Siting The Power Plant at Newtown Creek

Krysia Holowacz knows dirty. A former resident of Eastern Europe who emigrated to the U.S. in the 1970s, she's seen what industrial pollution can do to a once pristine landscape.

So when she drives her car down a semi-paved street that dead-ends 12 feet above the blackened waters of Newtown Creek, the waterway that separates Greenpoint from Long Island City, it's hard not to notice the awe.

"Can you believe this?" asks Holwacz, rising out of the car, holding her arms wide, and struggling to be heard over a pair of cranes lifting demolished cars off a nearby scrap metal barge.

The view is, indeed, awe-inspiring. Picture the Thames River at its Dickensian worst, only replace the tanneries and rendering plants with asphalt recovery and waste transfer stations, and you'll get a pretty good idea. Fortunately, it's a view few New Yorkers ever experience. Nearly two centuries of continuous industrial development and the quirky street patterns of the Brooklyn-Queens border combine to make this one of the least-accessible portions of the city.

That's one reason Mayor Michael Bloomberg, in a radio address earlier this month, offered Newtown Creek as a compromise site for a new 1,100 megawatt TransGas Energy power plant. Originally slated for the East River side of the neighborhood, the plant has drawn stiff opposition from local groups and environmental advocates who would like to see the East River waterfront cleaned up.

SAVVY COMPROMISE, OR DEVIL'S BARGAIN

Politically speaking, the mayor's compromise is a savvy move. Exchanging one site for another opens up the two mile Williamsburg-Greenpoint waterfront to residential redevelopment -- a move the mayor thinks will lure billions of dollars into the local economy. At the same time, it offers an easy solution to the city's pressing energy needs.

But for local activists like Holawacz, who lives in Greenpoint, the compromise is an environmental equivalent of the devil's bargain: As much as she wants a clean riverfront with more open space for parks, Holowacz, a community liaison for the Newtown Creek Water Pollution Control Plant who already fields plenty of complaints over that plant's ongoing expansion, recoils at the thought of adding yet another source of toxic emissions to this already-beleaguered corner of Greenpoint.

"This community is inundated," says Holowacz. "We get all the smell and all the paper and all the scrap metal. You can't put everything the city needs into one corner."

Officially, the decision on where to put the TransGas plant isn't the mayor's to make. That power resides at the state level, where Governor George Pataki has expressed support for new power plants as a way to meet the city's surging energy demand and decrease dependence on the regional grid. In May, the mayor's office threw its weight behind the neighborhood groups and developers who have opposed the siting of a power plant near Bushwick Inlet on the grounds that it would foil ongoing efforts to redevelop the Greenpoint-Williamsburg riverfront from industrial to residential use.

"This administration recognizes the need for new power plants and transmission lines," noted Daniel Doctoroff, deputy mayor for economic development and rebuilding, in a July 15 editorial for the Daily News." [But] when a power plant comes into conflict with a historic chance to rezone the waterfront to develop a 2-mile waterside walkway and create much-needed housing (both affordable and market-rate), it is in the city's best interest to find a more suitable location to benefit all parties."

In the final week of September, the mayor's office thought it had just that when it talked ExxonMobil, current owner of a derelict storage facility located on Kingsland Ave. a half mile downstream from the Kosciusko Bridge, into possibly selling the lot to TransGas as an alternate site.

SITE OF LARGE OIL SPILL

The deal is a tenuous one. The new site carries heavy legal baggage. In the 1950s and 1960s it was the site of the nation's largest underground oil spill; more than 17 million gallons seeped out of tanks and pipes and into an underground aquifer, a multi-year discharge that wasn't detected until the Coast Guard noticed a major oil plume in the creek in the late 1970s. In 1989 Mobil (now ExxonMobil) assumed cleanup responsibilities but according to an August report in the Polish Daily News has removed only about two million gallons to date. At that rate, the site will be fully remediated by 2030.

"You're talking about a discharge larger than the Exxon Valdez," says Riverkeeper legal investigator Basil Seggos, likening the 52 acre site to the famous 11 million gallon oil spill in Alaska in 1991. "You're not just talking about water pollution. You're talking about hydrostatic pressure of a new plant and trucks possibly extending the plume.

Neighborhood activists have concerns beyond underground oil. For the last 15 years, Greenpoint and Williamsburg residents have been united in their effort to rezone and redevelop the two mile East River waterfront. To accommodate this rezoning, they've agreed to leave new industrial development along Newtown Creek.

"Every city has an industrial area, and we decided that is our industrial area," says Joe Vance, co- chair of the Greenpoint Waterfront Association for Parks and Planning. "We'd certainly like to see the pollution cleaned up, but we'd like to keep that area industrial. The city needs the jobs. There's lots of really good companies, there. We don't want to see them go."

DIVIDING THE COMMUNITY

At the same time, Vance and other rezoning advocates fear the psychological impact of adding a power plant to a neighborhood that is already dealing with the expansion of the Newtown Creek sewage treatment facility. Soon to be the city's largest, the plant and its many odors have already prompted grumbles over residents on one side of the neighborhood selling out their poorer neighbors on the other.

"What you're doing is dividing the community along McGuiness Avenue," says Community Board 1 rezoning task force chairman Christopher Olechowski. "If [the mayor's plan] goes forward, it sets up kind of an imbalance in the community. It favors a waterfront rezone for market rate development but leaves the other side of the community as sort of a second tier segment."

For this reason, community activists and their environmental allies around the city have been hesitant to endorse the mayor's compromise. Still, Olechowski says even silence can come across as a tacit endorsement compared to the relative outcry over the East River site.

"I haven't heard any strong voices from any of the elected officials saying, 'We won't tolerate this,'" Olechowski says. "Maybe it's something I've missed, but I haven't seen it, yet."

David Yassky, the councilmember whose district includes Greenpoint, opposes the original siting plan but has yet to give the mayor's compromise proposal much thought.

"If somebody wants to put a power plant on the Exxon Mobil site they're going to have to file hundreds of pages of documents on what the environmental impact's going to be," Yassky says. "At this point, it really isn't far enough along for me to be able to comment."

Neighborhood activists and environmental groups, meanwhile, are trying to make sure the issue doesn't get to that point. Riverkeeper is set to announce a fresh series of lawsuits aimed at companies it says are currently the leading polluters along Newtown Creek. Neighborhood activists, meanwhile, are recycling the same arguments used against the original plant site.

"Why not upgrade existing power plants just like they're upgrading the sewer plant?" says Holowacz, noting that a number of local, oil-burning plants could gain increased efficiency while reducing toxic emissions if they switched to natural gas as a fuel source. "It's basically the same law, and yet they're not doing it."

With the recent blackout, however, energy companies like TransGas hold a momentary edge. The city's demand for power is growing, and August's power outage will still be fresh in minds of voters going to the polls next November. Even though the outage was the result of supply problems outside the city, the time has never been better, politically at least, to push for local plants.

Vance says the neighborhood still has the strength to hold its ground even without the real estate developers that helped foil the East River site.

"Greenpoint used to be the weakest link," he says. "Politicians looking at a map wondering where they could put something and get the least fallout always pointed here. That began to change in 2000 with the ConEd/Keyspan plant vote."

At the same time, Vance says, it will take a concerted effort to make sure that neighbors who see riverfront redevelopment as a community-wide issue also see Newtown Creek's overloaded banks in a similar light.

"People throw around the term 'Not In My Backyard'," Vance says. "But the East River was our front yard, and we can't put anything more in the backyard, because it's full. I challenge anybody to find any community in the city that has more citywide projects like this."

The Sewer System

Sewage was probably the last thing on the minds of most New Yorkers during the August 14 blackout. But while millions of people struggled to get home or contact loved ones, city workers watched helplessly as untreated waste poured into the East River from a pumping station at Avenue D and East 13th Street. With no electricity, nothing could prevent the pressure of the water from pushing open the gates that control the discharge of untreated sewage and so it simply blasted out.

Other articles in this series:

|

By the time the power came back, 145 million gallons of raw sewage - water from toilets and sinks as well as storm runoff -- had flowed into the East River from 13th Street and another 345 million gallons had spilled from treatment plants along the Hudson River in Manhattan and Brooklyn.

Sewage accidents caused by blackouts are rare, of course. What most people do not realize, however, is that spills are quite common. Even after decades of expensive upgrades designed to curb pollution, raw sewage regularly pours into the waterways around New York City because the sewer system uses outdated technology.

Failing sewers are not a problem limited to New York City. On November 4, all voters in the state, including those in New York City, will be asked to approve a constitutional amendment (in pdf format). that would help some smaller upstate communities upgrade their wastewater facilities.

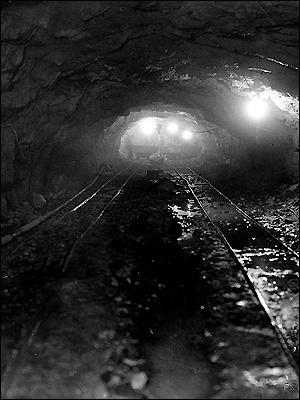

Construction of a Tunnel Sewer under 10th Avenue, 1938.

The measure will not help New York City control sewage spills or deal with the other problems of its massive sewer system. The city will be on its own when it comes to maintaining aged pipes, getting rid of environmentally harmful nitrogen, and dispelling the persistent belief that alligators live in its sewers.

FROM DITCHES TO DUMPING TO DECAY

New York City's sewer system, an engineering marvel and a murky source of urban legend, contains 6,600 miles of mains and pipes. Placed end to end, the city's sewers would stretch from Times Square to Fairbanks, Alaska and back. About 70 percent of that vast sewer system consists of combined sewers, which carry runoff from storms as well as waste from sinks, tubs and toilets. Some of the pipes still in use were laid 150 years ago when the modern sewer system began.

The city's first underground sewer of any kind goes back even further, to Dutch Colonial times, when a channel was dug down the middle of Broad Street and decked over. But well into the 19th century, most waste was typically disposed of in backyard outhouses, dumped into the gutter or poured into the ponds and streams that still existed in many parts of Manhattan.

Explosive growth in the early 1800s forced New York to finally confront its sanitation problems. In 1849, after years of haphazard planning and a series of deadly cholera outbreaks, the city started systematically building sewers. Between 1850 and 1855, New York laid 70 miles of sewers. In the second half of the 19th century, it expanded the network throughout the metropolis. By 1902, sewers served virtually all the developed sections of the city, and even tenement houses began offering private flush toilets. Today, sanitary sewers snake their way beneath all but a handful of outlying streets, and storm sewers crisscross just about every neighborhood.

THE JOURNEY

Each day, the city's 14 sewage treatment plants handle 1.3 billion gallons of wastewater, roughly 162 gallons for every man, woman and child who lives in the city.

Whenever you flush or turn on a faucet, the wastewater flows through pipes that lead to sewer pipes, called mains, in the street. Sewer mains are typically three to five feet in diameter. Runoff from rainstorms (and all the stuff that collects in the gutter) joins it in combined mains.

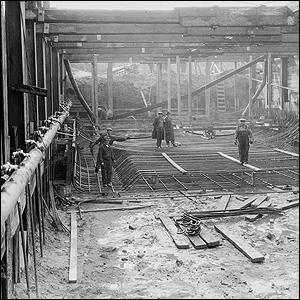

Building a Trunk Sewer in Queens, 1938

|

The sewage and runoff flow into a series of progressively larger pipes until they reach the wastewater treatment plant. The system relies almost entirely on gravity to keep the waste moving, although pumps help where the topography is difficult.

For decades, the waste simply went from the pipes out into the waterways surrounding the city. Most treatment plants in the city were not built until after World War II, and the last of these, the North River plant in West Harlem and the Red Hook plant in Brooklyn, were not completed until the late 1980s. As recently as 1986, all the sewage from the Upper West Side of Manhattan flowed untreated into the Hudson River. Ending that sewage flow played a big role in the river's rebirth.

Now the sewage goes to a plant for several stages of treatment. In the first stage, known as primary treatment, the water flows through filters and then collects in pools, where solids settle to the bottom so they can be removed. Until 1992, the city dumped about five million tons a year of these solids, known as sludge, in the ocean. It now dehydrates the sludge at special de-watering facilities that reduce its volume dramatically. The sludge is then either carted to dumps out of state or processed into materials that can be used for landfill cover.

In the secondary treatment stage, the wastewater is sent to large tanks where bacteria consume nutrients and organic materials. After the bacteria do their job and die a natural death, they are allowed to settle out of the water in tanks and then the cleaned water is released. One of the byproducts of the bacteria processing the waste is nitrogen, which mostly comes from the breakdown of ammonia in the sewage.

OVERFLOWING PROBLEMS

That is what happens when the system operates properly, but all too often it does not. Whenever there is a significant rainfall, sewer pipes overflow, and trash and chemicals pour directly into rivers and bays. Normally, all the waste in a combined system - toilets, sinks and runoff -- flows into sewage treatment plants. But when it rains heavily, all the the pipes tend to become overwhelmed and spill their contents. Each year, about 40 billion gallons of wastewater pours out of the combined system " a seemingly large amount but far less than in the past," city officials say

"Any time you get over a tenth of an inch of rain per hour, there are overflows," says Terry Backer of Connecticut-based Long Island Soundkeeper, an environmental group. "Oil, garbage, ethylene glycol [antifreeze], dog poop and everything in the gutters comes blasting out of the system, and then we tell our kids to go swimming in it."

Now that the city has upgraded its sewage treatment plants to comply with the federal Clean Water Act, it will focus on stanching such overflows and limiting the amount of nitrogen discharged from the sewer system into waters feeding Long Island Sound. "The key sewer-related issue right now for us is definitely the decrease of overflows," says Ian Michael, press secretary of the Department of Environmental Protection. The city has embarked on a 10-year overflow reduction program that will cost $2 billion, he says.

Environmentalists have been pressing the city about this. The current situation is "outrageous," Sarah J. Meyland, executive director of Citizens Campaign for the Environment, told The New York Times recently. "Across the board there often is a very casual feeling about allowing raw sewage back into the environment under sporadic circumstances, as if sewage is really not that bad."

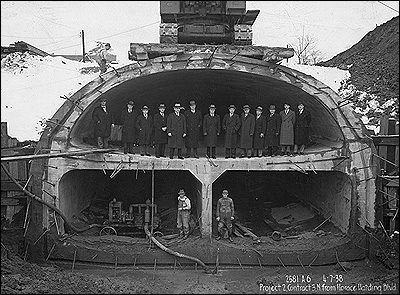

Construction Crew at a Storm Sewer in Queens, 1938

|

Many see the combined sewers as the culprit. Only about 800 U.S. cities still rely on combined systems. The rest, some 20,000 municipalities, carry wastewater and storm runoff in separate pipes. The separate sewer systems prevent overflows and are more efficient because treatment plants do not have to accommodate storm runoff along with wastewater.

But building separate sewers in New York would be prohibitively expensive. Instead the city is constructing huge underground reservoirs where the overflow can be held until water levels subside and the waste can be safely pumped into the treatment plants without spilling.

Poor equipment poses another problem. The 13th Street plant had emergency generators to prevent spills but they failed during the blackout. Some in the community have opposed the generators because the neighborhood already has a Con Edison plant in addition to the pump station. But the city is ready to install new backup power systems.

THE NITROGEN PROBLEM

The city is also under pressure to reduce the amount of nitrogen it discharges along with treated sewage water. Nitrogen feeds huge growths of algae, which deplete the supply of oxygen in the water as they die and decompose, choking fish and other marine life. Environmental groups say that excessive nitrogen levels in New York City's wastewater have undermined efforts by other Long Island Sound communities that have spent hundreds of millions of dollars to clean up discharges and restore the marine ecosystem.

One such group, Soundkeeper, filed suit in federal court in 1998 accusing the city of failing to comply with nitrogen regulations and trying to delay a clean up. After the states of New York and Connecticut joined the environmentalists' action, the city in late 2001 agreed to begin nitrogen reduction, using natural chemical reactions.

But some environmentalists think this is not enough. At a hearing before an administrative law judge in Nassau County on October 2, Soundkeeper argued that the city should be held to stricter standards under its permit to discharge wastewater. The city, which has invested heavily in nitrogen removal in recent years, says it is doing plenty and should be able to seek the most cost-effective solutions. The hearing process could take four to six months.

AGING EQUIPMENT

In the sewer pipes, age is a continual and critical issue. The heavily used system still includes 1850s-vintage pipes below parts of Lower Manhattan. Sewer workers regularly send remote-controlled video cameras through the pipes to try to spot leaks and cracks and patch or replace damaged pipes before they break. But replacing whole stretches of old pipes is not an option, because officials believe that even a major water or sewer main break is less disruptive than ripping up miles of streets to lay new pipes. "We know for a fact that they'll continue to last," Michaels says. "It is not just a matter of crossing your fingers and hoping they keep working."

The city is also repairing one of its oldest treatment plants, Sheepshead Bay, Brooklyn, where a fire in August damaged the odor-control system and sent foul-smelling gases wafting over the surrounding residential neighborhood.

The measure on the ballot this fall is designed to help smaller communities fund some of the projects New York City has already undertaken. If passed, it would allow counties and municipalities to exclude the cost of building or refurbishing sewers from municipal debt limits until 2014. Assemblymember Robert K. Sweeney of Suffolk County, who sponsored the measure in the Assembly, says it will help communities that have small tax bases by allowing them to borrow for sewer projects without having to postpone building roads and schools. The debt limit is pegged to the size of the tax base,

"In the past 10 years there have been less than two dozen communities statewide, most of them upstate, that have been covered by this," says Sweeney. The measure, which sailed through the state legislature earlier this year, renews a provision first enacted in 1963.

LATER, ALLIGATOR

Whatever the problems facing New York's sewer system, video inspections of the sewers do not turn up colonies of alligators.

Contrary to popular mythology, there are more alligators living in Manhattan apartments than underneath the city.

The alligator story is an old one, but it got a big boost in 1959, with the publication of Robert Daly's otherwise credible book, The World Beneath the City. Daly relied a bit too heavily on an imaginative former sewer inspector named Thomas May who said that, as he went on his rounds, he encountered reptiles of "alarming sizes."

A new sewer-related urban legend has been born in recent years. The story goes that marijuana, hurriedly flushed down toilets to keep it from police and prying parents, has taken root in the sewers. Fed by nutrient-rich sewage but deprived of sunlight, it mutated into an extremely potent albino form. Known as New York White, this pot is said to be incredibly expensive. That's because to harvest it, you have to get past, yup, alligators.

Natural Gas

The natural gas that boiled the water for a cup of tea on a stove in Queens Village last night began its journey near Nova Scotia some 140 million years ago. The muddy bottom of a lush swamp turned into something harder and began buckling. Plant and animal matter that had decayed and turned into methane and propane filled the gap underneath the buckled surface and remained there for eons.

Other articles in this series:

|

Not long ago, a drill bit finally hit the pocket to extract these ancient gases and pipelines brought them the thousand miles to the grills and stoves, as well as the furnaces, clothing dryers and power plants, of New York City.

The odyssey of natural gas is impressive. Only decades ago, the fuel was viewed as nothing more than a pesky byproduct of petroleum, a nuisance that made it more difficult to extract the "black gold" underneath.

Now natural gas itself has become a kind of gold. It's not just for breakfast anymore: Many city homeowners made the switch from oil to gas heat for their furnaces in the mid-1990s, and federal clean-air legislation pushed local power plants to do the same, with some wonderful results: cleaner facilities, better fuel efficiency, and less dependence on a worldwide marketplace dominated by OPEC oil ministers.

But as demand has risen, so too has cost. The federal Energy Information Administration predicted earlier this month that the average American family will pay nine percent more for natural gas heat this winter than last.

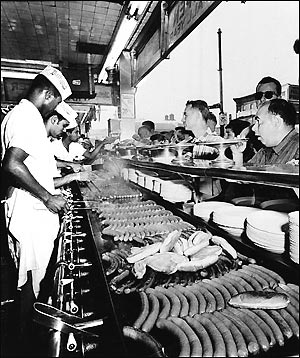

Cooking with natural gas at Coney Island, 1958.

This will still be less than for oil -- an estimated average of $841 compared to $927 -- but it is not likely to stay that way, according to New York State Assemblyman Paul Tonko, chairman of the Assembly Energy Committee. And there is a danger, Tonko says, in relying more and more on this one fuel source: "As natural gas becomes in larger measure the fuel of choice for both heating and electricity generation, we're creating a very risky situation for consumers."

THE JOURNEY

The term "natural gas" often leads to confusion. Some confuse it with the gasoline used in cars. But at room temperature, natural gas is just that, a gas, while gasoline is a liquid. Natural gas, says Ed Yutkowitz, a spokesman for Keyspan, can also be confused with the gas that lit New York's streets and fueled its stoves until the 1950s. That gas, which was highly toxic, came from superheating coal. But, beginning in the middle of the 20th century, companies began building pipelines to transport gas itself, providing for a far cleaner energy source.

The gas that Con Edison, Keyspan and smaller suppliers deliver to customers in New York City comes from places throughout the southwest United States and Canada -- a domestic marketplace impervious to foreign competition. Some of the gas has been piped down from the waters off Sable Island, a skinny piece of land about 100 miles off the southwest coast of Nova Scotia. Once known as "the graveyard of the Atlantic" because of the hazard it posed for ships, it is now home to six gas fields.

When the drill hits the pocket, the hot gas, suddenly liberated by the reduction in pressure, rises upward to the wellhead. At Sable Island, water is removed from the gas on off shore platforms before the gas goes via pipes to Goldboro, a small town that was once the scene of a gold rush and now hopes to profit from an energy boom. There, engineers filter out byproducts and impurities, such as sand and rock. Once processed, the gas is compressed and pushed down a new set of pipelines.

In some countries, the gas is chilled to minus 280 degrees Fahrenheit to get it into liquid form. Then it is loaded on tankers and shipped. But in the United States and Canada, the gas remains in its gaseous state.

Over the last century, more than a million miles of pipeline have been built in North America, connecting hundreds of natural gas wells in the Rockies, Gulf of Mexico and Appalachian Mountain regions to the burners on your stove. Like tributaries of a river, the pipelines keep feeding into other pipelines, the gas propelled along the route by pressure. Interstate pipelines, up to 42 inches wide, feature compressor stations every 50 miles that keep the gas pressurized. At top pressure, the gas moves at a speed of roughly 30 miles per hour.

At certain central locations -– so-called hubs in Louisiana, Illinois and Ontario -- commodities traders in suits and ties take over from the engineers in jeans and t-shirts. Buying and selling multimillion dollar contracts, they act as middlemen between the energy companies that extract the gas and the major utilities that use it to supply customers with heat in the winter and a little extra electricity in the summer. Since 1990, when the government deregulated the market, just about anybody with enough money can go into business as a natural gas middleman or speculator. Buying up cheap natural gas delivery contracts and reselling them whenever prices spiked transformed Houston-based Enron Inc. from a humble pipeline company into one of the most profitable companies of the 1990s, until greed helped precipitate its fall from grace.

THROUGH THE 'CITY GATE'

The New York Mercantile Exchange, or NYMEX, is the primary scene for buying and selling natural gas contracts. Once bought, these contracts can be resold or cashed in for delivery at the Henry Hub, a convergence point for six regional pipelines located in western Louisiana. Like the Dow Jones Industrial Average, the daily price of Henry Hub contracts serves as a benchmark for the overall cost of American natural gas.

Once a utility company or major manufacturer has purchased a natural gas contract for delivery, it must find a pipeline company to bring that gas to its own pipes and storage tanks.

Years ago, these pipeline companies played the role of wholesalers, buying and selling gas at a markup. Since deregulation, they've become more like interstate trucking companies, charging only for the cost of transportation. This cost varies depending on pipeline capacity. When demand jumps, pipelines deliver gas around the clock, raising the cost for last-minute, emergency deliveries.

Only four companies currently compete to deliver natural gas from the Henry Hub to the "city gate" — industry parlance for Con Ed and Keyspan's local pipeline systems. Of these four companies, one, Tulsa-based Williams Inc., is responsible for more than 50 percent of all natural gas delivered. If Williams were to lose one of its four feeder pipelines into the city because of a malfunction or terrorist attack, New Yorkers wouldn't go through anything as sudden or catastrophic as the August 14 blackout, but they would experience a sudden jump in energy prices.

While few worry about the overall long-term supply being in danger of depletion -- gas is a relatively abundant resource, and has a "large volume" of undiscovered reserves, according to the U.S. Department of Energy -- there is great concern about the current capacity of regional pipelines to bring enough gas to New York in order to meet the increasing local demand.

A number of new pipeline projects could boost the flow of natural gas into New York City. The 2002 State Energy Plan lists more than ten projects approved by the Federal Energy Regulatory Commission. "We're going to need more [system] capacity if we want more market growth," says Mike Scott, author of the State Energy Plan's chapter on natural gas infrastructure.

Karl Brack, spokesman for Columbia Gas Transmission, is more blunt: "There simply is not enough [pipeline] capacity to meet the needs of the region," says Brack, whose Virginia-based company is preparing to build a pipeline connecting downstate New York with a Canadian pipeline running under Lake Ontario.

When the gas crosses the "city gate," local distributors, such as Con Edison and Keyspan, add mercaptan, the chemical that gives gas that rotten egg smell. This is a safety measure; without such an additive natural gas is odorless and colorless so it would be impossible to detect a possibly deadly leak.

In New York City, the gas stays underground. It moves into local pipes called mains, running under streets and passing through emergency shutoff valves. One final branch, about an inch in diameter, brings the gas to the Queens Village home, where it may be used for heating and drying clothes, as well as cooking.

Although Con Edison and Keyspan divide the city in terms of service — Con Edison serving Manhattan, Bronx and portions of Queens, Keyspan serving the remainder — New York is one of the few states where residents have the ability to choose their local gas provider. In other words, outside companies can deliver gas via Keyspan's or Con Edison's local pipeline system just as telephone companies can deliver long distance service via Verizon's local telephone network. But, to date, this competition has played out more on paper than in reality.

THE MARKET

New York, once a laggard in natural gas demand, now accounts for six percent of nationwide natural gas consumption, compared with five percent for petroleum and one percent for coal, according to the New York State Energy Research and Development Association.

The increased demand has contributed to the upward drift in prices and the growing concern about local supply. New Yorkers already reeling from the August blackout could be in for a second shock this winter. If cold weather forces Con Edison and Keyspan to deplete their winter reserves, New Yorkers could see their winter energy bills spike even higher than they did three winters ago. Then, the utilities had to supplement their supplies and were forced to pay two to three times the normal wholesale rate. As always, the utilities passed the cost along to their customers, who wondered why their electric and gas bills had suddenly doubled.

To avoid yet another energy ambush, government agencies and utility companies are slowly getting the word out about the potential for higher bills this winter.

If we get a repeat of the warm 2001-2002 winter, energy prices should remain elevated but stable. If we get a repeat of last winter's cold weather, things could get ugly even for heating oil users. With natural gas now qualifying as the number one fuel for local power plants — 28 percent of all electricity used in the state comes from generators powered by natural gas, says the New York State Energy Research and Development Association — everyone is a natural gas user nowadays.

That's quite a change from the days when oil workers treated natural gas as garbage.