How the City Has Reduced Soot

The New York State Department of Environmental Conservation recently predicted that the downstate region of New York State (including all of the city, plus Long Island and the lower Hudson Valley) soon will meet the federal annual health standard for soot (a.k.a. fine particulate matter), for the first time ever.

This prediction came in the department's draft plan, released last month. It is good news for anybody who breathes - and it's worth understanding what is working and what isn't.

Why "Particulate Matter" Matters

Public health experts agree that this kind of soot pollution is one of the most dangerous forms of air pollution. In the U.S., tens of thousands of premature deaths are attributable to soot pollution annually. Roughly 4,000 such deaths occur in New York City every year.

Soot pollution creates real-world impacts beyond statistical premature deaths. Dozens of studies have shown that soot particles trigger asthma attacks and emergencies, bronchitis, cancer and heart disease. Plus, the black carbon core of many soot particles has been linked to global warming and especially related to melting sea ice in the Arctic. In fact, some scientists believe that this black carbon may be the second most important global warming pollutant after carbon dioxide.

How the System Works

Under the federal Clean Air Act, the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency is required to set "National Ambient Air Quality Standards" for six common, so-called criteria pollutants. Besides particulate matter, these include ground-level ozone, carbon monoxide, sulfur oxides, nitrogen oxides and lead. These standards are health standards - in other words, EPA sets the limits based on its best understanding of the effects of pollution on human health and environmental welfare. To arrive at this, the agency uses scientific criteria and periodically reviews the most up-to-date literature. EPA does not look at technical feasibility or costs in setting these standards (those only come into play when the states devise strategies to meet the standards).

Once EPA sets its standards, states have to monitor their air quality. If an area fails to meet the standard, the EPA designates it is as a "nonattainment area," which triggers a legally enforceable obligation for the state to create a plan to reduce the pollution on a set timetable. If a state ignores this obligation, it risks losing the right to control its own pollution and could face extra pollution hurdles for any new industry. In extreme cases, a state could even lose its federal highway funding.

In 1997, EPA set its most recent standards for annual and daily exposure to fine particulate soot. These standards limit our exposure to particles that are no larger than 2.5 microns in diameter. To get a sense of how small these particles are, about 70 of them could stretch across the width of a single human hair. The particles are so small that they can easily evade the defense mechanisms of our noses and throats, and lodge in the deepest depths of our lungs.

How is NYC Meeting the Standard?

The Clean Air Act allows states to figure out the best, most cost-effective ways to cut pollution in their own air. Strategies that work best in Houston or Los Angeles may not work well in New York or may not be the cheapest way to achieve the desired pollution reductions.

Here in New York, diesel pollution lies at the heart of our soot problem. Back in 1995, the state Department of Environmental Conservation identified diesel engines as the source of more than half of the particulate soot pollution breathed by New Yorkers on the sidewalks of Madison Avenue. This led to a broad campaign to clean up the buses in New York, and for the EPA to adopt cleaner federal standards for new diesel engines.

In 1998, EPA adopted new standards that would cut diesel pollution from new engines by 40 percent, starting in 2004. (Thanks to a consent decree in litigation against the nation's engine makers, these cleaner engines hit the market in October 2002.) By 2000, the state agreed to clean up the Metropolitan Transportation Authority buses, with a comprehensive program to use a cleaner, ultra-low sulfur diesel fuel; retire the oldest buses and replace them with the cleanest, new buses available; and to retrofit the remaining buses with advanced soot-busting filters.

The clean-up of the MTA New York City Transit fleet has been a smashing success. Today, the fleet emits 97 percent less particulate soot pollution than it did in 1995, when the Natural Resources Defense Council ran ads on the buses that read "Standing behind this bus could be more dangerous than standing in front of it." The fleet's early commitment to hybrid-electric buses was a smart bet against higher fuel prices that pays off with every mile. And, the fleet's clean-up program serves as a model for large city fleets around the globe.

The MTA program also helped lay the technical and political foundation for the national cleanup of diesel trucks and buses. EPA adopted new pollution standards for trucks and buses in 2001 that, in effect, nationalized the fuel and emissions goals of the MTA program: ultra-low sulfur diesel fuel for all buses and trucks, plus at least 90 percent emission reductions from all new engines.

The New York State draft plan for particulate matter shows that these programs to reduce diesel pollution are working. Since 2002, diesel soot emissions have been cut by 54 percent.

In contrast, the state's data show clearly that pollution from other sources has not decreased. "Point" sources (large facilities like refineries or power plants) and "area" sources (smaller sources that collectively add up to a lot of pollution citywide, like heating units in residential buildings) have actually gone up by almost 12 and 8 percent, respectively.

In other words, thanks to cleaner diesels, New York is on the path to cleaner, safer air.

New Yorkers cannot breathe easily yet. We still fail to meet the EPA standard for ground-level ozone (smog), which is highest in summer months. A city law that requires contractors to cut pollution from their construction equipment is being widely ignored, and few of the city's school buses use the most advanced soot filters to protect the children riding them. And, when EPA designates nonattainment areas for its daily particulate matter standard late next year, it's likely that New York will have to take further steps to reduce its soot pollution.

But for several years, it's been clear that New York -- and the diesel industry -- have been investing in cleaner diesel fuels and soot-cutting technologies. Now, for the first time, we can see the long-term data trends to confirm this, and the real-world benefits of these investments.

Â

Making Black Cars Green

Now that congestion pricing is behind us (at least for now), attention can turn to other PlaNYC 2030 proposals to lower the carbon footprint of some of the traffic we see every day in our city.

To do that, the Taxi and Limousine Commission recently approved regulations will increase the fuel economy of all new "black cars" that service the city's business community to a minimum of 25 miles-per-gallon (mpg) next year and to a minimum of 30 mpg beginning in 2010.

The proposal to green the city's roughly 10,000 black cars is an obvious follow-up to last year's regulation that is, slowly but surely, converting the city's yellow cabs to fuel-efficient hybrids, thanks to Local Law 72 of 2005.

Switching to more fuel-efficient models (whether hybrid or not) cuts fuel costs for drivers and operators, while reducing the global warming impacts of the overall industry.

Though this new regulation is well intentioned, it may not provide as much global warming as possible.

The Myth of MPG

Here's why: the use of "mpg" ratings (set by the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency for all cars sold in the U.S.) as the performance indicator is an imperfect way to measure the global warming impact of these vehicles. It's imperfect for two reasons.

First, the agency's mpg ratings are flawed because they are based on the agency's assumptions regarding the typical style of driving in cities and on highways across the nation. These assumptions bear no relationship to the way black cars are actually driven in New York City. To put it as simply as possible, EPA assumes cars drive faster, sit in less traffic, idle less, and use less air-conditioning than any city black car.

Second, mpg ratings are imperfect because there are significant, so-called "upstream" global warming emissions that stem from the manufacturing and transport of the vehicles to New York, as well as from the production, refining, processing and/or transport of whatever fuel is used (i.e., gasoline, diesel, biofuels, or alternative fuels such as natural gas or electric power). The agency's ratings govern only the amount of fuel that one can expect to use in typical city or highway driving, not the actual global warming pollution that comes from the driving (and the production) of the car.

A Footprint Approach

A more comprehensive approach would be to measure the full, life-cycle "carbon footprint" of the vehicles. Such an approach would ensure that the city is driving the black car industry towards the vehicles that provide the least amount of global warming pollution.

Of course, requiring car fleets to calculate their carbon footprint is a bit harder than simply reading the EPA mpg ratings. So, a practical solution would be to give fleets a choice: fleets could choose to comply with the regulation simply by using vehicles that meet the mpg threshold —- or they could use vehicles that provide, on a life-cycle basis, an equivalent or better carbon footprint. Providing this option would open the door to alternative fuel vehicles that may have very low upstream emissions, yet that do not meet the Environmental Protection Agency's mpg threshold of the regulation.

How could this work?

The city could add an alternative compliance mechanism to its newly approved regulations that allows (but does not require) fleets to use a full, life-cycle global warming analysis to demonstrate compliance with the new rule. With such an alternative compliance mechanism in place, a vehicle with low upstream impacts could comply with the rule, even if its mpg rating does not meet the 25 or 30 mpg threshold (or, as in the case of some vehicles that are retrofitted to run on alternative fuels, no EPA mpg rating at all).

Adding such a mechanism would move the city closer to the ground-breaking approach being proposed in California. In that state, regulators are considering a "low-carbon" approach to regulating fuels and vehicles, rather than regulating mpg or biofuels. The city should share California's goal: to encourage the fuels and vehicles that are the lowest in global warming impact on a life-cycle basis, rather than rely on the more-limited view of the miles-per-gallon of the vehicle, the amount of biofuels used, or the emissions at the tailpipe (all of which are used in various PlaNYC 2030 proposals).

Setting Standards

Lawyers reading this may say, "Wait a minute - the City cannot set its own emission standards."

That's right: only the Environmental Protection Agency and California can set emissions standards for vehicles, and other states can choose to follow them (New York tends to follow the more stringent California standards). But the approach summarized above would not run afoul of the federal restrictions on the city's ability to set vehicle emission standards, because it would not be a mandatory requirement on the fleets. Instead, it would simply be an alternative compliance mechanism that could be used by the fleets or not, as they wish. Thus, such a mechanism should comply with the federal restrictions on the city's ability to regulate vehicle emissions.

The Taxi and Limousine Commission deserves support for its plan to improve the environmental performance of the city's black cars.

Like the yellow cabs, these vehicles drive more miles, consume more fuel, and emit more pollution than other cars on city streets. However, the commission can make a strong plan even stronger by amending the final rule to enable fleets to use life-cycle analyses to unlock the potential of lower-carbon vehicles that could provide effective service in the five boroughs.

Rich Kassel is a senior attorney at the Natural Resources Defense Council, where he focuses on urban air pollution and transportation issues. He also chairs the Tri-State Transportation Campaign, a regional transportation advocacy organization and blogs on a variety of environmental issues on the NRDC switchboard.

Back to the Sustainability Watch homepage

Â

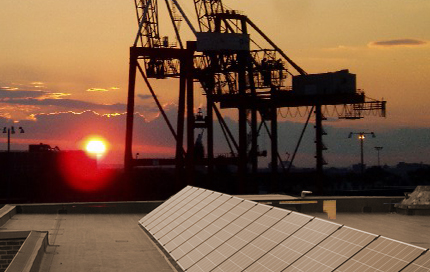

Blocking the Sun: Solar in the City

Looking out at New York Harbor from my window in Red Hook in Brooklyn, I imagine the water rising. Red Hook, before it was developed to handle the needs of a growing port in the 1800s, looked much like the wetlands of Jamaica Bay. It was a series of islands, some of which were below water at high tide. Global warming is a threat to the place, just as it is a threat to many low-lying areas of the city including the entire southern plains of Queens, Brooklyn and Staten Island.

Mayor Michael Bloomberg's PlaNYC notes that one way of reducing greenhouse gas emissions could be by moving from fossil fuel to solar energy. New Jersey and Long Island make solar power installation easy. Unfortunately New York does not offer much encouragement to the small homeowner who tries to convert to solar. On the contrary, it requires a permit process for rooftop installation of wind and solar systems that would make the old Soviet Union proud.

That said, living near the water forces you to take global warming seriously. So I set out to do my part by installing solar panels on my house. I imagined a project similar to stringing together a computer or stereo system would make me ready for the solar age and net metering. (Net metering allows daytime solar power to be moved to Con Edison's wires and nighttime power to be drawn from the system.) I was prepared to string a metal-sheathed cable from my roof to my electric meter and then plug a small windmill and solar panel into a DC/AC inverter and transformer. An electrician would then inspect what I did and wire it to my electric meter and I would be set. Total cost, I figured, would be $10,000 to $15,000 and while it would take some time for me to recover my investment, I assumed I would get there before the rising waters flooded my home.

The Rising Tide of Paperwork

What I found was a bureaucratic and featherbedding nightmare that could discourage the most ardent environmentalist. New York State Energy Research and Development Authority (NYSERDA), the city Department of Buildings, the Bureau of Electrical Control (whatever that is?), Underwriters Laboratories and Con Edison each have separate applications and work permits. A licensed architect must submit drawings. Three separate inspections of the installation must be made before the switch can be flipped. It has been reported that required approvals can take several years. The additional cost of all this government regulation more than cancels out the substantial tax incentives that government proudly provides in the name of encouraging energy independence.

Richard Klein operates Quixotic Systems, a small business that has installed more than 25 solar systems over the past three years. "Overregulation has brought the cost in New York up to the highest in the nation," Klein told me. "Government does not understand what a small business needs to develop a market or what a home owner can afford." Asked what can be done to make sustainable power work in New York City he quickly answered, "Consolidate permitting, streamline paperwork, have fewer entities involved."

The Energy Audit

For my project, I started with the New York State Energy Research and Development Authority. An agency representative at an Energy Smart Fair at Gateway National Recreation Area in Brooklyn told me the most likely way to reduce energy costs was by reducing the use of energy in my home. The state's Energy Research and Development Authority suggested an energy audit by one of their contractors. On the scheduled date of the audit, the contractor placed an airtight exhaust fan in my front doorway and began to measure places in my home where air was entering the building. They gave me good advice about insulation, promoted the Energy Star appliance program and noted places in my home that were not airtight enough. They told me that I had already made the big changes. The stove and furnace had electric pilot lights. The house was 99 percent compact fluorescent. All appliances except the toaster were Energy Star.

They followed up with a multi-page report. It concluded that I should replace three windows and a couple of doors and put down a new roof. Additionally, I should add some blow-in cellulose insulation to one corner of one floor of my home. The contractor's estimate for the work after tax rebates was $15,000. The work was eligible for tax rebates only if I did it with a certified contractor. My utility costs would be reduced by approximately $12 a month after work was completed. I can do the math.

There was no mention of solar or wind power in the report, even though I had mentioned them in my discussions with the contractor. In the end, the agency that should be promoting solar power throughout the state was silent.

Wind on the Roof

If it's so hard to install solar panels, how about wind power? Here in Red Hook the wind blows 24/7 for nine months of the year.

Small-scale windmills are not suitable for most New York City rooftops, but they also are discouraged by regulation. Installations of small rooftop windmills, even those that can be placed on a pole no more intrusive than a TV antenna, require the same permitting process that is needed to add a new floor to a building. There should be a way to develop a set of rules that says "yes, but" rather than "no, except."

There is much to look forward to in PlaNYC. New buildings will be constructed to be more energy efficient. Additional tax incentives will encourage rooftop solar. Green roofs and the use of succulent plants on specially designed roofs to reduce water flows to sewers are encouraged. Energy efficiency is promoted with new incentives. But PlaNYC must address the roadblocks presented by governments and utilities if we ever hope to see a significant move to renewable energy.

Looking down on Red Hook from the highest subway station in New York (the F line at Smith & 9th Streets), the bare black rooftops of the many buildings stretch to the waters' edge. There aren't even clotheslines on those roofs. Does everyone in the city use electricity or gas to dry clothes? PlaNYC says nothing about using rooftops to dry clothes.

Perhaps instead these roofs are the perfect place to build an ark in anticipation of the coming flood. I wonder how many permits are required.

Dave Lutz is the executive director of Neighborhood Open Space Coalition, which works for a healthier, greener city.

Back to the Sustainability Watch homepage

Â