Storm Warnings

Until the middle of the 20th century, such monsters weren't given names. They were simply called hurricanes. This particular hurricane was no simple one. At its peak, it had winds in excess of 160 miles per hour. It spit out storm surges from 10 to 12 feet. It whirled and raged up the Atlantic seaboard until it made landfall on Long Island on Sept. 21, 1938.

Once on land, it tore out a piece of Long Island, leaving a permanent hole, now called Shinnecock Inlet. It swept an entire movie theater, with 20 patrons inside, out to sea. It brushed aside whole farms, knocked out all electrical power above 59th Street and left the Bronx in total darkness. Before it was done, this storm, later to be called the Long Island Express, would take 700 lives, leave 63,000 people homeless and inflict $308 million ($6 billion in today's figures) worth of damage.

Could this happen again. And, if so, what can we do to protect lives and property?

Many experts say yes. "Roughly every 70 years the New York region gets a monster hurricane," Bill Evans, WABC-TV senior meteorologist and co-author of the new novel Category 7 wrote in an opinion piece in Newsday.

The National Hurricane Center's statistics corroborate Evans’ prediction. There seems to be a 20-year pattern in the frequency and intensity of Atlantic coast storms and hurricanes. Based on this pattern, the New York area can expect one or more category 3 Atlantic coast storms in the next several years.

|

Be Prepared The Office of Emergency Management has sent out over a million brochures, entitled Ready New York (Hurricanes and New York City), that give advice on what to do if a hurricane strikes and also designates where the evacuation zones are. As a first step, the office’s press secretary, Andrew Troisi, recommends that you go to the Office of Emergency Management's web site or call 311 to find the location of your local evacuation center. The office also recommends that New Yorkers: --develop a plan designating a place where the family should meet in case of an emergency; --create an emergency kit with 1 gallon of drinking water per person, canned food and a manual can opener, first aid kit, flashlight, radio (preferably the wind up kind that doesn't need batteries), 1 quart of bleach and an eyedropper for disinfecting water, phone, whistle and personal hygiene items; --put together a "go" bag in a waterproof package with things you may want to take with you in a waterproof package such as ATM and credit cards, $50 to $100 in cash, copies of important documents, car and house keys and current medical information, including doctors’ numbers.

|

|

Such a storm, Evans writes, "could send a 22-foot surge of water into Manhattan streets. Subways would be out for months …. Low-lying neighborhoods south of Sunrise Highway would be unrecognizable."

The city has not ignored this danger. Faced with the possibility of a severe hurricane or other storm, New York City’s Office of Emergency Management has developed a comprehensive storm plan for the city. It has assembled emergency plans, designated evacuation routes and advised New Yorkers on how to prepare (see box). But critics say the plan does not do enough.

Certainly New York presents some particular challenges to emergency planners. These include:

-- Many routes out of the city, jammed even on a normal rush hour, could become totally impassable in the event on an evacuation.

-- Millions of New Yorkers do not have cars they could use to evacuate the city.

-- The city is home to a large number of nursing homes and hospitals with sick and elderly people who could be difficult to move in an emergency.

-- New York’s aging infrastructure has proved vulnerable even to relatively minor downpours and storms.

Has the city done enough to address these concerns, particularly in low-lying areas such as the Rockaways? What more needs to be done?

Dangerous Storms

A hurricane is an organized rotating weather system that develops in the tropics and has a warm center of low barometric pressure with sustained winds of 74 miles per hour.

The strength of all hurricanes in the Western Hemisphere is measured by the Saffir-Simpson scale, which classifies storms into categories 1 to 5 based upon their wind speed and the height of the storm surge -- the coastal water blown inland.

A category 1 storm has sustained winds of 74 to 95 miles per hour and a storm surge of 4 to 5 feet. A category 5 hurricane has sustained winds of at least 156 miles per hour and a storm surge of 19 feet or more.

The New York-Long Island area has been hit by four category 3 hurricanes, with the most recent onestriking Long Island in 1960.

But hurricanes aren't the only potential threats out there. A Nor’easter, named because it generally travels northeast up the Atlantic seaboard, is not as organized or as windy as the hurricane but because it hangs around longer, can be just as destructive. A Nor’easter is formed when the cold dry arctic air of the jet stream blows south and collides with the warm moist air of the Gulf of Mexico. The resulting quarrel gives birth to an icy storm. Nor’easter winds are not as intense as those from hurricans, but because the storm has no eye and is irregularly shaped, a Nor’easter can cover a greater distance and therefore inflict as much damage as a hurricane.The City’s Plan

To cope with severe storms, the Office of Emergency Management has divided the city into three different kinds of zones -- A, B and C – ranked according to their likelihood of being flooded, according to the office’s press secretary, Andrew Troisi.

Zone A areas are low-lying lands likely to flood if any hurricane strikes the city. These are located in lower Manhattan, Coney Island and Brighton Beach, parts of the Rockaways, southern Queens and large sections of the coasts of Staten Island.

Zone B areas are less vulnerable low-lying lands where there will be flooding if a severe hurricane – category 3 or higher -- strikes the city. Zone B areas include Roosevelt Island, City Island and much of southern Queens, including John F. Kennedy International Airport.

In Zone C areas, flooding would occur only if a category 4 or 5 hurricane strikes the city. Among these areas are parts of East Harlem, and much of the eastern Bronx.

Most areas of the city, neighborhoods in the middle of Brooklyn and Queens, for example, as well as much of Manhattan’s West Side, are considered to be safe from a storm surge, regardless of the intensity of any hurricane. The city has not designated any evacuation center for New Yorkers in these sections.

Although New York is surrounded by water – and located on three different islands – unlike New Orleans, most of the city does not lie below sea level. "We can keep New Yorkers safe as long as we can get those affected to shelter," Troisi says. Currently, the city could provide shelter for more than 600,000 people.

In general, the city has tried to encourage New Yorkers to prepare themselves for a hurricane or other disaster (see box). "The key to any plan begins with education. First, find out if you live in an evacuation zone, then find out where your local evacuation center is," Troisi said.

To help residents find their evacuation center, the city has an on-line Hurricane Evacuation Zone Finder.

Subways, Cars and Buses

Since so many New Yorkers do not own cars, the city would use public transportation and extra buses to evacuate as many as 2 million people.

But simply having a vehicle might not be enough, Evans said in an interview. In a hurricane or other emergency, he said, "It's a matter of evacuating 2 million frightened people by public officials who have no experience in dealing with a crisis of this proportion. It's a matter of convincing people that this is something that they have never faced before…. People must realize that flooding is different from snow. We can shovel away many feet of snow; you can't shovel the ocean."

New Yorkers who normally rely on the subway system might find it shut down during a severe storm. Severe downpours and, in some places, high winds, shut down much of the subway system on August 8. Last week, the Metropolitan Transportation Authority issued a report concluding it had been unprepared for the storm and mishandled many aspects of the situation, particularly communicating to its own staff and to riders about the service disruptions. The authority committed itself to a number of steps, from giving Blackberry-like devices to its employees to installing new valves on drainpipes, to help prevent similar problems in the future. But despite such measures, authority executive director Eliot Sander said major storms would still have the potential to disrupt subway service in the future.

The Bronx River Parkway during the 2007 Nor'easter.

The sick and elderly could be particularly hard to evacuate. The office of Manhattan Borough President Scott Stringer reviewed 49 nursing homes last year and found that the state department of health had failed to adequately prepare them for evacuation.

" After the lessons learned from Katrina and the 9/11 attacks," Stringer said in a December 2006 press release, "it’s unacceptable, for New York not to have viable emergency plans for our most vulnerable residents."

For its part, the city has considered the problem of the sick and elderly and would be prepared to evacuate them, Troisi said. "Under our emergency evacuation plan we will move the sick and elderly to safety first," he said. Government agencies would have time to prepare because, Troisi noted, "a hurricane is the one natural disaster that we will have ample warning that it is approaching."

Consulting the Community

To improve the plans, many observers call for more involvement from community leaders and residents.

" Right now there's too much planning from on high, and not enough discussion with local officials," Mike Duvalle, a community leader in the Rockaways, said. City officials, he said, need to "work out a comprehensive plan with local officials -- and then you allow them to do what's needed, enact the plan, without having to go to back to city or state authority for permission."

Community Emergency Response Teams provide some role for individual neighborhoods in dealing with disasters. The teams receive training from the police and fire departments in basic emergency response. During the August tornado in Bayridge, for example, the local CERT responded and helped clean up, according to Laura Singara, press secretary to Brooklyn Borough President Marty Markowitz. The community teams in Sea Gate and Coney Island filled sandbags to prepare for a severe storm a few months ago.

The Vulnerable Rockaways

A major storm would not affect all parts of the city equally. Perhaps no area could prove as vulnerable as the Rockaways, a low-lying coastal peninsula with limited transportation.

Some 100,000 people live in Far Rockaway. The area, according to Duvalle, has the highest concentration of nursing homes and residential care facilities in New York. He estimates it could be home to as many as 3,000 sick and elderly people.

For the people in the Far Rockaway evacuation zone, the Cross Bay Bridge provides is only practical way out. The only other route is via the Nassau Expressway, a road running east from the Rockaways, which could be vulnerable to flooding. "We only have one subway out of the area, and that line is an elevated one and therefore it is exposed to the full brunt of a hurricane," Duvalle said. "We can't depend on evacuation alone."

John Baxter, cable talk show host and Far Rockaway community leader, laughs when asked whether the city is prepared to evacuate 3,000 people from Rockaway. "Get down on your knees, and say a prayer, and while you're down there kiss your butt goodbye," he said. "There is absolutely no way you can evacuate all these people."

To try to provide additional ways out, Queens Borough President Helen Marshall obtained money to buy Jet Skies for water rescues and inflatable water rescue rafts for the fire department. She now wants funds to purchase ferries that could be used to help evacuate Far Rockaway, press secretary Dan Andrews said.

" We must use all our resources," Duvalle said. "We can have private yachts listed for the purpose of evacuation. We should provide generators for gas stations in case of power outages - their tanks need electricity in order to pump. Our cars need their pumps in order to evacuate."

In addition Marshall believes steps must be taken to prevent disastrous flooding before it occurs. "Part of the reason why in the past southeast Queens has suffered through chronic flooding, is because the growth and development of the infrastructure has never kept pace with the growth and development of the area's population," Andrews said.

Flooding in the Rockaways

Evacuation would not be the only problem, according to City Councilmember James Sanders, whose district includes Far Rockaway and flood-prone southeastern Queens neighborhoods. He is concerned about Belmont Park racetrack, where many of his constituents could be taken in the event of a disaster. According to Sanders, "Some experts have noted that Belmont itself is on low-lying ground and in the event of a Katrina-like storm may be prone to flooding."

Sanders thinks the city should consider an alternative approach called sheltering in place. "The idea is when evacuation is neither possible or practical you make use of resources at your disposal and shelter in place," Sanders said. In Far Rockaway, where there are many tall apartment buildings, it could make sense to set up evacuation centers on upper floors of those buildings.

Jonathan Gaska of Far Rockaway’s Community Board 14 has doubts about this idea. Without backup generators, he said, these buildings could be without electricity, knocking out elevator service.

In general, Sanders faults the city’s planning for his district. "As a former marine I understand a little something about survival," he said. "Survival is a mindset that comes from preparation and creative thinking. The OEM's present mindset of evacuation alone doesn't have enough in regard to the former and nothing in regard to the later. My worse nightmare is for my district, in the wake of a Katrina-like storm, to end up being New York's Ninth Ward."

Not everyone in the Rockaways is critical of the city. Gaska said Katrina was "a slap in the face" that changed the attitude at the Office of Emergency Management. Since then, he said, "The OEM has been very good working with us." While the office has not agreed to all the community board’s requests, it has posted evacuation route signs along the peninsula and put backup generators in firehouses.

A Growing Threat?

Some meteorologists fear that New York could face an increased number of severe hurricanes in the future. They point out that, while the frequency of hurricanes has remained the same, the intensity of the storms has increased. Some say global warming could be causing this, although other scientists consider such arguments alarmist.

The experts disagree on whether global warming contributed to the devastation caused by Hurricane Katrina, but some believe that if the ambient water temperature of the Atlantic Ocean goes up by one degree Celsius the higher water temperatures could create monster hurricanes. In light of this, could a category 5 hurricane strike New York?

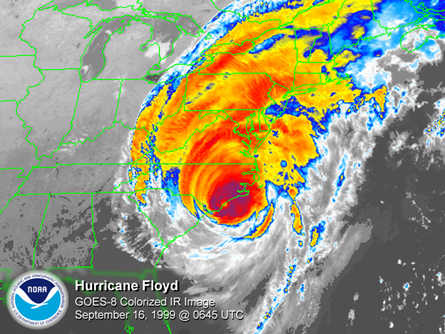

Officials feared Hurriance Floyd might hit New York City in 1999 but its effects on the city were minimal.

Troisi says no. "The temperatures of the waters surrounding the city are simply too low to allow for the development of any hurricane above the magnitude of a category 3," he said.

But a trip to the Rockaways leaves no doubt that even a category 3 storm could pose a major challenge. Duvalle drives over the Crossbay Bridge where vast expanses of water are all one can see on either side. "Imagine this highway filled panicky drivers in the middle of hurricane weather," Duvalle said.

On Rockaway beach scores of newly constructed condos are going up. A short distance beyond the condos is a narrow beach, beyond that nothing but a vast expanse of ocean and sky. Along the sea's horizon, misty white clouds are swept along by a steady wind. Speaking over the wind, Duvalle anticipates a future storm. "It is coming," he said. "It is not matter of if it comes - it is matter of when."

Thurman William Mathis is a schoolteacher who writes for the Queens newspaper "Our Times."Â

How Clean (or Dirty) Is Our Air?

During the spring, buried in the thickets of the debate over congestion pricing, was a great nugget in Mayor Michael Bloomberg’s PlaNYC 2030. Deep in the document was a promise: if PlaNYC 2030 was implemented, New York City would become the “cleanest big city in America.”

That got me thinking.

How clean is the air in New York City?

The short answer is that the nation’s air is cleaner than it’s been in decades, and so is New York’s. But New York City air is still polluted enough to send thousands of people to emergency rooms every summer and to send some of those people to early graves every year.

The longer answer is more complicated, and it goes like this:

Since 1970, the U.S. Environmental Protection Agencyhas set standards for the maximum amount of air pollution that is safe to breathe. In a city like New York, ozone (a principal ingredient of smog) and particulate matter (or soot) are the key pollutants—and the city has never met EPA’s standards for either pollutant. In each case, we are in the second-worst category (Los Angeles tops the "most polluted list" for both smog and soot). By this measure, the city seems to be in pretty bad pollution shape—especially because many environmental groups think that the current EPA standards are too weak.

Soot particles are the biggest pollution concern. A decade ago, the Natural Resources Defense Council (where I worked then, and now) estimated that 64,000 Americans died prematurely every year at then-current levels of particulate air pollution. More than 4,000 people of those premature deaths were in the New York metropolitan region.

In New York, diesel engines have long been at the heart of our local soot problem. When walking up Madison Avenue, most of the soot we breathe comes from a relatively small number of diesel engines—buses, trucks, and construction equipment. In more residential neighborhoods, home heating oil is diesel’s close—and even dirtier—cousin.

Sources of Particulate Soot on Madison Avenue

Diesel (and home heating oil) soot is really toxic stuff. If it’s not effectively filtered in the tailpipe, typical diesel exhaust contains dozens of cancer-causing chemicals. This toxic soup has been found to be at least a probable or likely human carcinogen by many of the world’s leading public health agencies, including the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency, the National Toxicology Program and regulators in Germany, California and elsewhere.

Luckily, diesel soot pollution is a fixable problem. As of this year, all new diesel truck and bus engines are equipped with filters that remove more than 90 percent of this soot. And, NYC Transit buses have used these filters effectively for several years now, reducing their fleet-wide emissions by more than 95 percent since 1995. But most trucks, buses, and construction equipment don't have these filters.

So, in 2005, the Boston-based Clean Air Task Force revisited the soot problem, and focused on the specific problem of diesel soot. The task force estimated that people in Manhattan inhale enough toxic soot particles to create a lifetime cancer risk that is more than 3,200 times EPA’s so-called “acceptable” cancer risk. It gets even worse: According to the task force, more than 40,000 asthma attacks and almost 1,800 premature deaths were attributable to diesel soot pollution in neighborhoods throughout the city in 1999. That’s why the American Lung Association recently gave the City an “F” for its particulate soot levels.

But is the air really so horrible? As I write, the sky outside my window is bright blue. My daily “EnviroFlash” email from EPA and the New York State Department of Environmental Conservation tells me that today’s pollution levels are “good” for both particles and ozone.

OK, I know better: EPA and environmental conservation department give a regional estimate. That estimate tells me nothing about local conditions. Recent studies show that diesel soot emissions along roadways create corridors of increased pollution, which leads to higher health impacts. Perhaps the most famous example can be found in northern Manhattan: With five Metropolitan Transit Authority bus depots and several busy north-south truck routes, Harlem and Washington Heights have higher air pollution levels—and much higher asthma rates—than their southern neighborhoods.

All of this underscores two important themes. First, it is important to acknowledge that we’ve made significant progress in reducing many sources of air pollution over the years, and our air is cleaner as a result. But, second, it is equally important to understand the job isn’t finished—we still fail to meet EPA’s health standards for ozone and particulate soot, and we need to create new ways to address the remaining sources of air pollution that seem to be pocketed in certain areas of the city.

Mayor Bloomberg’s PlaNYC 2030 strives to ensure that “every New Yorker” should breathe the cleanest air of any big city in America. We’re not there yet. Next month, I’ll dive into the plan and explore whether the plan will us meet his goal.

Rich Kassel is a senior attorney at the Natural Resources Defense Council (NRDC), where he focuses on urban air pollution and transportation issues. He also chairs the Tri-State Transportation Campaign, a regional transportation advocacy organization, and is on the boards of the New York League of Conservation Voters and Transportation Alternatives.

Â

Making Coney Island Green

The city took a step toward sustaining historic Coney Island this summer when it put a roadblock in front of a $1.5 billion plan by Thor Equities to turn the legendary area into a resort enclave. As New Yorkers warmed up on Coney’s beaches, the administration threw cold water on the proposal to speed up the rides and bring in hotels and time-shares. Thor’s scaled-back plan, which included a glass-enclosed water park, three hotels and 400 time-share units, restaurants, movie theatres and high-tech arcades, was a bit much even for a city administration that likes to think big.

Now the question is whether the city can come up with an alternative that helps to sustain and build up what is left of the storied amusement area. Will they be able to do it without a mega-developer like Thor? And will the city continue to react to the schemes put forth by private developers rather than coming up with ideas of its own?

As incongruous as it might seem, Coney Island, with its honky-tonk image, could become a model of sustainable development. If the city wants that to happen, it could look to some key decisions already made at Coney.

Where’s the Plan?

New York City’s long-range sustainability plan, PlaNYC2030, says little about unique areas like Coney Island, which don’t fit in the category of residential neighborhood or an average business district. However, Coney Island redevelopment could play an important role in meeting the plan’s objectives of insuring that all New Yorkers live within a 10-minute walk of open space, cleaning up the city’s waterways, improving mass transit and air quality and reducing global warning.

If the past is any indication, the way to accomplish these objectives is through carefully thought-out small steps over a long period of time instead of giant commercial adventures and “big ideas.” For example, long before PlaNYC2030, the Metropolitan Transportation Authority renovated the Stillwell Avenue subway station, making it the greenest, most energy-efficient subway station in the city. Completed in 2006, the station has photovoltaic panels that provide solar energy and an open design that maximizes the use of natural sunlight. This example of smart design and public policy has given a small boost to the private amusement area and to many public facilities in the area.

Previously, the city preserved the Cyclone, Coney Island’s famed roller coaster that opened in 1927. It became a city landmark in 1988 and a federal landmark in 1991. This mostly wooden structure remains an icon of the amusement area, marking its identity as distinct from the kind of high-tech, high-priced theme parks epitomized by Six Flags.

The corporate amusement giants also cannot replicate the non-profit, Coney Island USA a focal point for many unique cultural and civic groups that have helped keep the historic area alive. And in yet another small step, the city government and the Coney Island Development Corporationnow plan to develop Steeplechase Plaza, a public park that would feature a restored B&B Carousel.

So it may be smarter for the city to think smaller and move one step at a time. The popularity of the relatively tiny Nellie Bly Amusement Park, only a couple of miles from Coney Island near Bensonhurst’s waterfront, suggests that many small parks might work better than one big one.

Stadiums On The Island?

In an earlier effort to spark development at Coney Island, the city encouraged the building of Keyspan Park, where the Brooklyn Cyclones minor league baseball team plays. This was a questionable addition to Coney Island’s waterfront when it was built during the Giuliani administration. The minor league field broke the classical Coney Island model that combined amusement park, beach and boardwalk. Stadiums for professional teams and leagues are great for team owners and the health and welfare of the small number of athletes who play in the stadiums, but do little more than encourage the sedentary lifestyle and junk food binging that contribute to the city’s epidemics of obesity and diabetes.

Still, compared to the monster Shea and Yankee Stadiums, Keyspan Park has opened the door to a different kind of professional sports. Much smaller than the baseball behemoths, Keyspan is only a stone’s throw from the boardwalk and beach, and the Abe Stark skating rink, and within walking distance of the amusement park. With affordable ticket prices and easy access via mass transit, it attracts families with limited recreational options in their neighborhoods and works as part of a daily outing. On the other hand, Shea and Yankee Stadiums function as enclosed enclaves, attracting a large fan base that drives, and they funnel people in and out as quickly as possible.

And why not put the arena for the Nets basketball team in Coney Island, as planner Simon Bertrang proposes? Two previous studies recommended Coney Island as a location for a professional arena, and until recently that view was held by Brooklyn’s political establishment. Wouldn’t the 18,000 seat arena that the basketball team’s owner, Forest City Ratner, now proposes to cram in between the Prospect Heights and Fort Greene neighborhoods make more sense nested in Coney Island’s amusement area?

If this was to happen – which is admittedly unlikely -- a Coney Island arena should not go the way of the New York Aquarium, which is isolated from the amusement park. Nor should it be dropped in next to Keyspan Park, thereby creating a big enclave of professional facilities. But if properly designed, the home court for the Nets could be physically integrated with Coney Island’s recreational facilities.

The City’s Role

The heart of Coney’s surviving amusement area, Astroland Amusement Park, closed for the season on September 9. The owner of the land, Thor Equities, may very well decide not to renew Astroland’s lease for next year’s season, although a petition campaign is underway to prevent this from happening.

Lacking the kind of public or private commitment given to the Cyclone and B&B Carousel, no amusement park can survive and keep prices affordable to average New Yorkers. Thor wants public subsidies to support any amusements it puts on the site.

In light of this, it is hard to imagine any steps at Coney Island going forward until the administration takes a more direct role in development. In the past, however, the city has tended to rely more on rezoning than direct intervention. Zoning leaves the door open for development but can’t substitute for complex planning with a strong dose of preservation, community engagement and attention to detail.

For a number of reasons, Coney Island cries out for an active city role. If we look to the year 2030 and beyond, Coney Island will probably be one of the most vulnerable areas to rising sea levels. While Coney’s 60,000 residents may be willing to risk flooding and evacuation, it certainly makes no sense to encourage more permanent housing there. Millions of dollars in public subsidies already go to maintain Coney Island’s beach and protect it from erosion. When will the cost of such efforts exceed the public benefit?

Beyond this, a strong public role is imperative if Coney Island is to remain affordable to New Yorkers, both as a place to live and a place to play. Today the park and recreation areas are a boon for New Yorkers with limited incomes and for Brooklynites. Preserving affordability on what was once known as America’s playground is as important as saving the Cyclone and is consistent with PlaNYC2030’s aim of preserving affordable housing.

See: Coney Island’s Summer of Reckoning and With Pizza, Pinball and Panache, Boardwalk Vendors Face Changes

Â