, which is not obvious when just looking at the numbers — but the numbers are still staggering; 305,000 homes damaged or destroyed, displacing over 40,000 in the NYC area alone, and impacting over 265,000 businesses. “We need a plan,” said Golden. After the tour, the members of the task force held a roundtable discussion with labor and community leaders, politicians and first responders.

“We intend on putting together a comprehensive package of legislation,” said Sen. Jeff Klein, head of the Senate’s Independent Democratic Conference and a member of the task force, at Thursday's hearing.

The task force formed in the wake of the announcement that the IDC would be joining forces with the Senate Republicans to keep Senate Democrats from taking control of the chamber despite what at the time looked like a numerical victory.

At Thursday’s meeting of the senate task force, Sen. Diane Savino described just how damaging Sandy has been for businesses to her district on Staten Island. “One of the things that gets lost,” Savino said, “is the impact the storm also had on the north shore. Most people don’t realize what the impact of our industrial waterfront has been tremendous. We’ve got businesses that have been put off-line — who can forget the picture of that giant tanker washed out on to Front Street? So, the damage has not just been to residential districts, it’s also been to our business districts."

Golden said that he is particularly concerned with those who have been mentally and financially traumatized by Sandy and don’t know where to go for help. “Who knows how many people have had mental breakdowns," he said. "Who knows how many people are in the stages of bankruptcy. We need to give them the appropriate help to keep them afloat but they need to know to reach out to us."

Democratic Sen. Joe Addabbo, whose Queens district was one of the hardest hit by Sandy, has a list of concerns of his own — some of which are unique to Queens and others that are all too common across the areas impacted by the storm.

“I still have over 7,000 homeowners in the Rockaways without power,” Addabbo said. “There are those homes in Breezy Point that haven't been rebuilt, homes across the district that need rebuilding. There are some businesses that will never come back but there are some mom-and-pop stores that gotta come back for the fabric of the community, and we gotta help them. The money from the bill that the [US] Senate just passed can't come quick enough. It has been three months."

Addabbo has cosponsored a bill put forward by Sen. Daniel Squadron that would give property tax relief to Sandy victims. Addabbo is working on legislation that would give small businesses a small amount of cash to restore their storefronts.

Perhaps the most common concern among legislators is that residents will simply pack up and leave — they suspect that a number of them already have. Golden noted that it is hard to tell just who has abandoned their properties since the storm. “I don’t think we know quite yet how many people have just walked away,” he said.

They say they also must find a way to make sure that rebuilding is not cost prohibitive.

"You know, we have residents who went through Hurricane Irene two years ago and they were just paying off their loans from that and then Sandy hit,” Addabbo said. “Now they are being told they have to raise their house ten feet, or pay thousands in flood insurance. We don't want everyone to pack up and leave. We don't want a flight out of southern Queens."

While state lawmakers consider their options for helping them to rebuild, New Yorkers face a barrage of information about where and how they should — and if they should at all. Last week, the federal government released a draft version of new flood maps for the city that show thousands of homes in harm's way. These homeowners could now be faced with prohibitive flood insurance rates.

Mayor Michael Bloomberg issued an executive order Thursday waiving standard zoning rules to allow homeowners rebuilding in those flood zones to build their homes higher and out of range of floodwaters.

The mayor also adopted a new rule to require a minimum flood-proofing elevation — a move designed to make houses safer and to also possibly lower federal flood insurance premiums. Cuomo, for his part, integrated a plan to buy out residents of shores and flood zones into his budget, saying, “Maybe mother nature doesn’t want you here.”

Both Golden and Addabbo say they have heard from some residents who are interested in the program, but they are also worried about helping those who want to stay.

“I gotta think most residents are saying, 'I chose to live by the water. I want to live by the water.' So we have to help these people meet the requirements that the flood maps dictate and help them financially to make sure they are in compliance," said Addabbo of Cuomo’s proposal to buy out residents.

___

Image of Sandy destruction at Howard Beach, by Pam Andrade, used under Creative Commons license.

A Shrinking Footprint: Geophysicist Klaus Jacob On Rising Sea Levels, Sustainability And Indian Point

NEW YORK — In this post-Superstorm Sandy era, geophysicist Klaus Jacob is regarded by many as something of a seer.

But in his view, the public debate over climate change and what it means for the city has wrongly been focused on extreme weather, and not on the rise of sea levels that will reshape the footprint of the metropolis.

In the second part of Gotham Gazette's sit-down interview with Jacob, the climate change expert speaks about the city's energy policy, long-term planning for sustainability and why he thinks Indian Point nuclear power plant needs to be shut down.

Jacob was interviewed at at his office at the Columbia University Lamont-Doherty Earth Observatory in Palisades, N.Y., in late December.

Need to get caught up? Read the first part of Gotham Gazette's interview with Jacob here.

GG: So you’re saying that New York City’s density patterns will have to change because of our shrinking footprint due to sea level rise?

KJ: The housing density patterns of the city will have to be totally changed. When you look at the patterns of our population changes from the 2000 to 2010 census (he refers to a map on his computer screen) there are blue areas where there was a population increase. And red areas, where there was population decrease. Where are the blue areas? On the waterfront, mostly on the west side. Areas like Chelsea … Really got built up on the waterfront … All in the A zones, and A overlapping on B.

Where are the red zones? Washington Heights. Midtown. There’s one little anomaly, which is around the WTC. That is red and we know why. But that’s a temporary blip. In the next decade it will probably become quite blue — from 2010 to 2020 — because it will be re-occupied, both business-wise but even residential … It (density) goes up in the wrong places, and it goes down in the wrong places.

Brooklyn Heights will become prime real estate. Morningside Heights, Washington Heights ... Our graveyards up in Queens, Brooklyn, Prospect Park, Central Park will be prime real estate. Not that I am saying we should do away with those. But the surrounding areas will be prime real estate.

GG: If you had to make any type of projection — what do you think the city’s next move will be regarding planning for climate change?

KJ: There’s some pretty smart people in the Department of City Planning. There’s been some unfortunate personnel changes in the Office of Long Term Planning over the last year from which they had to recover. They’re all working for the mayor. They can advise him, but they don’t make the decisions, they can only make recommendations. But it is easy sometimes to forget the long-term vision in the day-to-day pressures of decision-making, but ultimately they are well intended.

I sit on a DCP technical advisory board, and I always stress long-term vision … I’m going very strong on that ... I have no power, except the power of the mind. The other people have the real power.

DCP has a HUD (sponsored) project that began way before Sandy, in which DCP assesses how to plan for the waterfront of NYC. How to make a plan, NOT for tomorrow — but rather for some time into the future. That’s in the works … Sandy … provided (data for the study) that actually wasn’t available before. Once that (plan) gets accepted by the mayor, it should influence the Department of City Planning, the Department of Environmental Protection, the Department of Buildings …

GG: How does the city’s energy policy relate to planning for climate change?

KJ: Upfront, I should say I’m not an energy expert. I have limited knowledge and some opinions but they are not expertly based. They are more common sense-based. I’m also on the board of Scenic Hudson, where we occasionally discuss relevant energy policy.

In general, the greening of the city is making relatively modest positive progress. But I would call it modest. It’s not as aggressive as one could be. (Utilities) still behave in a very traditional way. They certainly are not up to sea level rise and climate change. They still look at their traditional distribution system. We are far away from a smart grid for NYC.

That is not to say that there aren’t many buildings that come online in NYC that are LEED certified. But that’s pretty much within the realm of what the owner wants to pay for and do. The city encourages it, but the building code doesn’t necessarily have the teeth that it would need to push all these measures through in a much more accelerated way.

Again, this is slightly outside my expertise. This needs to be verified and checked.

I think the city could be more aggressive on the energy side. The governor has a plan to shut down Indian Point, which personally I think is a good idea. There are plans to create new power transmission to NYC by laying a DC line in the Hudson, through Lake Champlain, all the way up to Quebec … to get cheap waterfall hydro-electric power into NYC with a DC-to -AC converter station, probably in Yonkers. From then on, it would be traditional power distribution into the Con-Ed grid.

That new source would replace a good chunk of Indian Point in terms of its normal production. There is still a need for peak time additional resources if we don’t change our use pattern. You still see all of the skyscrapers lit up in the night. Do you want to see black skyscrapers, or visible skyscrapers? It’s not very green to have all those visible skyscrapers in the night. Would it change the character of the city? Yeah, it would. But what is more important? This is something that hasn’t been discussed much. Is Times Square the right thing to do?

There’s all sorts of stuff that could be changed to make it a greener city, but it would be a darker city. So the question is, how can we make the city greener and have a little bit of light for our joy and amusement and for businesses.

We have changed water use in NYC heavily by metering individual households in buildings that before had just one meter for all. Water usage over the last ten years has gone down incredibly, which saves NYC on the infrastructure side since it doesn’t have to provide new capacity for the next million people … (by bringing) new water supply into the city.

We could do the same thing on the electric side. In many cases, consumption of a large building is just divided by the number of households … It’s buried in the rent, not on an electric bill. If we could find means and ways to charge people for what they’re really using, including inside skyscrapers … And maybe put a city tax on electricity. And then use this tax to do smart urban planning and relocation of populations. A cap and trade policy on a city basis. Which of course you can’t do, because everything has to be approved up in Albany. And we know where congestion pricing went.

GG: When Gotham Gazette interviewed Deputy Mayor Cas Holloway, he told us that natural gas would be part of the city’s energy strategy for the indefinite future.

KJ: It’s true that natural gas is a better fuel than coal, or diesel or fuel oil that we burn in our furnaces and boilers … In the first two to three minutes there’s this incredible black smog coming out. That wouldn’t happen with natural gas. It’s more efficient and whether we like it or not for the time being, an abundant resource. I don’t trust the governor that he will clamp down forever on the fracking situation.

Holloway is probably unfortunately right on that. I say unfortunately because it feeds our fossil fuel addiction. We have to get away from that kind of energy addiction. If we would spend as much money on a smart grid with photovoltaic cells and other energy resources, (or) getting full usage out of the methane from our dumps, as on allowing for conversion of heating oil to natural gas ...

GG: How is the city policy on waste?

KJ: Our waste policy in this city is totally off the mark. Every waste. One-third of the waste in NYC is construction-related. That should not be exported. That should be handled like the Japanese do it. It’s a resource. They grind it up, steel, concrete and all, and form it into bricks and make new ground. We need new ground here. The only areas that stick out … above future flood zones (are) … a dump that’s not far from Kennedy Airport … and Fresh Kills on Staten Island. That will be extraordinarily valuable high land … It’s an engineering and planning issue. We should not export our construction waste to PA. We badly need it inside the city ¬—to make landfills, high grounds, for the future.

GG: Back to what you said before, why aren’t we investing as much in smart grids or harnessing methane from our dumps — as we are in converting to natural gas?

KJ: That’s a rhetorical question. The city doesn’t really control its energy policy. It’s done by the utilities. The city can only change the building code. And to the extent that buildings have a difference in their energy usage, it (the city) can influence the energy policy. It can try to influence the MTA, even though that’s not a city agency, whether they have hybrid buses or not. That influences the energy footprint of the city. There are many things that the city is not in control of.

GG: But the city is facilitating construction of the Rockaway pipeline; they are moving bureaucratic hurdles.

KJ: Yes. Where the city can have influence, it moves it. But it’s limited, and it has to happen not just on the city level, it has to happen on the state level. The Public Service Commission has a lot to do with it. Even if Con-Edison or LILCO wants to do something, they have to go to that commission upstate and say, “can we turn that into an add-on on the utility bill that we charge our customers?” Unless they get that approval, it won’t happen.

There’s so many institutional hurdles. The mayor has the power of the pulpit. He can talk to the governor, to the federal energy commission. That’s where the influence is. The city can make its own buildings efficient, and make public housing efficient. But these are the few things that the city really has direct control over.

It’s such a multi-layer, jurisdictional issue. A lot has to do with institutions. The city could do much better on city planning. All of these developments that are still in the pipeline —Willets Point, Hunters Point. There are these blunt instruments out there — the SEQR (State Environmental Quality Review), the Environmental Impact Statements, where developers are asked to consider certain guidelines. That’s not a good policy instrument because … You have to oblige only existing regulations based on past experience, not regulations that deal with future conditions. There’s no requirement that you have to take sea-level rise into account.

The city finally insisted that a few feet (be added) in certain areas to the old FEMA regulations … Timid attempts to deal with all of these issues. And, on the energy sector, there’s a limited impact that the city can have on the energy realities.

The state can influence how cheap natural gas will be in terms of this fracking business, which I have professional problems with on the earthquake side. The waste water, when re-injected into deep, geological formations — that will come from gas production wells made feasible by fracking — can trigger damaging earthquakes. But in addition, I am fundamentally against it because it fuels our fossil fuel based energy addiction, rather than pushes us toward energy conservation, efficiency, a smart grid, and alternative energy.

GG: But given what’s happening with climate change, why is the city not willing to be more aggressive in moving away from fossil fuels?

KJ: There are individuals in the various city agencies that are champions, but then there’s the rest. Ourselves, together with engineers are very traditional folks ... As long as it’s not in the building code, the ASCE regulations, the International Building Code, nobody has an obligation. It’s left essentially to the owner and to the pulpit of the mayor to convince people to go beyond the codes. Codes are minimum values — they are never reasonable values — intended to provide just minimum safety. Not desirable safety, not desirable energy efficiency.

GG: This seems to tie back to what you were saying before — that the fundamental practice of the city is 10 to 20 years behind the science.

KJ: I’ve been working for 10 years on the seismic building code for NYC. It was a wonderful eye-opener. I understand now why that process takes so long. Everybody wants to have their opinion in there, including the real estate board. We initially thought that we could get something through about retrofitting (existing) structures for the seismic building code, but it was very clear that the real estate board would not go for it … There is a one trillion dollar building inventory and a trillion dollar infrastructure … A lot of assets that you have to deal with.

GG: When will the NYC Panel on Climate Change meet again?

KJ: The Mayor’s Office of Long-Term Planning is in charge and has set a new schedule for it.

GG: Presumably that office will exist after Mayor Bloomberg’s term ends?

KJ: Yes… and the City Council embedded its task into permanence, but it is still driven by individuals on a day to day basis, what’s a priority, what is not a priority…

Any personnel change can set back an agency. It happened with the MTA- they have gone through three CEO’s... Jay Walter left one month after Hurricane Irene … Joe Lhota (who has since left office to run for mayor) had to learn everything from scratch … His staff probably briefed him damn well on what to do for Sandy … He whipped that agency into shape. Luckily there was a lot of pre-Sandy planning, including my own study.

But leadership changes can set an agency like the MTA back politically. The findings (from Jacob’s study on potential MTA climate change adaptation measures) that were delivered internally to the MTA, and publicly to everybody — to the best of my knowledge — never went before the board of trustees. Therefore it never went up to Albany, neither to the Legislature nor to the Governor. If the MTA doesn’t ask for money up there for climate proofing, they can’t take it out of their existing budget to retrofit. There is always more pressure from the public to buy new subway cars, beautify subway stations …

The (recently rebuilt) Battery Park (South Ferry) subway station is totally useless in terms of climate change. Total mis-investment, and many of us told them so, that this is ridiculous. Same thing with the 2nd Avenue subway. It’s fine as long as we are in midtown but … The new downtown Nassau Street station will be in the flood zone. That phase (3) has not yet been financed but the plans are ridiculous. Two stations — new, planned stations — that will be in existing flood zones, so far without protection planned in.

That came up in the MTA blue ribbon commission in which I was raising hell as an observer. I said, “you’re not dealing with the elephant in the room … sea level rise and climate change and all your plans ... But what about the tens of billions of dollars that you have to spend in fixing up your subway system?”… I made a presentation (at the next meeting) and there was silence in the room. It was someone on that blue ribbon commission who agreed, “I opt for a chapter on adaptation to be included in the commission’s report.” Before that, it was all about mitigation in the climate sense; greening, water use, energy, reducing heat island effects … But not adaptation to sea level rise.

I was asked to write the chapter on climate change adaptation. It’s on the books of the MTA, all these recommendations. But the MTA fell terribly behind in the first year and they have never kept up with the recommendations, at least in part, because the board was never confronted with it.

GG: The media presents the MTA’s performance during and after Sandy as something akin to a miracle.

KJ: And rightfully so, in terms of response to the storm. But few covered the real consequence and fallout from all the state-sponsored research — we haven’t changed our risk profile. Our vulnerability is exactly the same as it was five years ago — or even three months ago. Irene should have been the wake up call, and it wasn’t at the MTA, perhaps because of the change in the CEO.

Sept. 11 threw the whole nation back on natural disaster preparedness by about 10 years. You couldn’t talk to FEMA, the Department of Homeland Security about earthquakes, climate change, floods. It was all about terrorism … Who could care about a Sandy coming? That’s the reality. Bin Laden did considerable damage to this country — institutional damage.

GG: Can you talk more about your research on Indian Point?

KJ: We had an earthquake in Virginia in August, 2011 and assessed recordings from a nuclear power plant in the vicinity of that earthquake; they need to be applied as a shaking level to Indian Point to see what could happen. In the mid 1990s we did a study of the Tappan Zee Bridge and provided synthetic ground motions for magnitude 5, 6, 7 earthquakes at various distances from the bridge; they also need to be applied to Indian Point in terms of the dynamic analysis of the structure. I am also concerned about stored fuel on the site which is not protected by any concrete eggshell structure.

The last point is that the guidelines of the Nuclear Regulatory Commission are that a reactor meltdown should have an annual probability of lower than 10 to the minus 6 per year —one in one million chance in a given year. For this you should at least take into account any natural hazard, with an annual probability of 10 to the minus four, or an event with a chance of one in 10,000 in any given year.

If you were to take such a hazard, say a storm surge, a 10,000-year storm surge, in the Hudson River that comes up from the Harbor, then I believe you could potentially be in trouble … I want to see that calculation done. I believe (although I don’t know this for sure) the Indian Point control room is at 15 feet elevation. The Sandy surge was 10, 11, 12 feet. Three or more feet for a 10,000-year surge could get you into trouble.

I don’t know that for sure but I want to see the study done for the 10 to the minus four storm surge passing by Indian Point, and see whether you have control over your standby power that controls the cooling of the nuclear reactors so you don’t get a Fukushima scenario.

GG: Do you believe that Indian Point should be closed?

KJ: Yes. I was not for closing it — suddenly — in the past, but I always said, “no extension of the current licenses.” By the end of 2013, for Reactor #2; 2015 for Reactor #3, that’s it … This 10,000-year storm surge is of concern to me … We are essentially operating a plant where we have requirements on the books in terms of safety that were never fully researched or enforced.

GG: Finally, is there anything that you want to say — relative to climate change — that we haven’t discussed?

KJ: We must not do anything that would produce avoidable risk to future generations. That’s the guiding principle. It’s environmental justice in a way, inter-generational environmental justice. Just like we have environmental in-justice right now. We are creating a problem for future generations, as we have done with greenhouse gases … We shouldn’t add to that burden.

Now you can translate that it into all sorts of details, like developments on the waterfront. We will live to regret this. They (future generations) will have to pay to remove this misplaced junk in the water, and move to higher ground, when we could have done that right now.

____

Image of Hurricane Sandy at night courtesy of NASA.

Storm Surge: An Interview With Climate Change Expert Klaus Jacob On NYC's Post-Sandy Future

NEW YORK — Geophysicist Klaus Jacob has been warning about how vulnerable New York City is to violent weather for years and, more importantly in his view, how climate change and rising sea levels will transform the shape and character of the metropolis.

Weeks before Superstorm Sandy shocked the city and upended the public discussion about preparing for future extreme weather, The New York Times published an interview with Jacob in which he said that the storm surge from Hurricane Irene came only a foot from paralyzing transportation in and out of Manhattan.

“We’ve been extremely lucky,” Jacob told the Times. “I’m disappointed that the political process hasn’t recognized that we’re playing Russian roulette.”

Now, in a sit-down interview with the Gotham Gazette, Jacob describes his struggles to get Washington and Albany, as well as the city, to pay attention to the peril of rising sea levels; how some proposed solutions like flood gates would likely cause more trouble than they are worth; and how he thinks the city's shrinking footprint will lead to more densely populated neighborhoods on higher ground and the loss of coastline.

Jacob became interested in New York City issues in the late 1980s when he successfully prodded local leaders to adopt a seismic building code. Since the late 1990s, he has worked largely on climate change, focusing his attention on how the rise in the sea level and storm surges will affect New York and other global cities. Mayor Michael Bloomberg appointed him to the New York City Panel on Climate Change, which was convened in 2008. Jacob has served in an advisory capacity to city and state agencies on issues related to climate change.

Jacob’s own home, next to a tidal stream and marsh close to the Hudson River, was flooded during Superstorm Sandy’s historic storm surge.

He was interviewed at his office at the Columbia University Lamont-Doherty Earth Observatory in Palisades, N.Y., in late December.

This is part one of a two-part interview. The second part will be published next week.

GG: What are some of the lessons that you think can be derived from Sandy? What are you focused on as you’re moving ahead in your work?

KJ: There is clearly already visible action that [the Federal Emergency Management Administration] has taken. FEMA is in the process of putting out so-called Advisory Base Flood Elevation maps … the 1 percent per year probability flood insurance rate maps. That is a much needed revision — since the last time those maps came out — that every new or modified building will have to conform to … raise it to higher elevations or other measures.

Now after Sandy it became clear that the old FEMA maps were outdated … In many publications, we have said that this is one of the most fundamental things that has to change. ... It was long overdue.

A little side story to that, four to five years ago I was chairing a session in a meeting of the National Institute of Building Sciences in Washington, D.C., on reducing risks from natural hazards. I spotted the FEMA guy in the room responsible for national flood insurance rate maps. I said, “Would the gentleman from FEMA please tell us when they are including sea level rise in their coastal flood mapping program?” He said, “As soon as Congress mandates it.” Which means never, given our Congressional situation where some still argue about the existence of climate change. Sandy did what Congress didn’t do.

It shows the kind of difficulties when we rely on national initiatives. As long as we can do homegrown initiatives, meaning New York City, New York State, or counties, I think we are much better off in getting things done. States can negotiate with FEMA for local solutions, so Congress doesn’t have to mandate it nationwide.

GG: Do the new flood maps use data based on projected sea level rise from climate change? How did Sandy trump Congress?

KJ: There is nothing stated about sea level rise on those new maps. It’s simply an emergency update based on Sandy data. They don’t have to say anything about sea level rise. Now we have confirmation — here is the new data. Officially, climate change doesn’t enter in. That’s how politics works in this country.

GG: Where is the connection between international negotiations on climate change and local planning here? How does the link ever get made?

KJ: That link is 20 years away. We better act on our own behalf. I am acting on my own behalf in my own house (by raising it). It doesn’t come top down—it goes the other way. The pressure will come from the communities. You see this already in certain areas of Staten Island; I have heard that some have voiced great interest in being bought out by FEMA. That’s the kind of grassroots experience that translates into politics. The new FEMA maps will affect from now on what happens in this area. I’m sure there are some people that won’t like it. It costs money to live up to future FEMA regulations.

GG: Are people aware of the costs that are coming? How is the city of New York approaching this question?

KJ: We haven’t seen the new elevations for NYC. The city is holding back on their wording until that info is either informally available to them or released publicly. It’s a touch-and-go situation, everyone is in limbo, and is scratching their heads as to what to do while all of this rebuilding action is going on. A small thing: I raised my outlets to a higher level in my house. I have my furnace in the attic. These are simple measures that you can do. The city really should insist on doing that everywhere too …

GG: These maps will require that people have to elevate?

KJ: Not necessarily for existing structures … If it’s just normal repairs. They are grandfathered in. Right now, with Sandy repairs, it’s not clear where it falls. I believe it’s at the discretion of the city what they want to insist on.

GG: But some areas will no longer be insurable? That may push some of this?

KJ: That’s exactly the concern. I don’t have flood insurance. I am just as much affected as the Battery is. So is the entire Hudson Valley, all the way to Troy, to the Federal Dam just upstream from Albany. Because it’s all tidal.

GG: You’re still sitting on the New York City Panel on Climate Change?

KJ: We haven’t met since Sandy, but NPCC is an ongoing effort that will survive the mayoral change. It has been adopted into city law. The NPCC is an ongoing institution that will periodically advise the city on climate change issues … There is another body — the Climate Change Task Force — both have been written into the city charter. It’s at the behest of the city when it will call for input, and that has not yet happened since Sandy. Also the International Panel on Climate Change will come out with a new report — the last one was in 2007 — that will provide a new baseline. The NPCC has to look at it and say, “that’s the international consensus. How does that trickle down to us?”

GG: Beyond the FEMA data, are there any other key results from Sandy, particularly at the city and state level?

KJ: That whole discussion about the barriers has taken front seat. The mayor and the governor are not necessarily seeing it in the same way. My impression is that the mayor is much more circumspect and realistic about it … He has advice from the panel and task force. There are serious concerns about the barriers. They are very appealing as a quick fix. It’s a simplistic approach. But life is not that simple.

Many of us advised the Mayor’s Office of Long Term Planning and Sustainability. I’m also a technical advisor to the Department of City Planning. They are going about it in a much more holistic way. Barriers are an option in a portfolio of measures. The advisory panels were established before Sandy and they are continuing with their efforts. Sandy has provided very important data to verify certain notions that already existed from the NPCC and other studies. There were forecasts as to where the water would go and how high. We have seen it can go higher …

The governor jumped on the idea of barriers immediately. Congressman Jerry Nadler wrote a letter three or four months before Sandy to the Mayor’s Office of Long-Term Planning to produce a study of barriers. There were other politically motivated voices pushing in that direction. There is another barrier lobby — Dutch engineering firms. They smell a big job. Ever since Katrina, they have been roaming around the city with the help of the Dutch consulate general. I’m a little bit of a barrier skeptic and a thorn in their skin. [He laughed at this.]

GG: You have said publicly that you don’t see storm barriers as a long-term solution.

KJ: I do not deny that they have a medium term benefit that’s very attractive. Storm surge barriers are very good at keeping out the high water during storms, combined with high tides, because they have a certain height. Assume we have 5, 6, 8, 10 ft sea level rise. You could build barriers against that if you have enough money … Let’s take $30 to 40 billion. Make them high enough, you could keep storms out for 100 years.

That’s very good news … Not only in New York City, the whole Hudson Valley and the MTA, with all its assets that are on the protected side. But not any assets out on Long Island. Just outside the barriers it gets a little worse, during storms, when the barriers are closed, the water piles up on the outside of the barriers. Connecticut will not like it. Long Islanders will not like it. New Jersey outside the barriers will not like it … The communities south of Sandy Hook.

Or, if the big barrier from Sandy Hook to Rockaway is not built … Then it may be three smaller ones near the Verrazano and Whitestone bridges, and across Arthur Kill. Then, the people in the outer harbor might not like it. Because that’s where you get an extra 1 to 2 feet storm surge rise. These are local difficulties. But barring those — that’s not my issue. Also barriers will become a political playball that will delay their building. There will be lawsuits … A West Way dejas vus.

My real concern has to do with long-term sea level rise. The barriers are mostly open — the sea level will get in and out of those barriers. Once sea level rise reaches about 6 to 10 feet … You can’t keep the sea level out (using the barriers) … Because the Hudson brings its water down. You have to get the Hudson water out into the ocean, otherwise the barriers are working the opposite way, they would fill up from behind … It’s not just the Hudson. It’s the Passaic, the Hackensack, the Raritan. All this inland water has to get out into the ocean.

You have two options: Either you open the gates and let the ocean in and equalize, or you have to pump out this river water and keep the ocean out all the time. We would become essentially like New Orleans, which has levies and dikes around it. They are below sea level and rely on huge pumping systems to keep out the water from the higher Mississippi and the ocean. They pump it out all the time. 24-7/365. Those systems have to work all the time. To do such a pumping system for New York — that would produce a lot of greenhouse gases. It’s another reason why this is unsustainable.

GG: What does such a pumping system do to the natural ecosystem?

KJ: We don’t know. We haven’t done any studies. That’s why I think the Mayor is smart. He understands the issues. He realizes that solving all of these problems, and others still coming out for barriers and their environmental impacts that will be unacceptable, will take 10 to 20 years. He wants to do something that’s doable now, and that’s doable on the nickel of the city. Rather than wait for federal money raining down and hoping for the best … and having NYS, NJ, CT and almost 300 jurisdictions agree to a big plan for a delta works …

GG: So you’re saying that the barriers don’t address the core issue?

KJ: The ocean will rise to the point where it will encroach certainly on the neighborhoods out in Breezy Point, Newtown Creek, parts of Manhattan, Jersey City... Current discussions on barriers miss the boat: sea level rise. I don’t know why that’s not under discussion.

That’s what your article has to point out: Folks, you’re missing the big picture. You’re fiddling around on the edges — the scary edges of stormy days… The barriers will be effective only for the scary edges …

But my concern doesn’t become effective until sea level rise reaches 4, 5, 6 feet or more. And it will effect gradually first the lowest-lying areas, and then gradually go up …. That’s where all those regulations — the ABFEs — come in. There’s a lot at stake right now: how the city wants to shortcut the red paper for rebuilding quickly now, while on the other hand look to the future and insist on rebuilding at higher elevations (and other protective measures).

GG: What does the latest data say about sea level rise relative to New York City?

KJ: The NPCC came out with two forecasts. One was based on IPCC data, which essentially had 2 feett of sea level rise by the end of the century. But with a footnote. It leaves out the ice melt in Greenland and West Antarctica. Knowing that shortcoming of IPCC, the NPCC came out with a second model that did the best we could in taking into account historic geological sea level rise rates that have occurred at the end of glaciation times, and took other projections from satellite measurements for this second scenario. That is called Rapid Ice Melt Scenario — RIMS. It has 2 feet of sea level rise by the mid-50s; 4 feet by the mid-80s; and if you project to 2100, it’s essentially 5 feet, plus/minus 1 foot by the end of the century.

If you take the 6 feet from the RIMS, which I personally think is the more likely value, that’s when the barriers become dysfunctional. Once you have 6 feet, you start to inundate a lot of areas, particularly if you have weather on top of that. The new BFEs will have to be updated twice between now and the end of the century to keep up with sea level rise.

GG: Of all the impacts of climate change discussed in the NYS Climate report — severe weather, heat waves, etc. — is sea level rise the core issue?

KJ: Yes. Sea level rise is the ultimate fate of the city. The heavy precipitation, heat waves don’t challenge the existence of the city. Sea level rise gets at the jugular. It truly threatens the livelihood of the city as we have it now — unless it adapts. It can adapt. It can be a totally lively city without barriers. We are lucky. We have high ground within our boundaries. Neither New Orleans nor Amsterdam nor Venice have that luxury. We have that luxury. We just have to move together on higher ground.

Unfortunately, Jane Jacobs may not like it. We may have to modify some of our low-rise neighborhoods and make them higher-rise neighborhoods. At least we have that option. We better do it in the form of a planned, managed retreat, rather than chaotic reactions to the Sandy’s of the future. That’s where urban planning comes in.

That hasn’t sunk in yet, even with the forward looking folks in the Mayor’s Office of Long-Term Planning and the Department of City Planning. They still think in decades, instead of a century or longer.

GG: Where is the city in terms of thinking about the rest of the 21st century?

KJ: I’m kicking them left and right. It’s like moving mountains.

GG: Will all Zone A areas eventually have to be evacuated?

KJ: Not wholesale. Many of them will be evacuated and transformed into a nice waterfront, green parks, more than we ever had asked for. There’s a wonderful future to be seen. It’s an incredible opportunity for NYC. Those structures and buildings that we want to keep there — there are several options … The Customs House (in Lower Manhattan) could be lifted up. Or, cheaper, you just give all this basement stuff up. Waterproof it, etc., and take out all the electric control systems from the basement of that building … put them up on the roof, or the 10th floor … that’s a small price to pay.

GG: What about all of the buildings that are owned and operated by the NYC Housing Authority in these areas?

KJ: Let’s take the public housing in Red Hook, which is in bad shape after Sandy. They still have boiler trucks outside … I guess theoretically you could lift them up, but I think it would be cheaper to build new ones if you insist on having structures like them at such locations. It would be much better to find a place within the five boroughs to create new public housing that’s safe. All the houses that were built out on Coney Island and the Rockaways, it’s so unsustainable.

All that stuff that was built north and south of Newtown Creek, the waterfront of the East River … These were all plans that have been in the works for 10 to 20 years. At that time, nobody had any idea that sea level rise and climate change would play into it. Same thing with Willets Point, Hunters Point and all these development projects ... Look at the Westside Yards.

Our institutional inertia is 10 to 20 years out of pace with our climate knowledge. Unless we make changes — that’s in the hands of the mayor. He can whip those plans into shape. He’s treading too slowly on incorporating those changes, I think.

GG: Where is the mayor’s inertia coming from? Is it intellectual? Is it pressure from the real estate industry?

KJ: It’s everything. They all work in the wrong direction. We are all in risk denial. I am sometimes in risk denial. It starts with the individual, then come the institutions, and then come short-term interests like the real estate industry … Developers hold onto risk only for the time it’s in development, and then they sell it to whoever buys it. The risk is transferred to the new owner … There’s no law that tells the developer to tell the new owner what the risk is, or — more consequential — (that he or she is) liable for it.

GG: You have stated that the thrust of PlaNYC was not to prepare for climate change, but, rather, to plan for a projected one million new residents by 2030.

KJ: Everything else was an afterthought, which was pushed by the scientific community … (Climate change) was patched on to it. It wasn’t the original motivation for it … The updated plaNYC that came out three years later faced climate change much more upfront, but still only in a short term way. If you read the language, you see it was not written by scientists. Why should it be? For instance, there are sentences in there that say we have a fixed amount of land and we have to make better use of the land. We don’t have a fixed amount of land. It’s being reduced (by sea level rise). That wording is wrong. The thought is wrong. Intellectually it hasn’t sunk in.

GG: Are you saying that the operating premise for PlaNYC has to be different? For instance, how do we plan for a potential 6 foot sea level rise at the end of the century?

KJ: And it doesn’t stop at 6 feet at the end of the century. It will accelerate for at least 200 years. Maybe in 500 years, it will start to level off if we get a Kyoto-like protocol. Which we still don’t have. So this city will have to live with an ever smaller footprint. And we can tell roughly where it’s going.

Maybe future generations will come up with some smart way of carbon sequestration … But it won’t affect sea level rise for another 500 years … Because we have front-loaded so much CO2 into the atmosphere … By all likelihood, we are locked into sea level rise for a long time.

The density patterns of the city will have to be changed. We will have to move together on the high ground we have, and hand the filled-in lands at the edge of the city back to the sea. Yes, we are a waterfront city — but with the luxury of high ground. There will be losers. There will be winners.

___

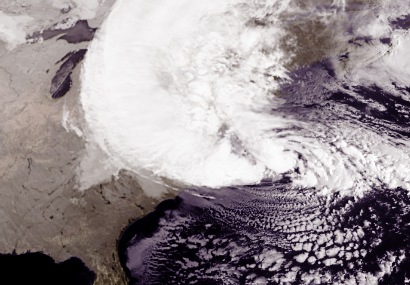

Photo of Sandy from NASA.