What Do Budget Cuts Mean for the DEC?

Is the state’s lead environmental agency adequately resourced? Department of Environmental Conservation (DEC) Commissioner Joseph Martens says that after a series of severe cuts in which the agency lost 20 percent of its staff, he does not expect to be hiring in the foreseeable future. Referring to the condition of the state’s finances, Commissioner Martens told the Gotham Gazette, “We are trying to adjust to that new reality. I don’t think we can think about adding resources anytime soon.” Commissioner Martens stressed that the DEC has not lost additional staff since Gov. Andrew Cuomo has been in office, and that this year’s budget added resources for badly needed DEC capital projects.

Sixteen months ago, representatives of some of the state’s leading environmental organizations wrote an open letter to then New York gubernatorial candidates Carl Paladino and Andrew Cuomo. The letter referenced “long-standing problems that are now endemic to New York State’s efforts to protect public health, provide stewardship of our lands, and prevent our air and water from being polluted.” It described the condition of the DEC as “dire” due to disproportionate budget cuts and the loss of almost 800 agency scientists, engineers and enforcement officials in less than four years. The letter also discussed the “slashing” of the state’s Environmental Protection Fund by 40% in 2010. According to the signers, the Fund’s diminishment left “municipalities and non-profit groups waiting for payments to support ongoing efforts to protect drinking water, reduce solid waste, and improve the quality of life in New York’s communities.” State support for the Fund has remained at the 2010 level of $134 million.

After his election, Cuomo went on to name one of the letter’s signers, Open Space Institute Director Joseph Martens, as the new DEC Commissioner. Conversations in the last few weeks with several of the letter’s signers, along with elected officials, and others who work with the agency, revolved around one central question with no easy answer. Can the DEC sustain its enormous and critical mission with its current level of resources? And if it cannot fully sustain the mission, what is the potential long-term impact on the State’s natural resources and public health? Indeed, a number of environmental advocates argue that as the agency’s resources have shrunk, its responsibilities have only increased because of additional state and federal legislation, population growth, and long-term environmental challenges like climate change. Paul Gallay, President of Hudson Riverkeeper and a DEC staffer for ten years, asserts that the DEC is on a "starvation budget." "The job has gotten bigger and the budget is smaller... remember, the term environment covers hundreds of different aspects of our quality of life and public health."

Martens points out that, despite prior staff losses, the agency has had significant accomplishments in the last year, including passage of legislation regulating large-scale water withdrawal from state rivers, lakes, streams and groundwater. Environmental groups have hailed this legislation and the DEC’s role in bringing it to fruition. But these same groups, the union representing DEC professional staff and some elected officials argue that the DEC is being asked to do too much without sufficient resources.

An Expansive Mission and New Challenges

“This is an agency with an enormous mission”, says Richard Schrader, the National Resource Defense Council's legislative director. The agency’s mission is to “conserve, improve and protect New York's natural resources and environment and to prevent, abate and control water, land and air pollution, in order to enhance the health, safety and welfare of the people of the state and their overall economic and social well-being." The DEC’s structure speaks to the breadth and depth of the agency’s mission. Six programmatic “offices”, housing 10 divisions and other dedicated units, oversee the state’s air and water resources, environmental permitting functions, environmental remediation and materials management needs, enforcement of environmental regulations, and management of natural resources such as forests and marine areas. This does not include the agency’s administrative and operational divisions. The DEC’s responsibilities include everything from monitoring and reducing air pollution to inspecting sewage treatment plants to the upkeep of state-owned hiking trails. Commissioner Martens points out that the DEC “touches an enormous variety of New Yorkers’ lives”.

A serious challenge for the DEC and state environmental policy in general is that environmental conditions are shifting, and will continue to do so. The DEC houses special offices focused on emerging issues such as climate change and invasive species. Its public protection office includes a law enforcement division and an emergency response unit. Schrader described the agency’s performance during the flooding caused by Hurricane Irene as “very impressive”. He noted that emergency relief work is another “redefining of the agency’s mission”. Commissioner Martens was on hand as DEC staff worked in the field during Hurricane Irene and commented that, “the staff was extraordinary. Anytime we’ve asked the staff to do something, they’ve responded.”

Because New York is seeing more illustrations of the impact of climate change, the agency is promoting energy efficiency and sustainable development throughout the state via programs like Cleaner Greener Communities. The DEC also manages regulatory responsibilities connected with New York’s participation in the Regional Greenhouse Gas Initiative, a carbon trading program among nine U.S. states. Income from the initiative is reinvested in renewable energy projects.

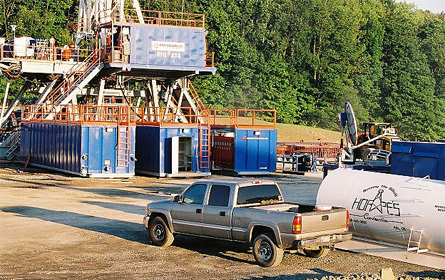

Another key challenge for the DEC is that it is considered an important part of realizing the Cuomo administration’s economic development objectives. The Cuomo administration sees both environmental protection and wise stewardship of New York’s wealth of natural resources as inextricably linked to economic revitalization. An environmental policy overview released by the governor before his election argues that the state cannot afford to address environmental challenges in a vacuum. This statement has particular resonance given the state’s financial condition. A dual mission of environmental protection and economic development creates enormous opportunities for the DEC, and profound challenges. Nowhere is this more apparent than in the administration’s plan to open the Marcellus Shale to hydraulic fracturing. The DEC has stated that they will require an estimated 225 additional staff to adequately oversee drilling in the Shale and protect the state’s water resources. The Cuomo administration is exploring whether additional fees charged to the gas industry could be used to support new DEC staff.

Robert Moore, Executive Director of Environmental Advocates, a non-profit group that monitors the DEC, questions the rationality of hiring 225 people to service one industry after 800 staff cuts. He also asked whether revenue for the agency could be increased by reviewing its overall fee structure. Mr. Moore maintains that while environmental and economic successes are not diametrically opposed, the DEC has one core mission. "With regard to fracking, the Governor and the DEC initially erred by buying into industry claims of economic benefits rather than focusing on the science. Job creation is not DEC's job, environmental protection is."

The DEC is actively involved in the state’s economic life as a regulator, provider of technical assistance and an economic engine. The agency manages natural resources, such as forests and fisheries, which are vital to the state’s economy. The DEC’s capital projects have the capacity to generate economic activity and support future investment. This year’s additional capital funding for DEC will be used for coastal erosion and flood control projects, and dam reconstruction. The $102 million allocated to the DEC is part of $1 billion being spent statewide via the New York Works program. According to Martens, the DEC is also considering implementation of a program currently used by the Federal Environmental Protection Agency that encourages businesses to self-audit their processes in exchange for technical assistance with pollution prevention. The Cuomo administration has expressed a general interest in finding ways to link environmental regulations and business incentives.

Responding to Limited Resources

When asked about agency priorities in 2012 and beyond, Martens explained that the DEC is in the process of evaluating how agency services can be improved given current budget constraints. The agency’s permitting functions are an area where Mr. Martens believes real strides can be made, and the agency plans to review every permit program (from wastewater discharge to wetlands protection) in the next two years. He notes that DEC “technology badly needs upgrading but we have embarked on an initiative to increase how we can use the technology we have to increase efficiency in our processes.” Martens argues that both the ability to file electronically and a re-design of the permitting process can make up for some of the agency’s staff loss. “A lot of the processes can be simplified and staff can do more program work.” This approach is echoed in Cuomo’s New NY Agenda, which proposes “a comprehensive review of the existing environmental bureaucracy” and “recommendations for reorganization and better coordination where such coordination would provide for significant cost savings, better management or more efficient operations”.

Three DEC staff members who are familiar with the agency’s permitting programs commented anonymously that while a rethinking of the agency’s permitting process is inevitable given resource limitations, the fundamental objective of permit review should not be compromised. They made the point that no matter how quickly applications can be submitted, a qualified staff person must be available to thoroughly review the application, and determine if relevant information has been withheld. They argued that the agency simply does not have sufficient staff people at present to carry out compliance and enforcement responsibilities which are needed after permits are approved. They also questioned the agency’s use of both contractors and state employees to carry out permit review functions, pointing out that contractors are not necessarily subject to the same ethics requirements as state employees.

Measuring the Impact of Staffing Cuts

The DEC’s 2,983 employees who are responsible for carrying out the agency’s mission and programmatic objectives are situated in an Albany central office and in nine regional offices throughout the state. Agency staffing levels are at their lowest point in over 20 years.

Assemblyman Robert Sweeney (D), chair of the State Legislature’s Environmental Conservation Committee believes that staffing losses have impacted the DEC on a variety of levels, including its ability to monitor air and water quality, process permits and even file applications for additional federal funding. “Everything has been impacted and nothing has been abandoned…they are hurting very badly and their employees are showing extraordinary dedication. They’re not getting the resources. We’re not talking about a small number of positions. Their needs are very significant.” Assembly Member Sweeney’s counterpart in the State Senate, Environmental Conservation Committee chair Sen. Mark Grisanti (R), adds that “the DEC has basically been cut to the bone. The biggest challenge is getting the DEC to the levels it needs”. As to whether Governor Cuomo sees the agency as a high priority, he responds, “the Governor totally recognizes the importance of the DEC. I think that he gets it.” Representatives of environmental organizations interviewed for this article had varying opinions on the priority that the Cuomo administration places on the DEC’s resource needs. The Cuomo administration did not respond to requests for comment.

There is not complete agreement that restoring some of the DEC’s lost staff capacity is what the agency needs to fulfill its mission. Darren Suarez, Government Affairs Director with the Business Council of New York State, argues that “the agency has significant resources. The DEC has been evaluating how they’re using their resources. They’ve recognized that they can’t operate as they have in the past. You can’t just throw additional staff at the problem…the DEC has committed itself to lean management.” He notes that there are technological solutions that could be used to help address some of the DEC’s responsibilities, such as remote monitoring of wastewater discharge, and believes that the permit review process “had become duplicative”. Suarez “sees no indication” that the agency cannot fulfill its mission of protecting human health and the environment. And he believes that the DEC has recognized that they can do more to work in a collaborative manner with business, and not forego regulatory requirements.

None of the environmental leaders who sounded the alarm about the DEC 16 months ago were prepared to argue that the state’s environment had markedly deteriorated due to loss of staff at the agency. In fact, they highlighted a number of the agency’s accomplishments over the last year and the impressive performance of DEC personnel. What they shared was a sense that the agency was no longer operating at full capacity because it lacked sufficient manpower. Marcia Bystryn, President of the New York League of Conservation Voters, maintained that “there is no reason to believe that anything catastrophic has taken place.” But she added that DEC’s staffing constraints “have slowed things down”. Paul Gallay at Hudson Riverkeeper adds, "we are slowing down on the progress we made in past decades. Sooner rather than later, we could come to a dead stop and then go in reverse. You don't want to get to that point." Sweeney was perhaps more pessimistic. “It may not be obvious that the air quality is worse, or that the water quality isn’t what it should be, but that doesn’t mean there isn’t a problem… Unfortunately DEC is not out there in the field as much as they were in the past and should be in the future. Their ability is compromised.”

Martens agrees that there were “real concerns about whether we could handle and continue with our basic functions, and keep our mission…(but) things have stabilized here. I still have a great deal of confidence in our ability to maintain and improve water quality for instance.” He cites an agreement signed last week between DEC and New York City’s Department of Environmental Protection that will reduce the flow of sewage into the Hudson River, East River, Newtown Creek, Gowanus Canal and other city waterways. The enforcement order is the result of two years of work by DEC’s water division. Commissioner Martens adds, “I don’t think we have lost ground. We’ve made progress.”

We will be looking at specific areas where advocates have raised questions about DEC capacity, including monitoring of wastewater discharge and air quality, and the agency’s ability to respond to oil and chemical spills, in a follow-up article.

Is the DEC Prepared For Hydraulic Fracturing?

While the Cuomo administration has not been definitive about its plans for hydrofracking recently, it is also unclear whether the state is adequately prepared to manage natural gas drilling and protect local drinking water supplies.

The Governor declined to mention drilling in the Marcellus Shale when he made his State of the State address on January 4th despite the fact that the written version of his address discusses hydraulic fracturing in the state’s Southern Tier, where the largest deposits of natural gas are believed to exist. The state’s 2012 budget does not include revenue or costs related to hydraulic fracturing activity. The Department of Environmental Conservation (DEC), the state agency that would issue drilling permits and oversee drilling related activity, received a 9% funding increase in 2012, but no allocations for new staff. The Cuomo administration did not respond to several requests for comment for this story.

The DEC is now required to review over 46,000 statements on hydrofracking received from the public and local governments, and release a finalized regulatory framework for drilling which will likely face legal challenges. Public comment on the state’s revised hydrofracking impact report and drilling regulations was extended until January 11th due to the volume of statements submitted. The Draft Supplemental Generic Environmental Impact Statement (SGEIS) outlines the Cuomo administration’s plans to open the New York State portion of the Marcellus Shale to natural gas drilling. Drilling in the Marcellus Shale will require hydraulic fracturing, a technique that is controversial for environmental and public health reasons. Proponents argue that drilling in the Shale will create thousands of jobs and help to revitalize the upstate economy.

According to DEC Director of Public Information, Emily DeSantis, “If the final documents determine high-volume hydraulic fracturing could move forward in New York, we could begin to review permit applications after the final SGEIS and findings statement are released.” DeSantis expects the final documents to be released this year.

While the state has taken steps to minimize the possibility of large-scale water contamination, such as drawing 4,000 foot no-drilling boundaries around the Syracuse and New York City watersheds, activists and some residents contend that the state is not yet prepared to adequately protect underground and surface water supplies from the scale of drilling that is planned. The union that represents the DEC’s scientific, technical and professional employees, the Public Employees Federation (PEF), along with some elected officials, has echoed this concern.

Properly Staffed?

According to the DEC, the agency has shed 800 employees, from both professional and non-professional categories, in the last 3 years. The PEF reports that the DEC currently has 3,003 employees, which represents a 21% reduction in staff since 2008.

DEC spokeswoman Emily DeSantis points out that “from the start we have recognized the need for additional staffing to oversee high-volume hydraulic fracturing operations. Our estimates indicate we will need about 140 staff in the first year and 200 staff by year 5.”

Wayne Bayer, a member of the Public Employees Federation Executive Board and a 30-year veteran staff member at DEC headquarters, tries to illustrate the resources challenge that the DEC faces in properly regulating hydraulic fracturing. The agency will require an influx of specialized staff in several divisions including water, mineral resources and environmental remediation, within both DEC’s central and regional offices. The DEC will need additional engineers, geologists, chemists, wildlife biologists, inspectors, attorneys and administrative staff.

According to Bayer, DEC personnel will be responsible for everything from reviewing drilling applications, to checking the strength and width of the cement encasing drilling wells, to monitoring the withdrawal of hundreds of thousands of gallons of fresh water used for drilling and ensuring that private wells and public water supplies are not diminished, to evaluating the impact of drilling activity on endangered species and local forests, to cleaning up waste water spills as they occur.

The DEC projects that as drilling in the Shale progresses, it may receive as many as 1,600 permit applications per year. Drilling in the Marcellus Shale could continue for 30 years. The state envisions annual construction of a minimum of 413 horizontal and vertical wells in a “low-development scenario”, and 1,652 wells constructed annually in a “medium-development” scenario. At present, the agency has sixteen professional staff assigned to oil and gas regulation including permitting, compliance and enforcement across the state.

Aside from the question of hydraulic fracturing, there is concern that the DEC is no longer able to fully carry out its existing responsibilities due to budget cuts. After Governor Paterson ordered 209 staff cuts in October, 2010, nine environmental organizations, including the New York League of Conservation Voters and the Nature Conservancy, issued a joint statement that “the latest round of layoffs will reduce agency staff to the lowest levels since the 1980’s, with serious consequences for the DEC’s ability to respond to environmental hazards, not to mention critical routine functions such as monitoring air and water pollution, as well as natural resources protection and stewardship.”

Wayne Bayer notes that the DEC has fallen behind on issuing new and renewal permits for industrial sites as part of its mandate to monitor the state’s water and air quality. DEC just worked its way through a year- long backlog of required inspections of chemical bulk storage tanks with the help of private contractors. The agency is also behind on rewriting regulations for chemical and petroleum bulk storage because of staffing shortages in the Office of General Counsel and in the Environmental Remediation program, according to Bayer.

Consequently, the Public Employees Federation is telling lawmakers that the current moratorium on hydraulic fracturing should continue until it is certain that the DEC has adequate staff. Doug Curella, Chief of Staff for Senator Mark Grisanti (R), Chair of the State Senate Environmental Conservation Committee, concurs: “It’s important that the DEC is properly staffed before we begin the conversation. They have historically lost a lot of staff.”

Where is the Money?

How will the state pay for new staff and other resources needed to manage hydraulic fracturing in the midst of a budget crisis? The DEC says that the Governor’s advisory panel on hydraulic fracturing is looking at ways the state can generate revenue from the gas industry, including fees and possibly a severance tax. Emily DeSantis adds that, “we have repeatedly said we will only review the number of permits that we can responsibly oversee given staffing levels.”

This position was echoed by Cherie Messore, spokesperson for the Independent Oil and Gas Association of New York (IOGA), an industry trade association. When asked about DEC’s capacity, Messore responded that “the DEC will only grant as many permits as can be prudently and responsibly supervised. And we’ve always been an advocate for the DEC to be properly staffed to be able to do its work well.”

Messore said that the association was not in a position to comment on the Cuomo administration’s exploration of taxing the oil and gas industry to raise revenue. Accurately assessing the impact of targeted taxes or fees on the state’s budget may not be a simple matter. Assemblymember Richard Gottfried (D), Chair of the Assembly’s Health Committee, points out that “since dollars are fungible, it’s always hard to measure whether dollars from a special tax are used to pay for staffing, or just to replace dollars that were lost.”

As the environmental review process continues and questions mount, is hydraulic fracturing becoming a political liability for the Cuomo administration? Democratic Assemblymember Robert K. Sweeney, chair of the State Assembly’s Environmental Conservation Committee, told Gotham Gazette, “It has been a political problem all along and it is becoming more so all the time. I have colleagues who are having second thoughts about the whole thing- the opposition is growing steadily and is more vocal. The potential problem for the administration is that the first time something bad happens –and something bad will happen- it will reflect directly on the Governor.”

Public hearings last November on the draft report and drilling regulations attracted 6,000 attendees and standing room only crowds both upstate and downstate. Drilling opponents visibly outnumbered supporters at the Sullivan County and NYC hearings, and The Wall Street Journal reported that opponents outnumbered supporters by 4 to 1 at a large hearing in Binghamton, which is situated in the Southern Tier.

The oil and gas industry maintains that the Governor’s plan has strong support among hard hit farmers and other landowners in the Southern Tier. Cherie Messore of IOGA observes that “when you look at the most recent polls, they are definitely very split. The areas that will be most affected by hydrofracking, in the Eastern-Southern Tier of the state, are the most supportive. People are seeing the jobs and prosperity and the good things that are happening in Pennsylvania. We’d like to see that prosperity come into New York State.”

What will the DEC determine after it absorbs the 46,000 comments it received from New Yorkers regarding their views on hydraulic fracturing? And can the DEC comprehensively manage hydraulic fracturing and protect the safety of the state’s drinking water at the same time? Scott Reif, spokesman for the State Senate Republicans, asserts that “If it can be done safely and responsibly than (Senate Leader) Dean Skelos would support it. Every indication is that the DEC can do it.” When asked if he could specify what “every indication” meant, Reif replied, “If the DEC believes that they can do this, then we are supportive.” Assemblymember Robert Sweeney is less certain. “The Governor has oversight of the DEC. The Legislature has oversight. They feel that they have some handle on it. One can only hope that if the time comes, the DEC will be prepared.”

The Council Tackles Corporate Personhood, Transparency, and the Budget

The City Council got the Occupy Wall Street treatment today during their debate on a resolution that will support ending corporate personhood

Approximately 20 supporters of the resolution — which OWS asked supporters to attend City Council for via social media the day before — cheered on the bill, while dissenting Councilmen were booed and hissed from the observation balcony during the Council’s debate. Resolution 1172 expresses the Council’s support of the U.S. Congressmen who are seeking to overturn a Supreme Court decision that said that corporations and people share the same free speech rights and with it, the unrestricted ability to lobby politicians. The City of Los Angeles recently passed a similar bill.

Corporations can't "laugh or cry," said the resolution’s sponsor Councilman Brad S. Lander speaking on the Council floor. "It's not an issue of left or right, it's an American issue."

Though Occupy Wall Street has certainly garnered the issue more attention, Lander told Gotham Gazette the Council’s interest in corporate personhood predates the Occupy movement.

Councilman Eric Ulrich spoke against the resolution.

“Corporations are people. All their money goes back to the people,” he said, before being hissed and booed by onlookers so much that Council Speaker Christine Quinn extended his speaking time.

The vote was mostly along party lines with 41 yes-votes from Democrats, five no-votes from all five Council Republicans (Councilmen Dan Halloran, Vincent Ignizio, Peter Koo, James Oddo, and Ulrich), and one abstention from Councilman Peter Vallone, a Democrat.

The Road to Transparency

The Council again voted to empower New Yorkers by increasing transparency.

Following last month’s vote to notify parents and employees about testing for the dangerous chemical PCB in schools, the City Council voted unanimously today to give New Yorkers “TIPS” — Transparency In Paving Streets — which requires the Department of Transportation to disclose information on their rating of city streets, the dates of past repair and pavement, and plans for future repaving.

Speaker Quinn noted that Community Boards rank streets and areas in New York that need to be addressed and report to the DOT. Transparency about how city streets are ranked and when they were last paved is crucial to helping citizens advocate for their own streets Quinn said.

Budget Balancing

In the first stated meeting of the New Year, the Council also rejected three of the Mayor’s proposed budget cuts for the Fiscal Year 2012 budget.

The first rejected cut was a $730,000 cut to the Office of the Chief Medical Examiner which the Council says would have created delays in processing DNA tests in rape test kits and other forensic evidence in criminal proceedings. The other rejected cuts were a 1.5 million cut to the New York City Health and Hospitals Corporation’s operating subsidy, and cuts to two after-school programs.

These cuts would have had a “very negative impact on New Yorkers,” Quinn said.

The sole dissenting vote against the passage of the Mayor’s budget cuts was Councilman Charles Barron who criticized the Council for approving layoffs and attrition job cuts and criticized his colleagues for supporting the “99 percent” on the street but voting against them “inside [the Council Chambers].”

The approved budget includes hundreds of job cuts to the Departments of Sanitation, Cultural Affairs, and Health and Mental Hygiene.

Also On the Agenda

The Council also passed a bill that will regulate the sale of carpets, ensuring that there are no harmful chemicals in carpets sold or installed in New York City. These chemicals, which contribute to “sick building syndrome” are said to affect 30-70 million Americans.

The Council also voted on three resolutions that call on the Congress to further regulate gun control in the United States.