The Alarming Report About The EPA's Response To 9/11

When the Environmental Protection Agency's Office of the Inspector General released its long-awaited report on the agency's response to the September 11, 2001 terrorist attacks, reporters seized on a startling allegation -- that White House officials and former EPA director Christine Todd Whitman conspired to downplay the environmental impact of the World Trade Center collapse in the days immediately following the attacks. They offered reassurance without the proper evidence to do so.

But those who take a tour through the remaining 164 pages of the report might come out even more outraged and alarmed. If anything, the recent uproar over what the White House suppressed and when it suppressed it draws attention away from the report's deeper revelation, something Gotham Gazette writer Eric Goldstein noted in this space nearly a year ago. Though in many parts heroic, the city, state and federal government's collective environmental response to the September 11 attacks exhibited a glaring " leadership gap."

This gap is particularly troubling for New Yorkers. Though September 11 already ranks as the worst single-day environmental catastrophe to befall the city, it doesn't take much imagination to conjure up something that could be even worse. From the October, 2001, anthrax scare to ongoing concerns over a Chernobyl-level disaster at the upriver Indian Point nuclear power plant, New Yorkers are waking to the implications of treating the environment and public health as an afterthought during disaster recovery.

Step One: Closing the Leadership Gap

Two chapters of the report, about 20 pages total, defend the legality of the Environmental Protection Agency's behavior at and around Ground Zero, while at the same time chiding it for not being "proactive" enough in asserting its authority in various realms. One realm in particular, cleanup of indoor spaces contaminated by the attack, comes under special scrutiny. The report notes that in the first months after the attack agency press releases "deferred to the New York City Department of Health guidance even though EPA's position on indoor cleanup was different [from] the city's."

When it comes to explaining this institutional timidity, however, the report goes timid itself: "EPA does not have clear statutory authority to establish and enforce health-based regulatory standard for indoor air," the report notes. "Neither CERCLA [Comprehensive Environmental Response Compensation and Liability Act] nor NCP [National Contingency Plan] obligate EPA to undertake response actions."

Buried on page 27, this explanation may turn out to be one true smoking gun in the entire document. Edward P. Richards, professor and director of the Louisiana State University's Law, Science and Public Health program, offers a plain English translation.

"The feds aren't really set up to manage a crisis," says Richards. "They really depend on the locals."

Two years after the attacks, New Yorkers can look back on the events of September 11, 2001, in a less emotional light. In addition to soul-stirring acts of heroism, it is now easy to see the naked battle for political supremacy at the World Trade Center site in the minutes, hours and days following the first airliner impact.

It shouldn’t be too surprising that this battle favored the locals — former Mayor Rudy Giuliani, city ironworkers, the New York City Department of Design and Construction — over the visitors — the Federal Emergency Management Agency, the Occupational Safety & Health Administration, and the EPA. The raw emotions stirred up by the attacks prompted a can-do spirit which federal agencies were loathe to undermine.

Still, by deferring to local authority, mistakes were made. By January, complaints over the city's delegation of actual cleanup responsibility to individual owners and tenants in buildings surrounding Ground Zero prompted Jerrold Nadler, the U.S. Representative whose district includes Ground Zero, to cite a "gross disparity" in the EPA's handling of the Lower Manhattan cleanup compared with other contaminated sites around the country.

"New York was at the center of one of the most calamitous events in American history, and the EPA has essentially walked away," Nadler said in a February 11, 2002, testimony before the Senate Committee on Environment and Public Works. Nadler's outcry would lead to the creation of a multi-agency cleanup effort led by EPA. Still, complaints lingered, and it wasn't until August, 2002 that the agency launched a full building-by-building cleanup process.

Aside from federal reliance on local responders and local contractors, the report also downplays the agency's own second-tier status within the Bush Administration. It notes that in July of last year, the Bush Administration, via the Department of Homeland Security, designated the EPA as the primary agency "responsible for decontamination of affected buildings and neighborhoods" and "determining when it is safe to return to those areas" after a terrorist attack, but neglects to mention the already-overburdened Office of Criminal Enforcement, Forensics and Testing, the internal division that handles such matters.

In July of this year, a report in CongressDaily revealed that the Office of Criminal Enforcement, Forensics and Testing currently faces a backlog of more than 1,500 cases as the Bush Administration has denied repeated requests to boost the division's manpower from 200 to 400 agents. Six Democratic senators and Vermont Independent Senator James Jeffords subsequently issued a joint request that the EPA's Inspector General investigate whether even the former count was inflated by Bush staffers.

The EPA, in other words, may lacks the staff to be a major player in any post-disaster response scenario.

Step Two: Closing the Liability Gap

Admittedly, if EPA officials had declared the World Trade Center and much of Lower Manhattan a Superfund site on September 12, 2001, they would have faced far more heat then than they do now. Such assertiveness, however, might prove necessary in future situations where no single mayor or governor holds uniform jurisdiction.

It might also preclude what is already shaping up to be a cruel irony of the September 11 attacks: New York City residents, in addition to suffering the worst psychological and health effects of the September 11 attacks, may wind up paying the legal bill as well.

Professor Richards notes that the EPA, because of the judicial branch's traditional deference to the executive branch on matters of policy, provides a less inviting target for post-disaster legal claims than the City of New York.

"Getting damages out of the federal government is a pretty unusual circumstance," Roberts says. "It happens, but you have to show the government used negligence and it wasn't just a policy decision. After all, the word policy implies that you have some sort of tradeoff — public health vs. public security — that the government is taking into account when it makes a decision."

Because the EPA took a back seat to the New York City Departments of Health and Environmental Protection in the first months after the attacks, however, this shield has no effect. U.S. District Judge Alvin Hellerstein recently served notice that local government agencies will have less luck pleading "governmental immunity" when he gave the green light to a victims' lawsuit against the Port Authority of New York and New Jersey.

Is New York City next in line? Judging by the feisty response of Kenneth Becker, chief of the World Trade Center Unit in the New York City Law Department, the city is already preparing a major battle. Taking issue with the agency's attempts to shift the blame on issues such as respirator usage at Ground Zero and testing for concrete dust and other non-asbestos particles, Becker's rebuttals merit their own special 10-age appendix within the report.

"The City believes EPA Region 2's comment that it did not want to take a more assertive stance because it would create a confrontation is not valid," writes Becker. "In fact, when at a point in time during the Response Effort, EPA suggested that its functions be transitioned to a contractor, the City urged the EPA not to do this and to continue to maintain an on-site presence and be part of the team."

Jay Cohen, deputy chief of the Law Department's World Trade Center Unit, says the report reveals no evidence of city negligence. "To the contrary," Cohen writes, "the report demonstrates the proactive approach of New York City agencies, in particular the Department of Environmental Protection."

Even so, the conflicting views encased in the report remains a sore point. Was the EPA too deferential to local authority or was it too ready to leave its local counterparts in the toxic dust? The report suggests that, unless bureaucratic tensions are resolved, future environmental disasters may look far too much like September 11, 2001.

The Alarming Report About The EPA's Response To 9/11

When the Environmental Protection Agency's Office of the Inspector General released its long-awaited report on the agency's response to the September 11, 2001 terrorist attacks, reporters seized on a startling allegation -- that White House officials and former EPA director Christine Todd Whitman conspired to downplay the environmental impact of the World Trade Center collapse in the days immediately following the attacks. They offered reassurance without the proper evidence to do so.

But those who take a tour through the remaining 164 pages of the report might come out even more outraged and alarmed. If anything, the recent uproar over what the White House suppressed and when it suppressed it draws attention away from the report's deeper revelation, something Gotham Gazette writer Eric Goldstein noted in this space nearly a year ago. Though in many parts heroic, the city, state and federal government's collective environmental response to the September 11 attacks exhibited a glaring " leadership gap."

This gap is particularly troubling for New Yorkers. Though September 11 already ranks as the worst single-day environmental catastrophe to befall the city, it doesn't take much imagination to conjure up something that could be even worse. From the October, 2001, anthrax scare to ongoing concerns over a Chernobyl-level disaster at the upriver Indian Point nuclear power plant, New Yorkers are waking to the implications of treating the environment and public health as an afterthought during disaster recovery.

Step One: Closing the Leadership Gap

Two chapters of the report, about 20 pages total, defend the legality of the Environmental Protection Agency's behavior at and around Ground Zero, while at the same time chiding it for not being "proactive" enough in asserting its authority in various realms. One realm in particular, cleanup of indoor spaces contaminated by the attack, comes under special scrutiny. The report notes that in the first months after the attack agency press releases "deferred to the New York City Department of Health guidance even though EPA's position on indoor cleanup was different [from] the city's."

When it comes to explaining this institutional timidity, however, the report goes timid itself: "EPA does not have clear statutory authority to establish and enforce health-based regulatory standard for indoor air," the report notes. "Neither CERCLA [Comprehensive Environmental Response Compensation and Liability Act] nor NCP [National Contingency Plan] obligate EPA to undertake response actions."

Buried on page 27, this explanation may turn out to be one true smoking gun in the entire document. Edward P. Richards, professor and director of the Louisiana State University's Law, Science and Public Health program, offers a plain English translation.

"The feds aren't really set up to manage a crisis," says Richards. "They really depend on the locals."

Two years after the attacks, New Yorkers can look back on the events of September 11, 2001, in a less emotional light. In addition to soul-stirring acts of heroism, it is now easy to see the naked battle for political supremacy at the World Trade Center site in the minutes, hours and days following the first airliner impact.

It shouldn’t be too surprising that this battle favored the locals — former Mayor Rudy Giuliani, city ironworkers, the New York City Department of Design and Construction — over the visitors — the Federal Emergency Management Agency, the Occupational Safety & Health Administration, and the EPA. The raw emotions stirred up by the attacks prompted a can-do spirit which federal agencies were loathe to undermine.

Still, by deferring to local authority, mistakes were made. By January, complaints over the city's delegation of actual cleanup responsibility to individual owners and tenants in buildings surrounding Ground Zero prompted Jerrold Nadler, the U.S. Representative whose district includes Ground Zero, to cite a "gross disparity" in the EPA's handling of the Lower Manhattan cleanup compared with other contaminated sites around the country.

"New York was at the center of one of the most calamitous events in American history, and the EPA has essentially walked away," Nadler said in a February 11, 2002, testimony before the Senate Committee on Environment and Public Works. Nadler's outcry would lead to the creation of a multi-agency cleanup effort led by EPA. Still, complaints lingered, and it wasn't until August, 2002 that the agency launched a full building-by-building cleanup process.

Aside from federal reliance on local responders and local contractors, the report also downplays the agency's own second-tier status within the Bush Administration. It notes that in July of last year, the Bush Administration, via the Department of Homeland Security, designated the EPA as the primary agency "responsible for decontamination of affected buildings and neighborhoods" and "determining when it is safe to return to those areas" after a terrorist attack, but neglects to mention the already-overburdened Office of Criminal Enforcement, Forensics and Testing, the internal division that handles such matters.

In July of this year, a report in CongressDaily revealed that the Office of Criminal Enforcement, Forensics and Testing currently faces a backlog of more than 1,500 cases as the Bush Administration has denied repeated requests to boost the division's manpower from 200 to 400 agents. Six Democratic senators and Vermont Independent Senator James Jeffords subsequently issued a joint request that the EPA's Inspector General investigate whether even the former count was inflated by Bush staffers.

The EPA, in other words, may lacks the staff to be a major player in any post-disaster response scenario.

Step Two: Closing the Liability Gap

Admittedly, if EPA officials had declared the World Trade Center and much of Lower Manhattan a Superfund site on September 12, 2001, they would have faced far more heat then than they do now. Such assertiveness, however, might prove necessary in future situations where no single mayor or governor holds uniform jurisdiction.

It might also preclude what is already shaping up to be a cruel irony of the September 11 attacks: New York City residents, in addition to suffering the worst psychological and health effects of the September 11 attacks, may wind up paying the legal bill as well.

Professor Richards notes that the EPA, because of the judicial branch's traditional deference to the executive branch on matters of policy, provides a less inviting target for post-disaster legal claims than the City of New York.

"Getting damages out of the federal government is a pretty unusual circumstance," Roberts says. "It happens, but you have to show the government used negligence and it wasn't just a policy decision. After all, the word policy implies that you have some sort of tradeoff — public health vs. public security — that the government is taking into account when it makes a decision."

Because the EPA took a back seat to the New York City Departments of Health and Environmental Protection in the first months after the attacks, however, this shield has no effect. U.S. District Judge Alvin Hellerstein recently served notice that local government agencies will have less luck pleading "governmental immunity" when he gave the green light to a victims' lawsuit against the Port Authority of New York and New Jersey.

Is New York City next in line? Judging by the feisty response of Kenneth Becker, chief of the World Trade Center Unit in the New York City Law Department, the city is already preparing a major battle. Taking issue with the agency's attempts to shift the blame on issues such as respirator usage at Ground Zero and testing for concrete dust and other non-asbestos particles, Becker's rebuttals merit their own special 10-age appendix within the report.

"The City believes EPA Region 2's comment that it did not want to take a more assertive stance because it would create a confrontation is not valid," writes Becker. "In fact, when at a point in time during the Response Effort, EPA suggested that its functions be transitioned to a contractor, the City urged the EPA not to do this and to continue to maintain an on-site presence and be part of the team."

Jay Cohen, deputy chief of the Law Department's World Trade Center Unit, says the report reveals no evidence of city negligence. "To the contrary," Cohen writes, "the report demonstrates the proactive approach of New York City agencies, in particular the Department of Environmental Protection."

Even so, the conflicting views encased in the report remains a sore point. Was the EPA too deferential to local authority or was it too ready to leave its local counterparts in the toxic dust? The report suggests that, unless bureaucratic tensions are resolved, future environmental disasters may look far too much like September 11, 2001.

The Power Broker Revisited

At a recent meeting in the Lower East Side about how to spend remaining federal funds to rebuild lower Manhattan, a group of protesters gathered outside, angry about how the money has been allocated so far. To rebuild, City Councilmember Margarita Lopez yelled, "you don't need a power broker. The only thing you need to do is talk to people in the community."

For many New Yorkers, the phrase "power broker" means one person: Robert Moses. And he wasn't known for talking to communities. He was known for "getting things done."

From 1924 until 1968, Moses built public works in the city and state, including seven city bridges, two tunnels under the East River, 658 playgrounds and 416 miles of parkways. He also destroyed neighborhoods, dislocating thousands, to make way for his expressways. His biographer, Robert Caro, wrote in The Power Broker that Moses was fond of saying, "When you operate in an overbuilt metropolis, you have to hack your way with a meat ax." and "You can't make an omelet without breaking eggs."

In the decades since Moses' day, planning in New York City shifted to a community review process, to give neighborhoods more of a say in their own future. This has also meant that far fewer huge public works get built. But as plans develop for massive public building projects in lower Manhattan, for the 2012 Olympic bid, and on the island's far West Side, some say that New York City could learn from Moses' methods, while others worry that the power broker's worst tactics may already be at work.

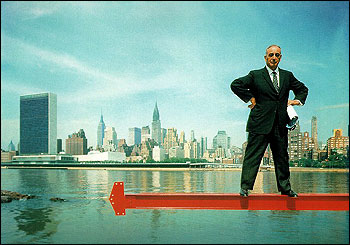

Robert Moses

In The Power Broker, Caro writes that Moses was "America's greatest builder. He was the shaper of the greatest city in the New World." New Yorkers never elected Moses to anything, but he was able to amass power as governor after governor and mayor after mayor appointed him to important positions - at different points in his career, Moses was head of state and city parks, chair of the city's slum clearance commission, construction coordinator, and once occupied 12 different positions simultaneously. Moses used the power of the public authority to sell bonds, build roads, collect tolls and put the money back in to new projects.

Moses fell from power in the late 1960s and died in 1981, but his influence hangs over many current debates. In fact, New Yorkers are now discussing the future of some of the projects that Moses himself built, including Lincoln Center, the cultural hub that Moses created as a 1960s urban renewal project. And in the South Bronx, community groups have created a plan to tear down the Sheridan Expressway, a 1.25 mile-long part of Moses' legacy.

| Reading NYC Robert Caro's biography of Robert Moses, The Power Broker, is Gotham Gazette's Reading NYC Book Club selection for August -- join us at the Borders bookstore at 100 Broadway (across from Trinity Church) at 6 p.m. on Wednesday, August 20 for a discussion of the book. |

Despite an incredible record of "getting things done," not everything that Moses proposed was built.

In fact, he lost a major public battle to build an expressway through lower Manhattan, after author and urban planner Jane Jacobs galvanized West Villagers and other lower Manhattan residents to stop the highway. The great builder also never succeeded in forging a road down Fire Island - in 1964, the Fire Island National Seashore was established instead. And Moses' Coliseum at Columbus Circle, which Caro called a "glowering exhibition tower whose name reveals Moses' preoccupation with achieving an immortality like that conferred on the Caesars of Rome," was torn down in 2000 to make way for the new Columbus Center.

Moses-sized Projects Today: Olympics and the West Side

But while the Coliseum may have fallen, the figure of Moses continues to inspire debates and influence projects today. When now deputy mayor Daniel Doctoroff and a group of developers, politicians and planners first assembled the bid to bring the 2012 Olympics to New York City, the New York Observer called the group "a hundred-headed Robert Moses... frustrated by decades of political paralysis and determined to resuscitate the long-vanished art of getting things built on a grand scale with brute political force."

When Moses was president of the New York World's Fair of 1964-65, he fought to turn the exposition's fairgrounds– shifting money around in secret, according to his biographer Robert Caro –into Flushing Meadows-Corona Park. When the park was dedicated, Moses said that the fair had "ushered in, at the very geographical and population center of New York, on the scene of a notorious ash dump, one of the very great municipal parks of our country."

The Olympics plan - which backers say would, like the World's Fair, use an international event as a catalyst for major city improvements - includes joining the two now-contaminated lakes in Moses' Flushing Meadows-Corona Park into one big venue for rowing competitions. It would also build an Olympic Village in Queens, extend the #7 line westward, and create an 86,000-seat Olympic Stadium on the far West Side of Manhattan.

The Olympics bid garnered New York the U.S. nomination for the games, but the city must compete against a dozen cities around the world before the International Olympic Committee selects a winner in 2005. Meanwhile, city officials say that construction on some of the Olympics plans cannot wait until the committee makes its choice.

The Olympic stadium is just one component of the Bloomberg administration's plans for the West Side, including building green spaces, rezoning the garment district, and using bonuses to encourage high-rise development and new office buildings. Residents have said that a stadium -- which together with an expanded Jacob Javits Center would extend 11 city blocks -- and new business district could bring more traffic, cause rents to go up and displace residents and small businesses.

According to Hunter College professor Tom Angotti, Robert Moses would have been happy to see the new plans for Manhattan's far West Side, which "would basically bring an end to Hells Kitchen, the historic rough-and-tumble neighborhood... that's been depleted of its population over the last century, cut up by giant renewal projects." In an article for Gotham Gazette, Angotti imagined a conversation about the project with Moses, who he depicts as saying, "[The mayor] did it my way. Didn't listen to those people who live there. What do they know anyway? You have to think big and think about the future! You want to expand midtown to the west, just do it! How do you think we got Lincoln Center?"

Ron Shiffman, director of the Pratt Institute for Community and Environmental Development, said that it is too early to tell whether the Olympics plans will truly benefit the city or will become the newest example of using Moses' "meat ax" to decide a neighborhood's future. The Olympics could create projects that leave the city a valuable legacy, but, he said, "if they don't engage in a planning process with the people who live there, then the project could emerge into the kind of planning that Moses was engaged in."

Rebuilding Downtown

As planning continues on the city's other Moses-sized project, rebuilding Ground Zero, many details about the project are still being debated nearly two years after the attacks. They are being discussed by master plan architect Daniel Libeskind, World Trade Center site owner the Port Authority, lease-holder Larry Silverstein, state and city officials, family members, residents, and many others. At many points during the rebuilding process, people have asked: who exactly is in charge here?

"New Yorkers are asking if our city needs another Robert Moses," Alexander Garvin wrote in Topic Magazine. "It is an appropriate question: Despite his mistakes and his failures, nobody, not even Baron Haussmann in 19th Century Paris, has ever done more to improve a city," added Garvin, who until this spring worked as top planner for the head rebuilding agency, the Lower Manhattan Development Corporation, and also developed the plans for the 2012 Olympic bid. "In truth, Moses was not omnipotent, but rather an unusually gifted public servant who had mastered the Art of Getting Things Done. That art deserves attention more than ever."

Garvin wrote that the city should learn from Moses how to push forward with an agenda that many can agree on, how to compromise (as Moses did to build his Coliseum at Columbus Circle), and work for the kind of quality of design that Moses championed at Jones Beach. At the same time, Garvin wrote, any planning should make sure to include the public that Moses once sought to shut out of decisions.

But some involved in rebuilding say that it doesn't make sense to look back on the Moses method at all. Shiffman said that instead, New Yorkers should be proud of the distinctly non-Moses-like form that rebuilding the city has taken so far. "Given the fact that the World Trade Center site is controlled by the Port Authority and Larry Silverstein, it has been much more of a democratic process of planning than we have seen in a long time. Civic groups developed the framework and the standards by which the LMDC has to operate. And you can't forget July 15 of last year, when people turned down the original plans [at the Listening to the City town hall meeting]."

As Michael Kuo, a 9/11 victims' family member and a planner for the rebuilding project Imagine New York, said, "I think we are in a different era now."

* * * * * * * * * *

RELATED ARTICLE: A Community Plan for Moses’ â€Highway to Nowhere’

* * * * * * * * * *