Recreation for Youth In Short Supply

On a Friday afternoon in Prospect Park, a Little League team looking to practice finds that all the diamonds are full. In the South Bronx, a principal says her students go home after school and stay indoors because there’s no safe place to play outside. Parents wait on line for hours to sign up their children for private swim classes, if they can afford them, unless they live in one of the few neighborhoods with a public pool.

Ask parents about sports and recreation in New York City, and they are likely to say, "There’s not enough." Whether in minority neighborhoods that have disproportionately fewer parks and sports fields or in affluent areas with a growing demand for the kind of sports programs found in the suburbs, there are not enough facilities and programs to meet the needs of the city’s 1.5 million school age children.

Addressing these needs has become increasingly important as a growing body of research demonstrates that exercise and organized recreation can promote the healthy physical, social, and emotional development of children.

A 1996 report by the U.S. Surgeon General found multiple health benefits from engaging in regular physical activity, including weight loss and a reduced risk of diabetes, cancer, and heart disease. A study by the Department of Education found that 43 percent of New York City students from kindergarten through fifth grade are either overweight or obese. Obesity rates were highest in central Brooklyn, East and Central Harlem, and the South Bronx, low-income areas with few parks and recreational facilities.

Sports and organized recreational activities can also have a positive impact on social and emotional development as well as educational achievement. Teens who participate in organized recreational activities are less likely to drink alcohol, take drugs, or get pregnant. In several cities, the availability of recreation for youths has been found to lower crime rates. In Fort Worth, Texas, for example, crime fell 28 percent within a one-mile radius of community centers offering midnight basketball, but rose an average of 39 percent around five other centers that did not have the program. Studies have also shown that students who participate in physical activity on a regular basis do better in school.

The Decline Of Recreation in New York City

Parks have traditionally played a major role in providing sports and other recreation to city dwellers, especially youth. Under the City Charter, the New York City Department of Parks and Recreation has the "power and duty" to build and operate recreational facilities and offer programs, as well as to review and coordinate recreational activities conducted by other city agencies and to make agreements with government or private organizations for that purpose.

Advocates say that the department has been hampered in this goal by inadequate funding and by the low priority that the city placed on recreation for many years.

For decades, New York City let its recreational infrastructure crumble, both in the parks and in the schools. Beginning in the mid-1970s, the city all but eliminated funding for school sports and lowered the priority of physical education and fitness in the schools. Until recently, most high school teams and coaches have had to fend for themselves on bumpy, litter-strewn fields, buying their own uniforms and equipment and scraping up cash for transportation.

New York City’s schools once produced a steady crop of athletes for the major leagues, but by the 1990s the city had the lowest percentage of students participating in team sports of all the nation’s big cities, according to a 1999 New York Times series, Dropping the Ball (in pdf format) .

During that time, funding to maintain the city’s parks, courts, and fields also declined, reaching a low after the fiscal problems of the early 1990s, when the city shuttered recreation centers and let baseball and soccer fields wear down to dirt and rocks. The city built almost no new recreational facilities between the 1970s and the 1990s. Data compiled by the Center for Park Excellence at the Trust for Public Land show that New York City has fewer recreation centers, pools, and tennis courts per capita than nearly every large city in the country.

Although things have improved tremendously over the last decade, there are still fields and courts that are not in good condition, especially in the smaller parks in the outer boroughs. The 2005 Report Card on Parks, an annual survey of neighborhood parks conducted by the advocacy group New Yorkers for Parks, graded 29 percent of athletic fields and 33 percent of courts unacceptable for maintenance work.

Sports on the Rebound

In recent years, the city has increased capital funding for building and restoring sports fields and other facilities. The private sector has also been pinch-hitting for the government, providing the energy, expertise, and funding to fill gaps in the city’s recreation network, particularly in the city’s poorer neighborhoods.

The parks department has fixed up soccer, baseball, and football fields all over the city. On more than 40 fields, it has replaced grass (or what was left of it) with more durable artificial turf, and plans to convert 35 more. "As fast as we can build them," said Parks Commissioner Adrian Benepe, "they fill up, like building highways."

In April, the department inaugurated a $42 million track-and-field stadium on Randall’s Island, with half of the cost raised privately by the Randall’s Island Sports Foundation, including a $10 million naming sponsorship by financier Carl Icahn.

More new recreation centers have been opened or are in the works since the late 1960s or early 1970s, said Commissioner Benepe, who ticked off a list including the reopening of the Chelsea center after three decades; the near completion of another center in Flushing, Queens; the new nature center in the Staten Island Greenbelt; and the construction of a senior center in Marine Park.

If the city succeeds in its bid to play host to the 2012 Olympics, dozens of new facilities will be built or renovated, although there is debate about whether, when the Olympics are over, there will be enough demand for, and the city will be willing to maintain, such specialized venues as a shooting center, a whitewater course, and an enclosed bike track.

To meet some of the most pressing recreational needs of the city’s youth, a number of nonprofit groups have stepped up to the plate:

- Take the Field , founded in 2000 by three businessmen and philanthropists in response to the New York Times series about the decline of school sports, has rebuilt decrepit fields at 43 city high schools. The five-year effort, with $35 raised by Take the Field matched by $99 million from the Department of Education, is about to conclude after reaching the goal of fixing all the fields the group identified as in need of repair.

- In neighborhoods with the greatest need for parkland, the New York City Spaces program of the Trust for Public Land is taking the asphalt yards of elementary and middle school yards (some formerly used as parking lots) and turning them into multiple use parks. The yards, which have space for active sports, quiet activities and greenery, are open to the community outside of school hours. The organization has built 12 parks so far and recently entered into a $25 million agreement with the Department of Education to build 25 more, providing a quarter of the funding and overseeing the design and construction.

- New York Restoration Project, founded by Bette Midler to restore parks in disadvantaged neighborhoods, led the effort to transform a polluted site into a park at Swindler Cove on the Harlem River in Upper Manhattan. It also raised funds to build a floating boathouse anchored off the park, the first new community boathouse in the city in nearly 100 years. Rowing programs run by the group are introducing the Olympic sport to inner-city youths. The boathouse also provides a home for dozens of rowing teams from schools all over the city.

A Patchwork of Programs

The parks department has focused mainly on building and maintaining the infrastructure for sports, either directly or through concessions. Commissioner Benepe said, "The primary way we provide recreation is by creating facilities — clean, safe and well-run —that allow other groups to program them."

In the absence of a coordinated citywide recreation program, possibly hundreds of different organizations have developed programs to fill the gap, including volunteer sports leagues, neighborhood-based organizations, school and after-school programs, private non-profit groups, and profit-making recreational centers.

Per capita and as a percentage of its total budget, the New York City parks department spends less on programming (including sports, nature, art and other recreational activities) than most other major U.S. cities, according to data compiled by the Center for Park Excellence. According to the Independent Budget Office, in 2004 parks department recreation spending totaled just $16 million, out of an operating budget of approximately $260 million. Of that amount, about $9 million came from the state and federal governments and other city agencies and private sources. This does not include privately run recreation programs whose funding is not channeled through the parks department.

Funding for full-time recreation staff has fallen 69 percent since 1980, according to the parks advocacy group New Yorkers for Parks, although some of the difference has been made up by seasonal and temporary employees, including the job-training program workers who now make up the majority of the parks department work force.

Funding, Places and People All In Short Supply

Every year at budget time, there is uncertainty about funding for the playground associates, who keep the playgrounds clean and safe and organize activities in the summer. Typically, the mayor’s proposed budget reduces the number of positions for these and other seasonal workers and the City Council eventually restores them. At present, there are 171 playground associates for the city’s 991 playgrounds, according to the parks department.

"There’s a short supply not only of places to play but of people to supervise," said Maura Lout, research director at New Yorkers for Parks. The difficulty of getting a complete picture of recreation in the city because there are so many different providers, Lout said, "speaks to the dilemma."

Although some wealthier parts of the city, as well as formerly industrial areas like Tribeca, lack recreational fields and programs, residents in these neighborhoods tend to have the time and money to sign their children up for private classes and for sports leagues outside the immediate neighborhood. Some families in affluent areas of Brooklyn, for example, don’t think twice about enrolling their kids in a hockey program at the for-profit Chelsea Piers in Manhattan.

Targeting Poorer Neighborhoods

In large part because of the lack of facilities, the largest gaps in recreation programs are in the poorer neighborhoods with mostly minority or immigrant residents. In these areas, the cost, time and travel involved in getting to activities outside the immediate neighborhood are significant barriers to participation in many sports.

The parks department has made an effort to target its limited recreational resources to youth in these neighborhoods. Benepe noted that all of the department’s recreation programs for children, from swimming lessons to nature walks, are free.

The department organizes several athletic leagues and tournaments, often with support from corporate or non-profit partners. One innovative program directed toward underserved youth is the Star Track youth cycling and mentorship program in the newly renovated Kissena Velodrome in Queens. "Shape Up New York," a program run with the city health department, offers exercise for all ages at ten locations with high rates of high obesity and diabetes.

Free instruction in tennis, golf and track and field is also available at a number of parks from the City Parks Foundation, an independent non-profit that supports parks without access to private resources.

Working With The Schools

The parks department has also begun to coordinate its efforts with the Department of Education. "This is the first time in recent memory, maybe ever, that the parks and education departments are actually sitting down and talking to each other," said David Rivel, executive director of the City Parks Foundation.

Benepe said that with so many new schools being opened, the two departments have been discussing the use of park facilities during the day for physical education. They have also talked about expanding learn-to-swim programs using pools operated by both the schools and parks, as well as by colleges, non-profits and other organizations. "We could probably teach every kid how to swim if we put our minds to it," Benepe said. "If I could do one thing in the next four years it would be to teach every child, if not how to swim, at least to know what to do if you go in the water."

Under the leadership of Chancellor Joel Klein, there has been a new emphasis on fitness at the Department of Education. The department hired its first citywide director of fitness, Lori Benson; began providing professional development for physical education teachers; and instituted a new citywide physical education curriculum that emphasizes health-related fitness. With $1 million each from The Sports and Arts in Schools Foundation and the Snapple sponsorship, the department expanded a middle school sports and fitness program it piloted last year to 180 schools, many of which use parks for practice and games. "We are in the midst of a complete renaissance of the physical education program, which has not seen a lot of support over the last few decades," Benson said.

"There is a long way to go," said Rivel, "but things are clearly going in the right direction."

Anne Schwartz, in charge of the parks topic page since its inception in 1999, is a journalist who specializes in environmental issues.Â

Anne Schwartz, in charge of the parks topic page since its inception in 1999, is a journalist who specializes in environmental issues.Â

Recycling

Related: |

Listening to Mayor Michael Bloomberg and New York City Council Speaker Gifford Miller fight over garbage this month, the casual observer could be forgiven for thinking that the mayor’s entire citywide plan for garbage centered on a single pier on the Upper East Side. The development of trash policy has recently gotten bogged down over the mayor’s call to use several such piers as places for garbage trucks to unload onto barges. The dispute reached a climax on June 22nd when Miller failed to block the opening of the so-called marine transfer station in his district.

But with this diversion out of the way, officials and environmental advocates are turning back to the central issues of a plan that is rich in details on how to move the city's trash around, but, critics say, short on everything else.

“It’s our hope that the controversy is over and we can get back to the overall business of this plan, which is how do we deal with the rest of this 50,000 tons per day of waste,” said Eddie Bautista of the Organization of Waterfront Neighborhoods.

In the past, the city has dealt with waste by burning it, or burying it. Now Bloomberg is focusing on shipping it away. But the City Council has published its own plan that lists recycling as its major priority, and criticizes the mayor’s plan for failing “to put forward any real programs or policies that would reduce waste and increase recycling.”

Councilmember Michael McMahon, head of the council’s sanitation committee, will soon begin negotiating with the mayor over the council’s concerns. His hope is that by September a compromise plan will be worked out -- and that it will prominently feature recycling.

ARE NEW YORKERS RECYCLERS?

In theory, increasing the amount of garbage that is recycled is a goal that everyone can agree on. But how to do so is not necessarily simple, and officials differ on how much recycling the city can reasonably expect.

Currently, about 20 percent of residential waste in New York is recycled. City life poses serious challenges for those planning ways to raise this rate. Most New Yorkers live in apartments where there is often little space to set up bins to separate garbage. And although residents are legally required to recycle, apartment-dwellers are relatively invulnerable to tough enforcement measures, because it’s hard to find out who in a large apartment building isn’t recycling in order to fine them.

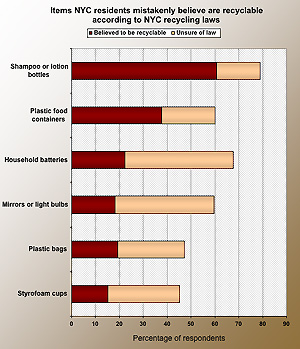

Further, many New Yorkers are confused about what is recyclable. A recent survey conducted for Gotham Gazette by Baruch College's eTownPanel found that about 85 percent of city residents knew that newspapers are recyclable, but less than half knew that aerosol cans are, and only about 40 percent knew that wire hangers are. At the opposite end, about 40 percent knew that plastic deli containers are NOT recyclable, and a mere 20 percent knew that they cannot recycle shampoo and lotion bottles. (For details on the survey and to see charts, click here)

Some believe that a mixture of education and enforcement could significantly raise the rate of recycling in the city, but Mayor Bloomberg is skeptical that these will make much difference.

“The more you recycle the better off you are,” he told WABC-FM earlier this month. “But most [of the city’s waste] is going to get thrown out.”

THE MAYOR’S ATTITUDE: SKEPTICAL OF RECYCLING

The mayor’s attitude towards recycling has displeased recycling advocates in the past. Facing a daunting budget gap in 2002, the mayor decided recycling was a luxury the city could not afford. The city suspended its glass and plastic recycling programs.

It wasn’t the first time that the city had cut back on recycling efforts in tough times. When the environmental benefits of recycling are measured against its economic drawbacks, the economics generally win out.

“Whenever something bad happens, recycling gets pushed back,” said Carmen Cognetta, legal counsel to the City Council’s solid waste committee.

Recycling has always been vulnerable to budget cuts because historically it has been more expensive that dumping garbage in landfills. While taking trash to a landfill costs significantly more than it does to take it to a recycling plant, the higher cost of collecting recyclables more than offsets these savings.

Advocates have long hoped to develop a way to make recycling as cheap as waste disposal. If achieved, this goal of “cost parity” does work to protect recycling programs. The city didn’t consider eliminating paper recycling in 2002, for instance, because it was actually getting paid by private companies for the recyclable paper, rather than having to pay.

THE MAYOR'S PLAN: MAKING RECYCLING PAY OFF

The mayor's overall garbage plan calls for the city to load its waste onto rail and barges and ship it out of the city, instead of relying as heavily on trucks as the city does now.

Environmentalists and activists from low- income neighborhoods have thrown their support behind the plan, because it decreases the city’s reliance on trucks, and spreads the burden of waste management throughout the city. The main criticism of the plan has been that it does not address where to send the trash, thus doing little to deal with the city’s fundamental trash related problem: its reliance on increasingly pricey landfills in distant places. (report in .pdf format)

For recyclables, however, Bloomberg’s plan does identify what it says is a good place to send waste. The city has forged a long-term relationship with recycling company Hugo Neu, in order to secure stable, favorable rates. As incentive to sign the 20-year contract, the city has agreed to invest $25 million to help Hugo Neu build a recycling facility in Sunset Park. Savings from the terms of the contract, the city believes, will more than offset the cost of the plant.

As the cost of recycling decreases, the cost of waste disposal will be increasing, thanks to the capital investment necessary to make the transition to new forms of transportation. This, some see as a good thing.

“This short-run increase in waste disposal costs, coupled with a new contract that lowers the fee paid for processing the city’s recyclables, alters the economics of waste management increasingly in favor of recycling as a cost-competitive alternative to disposal,” wrote Elisabeth Franklin and Preston Niblack of the Independent Budget Office in a recent analysis. (report in pdf format)

The analysis concludes that, all things being equal, the mayor’s plan will make the cost of recycling roughly equal to that of waste disposal.

While Bloomberg’s plan may end up creating a strong financial incentive to recycle, critics still deride its lack of a coherent recycling strategy.

"Exporting trash is one little piece of solid waste management. The city has a golden opportunity to commit in writing to innovative waste prevention, reuse, and recycling initiatives,” said Majorie Clarke, co-chair of the New York City Waste Prevention Coalition. “That's the guts that they're missing."

THE CITY COUNCIL’S ALTERNATIVE

Are New Yorkers Recyclers? Click here for details and charts |

The City Council aims much higher than the mayor in terms of recycling. Bloomberg’s goal is to have 26 percent of residential waste be recycled by 2010 and a 33 percent residential recycling rate by 2024. The council plan is much more ambitious, calling for an increase in residential recycling from 20 to 25 percent by 2007, and by 2015 a combined residential and commercial recycling rate of 70 percent.

Increasing recycling rates not only has environmental benefits, it has economic advantages as well. The more residents can be taught what is recyclable -- and either encouraged or forced to do it -- the cheaper recycling becomes. Collecting garbage is less expensive than recycling because the same truck can gather more tons of garbage per route than it can of recyclables. This is partially due to the relatively low weight of recyclables – plastic weighs less than food waste. But the more recycling that ends up on each curb, the less it costs to collect each ton of it.

“If the city is successful in increasing recycling beyond recent levels, it may even become the cheaper alternative, creating a strong incentive to promote recycling as a way to hold down the total cost of waste management,” wrote Franklin of the Independent Budget Office. (report in pdf format)

The mayor’s plan brushes over this potential; there are few specific ideas for increasing recycling rates. By contrast, the council’s plan calls for establishing a division in every community board that will tailor recycling programs to the local level. A new city agency would oversee this, leaving the Sanitation Department – which proponents of the plan describe as insufficiently committed to recycling – out of all recycling education and outreach programs.

"[Recycling] is never going to flourish under Sanitation," said Cognetta.

But Benjamin Miller, former director (and current critic) of policy planning for the Sanitation Department and author of Fat of the Land, a history of the city’s garbage, doubts whether the council’s plan will be effective. Any recycling plan should set a single standard for the entire city, he says, rather than relying on individual efforts in each neighborhood. And the best way to have a citywide plan is to keep a single agency in charge of all waste issues.

“The plan proposes what I would argue are likely to be quite inefficient systems [that] reflect a flawed understanding of how a recycling system should be designed,” he said. “We have to keep it simple.” Miller believes the best way to increase recycling is to charge people for the amount of garbage they throw out, creating an incentive to reduce the amount of waste they produce by, for example, recycling more.

The council’s plan also calls for increasing commercial recycling rates, and attempts to establish ways to recycle or reuse materials that today tend to end up in landfills.

ZERO WASTE: BEYOND RECYCLING

Some of these strategies were discussed at a recent conference of recycling advocates held in downtown Manhattan. The conference’s focus was to formulate programs that go beyond recycling by increasing the scope of what can be recycled and reduce consumption in general in a comprehensive strategy.

Attendees noted the success of initiatives in California and Maine that reduced waste at the source. They suggested more aggressive citywide compost recycling and a surcharge on plastic bags. A similar “plastax” law in Ireland reduced plastic bag use there by 90 percent.

The city would need help in implementing some of these ideas. Any new tax, for instance, would need to be approved by Albany.

The council has embraced these principles as part of its plan. It is currently considering several actions, including a bill that would require manufacturers to take back and recycle, reuse or properly dispose of a percentage of the electronics they sell. Another resolution calls on the state to pass a bill that would expand the bottle deposit to more products.

Jordan Barowitz, a spokesperson for the mayor, told the New York Times that the administration is willing to consider substantive changes to its plan, and specifically cited adding measures to increase recycling. But council’s plan, he said, was “a gimmick. It doesn’t advance the negotiations at all.”

Garbage plans in New York are often written and rarely implemented, and there is no guarantee that the council and the mayor’s negotiations this summer will end up producing anything resembling either of their plans. But if the officials can navigate the ever-tricky politics of garbage, recycling advocates see the potential for an economic and environmental payoff in the ideas currently on the table.

Â

Are New Yorkers Recyclers? A Survey of Habits and Attitudes

Eighty-two percent of New Yorkers say that they recycle “almost always” or “most of the time” at home, according to a survey conducted by Baruch College's eTownPanel for Gotham Gazette this month. Only five percent say that they never recycle. Fifty-six percent said they recycle more now than they did five years ago.

But they also express confusion about what they can and cannot recycle. While 83 percent of respondents knew they could recycle newspapers, only 40 percent knew that wire hangers were recyclable, and less than half knew that aerosol cans were recyclable. Only 62 percent said they were either “very familiar” or “familiar” with the city’s recycling program overall, and 15 percent said they were “not familiar at all.”

Respondents seemed to see their own confusion as a result of the city’s poor performance in educating its residents about the recycling regulations. Sixty-six percent said that the government’s performance in education the public was either “fair” or “poor”. They were also skeptical of the government’s commitment. Over half of respondents said that the city was only “somewhat committed” or “not committed at all” to recycling, while only 11 percent felt the city was “very committed”.

The survey was conducted betweeen June 7 and June 14, 2005 of 150 New Yorkers.

Return to Recycling by Sam Williams and Joshua Brustein

Â