Environmental Impact of Rebuilding Lower Manhattan

A new and possibly more contentious phase of the Lower Manhattan rebuilding effort is now beginning, as formal environmental reviews for key elements of the unprecedented reconstruction projects move into the spotlight.

In October, the Lower Manhattan Development Corporation is scheduled to release a draft environmental impact statement, covering its proposed plan for a memorial and for the redevelopment of the World Trade Center site. That document will trigger a formal period of public comment, as well as public hearings, that are likely to focus on key details of the redevelopment plan for the 16 acre site that had been home to the twin towers until they were destroyed in the terrorist attacks of September 11, 2001.

Meanwhile, the environmental review of a separate but related project -- the reconstruction and possible underground tunneling for West Street, which runs along the trade center's western edge -- is also expected to gain increased public scrutiny this fall.

As decision-makers begin their formal environmental reviews -- theoretically before making important design decisions about the redevelopment project and the adjacent roadway rebuilding -- the possibilities for conflict between environmental and civic groups on the one hand, and commercial interests on the other, seem increasingly likely.

WORLD TRADE CENTER MEMORIAL AND REDEVOPMENT PLAN

Public attention will of course continue to be centered on the planned memorial and redevelopment at the 16 acre World Trade Center site itself. The formal environmental review of this project is being coordinated by the Lower Manhattan Development Corporation, a subsidiary of the Empire State Development Corporation, although the Port Authority of New York and New Jersey, Governor George Pataki, Mayor Michael Bloomberg and others will play key behind-the-scenes roles.

The "proposed action" that is the subject of the forthcoming draft environmental impact statement includes a World Trade Center memorial and related improvements, up to 10 million square feet of office space, up to 1 million square feet of retail space, up to 1 million square feet of conference center and hotel facilities, as well as additional open space and cultural facilities.

Earlier this year, the Lower Manhattan Development Corporation outlined its planned review process, listing the 14 city, state, bi-state and federal permits or approvals that may be required for whatever project is ultimately built on the trade center site. And it summarized the topics that the environmental impact statement will discuss, including among other things expected impacts on open space and recreational facilities, neighborhood character, traffic, noise, air quality and waste disposal.

The environmental study will also identify adverse consequences from the proposed project, discuss alternatives to the proposed action and describe mitigation measures that could minimize environmental harm.

In accordance with state and federal environmental laws, this environmental study will be released in draft form and be the subject of a formal public review period. After that, the development corporation will respond to comments and possibly modify elements of the analysis and the project before issuing a final environmental impact statement, seeking permits and approvals for the project and beginning actual construction.

The final environmental review is projected to be completed, in an accelerated process, sometime early next year. Governor George Pataki has announced plans for groundbreaking ceremonies to take place in September 2004.

ISSUES OF PUBLIC CONCERN

The development agency received wide-ranging reaction to its plan. One major concern of environmental and civic advocates is that the environmental study as currently designed will not examine options that would reduce the amount of office space to be created at the trade center site. The proposed 10 million square feet of office space has been a cornerstone of leaseholder Larry A. Silverstein's plans for rebuilding.

"The program for office space and retail space should be developed in light of the total needs for office space and retail for Lower Manhattan,” representatives of the Civic Alliance wrote in its formal response, “not according to leaseholder obligations to rebuild an office complex that dates back to the 1960s and embodies assumptions about urban revitalization vintage to that era." The Civic Alliance recommended that the environmental impact statement “evaluate...options for significantly less amounts of office and retail, and greater amounts of cultural, civic and open space" at the 16 acre site.

Another concern, once the rebuilding is under way, is how solid waste from the redeveloped trade center site (and the rest of Lower Manhattan) will be managed, and where energy needed for the new development will be generated. Environmental justice advocates warn that the redevelopment project should not place additional environmental burdens on other city neighborhoods.

A good plan for Lower Manhattan means a plan that will not require the building of yet another power plant or solid waste management facility in a poor neighborhood in order to meet the greater demands, says Gail Suchman, an attorney at New York Lawyers For the Public Interest, who represents the Organization of Waterfront Neighborhoods and other community groups.

"We hope and expect that this new project will be a world-class model for green building and energy efficiency," says Ashok Gupta, energy expert at the Natural Resources Defense Council (where I work). Gupta and other advocates note that the development corporation’s plans promise that they will “consider” green building and sustainability principles in the environmental review. But energy specialists caution that unless a strong set of such design guidelines are incorporated into the draft environmental impact statement, the prospects for making this new development a show-case for energy-efficiency would dim considerably.

Environmental and civic groups are also urging that the environmental review analyze "truckless goods delivery" for the trade center site and study incentives to reduce traffic, encourage walking and reduce pollution in and around the site. Many of these organizations also remain concerned that environmental review for the trade center site explicitly take into account the separate environmental reviews being conducted for other closely-linked projects (e.g., the permanent PATH station , the Fulton Street transit center, the West Street reconstruction) to insure that these projects do not proceed in isolation and that the cumulative impacts of the combined projects are fully analyzed.

In response to these and other challenges, the staff of the Lower Manhattan Development Corporation remains optimistic.

"We were not surprised by the substantive points in the comments we received and we are going to explore alternatives that consider additional areas for commercial development outside of the 16 acre site," says LMDC Counsel Irene Cheng.

But the recent report that two insurance companies -- Allianz and AXA -- may block plans to demolish the damaged Deutsche Bank building, just south of the Trade Center site, could further complicate any proposal to disperse office and retail space beyond the 16 acres.

"As this is hardly a routine development project," the Bar Association’s Task Force the environmental review process should not be viewed as routine."

WEST STREET CONTROVERSY

On a different track, and outside of the public limelight, the New York State Department of Transportation is advancing a plan to reconstruct West Street (also known as route 9A) and to replace it with a covered tunnel that could cost up to $860 million.

At a recently held but little-publicized "public information" session, state transportation officials presented their plan for an underground bypass tunnel to be built -- during a five year construction period -- as a replacement for West Street. The only other option that would be considered by the transportation department in its environmental review process is a "no-build" alternative. Transportation officials suggested that the massive tunnel project would create a park-like setting above ground, provide more space for pedestrians and accommodate increased visitors.

But in contrast to the openness that environmental and civic groups believe the Lower Manhattan Development Corporation has displayed as that agency has advanced its redevelopment and memorial work, the State Department Of Transportation's environmental review plans for the West Street project have come under sharp criticism.

As things now stand, the state transportation department will conduct no public scoping process for its environmental review (since it claims only to be preparing a "supplemental" environmental impact statement to an eight year old environmental review document). The agency does not plan to study any low-scale alternatives to the tunnel project. Nor does the state believe it must even hold a public hearing when it releases its supplemental draft environmental impact statement next year.

Not surprisingly, public opposition is mounting. Local elected officials, including Representative Jerrold Nadler, Assemblymember Deborah Glick, and City Councilmember Alan Gerson, are expressing skepticism. And in a July 31st letter to State Transportation Commissioner Joseph Boardman, six transportation and environmental organizations -- Coalition to Save West Street, NYPIRG Straphangers' Campaign, Tri-State Transportation Campaign, Enviornmental Defense, NRDC and Tranportation Alternatives -- criticized both the process and the substance of the West Street reconstruction project.

Of course, the new State DOT plan for Route 9A is not the first time engineers have sought to address traffic issues along Manhattan's west side.

In the l930's master planner Robert Moses sought to advance his "West Side Improvement" project, including a five-mile expressway from the southern tip of Manhattan to 72nd Street. The story is recounted by Robert Caro is his award-winning biography of Robert Moses: "The Powerbroker."

"The West Side Improvement had two purposes," Mr.Caro writes: "to reclaim Manhattan's waterfront for its people, and to alleviate Manhattan's traffic congestion. It was to achieve these purposes that Robert Moses spent an incredibly large sum of money."

"But despite that expenditure -- all but inconceivable in terms of urban spending of that era -- the first of the two purposes was achieved only in part, " Mr.Caro concludes. "(I)nstead of reclaiming the waterfront for Manhattan's people, the West Side Improvement deprived them of it. And the second of the two purposes was not achieved at all."

With that history in mind, environmental and transportation groups are now gearing up for a fall campaign to secure a full-scale environmental review of the State Department of Transportation proposal for reconstructing West Street.

Eric Goldstein is co-director of the urban program at the Natural Resources Defense Council.

Studying How To Avoid Blackouts

New York's blackouts are legendary. In 1965, a single transmission line failed in Toronto, Canada setting off a domino effect that within 15 minutes left 30 million people from Staten Island to Ontario in darkness. A movie was made about it starring Doris Day.

New York's blackouts are legendary. In 1965, a single transmission line failed in Toronto, Canada setting off a domino effect that within 15 minutes left 30 million people from Staten Island to Ontario in darkness. A movie was made about it starring Doris Day.

Though steps were taken to prevent local outages from overloading the region's power grid again, another blackout occurred on a sweltering summer night in 1977, when a lightning storm short-circuited the city. It was the summer of the Son of Sam and an era of fiscal crisis. The blackout brought vandalism, violence and arson. According to the Blackout History Project, police arrested more than 3,700 people, but could not control rampaging mobs in some parts of the city. This blackout did not lead to a Doris Day movie.

It might surprise New Yorkers to learn that, a quarter century later, there are some 2,000 power-line failures a year in the city. Consumers do not notice most of them because New York's electric system, which industry rating groups say is the most reliable in the country, is designed so that if one power line fails, another picks up the slack.

Still, the problem of blackouts persists. In 1999, cables burned and overheated, casting a shroud of darkness over the Washington Heights and Inwood areas of Manhattan for 18 hours -- the largest prolonged blackout since 1977. In 2001, equipment failures led to scattered outages in Manhattan, Brooklyn, Queens, the Bronx and Westchester. And last summer, a fire at a Con Edison transformer cut electricity for seven hours to Manhattan's East Side.

A variety of things can cause power outages, including equipment failures, fires and weather conditions, such as lightning. The lights went out in Washington Heights on a day when electricity usage topped 11,850 megawatts, then a Con Edison record. And so conservation efforts can help avert power outages.

But cable failure played a major role in the Washington Heights power failure and has contributed to many problems that consumers never notice. With that in mind, Con Edison and other utilities that rely on underground cables want to learn how to prevent cable failures before they occur. That is why they have opened a laboratory in the Bronx to find out what makes seemingly good cables go bad.

THE ELECTRIC UNDERGROUND

Con Edison maintains some 126,000 miles of cables, about two thirds of which are underground and so fairly immune to lightning and other vagaries of the weather. High voltage transmission lines bring electricity from generators to local sub-stations. Medium voltage lines, called feeder cables, then distribute power to transformer boxes. From there, it is delivered by low-voltage lines to individual homes and offices.

The utility divides its service area into 78 networks, 33 of them in Manhattan. Each network contains from six to 24 feeder cables. One or two downed feeders within a network may go unnoticed, but if more fail it can overload the network and lead to outages.

Therefore, the best way to prevent outages is to identify vulnerable cables before they fail. "That's the Holy Grail," said Con Edison spokesman Chris Olert. "Knowing, 'Well, that cable is going to fail in eight hours or a week.'"

Even though utilities can be allowed to pass the costs of replaced cables on to ratepayers, they prefer to replace only those cables most likely to fail, rather than be forced to replace hundreds of miles of cable that could still provide years of services. And since consumers pay for new cables in the form of higher electric bills, they may endorse this conservative approach - unless their lights go out.

"We did testing on cable installed in the 1920s. We pulled it out, and it was as good as new," said George Murray, a cable engineer and the lab's acting director. "So, rather than replace a cable because of some arbitrary standard like age, we want to leave that cable in service and target cables about to fail or give us a problem."

But preventing outages is not the only reason to replace cables, says Jason K. Babbie, a policy analyst with the New York Public Interest Research Group. He says older cables tend to leak more power than newer ones and that upgrading cables would improve efficiency, save energy and alleviate the need to build more generators and sub-stations.

"While a cable from the 1920s may still be working that doesn't mean it's working efficiently," he said. "One of the criteria that Con Ed should be considering is how to improve the efficiency of the system as a whole."

Environmental benefits may also come from replacing older cables. Paper insulation in older cables contains oil that can leak into the ground in small amounts. Lead casing can also pose a risk. Newer cables are insulated with plastic.

Nevertheless, at the moment Con Ed's focus is on figuring out which are the cables about to give. According to Murray, small manufacturing differences in cables can affect how they perform under duress. A common cause of cable failure is what Con Edison engineers call "trauma," physical damage usually done by workers making repairs to the snarl of cables, pipes and fiber optic wiring that compete for space beneath the city's streets. (To view a cross-section of the city's underbelly, visit National Geographic's site)

Rock salt, used to clear streets of snow and ice, also can wreak havoc on cables. Salt is not only corrosive, but also conductive. This means that salty run-off after snowstorms can eat through insulation and carry current between conductors and to the ground. "The more salt in winter, the more failures we get in the spring," said Murray. As a result, there have been a particularly large number of failures this year although the public has noticed few if any of them.

MOCK MANHOLES AND AUTOPSIES FOR CABLES

The $10 million Cable &Splice Center for Excellence on Con Ed's Van Nest campus near the 180th Street subway stop in the Bronx is a joint project of Con Edison and the Electric Power Research Institute, a national energy research and development organization. At the heart of the new facility is a mock manhole encased in soil where the climate can be controlled to mimic conditions underground. The lab also includes four voltage-testing areas, a diagnostic lab and an impulse generator that can simulate the effects of lightning. The lab's total of three manholes enable engineers to study how moisture and other weather conditions can affect cable joints, which are typically found in manholes. Minus rats, cockroaches, water bugs, methane gas buildup, tree roots, garbage and so forth, the manholes are exact replicas of their underground counterparts, Murray said.

The lab is outfitted with an array of equipment painted in cheerful primary colors, including bright red transformers that can step up electricity to 120,000 volts -- three to ten times the charge that normally runs through the city's distribution lines.

"It's like an autopsy for cables. It's where cables go to die," said Olert.

Con Edison and its fellow utilities hope the lab's efforts will enable it to develop a diagnostic system to repair legacy cables more efficiently. "You have to look at a lot of different factors," said Walter Zinger an electrical engineer with the Electric Power Research Institute who is coordinating the lab's work with that of other partners in the institute's Cable Testing Network. "Say the normal failure probability is 'X' and in this condition it is '10X.' You still don't want to replace all those cables because the probability [of failure] is still one in 100 . . . And that's why we do this."

The lab's first task will be to research feeder cables of the kind blamed for the power outage in Washington Heights in 1999.

RELIABILITY AND EFFICIENCY

Capital spending by utilities has gone down in the past several years but reliability has improved, with Con Edison achieving the highest reliability index in the state.

A study (in pdf format) released by the New York State Energy Planning Board in 2000 found that New York City had a significantly lower rate of service interruptions per customer than the rest of the state. It also found that, although capital investments in the power transmission system declined dramatically from 1988 to 1998 (from $304.4 million in constant 1998 dollars to just $90 million), the reliability of the state's transmission system improved during the same period.

"This suggests that transmission system expenditures are being used more effectively, or that these factors have less of an impact on actual reliability than other factors," the report concluded. Spending on operations and maintenance remained constant during the period studied.

But failures still occur. Following the Washington Heights blackout, the state Public Service Commission issued a report calling on Con Edison to take a number of steps to prevent further outages and called for "accelerated replacement of older, paper wrapped feeder cables." Con Edison reportedly agreed to spend $2.4 billion over five years in capital improvements to its distribution system.

David Flanagan, director of public information for the commission said that since then, the utility has been keeping its commitments.

Some question, though, whether the system will continue to be reliable without some increase in spending. A spokesperson for Assemblymember Paul Tonko, chair of the energy committee, said Tonko believes the decline in capital spending and in replacing skilled utility workers could lead to problems down the road.

Danny Peralta lived in Washington Heights during the blackout in 1999 and remembers families sleeping in neighborhood parks to keep cool. He worries that Con Edison does not invest as much in neighborhoods like his as it does in other parts of the city. "There were parts of the city where the lights went back on. My neighborhood was one of the last to get light. It spoke volumes about the politics of the city," he said.

Con Ed says that failures may occur more frequently outside midtown and downtown Manhattan because the networks in the outlying areas cover greater distances. As a result there are more cables and connections between the local sub-stations and the homes and offices they serve and so a greater statistical probability that one will fail, Murray said.

In the longer term, research in cable technology could eventually save money. Tonko and others think that super conductivity cables, which are currently under development and can carry five times as much electricity as copper wires of the same size, might some day open New York's system to more distant suppliers and thereby encourage greater competition, bringing down electricity prices. "If you had super conductivity coming into New York City and Long Island, you would then have more capacity," Tonko said. "If you have greater capacity to deliver you open up the system."

It could be decades, though, before this technology is ready for general use. "As the Cable Center evolves, we may find new uses for its testing equipment," said Olert. But for now, the lab's research is focused on maintaining existing cables and keeping the city switched on.

Editor's Note: This article was first posted on our site on Monday, August 11, 2003 -- three days before the blackout of 2003.

RELATED ARTICLE: After The Blackout - Going Back To The Experts

Death of Seneca Village

Central Park at 150

.........................

Overview:

Still a Pioneer

Art in the Park:

Our Project for the Park by Christo and Jeanne-Claude

History:

» Birth of the Park

» Death of Seneca Village

My Backyard:

» Dancing in the Park

» An Escape from Reality

Crime:

Taking Back the Park from Crime

Reading:

Books About Central Park

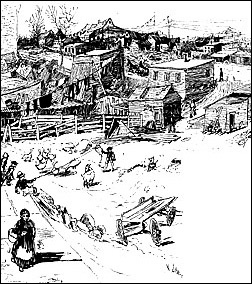

Turning Manhattan swampland into Central Park’s vast acres of woodlands, meadows and ponds took16 years and cost $14 million. But building Frederick Law Olmsted and Calvert Vaux’s “Greensward Plan” was not without a human cost as well. More than 1,600 people were displaced by Central Park, including Manhattan’s first known community of African-American property owners, Seneca Village.

From 1825 to 1857, Seneca Village was located between 82nd and 89th Streets at Seventh and Eighth Avenues. The New York State Census of 1855 reported that 264 people, largely African-Americans but also Irish and German immigrants, lived in Seneca Village. By the time it was destroyed, the village had grown to include three churches, a school and several cemeteries.

There are many theories about how Seneca Village got its name, according to the New York Historical Society: it could have been named for the Seneca tribe of Native Americans, or a distortion of the word “Senegal,” where many of the village’s residents may have come from. It also may have been a code word used by Underground Railroad fugitives, or named in homage to Roman philosopher Lucius Annaeus Seneca, whose book Seneca’s Morals was popular among African American activists.

The community was founded on September 27, 1825 when an African American former boot black named Andrew Williams bought six lots of land for $125, and another African American laborer, named Epiphany Davis, bought 12, for $578. The trustees of the African Methodist Episcopal Zion Church purchased six lots of land on the same day.

Buying property in Seneca Village was relatively inexpensive compared to prices downtown, and by 1850, African Americans in Seneca Village were 39 times more likely to own property than African Americans in other parts of the city. This made them more able to participate in civic life -- at the time, the New York State Constitution of 1821 required that African-American males had to own $250 in property in order to vote.

In 1853, the African Methodist Episcopal Zion Church built a church in Seneca Village, and, according to a newspaper account of the time, church officials laid a special cornerstone that contained a Bible, a hymn book, the rules of the church, copies of the New York Tribune and the New York Sun, and a letter with the names of the church’s five trustees.

The new church would not stand long enough for the cornerstone’s contents to become more than a few years old. The state legislature set aside the land for Central Park in the same year that the church was built. During the 1850s, newspaper articles described Seneca Village as “Nigger Village.” The New York Daily Times wrote on July 9, 1856, about Seneca villagers, “The policemen find it difficult to persuade them out of the idea which has possessed their simple minds, that the sole object of the authorities in making the Park is to procure their expulsion from the homes which they occupy.”

The government used the power of eminent domain to force the people of Seneca Village out of the area, giving them the final notice to leave in the summer of 1856. Those who owned property were compensated, but many fought to keep their land or get a better payment. The residents of Seneca Village did not re-establish their community in another place, and instead scattered throughout the city.

The story of the village that was destroyed to make way for New York City's great park went largely untold until recently, and it was not until 2001 that the Central Park Conservancy put a plaque commemorating the lost community in the park.