Name that Street

|

Hundreds turned out to celebrate last July as a portion of Church |

Update: On May 30, a sharply split City Council defeated an amendment that would have had the effect of renaming part of a Brooklyn street for Sonny Carson. For more, click here.

Millions of people in New York City walk, jog and stumble across streets named for the famous and the not so famous. New Yorkers can explore Columbus Avenue, jam on Bob Marley Boulevard, or be cool on Humphrey Bogart Place, but they can also stand and snicker at the corner of Seaman (named for a 17th-century landowning family) and Cumming (so dubbed in 1925 in honor of a now obscure local property owner).

Whether honoring celebrities or obscurities, street namings are generally quiet affairs with the City Council essentially rubber stamping the recommendations of the community boards. But the dispute over a four-block section of an avenue in Bedford-Stuyvesant Brooklyn has renewed focus on the naming and renaming of city streets. On Wednesday, City Council will vote on a bill to rename 51 city streets in honor of various personages. The bill is controversial because of a name that is not in it - that of the late black activist Sonny Carson, hailed as a community hero by some and condemned as a bigot and criminal by others. A sharply divided council committee voted to delete Carson from the package last month. This debate follows another naming controversy - that one involving Corbin Place in Brooklyn, which got its name from Austin Corbin, a longtime Brooklyn developer and an anti Semite.

The council's predilection for devoting energy to street names most people will never use (Avenue of the Americas, for one) is often mocked as a waste of time, but in taking such action the council and by extension, the city has the power not only to bestow honors but also rewrite history. This raises the question of who gets to tell that history and determine who is a local hero - or a local villain. "Street names function as a barometer of social values at a given time, and as such have historical significance that goes beyond a name," wrote Leonard Benardo and Jennifer Weiss, authors of Brooklyn by Name: How the Neighborhoods, Streets, Parks, Bridges and More Got Their Names.

THE POWER TO NAME

|

From Corbin, the anti-Semite, to Corbin, the Revolutionary War hero? |

As the City Council seeks to establish itself as a serious legislative body, its penchant for renaming streets has become an easy target. In the wake of the September 11, 2001 attack on the World Trade Center, Councilmember James Oddo of Staten Island said the ceremonial gesture was a "luxury the city can no longer afford." Turning away from that task, he wrote at the time, "would symbolize a tangible step in redefining our role." In 2002, Oddo proposed a bill to take the council "out of the name changing game" by leaving the approval of the street renamings to community boards and allowing the council to override any ones it objects to.

The council did not go that far but rather than vote on all the name changes individually, since 2002,it has voted on street naming proposals in two package bills a year.

At the same time, the number of name changes has increased. In 1986, the parks committee evaluated just 25 proposals over the entire year. After 9/11 the number of street names began rising as the council started honoring rescue personnel and others who died in the attack. Last spring, for example, the City Council renamed 58 streets in the city, many for people who died in the terrorist attacks.

HOW IT'S DONE

|

|

Proposals for street renamings begin at the neighborhood level when local residents recommend a street name, usually in honor of a deceased neighborhood figure, to the local community board. Sometime they circulate petitions to demonstrate support.

The community board then approves or rejects the plan. Some community boards are reluctant to rename streets. When "Jerry Orbach Way" failed to pass Manhattan Community Board 5, Orbach's widow Elaine brought the proposal to neighboring Community Board 4, which approved the recommendation to rename the other corner of 53rd Street and 8th Avenue after the actor. Some community boards like to dole out the honors, as chairman of Manhattan Community Board 6's transportation committee Lou Seperky has noted: "There used to be a habit that we'd just name something after anyone who sneezed." Community Board 6 will likely recommend Kurt Vonnegut Way for the next package of street name bills.

Whether a struggle or a sneeze, if a community board votes to pass a street renaming proposal, the local council member then brings the recommendation to the Parks and Recreation Committee. If the committee affirms the proposal, the renaming is submitted to the council for a vote in one of the package bills. When and if the council votes yes, a new sign with the honorary name is erected next to the marker with the current, more mundane, label. (The original street names remain on all street maps.) So, for example, a new sign for Vonnegut Way would be added to the existing post overlooking the corner of 48th Street and Second Avenue where the writer used to walk his dog Flour.

THE CARSON CONTROVERSY

While Vonnegut has his detractors, a corner with his name is unlikely to spark the kind of furor that has surrounded the proposal for Sonny Carson Avenue. Since its introduction, the four-block stretch has been a constant topic of council meeting discussion, divided council members and prompted a lawsuit. And it has spurred Oddo to consider reintroducing his 2002 street renaming bill

Sometimes referred to as "The Mayor of Bed-Stuy," Sonny Abubadika Carson, a Korean War veteran, was involved in a variety of local causes in the local black community, such as the Republic of New Afrika, the African Burial Ground project, securing voting rights for ex-prisoners, the Black Men's Movement Against Crack and protests against police brutality. Additionally, his autobiography was turned into a movie The Education of Sonny Carson.

Recommended by the local community board and submitted for consideration by Councilmember Albert Vann, Carson would seem to be shoo in for an honorary street name. But Carson also had a record of criminal and racially motivated activities. In 1974, he served time in prison for kidnapping. He organized boycotts of Korean groceries where the protestors held up signs saying, "Don't Buy From Koreans" and "Don't Shop With People Who Don't Look Like Us." Carson said at the time, "In the future, there'll be funerals, not boycotts."

The activist made little secret of his attitudes. When asked about his anti-Semitic statements, for example, Carson replied, "I'm anti-white. Don't just limit me to a little group of people." And in a 1987 interview with the New York Times, Carson said, "You don't give us any justice, then there ain't going to be no peace. We're going to use whatever means necessary to make sure that everyone is disrupted in their normal life."

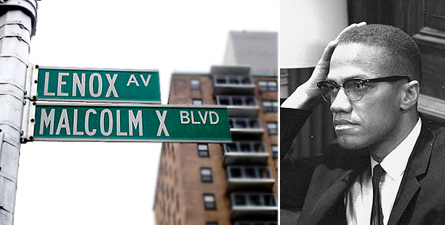

A stretch of Sixth Avenue north of 110th Street was renamed Lenox Avenue in 1887 after millionaire philanthropist and book collector James Lenox. In the late 1980s, the street got another name change to recognize Malcolm X.

But those backing the renaming say it is up to people in the community, in this case Bedford-Stuyvesant, to determine who they can honor. Explaining Carson's significance, Vann said, "He came into prominence at a time when the black community was asserting itself, defining itself, claiming itself and trying to make the community better for black people - he was a part of that struggle."

When it came time for the parks committee to vote, it split along racial lines with three white members -- Alan Gerson, Joseph Addabbo and Dennis Gallagher - voting to delete Carson's name. Chairwoman Helen Foster, who is black, voted against its removal, and another black member, Letitia James, abstained.

At a council meeting following that vote, Councilmember Charles Barron criticized the council for voting to "block the black community from self-determination of selecting our own heroes." He asked, "What could be more divisive, whether intentional or unintentional, than have four white members of this city council tell an entire black community no?"

Vann, who like Barron is black, also voiced concerns about the council setting a precedent for overriding local interests. "We can vote as a council against my district and against my community and against our self-determination," he said. Vann apparently takes a fairly broad view of that right. During a television appearance on NY1, he responded to a hypothetical inquiry about a German community wanting to name a street after Adolph Hitler. "I don't think they could withstand the pressure of doing that, ok? Do they have the right to offer that up? Yes, they do," Vann said. "If you could live with that identification, then I don't have a problem with the process."

Two members of the local Brooklyn community board sued the city council for removing Carson's name from consideration. Presiding Judge Leland DeGrasse rejected the claim, ruling that because the renaming of streets is a legislative matter rightfully under the purview of the city council.

AND WHAT ABOUT ALL THOSE OTHER STREETS?

During the heated debate, Barron said that, if the council failed to honor Carson, he would demand information on every person recommended for an honorary street name in the future. "We got street names of slave holders and racists all over Brooklyn," Barron reportedly said. Whether or not the council agrees with Barron's other comments, the frequency of streets named for slaveholders is indisputable.

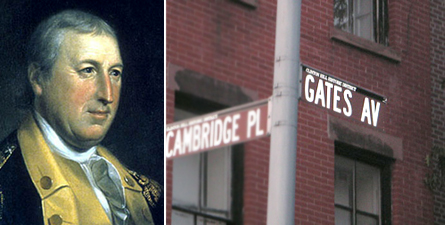

By one count, at least 70 New York City streets has slave owner names Takes Gates Avenue, the very name once slated to bear Carson's moniker. Its name honors Horatio Gates, a Revolutionary War general. For part of his adult life, Gates owned a Virginia plantation and slaves, although he freed them in 1790.

An influential historical figure and "founding father" of America, Thomas Jefferson is honored with a park and a high school (ironically in Barron's largely black). But as Barron pointed out at a recent council meeting, Jefferson could also be described as a slaveowner, rapist and pedophile. Foster added that Jefferson sold his own children into slavery.

Horatio Gates, a Revolutionary War general, whose name now graces what some would dub Sonny Carson Avenue, owned slaves who he eventually freed.

Of course, not only slaveowners are controversial. In 2003, the city renamed the corner of the Bowery and 2nd Street as "Joey Ramone Place," in memory of the Ramones singer. He got this honor despite having spent a number of years with a fairly major cocaine habit

The New York City Council has recognized the socialist and anti-imperialist activist and poet Pedro Pietri by renaming East Third Street between Avenues B and C in his honor. The council was apparently not alarmed that Pietri founded the Young Lords Party, which in the 1970s was often likened to the Black Panther Party

And Barron has criticized the council's accolades for the entertainer Al Jolson, who performed in blackface. New School Professor Joseph Ciolino, who has studied Jolson, has said the entertainer stood up for equality both on and off Broadway, and wore blackface for cosmetic effect. True or not, many New Yorkers still might not be amused.

And then there was the Bernard Kerik Correctional Center. In December 2001, while Kerik, a former city corrections commissioner, still served as police commission, Mayor Rudolph Giuliani agreed to rename the Manhattan House of Detention, popularly known as the Tombs, in Kerik's honor. Less than five years later, after Kerik had pleaded guilty to misdemeanor charges, had been accused of seamy --if not illegal conduct -- and was still the subject of sundry other investigations, Mayor Michael Bloomberg removed his name from the jail.

The names of anti-Semites grace several street signs as well. Take Corbin Place, for example. Austin Corbin, a onetime president of the Long Island Rail Road, was also a member of the American Society for the Suppression of Jews who once asked, "If this is a free country, why can't we be free of the Jews?" Today, a thriving Jewish community resides on the street named after him, which some rabbis consider to be the best revenge. Others disagree and want the city to rededicate the street to another famous Corbin: Margaret Corbin, a Revolutionary War heroine. This way, the council can revise history without forcing residents to change their addresses.

But another anti-Semite is likely to keep his streets. New Amsterdam Governor Peter Stuyvesant, who tried to get the first Jewish settlers in America, expelled has his name attached to a large avenue, an apartment complex, a post office, a high school and other New York fixtures.

STREETS THAT FAILED

If Carson does not get his street, he will have company. A 1986 proposal to rename a street in honor of Ben Gurion, the first president of Israel, failed when representatives of the American-Arab Relations Committee and the American-Arab Anti-Discrimination Committee testified against the recommendation, citing considerations for Palestine's independence and safety.

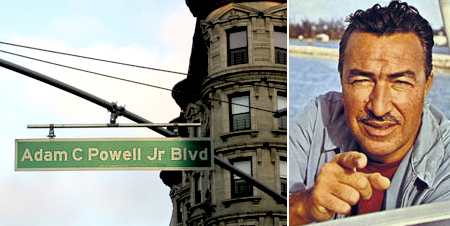

During his life, U.S. Representative Adam Clayton Powell attracted controversy but there was little opposition to putting his name on a portion of Seventh Avenue in his old congressional district.

Councilmember David Weprin withdrew a proposal to rename a street after assassinated Israeli tourism minister Rehavam Zeevi when he learned of Zeevi's hatred of Palestinians

City Council Speaker Christine Quinn has rejected efforts by activists to rename a Harlem street for Mumia Abu-Jamal, who has been on death row in Pennsylvania since being convicted of murdering a police officer in 1981. "Commemorative street renamings are generally awarded only posthumously. To the best of my knowledge, Mumia Abu Jamal is still alive, and is therefore not eligible to have a street renamed after him," she reportedly wrote one advocate.

Not bound by such considerations, in 2006, the Paris suburb of St. Denis France named one of its streets for Abu-Jamal. The U.S. Congress then passed a resolution asking the French government to remove the sign, thereby proving members of the New York City Council are not the only Americans to make a big deal of street names.

Â

Debating a Greener Future

Mayor Michael Bloomberg's plan for a larger but more environmentally friendly New York City continues to attract praise and criticism. And already the plan is makings its mark.

In the days since the Earth Day speech, Bloomberg announced an executive budget that took some very early steps toward financing his grand vision. (See related story.) He revealed a plan for a largely industrial area near Shea Stadium, which he said exemplified green principle. Others disagreed. (See related story.) And the building department announced a long awaited revision of the building code that, among other things, would encourage environmental sound construction.

This week we offer more commentary and analysis of Bloomberg's vision to create an environmentally sustainable city heading toward the middle of the 21st century. Last week, our Sustainability Watch focused on the plan as a whole, but this week we look at specific parts of the proposal -- from its plans to clean up contaminated areas to how the bills will be paid. (For a guide to articles by topic area -- transportation, energy, land and water, money and jobs -- see below.)

Sustainability Watch, a joint project of Gotham Gazette and the Hunter College Center for Community Planning & Development, will try to keep alive the debates about what's good and not, look at what's missing, discuss how the plan is working and monitor the gaps between plan and practice. As part of this, we continue to urge you to comment on these articles and the mayor's plan through our message boards (attached to every article) or by emailing us at info at GothamGazette.com.

Transportation

The Outlook for Congestion Pricing

The Outlook for Congestion Pricing

By Bruce Schaller

Schaller Consulting

Officials from the outer boroughs and the suburbs have rushed to condemn the fee, but as the debate continues, the political calculations could change.

A Fee to Level the Playing Field

By Brian Ketcham

Traffic engineer

Motorists cost the rest of us billions of dollars a year. Congestion pricing aims to correct that.

Paying to Drive and to Park

By Paul Steely White

Executive director, Transportation Alternatives

Faced with likely opposition to his laudable plans for congestion pricing, Mayor Michael Bloomberg should also try to raise the cost of parking.

Improve Transit, Then Charge to Drive

By Hope Cohen

Deputy director, Center for Rethinking Development

Political and technological issues could stall congestion pricing, but there are many transit improvements the mayor can make in the meantime.

Reaping Real Benefits from Congestion Pricing

Carolyn Konheim

Chair, Community Consulting Services

Along with charging fees to motorists, the city has a number of other tools available to reduce traffic on our roads -- and some of them could be instituted quickly.

Energy

A Start on A Cleaner, More Efficient Future

A Start on A Cleaner, More Efficient Future

John Nettleton

Cornell Cooperative Extension

If New Yorkers are really going to use less energy and cleaner energy, more must be done to educate the public and promote alternative sources of energy.

Finishing the Job

By Mike Gordon

President and founder, ConsumerPowerline

The mayor has taken a good start on the road to a sustainable energy future, but tough choices lie ahead, including whether to have electricity cost more.

Land And Water

What plaNYC Does Not Do

What plaNYC Does Not Do

By Dave Lutz

Executive director, Neighborhood Open Space Coalition

Any plan for a bigger, more environmentally friendly city needs to include more parkland and encourage community gardening.

Greening New York's Brownfields

By Mathy Stanislaus and Jody Kass

Co-directors of New Partners for Community Revitalization

The plan to clean up and develop contaminated areas could provide needed land and eliminate health hazards -- if it's done right.

Willets Point Plan -- Green or Grandiose?

Tom Angotti

Director, Hunter College Center for Community Planning & Development

The mayor's plan for Willets Point, the Iron Triangle of Queens, raises question about the city's vision of sustainable development.

Sustaining Neighborhoods

Sustaining Neighborhoods

By Phil DePaolo

President, New York Community Council

While the mayor sees Williamsburg-Greenpoint as a model for development elsewhere in the city, the rezoning there has changed the character of the area and forced out many long-time residents.

A Plan for Misplaced Development

By Marcy Benstock

Director, Clean Air Campaign

City Hall's proposal could foster development in waterways and floodplains --increasing the risks of storm and flood damage and endangering habitat.

Money and Jobs

Reality Check

By Carter Craft

Director of programming and operations, Metropolitan Waterfront Alliance

Director of programming and operations, Metropolitan Waterfront Alliance

In a city where grand visions often falter, Mayor Bloomberg confronted budget issues head-on, helping his plaNYC pass the "do-ability test."

Paying for plaNYC

By Glenn Pasanen

Professor, Lehman College

There's little evidence of the mayor's big plans in his latest budget, but he hopes the state will create a new authority to fund his 2030 programs.

Spreading the Benefits

By Annette Bernhardt, deputy director of the Justice Project at the Brennan Center for Justice, and Adrianne Shropshire, executive director of New York Jobs with Justice

The mayor's vision must include a focus on good jobs with decent wages if growth is to benefit all New Yorkers.

Â

On Energy, Consider the Alternatives

My high school's motto, "finis origine pendet" can be translated as "well begun is half done.'" On energy, Mayor Michael Bloomberg's plaNYC is a well-begun start, with the well-intentioned design of a new Energy Efficiency Authority within a new Energy Planning Board. Such an overarching governmental framework is vital to reducing New York's "'carbon footprint' - the sum of all the greenhouse gases we emit. But community-grounded measures and daily practices must compliment such an effort given the fractious nature of planning here.

Other initiatives could be expanded as well. The recommended measures to modernize power plants, improve the electrical grid and revise the building code revisions will help transform our environment. But an equally robust effort must focus on buildings: We have 100 "green buildings" in a city with 950,000 structures. Just as Bloomberg looked to his London counterpart for inspiration in traffic management, he can find innovative public programs in the U.S. for reducing our energy consumption.

Energy Education

Research has found that energy efficiency measures accompanied by education have a greater and more lasting impact than efficiency measures alone. Residents and owners maintain efficiency improvements to the extent that they understand their nature and effect. "An Energy Awareness and Training Campaign" should begin immediately in and the involvement of the Department of Education engagement is vital.

The city should also look at programs that provide energy efficient compact fluorescent lights to residents: Chicago's mayor is giving away 500,000 fixtures, which residents pick up along with basic energy information at their alderman's office. Commercial buildings, working with unions and the Apollo Alliance for Good Jobs and Clean Energy, must train maintenance staff so lights get turned off after 9:30 p.m.

Promoting Alternative Energy Sources

New solar generating capacity is critical to citywide peak load reduction, but the plan's conclusion that New York City is uniquely expensive overlooks the obvious. If installation costs here are 30 percent to 50 percent above those in New Jersey or Long Island, one should seek out areas within the five boroughs that mirror New Jersey and Long Island. Where are the largest expanses of publicly accessible land or south-facing surface area available for large-scale photovoltaic installations? One finds multiple options, from railyards (Sunnyside, Hunts Point) to roofs (airport hangers, for one) to public rights-of-way. In Denmark, highway shoulders and rail lines feature soundproofing berms mounted with photovoltaic panels. This could provide a model for large-scale solar-power generation along the many city highways, the Long Island Rail Road right-of-way and the entire above ground southern exposure of the Number 7 line.

Sacramento's municipal utility installs solar panels on private property on a leaseback arrangement and provides the panel-shaded parking (at a premium price) at the local airport. Developers could do something similar on the acres of rooftops in Hunts Point, Long Island City, along Atlantic Avenue in Brooklyn and elsewhere.

Fuels made from plant material - so-called biofuel -- offers a triple benefit: improving air quality and public health while reducing petroleum use and emissions of carbon dioxide and other pollutants. Fully half of New York City's houses and apartments -- nearly 3 million homes -- use oil-fired or dual fuel heat. This exposes owners and tenants to the vagaries of an increasingly volatile international oil market. Worse, it generates sulfur dioxide (23,500 tons in 2004) linked to New York's per capita death rate from so-called diesel fine particles - the third highest in the U.S., behind only Beaumont, Texas, and Baton Rouge.

The plan shortchanges biofuels in several ways. First, biodiesel can be blended with existing heating oil and burned in many existing furnaces. A fuel that is 20 percent bodies significantly reduces particulates, carbon dioxide and sulfur dioxide.

Three good first steps would demonstrate the potential of cleaner fuels. First, with the New York City Housing Authority heating over 80 percent of its 170,000 apartments with heavy oil, immediate conversion to heating fuel with 20 percent biofuel in developments located where asthma rates are particularly high is an environmental and a public health imperative. Using biodiesel for transit and school buses would benefit riders, drivers and residents, especially those in communities of color where bus depots are invariably sited. Third, complete boiler changeover in 100 NYC schools is largely unnecessary- many if not most can already use a blend of biodiesel and fuel oil.

As New York primes the pump for such renewable fuels it should not simply seek out the cheapest material. The growing of soya oil from Brazil and palm oil from Indonesia on clear cut land releases ten times as much carbon as petroleum production. PlaNYC can help pioneer a clearly needed green fuel certification modeled on current sustainable forestry.

Building Public Support

Citizens will respond to leadership and timely information. When the California energy crisis led officials to call for a 6 percent reduction in overall electrical demand, residents called for demand to be cut by twice that. A record of 'Best Practices' can excite and empower residents and building owners to take the next step. Couples waiting for marriage license at the municipal building could view material on saving energy. And at the end of the school year all 1 million public school students could depart for summer vacation, trained agents in reducing peak electrical demand.

John Nettleton is a senior extension associate at Cornell Cooperative Extension/NYC. In spring 1990, he designed and taught 'Urban Impacts of Global Warming' at Manhattan College, the first such course ever given in the city.

Â