Poor Preparation, Confusion Lead Many to Fail GED Test

Some 1 million New Yorkers over the age of 16 do not have a high school diploma. For these people, the high school equivalency diploma -- the GED -- can offer the best hope of a better job or further education.

To get that diploma, though, these New Yorkers have to navigate an often confused and chaotic system. Most who try do not succeed. Only 47.5 percent of New Yorker City residents who take the GED pass it, compared with a passing rate of 56 percent for the state as a whole and a national rate of 71.5 percent. The state's rate is said to be the highest in the country.

To address this, adult education advocates and some members of the City Council would like to see the GED system get additional resources and become more centralized. The Paterson administration, though has proposed cutting the state program by $3.9 million budget or almost 30 percent. People who have studied the GED program say these cuts could extend the amount of time students must wait to take the test and reduce the state's already low pass rate even further.

GED Basics

The General Equivalency Diploma given by New York State is based on nationwide exam created by the American Council on Education. It can be taken by any New York resident 16 years old and older. Those between 16 and 19 have to meet tougher eligibility requirementsthan older people. In 2009, almost 29,000 individuals took the test in New York City, and almost 56,000 in New York state, according to the state education department.

The seven-hour test includes an essay and subtests in five subjects: writing, reading, social studies, science and mathematics. To pass, the test taker must score at least 410 points on each section -- on a scale, like the SAT, of 200 to 800 -- and average 450 across subjects for a total of 2,250 points. Students who take the test in French or Spanish also must pass an English proficiency test. Candidates may not take the exam more than three times in 12 months.

Contrary to popular perception, the GED is not easy. The American Council on Education sets the passing score at a point where only 60 percent of a sample of high school seniors would pass the test.

Beyond that, the certificate can indicate a student's determination, perseverance and valuable life experience. At the School of General Studies, Columbia University's school for "nontraditional students," the GED is a "necessary first step … indicating academic readiness," said Curtis Rodgers, the dean of admissions. But Rodgers said. "We also look at life experience -- what they did after leaving high school and coming to us -- that indicates personal preparedness for the career they are choosing."

The New York City Department of Education offers a range of GED programs, including separate programs for individuals under 21 and over 21. The City University of New York providescomprehensive programs on campus to help students transition to work or to college. GED programs in public libraries focus primarily on basic literacy. Community organizations also offer GED preparatory classes.

New York State subsidizes the GED program with $20 for each student who takes the test.

Slashing the Subsidy

Now, though, the Paterson administration, facing a massive budget deficit, has proposed eliminating that $20 payment. People involved in adult education say this could have a huge impact.

"If we lose this funding source we will have to suspend testing after June 30," said Mae Dick, director of the Adult Learning Center at La Guardia Community College. Even now, she said, "The monies generated by the $20 reimbursement don't come close to covering testing costs. If you test 1,500 people a year you get $30,000, which is the salary of one test site staff worker."

The state says it will continue to pay for materials and scoring the test.

One alternative would be to charge the students for the test. Every other state except Arkansas charges a fee ranging from $13 to $200, according to Jane Briggs, a spokesperson for the New York State Education Department. New York did away with its fee in 2008.

Denise Deagan, director of adult basic educationprograms at the Borough of Manhattan Community College, called the proposed budget "catastrophic" and said it would add six months to the already long waiting list for people hoping to take the test. This means, she said, that more students will fail since "students should test soon after they have attained readiness to maximize retention of the material."

Merryl Tisch, chancellor of the New York State Department of Education said advocates exaggerate the effects the cuts would have. "To focus on the $20 reimbursement per test taker budget cut is a simplistic view of the problem. It is one of three or four major problems," she said. "We can't fix any one problem without addressing the totality.

Tisch said, though, that the state education department has asked "the legislature to invest more money in the GED program so that we can get a comprehensive solution."

Taking the Test

"GED testing in NYC has become a barrier rather than a threshold to further opportunities," Jaccqueline Cook wrote in Our Chance for Change: A Four-Year Reform Initiative for GED Testing in New York City, a 2008 report prepared for the city Department of Youth and Community Development. "Simply stated, the NYC GED testing system functions poorly and is greatly underfunded."

Problems exist at many stages in the system, critics say. Dick of La Guardia Community College characterizes the current registration system for the GED test as "ridiculous." With no coordination among test sites, she said, students apply for five or six test seats to try to guarantee they get a place. According to Dick, the students are not notified if they do not get a seat. Often, an individual will take the test at one site and not bother to notify the other sites.

Since the $20 per seat provides needed funding for the test sites, test administrators have an incentive to overbook seats. "In order to get adequately funded for the exam, we book 170 people" for 100 places, Dick said.

In her 2010 State of the City speech, City Council Speaker Christine Quinn, who has termed the GED system "broken," called for making the city's job centers a hub for the GED. She also has proposed the creation of a website that would centralize test registration and help people find prep classes. Together, her change would cost about $1.4 million, according to the council.

Cook called for a $6.1 million to revamp the testing system. In its place, she proposed a citywide GED testing, scheduling and registration database that would track who has applied to take the GED, what seats are available and who has been accepted. In addition, Cook would establish a hotline for applicants who do not have access to computers, and a website with information about test content, procedures, methodology, strategies and scoring.

Quinn and other say that, before they can take the test, applicants should have to take a practice test. A predictor test, which is half the length of the official test, would familiarize the student with test content and multiple-choice format.

As for the test itself, Cook advocates breaking it up into shorter sitting periods. Currently, the test is administered in one seven-hour session or in back-to-back Friday evening and Saturday sessions. Students say sitting, let alone thinking, for that length of time is exhausting. And they say the 10-minute breaks between subtests don't even allow all 100 test takers to use the rest rooms.

Getting Ready

By many accounts, though, the problems with New York's GED program start long before the test. "What we are proposing for starters is to have New Yorkers complete a GED preparatory program before testing. This would correct New York's poor image of having a very low pass rate," Tisch said. "Other states in the nation do this. As things now stand in New York, anyone can sit for a test."

In their report for the Community Service Society, Lazar Treschan, and David Jason Fischer endorse Cook's recommendations but conclude that the problems New Yorkers face "begin earlier along the road, in test prep programs hampered by insufficient funding, ineffective teachers and inadequate oversight."

People seeking an appropriate GED instruction program must deal with a "baffling" and "frustrating" system, they said, and finding the right program is often a matter of luck.

Kennedy Fischer-Mack would probably agree. Soon after leaving high school at age 17 in 1989, Fischer-Mack took the GED test twice. But he said he never got his test results, and his GED instructors shrugged him off, saying they had no way of tracking the exam. "I got frustrated," he said. "The teachers just didn't care. For them it was just a job." So he gave up.

Today, Mack has his GED and is pursuing an associate degree in business administration at LaGuardia Community College. He enrolled in January soon after passing his GED and completing a college preparation program at LaGuardia. Why did he succeed this time? Teachers at LaGuardia "guide and encourage you every step along the way," Fischer-Mack said. "So, I never felt like giving up."

Treschan and Fischer also point out that there is no standard for the teaching of GED preparation courses and that even GED instructors who "do have state certification … are not necessarily prepared for teaching the GED." They recommend the state Education Department develop a graduate level course in GED instruction and cited a need for other trained staff, including guidance counselors, college advisors and social workers.

Since "nearly 20 percent of the city’s working age population has not earned a high school diploma or its equivalent," Treschan and Fischer said, "improving the current performance of the dismal GED system is an important priority."

Bloomberg Blames Albany for Fiscal Woes

Don’t blame me, Mayor Michael Bloomberg said on Thursday.

Blame Albany.

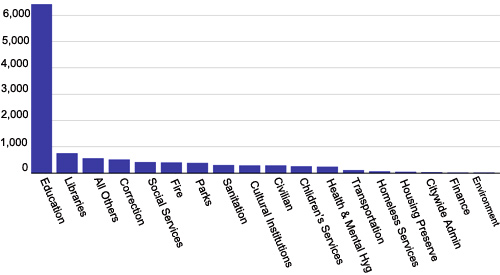

Figuratively shaking his finger due north, Bloomberg released a $62.9 billion budget proposal yesterday that would reduce the city's work force by nearly 11,000 people -- almost 7,000 of them from the Department of Education. The mayor shirked responsibility for the cuts, and instead took out the city's fiscal woes on Albany, which he contends could cut $1.3 billion in aid from the city.

"Make no mistake about it, unless the legislature acts New York City residents will pay the price for Albany's bad decisions," said Bloomberg, before delivering his annual PowerPoint presentation on the city budget. "And I will remind everybody who unfortunately may lose their jobs that it's because of Albany's fiscal irresponsibility for the last dozen years."

The state faces an approximately $9 billion deficit, and the legislature and governor have failed to reach an agreement on any plan to deal with it. The state budget was supposed to be approved by April 1. It is now 36 days late with no agreement in sight.

The state's failure to act, said Bloomberg, clouds the city's fiscal future with so much uncertainty that his administration had no choice but to plan for the worst. The city too faces a $5 billion budget hole, which the administration plans to close through cuts. His plan does not raise taxes.

It does propose to strip thousands of classrooms of teachers and close 20 fire companies and 50 senior centers. The mayor promised to hold the Police Department harmless in light of last week's attempted bombing in Times Square.

Cuts to the Classroom

By far, teachers will bear the brunt of the budget ax.

According to the mayor's budget proposal, about 4,419 teachers could be laid off. Another approximately 2,000 teachers could be lost from attrition. This scenario assumes, the mayor said, the city receives a $493 million cut from state education aid.

According to the Alliance for Quality Education, the State Senate's budget plan would eliminate $466 million from the city Department of Education, while the State Assembly's plan would cut $265 million.

That uncertainty is taking its toll in the classroom, said officials.

"We need to know what's going to be done here," said Schools Chancellor Joel Klein following the mayor's budget proposal yesterday. "There is an entire city of 1.1. million kids and their families who are out on the balance and we need guidance."

"You can't pay people with 'what ifs,'" said Klein.

Klein said the Department of Education would start the layoff process in June to make sure schools were prepared to open in the fall. Both Klein and the mayor would not confirm if the city would rehire teachers should they receive additional funding from Albany or from a federal jobs stimulus package targeting education. Reshuffling the classroom last minute could be disruptive, the mayor said.

In response to the cuts, education and labor advocates did not point their fingers at City Hall. They turned to the capital.

"The budget situation is a little brighter than it was in January," said United Federation of Teachers' President Mike Mulgrew in a statement. "But for the sake of the schools and the kids, the city has to join us in Albany in fighting for the revenues we need to prevent all teacher layoffs."

Officials in Albany don't see it that way. The state has tough choices to make too, New York State Budget Director Robert L. Megna said in a prepared statement.

"Mayor Bloomberg has repeatedly said that the state needs to make hard fiscal choices, and Gov. Paterson's proposed budget reflects exactly those kinds of hard choices," Megna said. "The mayor's budget uses the state as a scapegoat to shirk responsibility for their own budget choices."

Amputating Agencies

It's not just the Department of Education that is getting the ax.

In addition to closing 20 fire companies, the mayor proposed reducing the number of firefighters on 60 engines from five to four. About 68 percent of the city's fire companies already operate with four firefighters. In total, the Fire Department will lose 399 positions. The administration also proposed to start billing for false alarms if they occur at the same location more than three times in a six month period.

From the ladders to the stacks, the administration has proposed to cut the city's library workforce by 740 people.

On to the waves: The city hopes to save $300,000 by eliminating the Rockaway Ferry by the end of fiscal year 2010. It will reduce funding for the Queens and Prospect Park zoos, which will likely lead to an admission hike.

Social services, said advocates, have also taken a beating. The administration is still planning to consolidate 16 day care centers, mostly in affluent neighborhoods, and it plans on closing 50 senior centers.

"Once you close a center you can't reopen it," said Bobbie Sackman, the director of public policy at the Council of Senior Centers and Services. "We still think this is premature," Sackman said, urging the mayor to wait to see what Albany will come up with.

Meanwhile, four public pools could close and the swimming season could be reduced by two weeks under the mayor's proposal. Special needs housing for inmates on Rikers Island could also shutter. At the same time, the Department of Correction plans on generating $13.2 million by leasing unused inmate beds to federal agencies.

More than 4,100 after school spots are still on the chopping block, and caseloads at the Administration for Children's Services could increase from 9.5 to 10.9. The administration plans to shutter a drop-in homeless center in Manhattan and could eliminate 90 beds in shelters for homeless single adults.

The Department for Citywide Administrative Services hopes to discontinue the printing of the City Record, publishing it exclusively online, saving $665,000 a year by fiscal year 2012. The proposal would have to be approved in Albany.

If the Mayor's Office of Film, Theatre and Broadcasting has its way, filmmakers would have to pay $300 to get their applications processed, while the Department of Buildings plans on increasing fees for elevator applications.

All of this is subject to City Council approval before July 1. So far, some members aren't taking the proposals quietly.

Revenue on Wall Street

Just moments before the mayor released his executive budget, several members of the City Council gathered before the City Hall steps to demand action.

The council's new progressive caucus called on the mayor to consider taxing the city's most affluent, including implementing an earnings tax on hedge fund managers and increasing the personal income tax for the wealthiest New Yorkers.

"[The mayor] correctly points out that these are very difficult economic times, that unemployment is still high and that sacrifice is still necessary," said Councilmember Brad Lander. "Unfortunately, he is asking for all of that sacrifice to come from children and families and seniors and students in every neighborhood."

Bloomberg balked at any new tax on Wall Street or on wealthy New Yorkers, saying businesses could move elsewhere and the city would lose much needed revenue.

"At some point you drive them out," the mayor said. "We need jobs. We need people to stay here."

Other advocates and labor leaders hope the city -- and the state -- will turn to tax increases to stave off more layoffs and cuts.

"The city is embarking its way on cutting its way though the worst deficit and the worst fiscal times we've ever lived through," said Sackman. "And there is something fundamentally wrong with that."

Labor interests, like the Working Families Party, are also pushing for a tax on Wall Street bonuses. Billy Easton, the executive director of the Alliance for Quality Education, said a Wall Street banker's bonus tax could bring in between $3.5 to $7 billion in new revenue statewide. That, he said, could save the city's classrooms.

Budget Cuts Threaten Dozens of After-School Programs

A sixth-grade student at P.S. 150 in Sunnyside, Queens, Morgan Gelber relies on the after-school program until her parents get off of work. Without it Gelber said, "I'd probably be home alone for at least five hours."

Soon, though, Gelber and the 200 children in P.S. 150's after-school program in Sunnyside, Queens may have to make other arrangements. Under Mayor Michael Bloomberg's preliminary budget, the Department of Youth and Community Development will cut funding for Out-of-School Time, which provides after-school and summer activities for students, by $7.5 million. This would effectively close 33 free after-school programs as well as summer services at 30 middle schools. (For a list of the 33 programs slated to close go here.)

In total, the elimination of the after-school programs will affect roughly 4,000 elementary and middle school students in all five boroughs. Queens will take the biggest hit with 17 closing, followed by Brooklyn with nine.

A Sizable Cut

The preliminary budgetaddresses New York City's $4.9 billion deficit by calling for $1.6 billion of cuts to city agencies. The Department of Youth and Community Development will suffer one of the worst cuts. The mayor will announce the next step -- his executive budget -- on Thursday, which could make additional cuts or restore some programs. The City Council and the mayor must agree on a budget by July. The preliminary budget proposes that the Department of Youth and Community Development cut spending by 25 percent. If passed as is, the department's budget in the 2011 fiscal year will be $289 million, $99.1 million less then in 2010. The cuts could be worse if the state budget slashes $1.3 billion of aid to the city, as expected.

Department spokesman, Ryan Dodge, said the mayor's preliminary budget is likely to change between now and July. "Traditionally money is restored," he said, noting that last year the preliminary budget was $293.2 million, $96.4 million less then the $389.6 million final budget.

Closing Programs

Youth and community development selected the 33 elementary and middle school programs it would close based on two criteria: whether the program operates year-round and if it is located in what the department considers a high-need ZIP code.

But some school officials think the agency's calculus is off. "The claim is that we are not a high needs school, but I disagree," said Carmen Parache, principle at P.S. 150. "We have a high population of [English as second language] students, and parents need this stability. They can't afford to pay for after-school programs." Parache wondered why the program at P.S. 199, a school in the same neighborhood was spared.

Theresa Greenberg, an associate executive director of Sunnyside Community Services, which operates after-school programs in three schools, said programs could have been spared if cuts were made across-the-board, instead of focusing all the cuts in just some of the programs. "We would still have a piece of a program if they did that," she said.

A department spokesman, though, said across-the-board cuts would interfere with contractual obligations and "weaken the entire system of 421 programs and impact tens of thousands of children." After the cuts, it is estimated that after-school programs will serve 63,000 students in 2011, but programs could be overcrowded.

The Parents' Problem

Most of the concern over the proposed cuts has come from working parents. Soe Kyi, a nurse at Wyckoff Heights Medical Center, has two sons in the after-school program. "Sometime we work overtime, like 16 hours, and I have nobody to pick them up," she said.

Even parents who have a 9 to 5 job, need some place where for their children, said P.S. 150 program director Mirela Sujak. "Where are they gonna go for those three hours?" she asked.

According to the After-School Alliance, 25 percent of New York's children between kindergarten and 12th grade take care of themselves after-school. Students who would like to participate in an after-school program but cannot often lack transportation, a problem expected to become worse if the Metropolitan Transportation Authority cuts or eliminates student MetroCards.

Parents enrolled in colleges may need to drop out or place themselves on a slower track to a degree. Paola Ruiz, a teaching assistant with a daughter in the fourth grade, said, "When I first enrolled her here, I was going to school myself. It was comforting to know that she was here."

"In the worst cases, parents are going to quit their jobs or not continue their schooling because their kids don't have a safe place to go after-school," said Lucy Friedman, president of The After-School Corp., a non-profit advocacy organization. Friedman said she worries that the cuts will further widen the gap between students whose families can afford after-school programs and those who cannot.

Work and Play

The programs not only provide a safe place for students to go but offer recreational activities, cultural events, homework help and extra attention for students learning English as a second language. "Without after-school, my English wouldn’t be good enough," Lobsang Tsomo said before hiding her tears behind a sheet of paper. Basante Abuelmagt, who emigrated from Egypt, said. "This is my first year here in America, without after-school, I’d be at home getting bad grades."

Dileck Secilmis, a 24-year-old parent who teaches art part-time while attending York College, is one of the 27 staff members at P.S. 150 who help elementary students with homework and teach subjects ranging from dance, sports and karate to chess.

Standing in a classroom decorated with the colorful self-portraits of kindergarteners, Secilmis reads Harold and the Purple Crayon. Finishing the book she hands out purple crayons and asks, "What would you do if you were Harold?"

"I wanted them to use their imagination," she explains.

"We're facing a year where a sacred cow will be slaughtered,” said Brooklyn City Councilmember Lewis Fidler. "On a long list of every bad choice this will be almost the worst."

As chair of the Youth Services Committee, Fidler said he would work to secure funds for after-school programs when the budget comes before the City Council in June. He said, "I’m going to fight to make sure that we don’t destroy our future by hurting our children in the present."

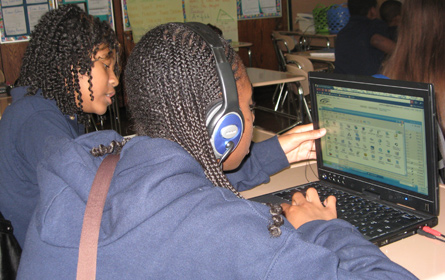

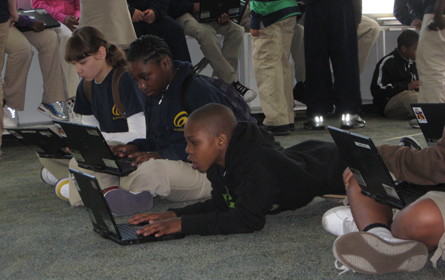

A Harlem Middle School Bets on Technology

Visit the common room of Global Technology Preparatory, a new middle school in Harlem, almost any morning of the week, and by 8:30 a.m., 15 minutes before the official start of school, you will find most of the school's 60 or so students, neatly dressed in blue and khaki uniforms. Some sprawl on the floor, some lounge in beanbag chairs, their laptops propped in their laps or on the floor. Groups of boys play DimensionM, a competitive math video game, while some check their e-mail. A small group of girls, noses in old-fashioned printed books, form a reading circle in one corner.

Attendance, the bane of many schools that, like Global Tech, serve a community of mostly poor minority kids, is not a problem here.

"Tabitha used to hate to go to school, now she loves it," said Maria Ortiz of her granddaughter Tabitha Colon who transferred out of a Catholic school to attend Global Tech. "We've had great experiences with every teacher," said Ortiz, adding that the school's focus on technology was a major draw for Tabitha.

As its name implies, this school relies on technology to capture the attention of its students, and to give them a sense of responsibility and empowerment as well as to teach academic subjects, such as math and English language arts, in new and more engaging ways.

With this approach, Global Tech is a poster child for one of New York City Schools Chancellor Joel Klein's latest experiments, the so-called Innovation Zone, or iZone. This effort seeks to use new approaches to education, including more flexible class schedules that extend learning throughout the day and calendar year, and digital technology to improve student engagement and performance. This school year, Global Tech is one of 10 pilot schools in the iZone, which will be expanded to 81 public schools in the 2010-2011 school year. The education department is hoping that Global Tech and other schools like it can finally do something to improve middle school achievement and solve one of the most intractable problems in the city's education system.

Across the Digital Divide

The majority of the student body at Global Tech is poor -- it is a universal Title I school -- and almost all are black or Latino. Only about half the kids have computers at home and even fewer have Internet access.

As it seeks to bridge the digital divide, the school has been using technology to "personalize" learning -- for example, using software and online instruction to offer multiple languages. Other technology allows teachers to identify, in real-time, how students are absorbing a lesson and to gauge when they need extra help or more challenging topics. A major goal is to let students work "at their own pace and allow them access and exposure to the world," rather than locking them away in the classroom, explained Julian Cohen, executive director of school innovation at the city Department of Education.

Using technology -- and the individualized education it affords -- Global Tech, one of the first two middle schools in the iZone, believes it can close the growing gap between what middle schools teach and what is required for success in high school. In 2009, less than 60 percent of middle-school students met or exceeded the English language arts standards; among eighth graders, only 71.3 percent met or exceeded math standards.

Chrystina Russell, the 29-year-old principal of Global Tech, is convinced that giving every child a laptop that bears his or her name will help provide students the differentiated instruction that they need and instill in them a sense of responsibility -- laptop "free time" is withheld when students misbehave -- as well as the conviction that they are both entitled to good schooling and capable of achieving, "just like suburban kids," she said.

The school's small size and technology infrastructure lets teachers more easily identify the strengths and weaknesses of individual students and prepare them -- academically, socially and psychologically --for high school and, eventually, college, according to Russell.

"Often the academic piece is there, but the responsibility piece is missing," explained Jackie Pryce-Harvey, 57, a special education teacher who helped Russell launch the school and plans to complete a certification program that will allow her to become Russell’s assistant principal. "By ninth grade, if you don’t know what's expected, it's too late; you can’t go to Bronx Science," she added.

So far the plan seems to be working. The students treat their Dell tablets with care, and there have been virtually no accidents or vandalism. Russell, who worked as a special education teacher before becoming a principal, had hoped to let the students take their computers home, but the education department vetoed the idea. Parents objected, worried that the computers would make their children, many of whom live in unsafe neighborhoods, targets of violence.

The students are expected to develop a digital portfolio of their work, which they will submit with their high-school applications. "Kids, when they leave eighth grade with their portfolios, will already be thinking about college," said Russell. These kids, many of whom feel "beaten down" by poverty, the loss of a parent and sometimes both will be "confident about who they are," she said.

The technology clearly is a hook for many of the kids. Stephanie Davis, one of several parents who transferred their children out of charter schools to attend Global Tech, said "The technology -- it's another way to really keep him focused; my son is learning a lot. I walk around every day bragging about this school."

The students just took their first standardized test, so scores are not yet available. But by most measures, Global Tech appears to be doing well. Inside Schools.org lists attendance at the school, which opened its doors last fall with three sixth-grade classes, at 95 percent. A review of the individual attendance records shows that attendance has improved, for most individual students, by a factor of two or three from what it was when they were fifth graders at other schools. Nor has Global Tech lost more than handful of students since the start of the school year -- a common problem for many schools in poor inner-city neighborhoods.

Paying the Bills

For schools in a cash-strapped system like New York City's, a technology-oriented curriculum presents daunting funding challenges. In addition to having to provide, and maintain, devices from smart-boards to computers and video cameras, Global Tech needed help integrating technology into the curriculum and training its teachers. Pryce-Harvey, did not even use email when she and Russell met as New York City Teaching Fellows five years ago. But with the help of an education department specialist funded by Cisco, she has been willing to start experimenting in her classrooms with video and PowerPoint presentations.

Much of the school's technology and support infrastructure has come from corporate donations and grant-funded programs, most of it funneled through the Fund for Public Schools, an organization that supports school-reform efforts. Russell considers fund-raising a necessary part of her job and has assiduously cultivated private backers, such as Lazard Ltd., an investment bank, and Cisco, which has worked closely with the education department on its iZone strategy. "Sustainability is the one thing that keeps me up at night," she said.

Math and Maps

Another key challenge is integrating technology with creative approaches to instruction. The way technology is used in schools like Global Tech dramatically changes not only how education is delivered by teachers and received by students but also the boundaries that traditionally have separated the classroom from the outside world.

At the most basic level, a wired classroom can help good teachers do a better job, and keep kids who have grown up as part of the Internet generation, engaged. Take David Baiz's math classes, which use a combination of animated software, computer-aided assessments, math video games and traditional pen-and-paper calculations to teach geometry. Baiz has a software program called Geometer's Sketchpad that animates geometric shapes, showing rotations, dilations and reflections.

"The visual stuff is much easier to teach using such software," said Baiz who doubles as the school's tech guru. While Baiz believes that kids have to learn basic computation skills, he said, "The technology is more engaging -- it provides more manipulations, more visuals, more critical thinking."

Several times during the course of a lesson, Baiz conducts a quick assessment. He projects math problems on the smart board. The students, using clickers, select the right answer from a multiple-choice list; their answers register on Baiz's laptop so he can see instantly which kids are having trouble grasping a concept.

Anecdotal evidence suggests that Baiz's wired math classes are working. For one thing, math games have become a favorite competitive sport at Global Tech.

In March, Derek Ortiz, a Global Tech special-education student, was the only child from a Manhattan public school to qualify for the DimensionM competition that tests students for speed and accuracy. Derek was one of 12 students to qualify for the middle school individual competition, held at Columbia University in March. Despite being one of the youngest competitors in a pool of mostly seventh and eighth graders, Derek, a sixth grader, came in tenth. That has inspired his friends at Global Tech to try to qualify next year.

Weaker math students also are excelling. For example, Tabitha Colon, who struggled with math since kindergarten, has finally reached grade level in math, and her grandmother Maria Ortiz credits Baiz's class.

How much of this is Baiz's teaching style and how much is it the technology? "I’m getting better as a teacher," said Baiz, 27, with a wry smile. "But not that much better."

In social studies, Global Tech uses online mapping technologies, such as Mapquest and Google Earth to teach kids both geography and about their local neighborhood. The students learned latitude and longitude, how to read maps, cardinal directions and compass skills. They can also take virtual walking tours of other cities. As a final project, all the children produced "urban orienteering" PowerPoint and video presentations, which will go into their portfolios.

Redefining School

Technology also is pushing the physical boundaries of the classroom and allowing the school to offer more with limited resources. Valerie Miller, the school's Spanish teacher speaks no other foreign language but supervises a classroom of students who are taking any one of four languages -- Spanish, French, German or Mandarin/Chinese. Wearing headphones, each student works at a computer terminal using Powerspeak, a foreign-language software program.

Occasionally, the students receive live instruction from a Powerspeak teacher elsewhere in the country who interacts with the student via voice -- the kids wear headphones -- as well as via live chat on their computers and on a smart board.

The distance learning demonstrates both the promise and the obstacles that New York City public schools face in embracing these technologies. Russell notes that some of the remote instructors, most of whom are used to teaching kids from more affluent neighborhoods, have used "inappropriate" harsh criticism of her students, many of whom are studying a foreign language for the first time.

"I have no problem with high standards," said Russell. "But some of these instructors don't understand the extra scaffolding that our students need."

Under current New York State rules, every class must be supervised by a certified teacher. Russell and principal's at other iZone schools are already thinking about -- and in some cases experimenting with -- remote learning. Any extension of this would almost certainly require a major change in the relatively rigid work-rules now in teachers' contracts.

Choosing a Staff

Many public school teachers put in extra work on behalf of their students. But implicit in the iZone initiative is the idea that teachers will be available, if not 24/7, then much more frequently than the contract requires. Many of the teachers at Global Tech make themselves available to students via email after hours and on weekends.

"I can email teachers; they're always on line to get emails from kids who might need help," said Jenny Lee Cruz, a sixth grader who said she recently got the power point notes for a social studies project, as well as other assignments, online when she was home sick.

Since Global Tech is a new school, Russell had the luxury of handpicking her staff. Four of the school’s half-dozen full-time teachers, Baiz, Jhonary Bridgemohan, who teaches English language arts, and Courtney Lee, the science teacher, worked at CS 4 in the South Bronx with Pryce-Harvey. In fact, throughout last spring and summer, before the teachers were officially hired, Russell and Pryce-Harvey hosted brunch many Sundays at Pryce-Harvey's Harlem brownstone. Over gourmet meals prepared by Pryce-Harvey, who hails from Jamaica and moonlights as a private chef in the Hamptons during the summers, the prospective staffers gathered without a job guarantee, to plan curriculum, strategize ways to recruit kids and define criteria for new hires.

The Sunday brunches underscored the collaboration and flexibility that Russell expects from her staff -- and that she insists is crucial to a successful school -- as well as an explicit understanding that their teaching responsibilities do not end when school officially lets out at 3:30.

Global Tech also has benefitted from the subtler advantages that come from being part of one of the chancellor's pet projects. It was allocated space in an exceptionally sunny modern building with picture windows that was especially outfitted with new overhead lights, refurbished bathrooms and wireless internet access by one of Eva Moskowitz's Harlem Success Academy charter schools. Just before the charter school moved out, Moskowitz donated two of its smart boards to Global Tech, which shares the building with PS 7.

The Challenges Ahead

As Global Tech reaches the end of its first year, it faces continuing funding challenges as well as the pressures that come with much larger size and expanded promgramming. Positive word-of-mouth has led to a surge in applications; as of April, close to 300 students had applied for the school's incoming sixth-grade class. Russell, who scrambled to recruit her first students last summer, now hopes the education department will cap the incoming sixth grade class at 93. "Otherwise it’s really not a small school anymore," she said.

After several months in which budget cuts threatened the funding to purchase laptops for next year's sixth graders, in late March, Russell got word that the education department will provide $100,000 in funding for each iZone school.

The school also has just been selected by Citizen Schools, a not-for profit after-school learning program, for a partnership that will extend Global Tech's school day to 6 p.m. Students will get homework help and academic enrichment and participate in hands-on apprenticeship programs taught by Citizen Schools teachers and volunteers.

In March, Global Tech hosted Computers for Youth, a program that provides free desktop computers, loaded with educational software, and training for underprivileged young people. The program is actually designed to teach parents how to help their children with schoolwork. Almost all the school's parents signed up for the program and, following three hours of training that began at 7:30 a.m. on a cold, wet Saturday, the families, pulling metal grocery carts, hauled their desktops, bundled in plastic, home through a torrential downpour.

The desktops will help give this year's sixth-graders the tech support they need at home. But funding technology clearly will be an ongoing worry. New families, new teachers -- the school will have to hire at least six more for the next school year year in addition to at least a half dozen relatively inexperienced teachers from Citizen Schools -- and more visibility also will test the school's ability to adapt itsvision to a larger school and to serve as a model the Department of Education can use to improve middle schools throughout the city.

Andrea Gabor is a professor of Journalism at Baruch College/CUNY and the author of several books, most recently The Capitalist Philosophers (Three Rivers Press, 2000).

Helping All Students Get a Meaningful Diploma

New York City's on-time high school graduation rate reached 59 percent for the class of 2009, and according to the New York Times, as Mayor Michael Bloomberg announced the newslast week he said it should get all New Yorkers smiling.

It's certainly a better statistic than the 46.5 percent on-time graduation rate in 2005. The latest figures show that groups with traditionally low rates have also improved: Students with disabilities have gone from a 17.1 percent rate in 2005 to 24.7 percent, and English language learners have increased from 26.5 percent to 39.7 percent.

But can the rates continue to go up -- or even stay where they are now? Graduation requirements are in the process of getting tougher, and this could reverse the trend toward higher graduation rates, particularly for English language learners, called ELLs by the Department of Education.

Many educators, including Schools Chancellor Joel Klein, welcome the change. Noting the high percentage of New York high school graduates who need remedial classes in college, they say more-demanding graduation standards should make students better prepared for further education. But New York State United Teachers, the union for teachers throughout the state, worries that tougher requirements will increase dropout rates.

Both sides make a valid point.

A Single Diploma

For many years, New York City’s public high schools awarded two basic kinds of diplomas. Students with scores of at least 65 percent on five Regents exams have received a Regents diploma; those who score at least 55 percent on all five tests have received a local diploma.

The state Board of Regents is now phasing out the local diploma on the grounds that it is insufficiently rigorous. In the class of 2009, students needed scores of 65 or higher on at least two of five Regents exams; by June 2012 they will need scores of at least 65 on all five tests.

The stricter requirements may have a particularly hard impact on English language learners, as they must take the same English Language Arts Exam that native speakers do. English language learners are allowed to take their other Regents exams in their native language, so reaching the score of 65 on the other four exams may not be such an onerous task.

I teach English as a Second Language at Bronx Community College, and many of my students are graduates of the New York City public schools. Often these students lack basic reading and writing skills in English even when they have been in New York schools since ninth grade. This makes me sympathetic to those who want higher standards. At the same time, I wonder how the public high schools will keep older immigrant students in school and get them through the Regents exams.

This concern is shared by the New York Coalition for Educational Justice, which last year issued a report on the implications of the new graduation requirements, titled Looming Crisis or Historic Opportunity? The report claims, "Unless the New York City Department of Education seizes this moment of opportunity to strengthen teaching and learning … additional thousands of the school system's high school students will be threatened with the failure to graduate."

The report also notes that in the class of 2007, only 11 percent of all English language earners graduated on time with a Regents diploma. (The numbers just released for the class of 2009 do not show how many English language learners graduated with Regents diplomas.)

One member of the class of 2007 was Wilton Guerrero, an English language learner who received a local diploma after just eight months in the United States. His story illustrates the local diploma's inadequacies. Yet it also raises serious questions about how schools will help immigrant students with limited English meet the new graduation requirements.

A Rush to Graduate

In November 2006, Wilton enrolled at John F. Kennedy High School in the Bronx. He was 18 years old, had just immigrated from the Dominican Republic and knew almost no English. Although high school credits transferred from his native country qualified him for 12th grade, he would still need to pass five Regents exams by June 2007 if he was to graduate at the end of the school year. And while he could take four of the exams in Spanish, he would have to take the English Language Arts Exam designed for native English speakers.

The math Regents was no problem. Wilton passed the Spanish version of the test shortly after he enrolled in Kennedy. As a result, school administrators told him he wouldn't need any math instruction. This freed up time for the many other classes he needed.

Wilton threw himself into an academic whirlwind so he could get his diploma with his 12th grade class. He took 14 classes a day, beginning at 8:20 a.m. and finishing at 7:30 p.m. The evening classes were with students in a special program for older students; the day classes were at his high school.

In June 2007, Wilton fulfilled his goal. He earned all the credits he needed and passed all five Regents exams, including English Language Arts. His English Regents score, however, was just 56 percent, one point over the minimum needed to pass.

When he received his diploma, Wilton could conduct basic conversations and transactions in English. But his English was far from fluent. He could not write an essay without numerous grammatical errors or read college-level texts. And since he had never studied math in English, he didn't know any English math vocabulary.

Wilton worked extraordinarily hard during his short time at Kennedy. But should he have graduated when he did? Under the tougher standards that will be fully in place by 2012, Wilton's 56 on the English Regents would have prevented him from graduating.

Now a student at CUNY's Bronx Community College, Wilton believes he should have stayed in high school until his English improved. He points out that in fall 2007, he failed all three CUNY basic skills tests in reading, writing and math.

"I knew how to do most of the math but I didn't understand the words in the problems," he remembers. "Also it had been more than a year since I’d taken math, so some things I forgot. On the reading test, I knew some of the words but not enough to understand the passages. On the writing, I was completely lost about what I was supposed to do."

After getting his test results, Wilton enrolled in the CUNY Language Immersion Program, an intensive non-credit English program that provides college-bound immigrant students with 25 hours of instruction per week. At the same time, he took a Saturday class to prepare for the CUNY math test. One year later he had passed the CUNY tests and was ready for credit-bearing classes at Bronx Community.

If the local diploma had not been an option, Wilton would have been able to stay in high school longer. As a result, his reading and writing skills might have improved to the point where he wouldn't have needed to pay for non-credit classes to prepare for college. In fact Wilton's brother Pablo, who is a year younger, did stay in high school one year longer than Wilton, and was able to go straight from Kennedy into credit-bearing classes at City College.

Racing the Calendar

For the Department of Education's purposes, though, it was probably better that Wilton graduated when he did. In reporting graduation rates, the city emphasizes the percent of students who graduate on time and makes no allowances for 12th graders who begin the school year with no English.

Schools with low on-time graduation rates face penalties. Last month the Department of Education finalized plans to shutter 19 schools, mostly high schools where fewer than half the students graduate on time with any type of diploma.

These closures may make other schools reluctant to admit older immigrant students, who are unlikely to qualify for Regents diplomas fast enough to land in the "on-time" graduate category. While schools cannot legally turn away students who are under 21, school administrators can encourage them to enroll in high school equivalency GED programs instead. School administrators could feel pressured to do this if they know that low on-time graduation rates will target their schools for elimination. GED programs are often less academically rigorous than regular high schools.

Needed: A More Comprehensive Approach

A high school diploma does not signify much if it's given to students who lack basic skills. But educational administrators won't improve the situation for future Wiltons merely by mandating higher Regents scores. They need to re-assess their whole approach to older immigrant students, particularly those with college aspirations.

Wilton says his English classes at Kennedy focused mostly on basic communication, not on developing the reading and writing skills he would need in college. According to David Loo, who teaches English as a Second Language at Manhattan Comprehensive Night and Day High School, the education department "has failed to provide adequate training and curriculum for ESL teachers preparing students for the English Regents." At his public school, Loo says, the assistant principal for English and ESL found funds to pay him and a colleague to design a new curriculum to prepare English language learners for the tougher graduation requirements.

This type of effort needs to take place on a citywide basis. Math skills need attention as well. English language learners should continue taking math classes even if they pass the math Regents, as unused math skills quickly atrophy. And even English language learners with strong math skills need to be taught English math vocabulary.

The Department of Education should also recognize that non-English speaking students who arrive in 11th or 12th grade will need more time than native speakers to reach academic proficiency. For this reason, it should redefine what constitutes "on-time" graduation for these students. Interestingly, State Education Commissioner David Steiner seems to agree. When the new graduation figures came out, he told the Times, "We need to encourage kids to stay in school a fifth year if they need it."

The end of the local diploma could help immigrant students reach higher standards. But the jury is still out on whether the new state policies will help or hinder these students once the stricter graduation rules go into effect.

Ellen Balleisen teaches English as a Second Language in the CUNY Language Immersion Program at Bronx Community College,

Charter Schools Enter Uncharted Waters

This article originally had the incorrect day for the Panel on Educational Policy's vote on use of school space. The meeting is Wednesday, Feb. 24.

They stood under the scaffolding outside PS 188, the Island School, separated by a narrow walkway and strongly held viewpoints. One group wore orange shirts and carried matching signs in support of the Department of Education's plan to give Girls Preparatory Charter, an elementary school planning to expand into the middle grades, more room in the building. Facing them were parents, students and teachers from PS 188 and PS 94, the other two schools in the facility. They said giving Girls Prep additional space will squeeze the low-income and local kids at PS 188 as well as PS 94's autistic students.

This rivalry on the Lower East Side represents one skirmish in a fight that has raged across the city -- from Harlem to Cypress Hills -- as the Department of Education attempts to carve out places in its buildings for charters schools.

In some ways, this fight is the classic New York struggle over space. But it goes beyond that.

Years after charter schools established themselves as part of the city's education mix, New York City and state now find themselves in the midst of a bitter fight over the role of the privately run, publicly funded schools. Supporters, including the Bloomberg and Obama administrations, point to the success of charters. They say the schools can provide parents with more choice, particularly in lower income communities where families have had few options. The fight against them, some charter supporters say, has more to do with protecting the teacher's union than with educating children.

Other parents and politicians, along with many teachers, fear that the Bloomberg administration wants to turn the public school system over to private operators who will ignore the neediest children in the system. Rather than setting up privately run alternatives to regular schools, these critics say, the Department of Education should concentrate on improving the schools we already have.

Approaching 200

The first charter school opened in Minnesota in 1992. But with unions leery of the proposal (even though United Federation of Teachers President Albert Shanker was an early supporter), New York did not allow charter schools until 1998, when former Gov. George Pataki, a strong proponent, tied the issue to a pay raise for the legislature.

As of September, there were 99 charter schools in New York City. They serve less than 5 percent of public school students, more than 32,000 children, mostly in the elementary grades. Mayor Michael Bloomberg and his Schools Chancellor Joel Klein envision doubling the number of charters in the city to 200 schools accommodating for 10 percent of city students --more than 100,000 kids.

Charters must be approved by the State University of New York, the state Department of Regents or the city Department of Education and must comply with a number of rules -- for example, they have to select students by lottery not, say, by competitive exam. While charters set their own curriculum, their students do take state tests. The schools also make their own decisions about hiring and firing and do not have to use Department of Education contractors. Although they can have unions, most do not.

While charters receive a per pupil allocation from the government -- based on per pupil costs in regular public schools -- many spend far more than that thanks to the fruit of outside fundraising. For example, the Eli and Edythe Broad Foundation, according to BusinessWeek, donated $18 million to the Knowledge is Power Program, which operates six schools in New York. This along with freedom from many Department of Education requirements help schools offer smaller class sizes and longer schools days.

Since the state law does not provide charters with money to build facilities, Klein and Bloomberg have opened space in school buildings to them. By one count, about two thirds of the city's charter schools are located in Department of Education buildings.

At its meeting on Wednesday, Feb. 24, the Panel for Educational Policy is set to approve about a dozen space allocations involving charter schools. These include placing Lefferts Gardens Charter School in PS 92 in Brooklyn, putting a Bronx outpost of former Councilmember Eva Moskowitz's Harlem Success Academy in PS 146 and having IS 302 in East New York share its space with a new Achievement First charter.

Despite crowding in some city schools, buildings overall are about 80 percent full, the Department of Education says. This means that many -- including PS 188 in the Lower East Side -- have available classrooms, according to the department. But what city officials at Tweed see as underutilized areas, parents and teachers see precious space for small group work, science experiments, rehearsals or computer labs. Their schools, they say, will lose these facilities if they have to share space with another school.

Lenore Brown, whose grown son attended IS 302, which is set to share space with a new elementary charter next year, said the school had been overcrowded, until the education department moved another school out. The staff at 302 now uses the extra space for small group instruction.

In addition Brown said, "Our school is developing a performing and acting program." That, she said has contributed to an overall improvement, so that "children in the neighborhood are looking forward to going to IS 302 because of the progress."

Discussing the department's attitude, Brown said, "To me, it seems whatever works, they try to break."

The charter parents see their children's fortunes at stake as well. Hilda Salazar, whose daughter attends Girls Prep, had older children in public and parochial schools and sees charter schools -- particularly Girls Prep -- as a far better alternative.

"It's not only academics" she said. "It's values. It's morals. It's things you need for life."

Salazar wants her daughter to be able to attend a Girls Prep Middle School and is irate over criticism of the school's expansion. "The UFT is behind it all,'' she said.

An Atmosphere of Distrust

Suspicions run high. Jacqueline Ancess, the principal at Manhattan East Side School for Arts and Academies, wrote to parents alerting them that the school is threatened by backroom maneuvering that could evict the arts school to make way for a charter.

"In a secret deal between Moskowitz and the DOE … the stage has been set to evict the school from the home it has been in for over 15 years. … This is only one instance of an attack on a public school system by the very people who should be protecting it," Ancess wrote.

The battle over the allocation of space is echoed in the fight over school closings. Last month, the Department of Education, despite pleas from parents, student and teachers, decided to phase out19 schools. Many opponents say the closings are part of a general attempt by the Department of Education to squeeze out the city's neediest and most at risk students and pave the way for more charters.

"Parents are legitimately angry about schools being closed," said James Merriman, chief executive officer of the New York Charter School Center, but the explanation being put forward by opponents, he said, "is a narrative that the UFT is interested in."

"The city is making some necessary changes and ruffling a lot of feathers," said Steven Evangelista, co-director for operations at the Harlem Link Charter School.

Teachers union President Michael Mulgrew has said the union is not necessarily against charters. But at a rally in Harlem last month, he said creating charters and small schools "is not supposed to be about putting one school against the other, one parent against the other." (The UFT's press office did not return calls for this story.)

The Charter Cap

Space is just one issue. If the city creates more charters, it needs a change from Albany. Current state law allows a maximum of 200 charter schools. Prompted by the federal government's Race to the Top Fund, which rewards school systems that encourage charters, Gov. David Paterson earlier this year sought to raise, if not eliminate, the cap.

The legislature responded by setting a number of conditions, including a requirement that the community approve the placement of a charter in an existing school building. Bloomberg, for one, viewed the Senate proposal as "poison pill." In the end, neither Paterson's proposal nor the legislature's alternative passed, and the charter cap remains stuck at 200.

"This bill, masquerading as a charter cap lift, instead would have shackled chartering beyond recognition," Peter Murphy of the New York Charter Schools Associationhas said. "The teachers union narrowly missed terminating charters, practically speaking."

Assembly Speaker Sheldon Silver tied the rejection of Paterson's proposal directly to the fight over space. "People who were supporters of charters previously have become anti-charter as a result of their experiences," he told the Times.

Having lost their bid to raise the cap, charter school supporters have now geared up to fight what they see as a disproportionate cut in state education aid.

Power Plays

Merriman of the New York Charter School Center, which helps charters get started, said the opposition to charters has arisen precisely because the movement has strengthened its position.

For years he said, unions and others "thought we would remain on the margins." Now, he said, New York "has a charter movement that works and is a model and the envy of other people." If charters continue to expand, Merriman said, many students would attend schools where the teachers and staff do not belong to a union. "That political threat is what's at work here. Unions looked and said, 'That's a prospect we don’t like,'" Merriman said.

But State Sen. Bill Perkins, who has opposed the cap, sees it differently. Charters, he said at a recent panel, "have not been accountable in terms of the success they are achieving and in delivering services to all children."

While only a small percentage of city kids go to charter schools, they play a larger role in some communities, notably Harlem. A recent count of the 29 Manhattan charter schools, placed 24 north of 96th Street. The concentration of charters in black and Latino areas of the city, Perkins has said, creates a system that is "separate and unequal."

Many parents in Harlem and other poor communities counter that it is the conventional public schools that have created a separate and unequal system. "Unfortunately," charter school parent Daniel Clark Sr. said at the panel, "where there are parents of color and kids of color, the schools are failing, district schools."

Merriman agrees. Charters, he said, "are working and parents want them."

Whose Research?

Statistics prove charter schools do better, say the Department of Education and charter school backers. A study by Caroline Hoxby, a Stanford University economist, found New York students who went to charters from kindergarten through eighth grade did almost as well on the eighth grade math test as their counterparts in suburbia, nearly eliminating the so-called achievement gap.

Another recent Stanford study, this one by Margaret Raymond, found that over a three-year period city charter school students did four points better on standardized reading tests than similar kids who did not attend charters and 15 points better on the math test.

In an article in the Los Angeles Times, Raymond said not all charter schools in the country show these kinds of results. But, she continued, "charter schools as a whole [were] better in New York than in any other city we have studied." She credited this to the strong support for charters, the organization that can guide new schools and "high quality oversight."

Diane Ravitch, an education historian frequently critical of the Bloomberg administration has cited another reason: Many charters in New York "have wealthy sponsors who donate millions of dollars to their schools. This helps them to have smaller classes and more resources than the local public schools."

While the numbers look good on the surface, critics, notably the United Federation of Teachers, have taken aim at these claims. They say charters do not represent a true cross section of New York students, neglecting, in particular, children who do not speak English, are homeless or require special education. The union's recent study, Separate and Unequal, found that while 14.2 percent of city students are English language learners, only 3.8 percent of charter students are.

Private Operators

Regardless of the results, the very idea of private organizations and companies, however well intentioned, makes some people uneasy.

"Stop the mayor, the public school slayer," opponents of school closings chanted at a rally outside Bloomberg's East Side home last month.

Take the statement of Seth Andrew, founder of Democracy Prep, a charter in Harlem, as he argued for raising the charter cap. "What the legislature hasn’t seemed to understand," he said to the Times, "is that the best charter operators in the country are mobile, and when they do harmful things to charters, the best operators move to more supportive environments."

Traditional public schools have to serve all kids, charter critics say, while charters do not. At the meeting on school closings last month, a representative of State Sen. John Sampson warned, "Charter schools are coming in and the people that go to these [closing schools] cannot enter the charter schools for whatever reason."

Another person declared, "Bloomberg is in a race to put as many charter schools as possible in our schools because it’s all about the money."

Critics point to the several hundred thousand dollar a year salaries paid to some charter executives, such as Moskowitz and Geoffrey Canada of Harlem Children's Zone. And they see opportunities for cronyism and favoritism.

Canada of the Children's Zone has had close ties to the mayor. On one hand, he supported the overturning of term limits and the continuation of mayoral control -- and lobbied hard for both. Canada meanwhile has reaped hundreds of thousands in city contracts as well as in personal contributions from the mayor.

Earlier this month the Daily News reported that Canada's Harlem Promise Academy is one of three politically connected charters that will get city capital funding.

Another school slated to receive funding -- PAVE Academy in Brooklyn -- is run by the son of a man who has given millions to Bloomberg's educational charities.

Then there is the case of the New York City Charter High School for Architecture, Engineering and Construction Industries. The city plans to put the school in what has been Alfred E. Smith High School in the Bronx, closing down all but one its vocational programs. The department cites Smith's low graduation rate and mediocre performance. But according to reports in both the Times and the Daily News, the charter has many problems of its own. Its founder and a board member have been charged with embezzlement (they denied it but resigned from their charter posts). Of the 15 teachers at the charter in September, only five remain, and the charter will take fewer students in special education and from low-income families than Smith has.

Reviewing the situation at the school, Juan Gonzalez wrote, " One day soon, our city will wake up to discover that Bloomberg's mad rush to create hundreds of independent charter schools has unleashed bigger financial scandals than in the bad old days of community school boards."

Evangelista, though, said charters are subject to intense scrutiny. "The governing system for charter schools makes them more publicly accountable than the system that existed before mayoral control," he said.

In the Classroom

At Harlem Link Charter School on West 112th Street, these controversies seem far away. In one class students work on their own in small groups. In another students devise a Venn diagram to chart the similarities and differences between strawberries and oranges. One difference most agree on: You can eat all of a strawberry, but few people eat orange peels.

Siri Cortes, a fifth grader who has been at Harlem Link since kindergarten considers that. "You can't eat the leaves," she said.

In the hallway, Siri expresses enthusiasm for a lot of what goes on in school and gets excited when Evangelista tells her about a Madeleine L'Engle book featuring a character named Siri.

Asked whether she likes Harlem Link, Siri pauses, "I don’t know how I could dislike it when it's the only school I've ever been to," she said.

Paterson's Plan for CUNY and SUNY Draws Criticism

A plan to give the City University of New York and the State University more autonomy is being praised by the chancellors of those schools. But many in the legislature, as well as advocates, worry the proposal represents a step toward privatization of the two systems and could put their programs beyond the reach of many of the state's less affluent residents.

Gov. David Paterson's Higher Education Empowerment and Innovation Act, would allow SUNY and CUNY more control over how much they charge for tuition, how they set prices for different programs and how they do business in general. Currently the legislature sets tuition and generally reserves tuition hikes for times when the state is in financial trouble -- times like now.

"We have a crazy system in New York in how we finance higher education" said State Budget Director Robert Megna during a recent budget presentation, adding that the system is "at the heart of why they [SUNY and CUNY] haven't been able to accomplish things they wanted to."

At state budget hearings on higher education Wednesday, Senate Finance Committee Chair Carl Kruger and Assemblyman Joel Miller used the term "privatization" to describe the proposal. Supporters of the governor's initiative prefer to call it "empowerment."

Different Schools, Different Tuition

The legislation would allow the boards of trustees for SUNY and CUNY to implement a tuition policy that would enable them to raise tuition by an amount equal to two and a half times the five-year average of the Higher Education Price Index. That is a nationally recognized inflation index that tracks what drives the price of higher education.

Under the governor's plan, SUNY and CUNY would collect tuition and disburse it to individual universities freely, rather than funneling it back into the state's general fund. Trustees would also be allowed to charge differential tuition rates for different academic programs and campuses. Currently all four-year CUNY campuses charge in-state residents $4,600 a year; SUNY campuses charge $4,970.

Megna said that the plan makes sense but will likely give legislators pause. The plan also will give the universities more flexibility in purchasing and in use of land. Megna relayed a story about two administrators, one from Cornell and one from SUNY, who needed the same device. Cornell got it in six weeks; thanks to the state's control of SUNY's contracts and purchasing it took SUNY six months to acquire the same tool.

"It's a fundamental rethinking of how we should have a stable relationship with SUNY and CUNY," said Megna.

Concerns About Cost

Opponents of the measure like Miller say that Paterson wants to give state colleges the ability to raise tuition themselves, rather than having the legislature set tuition as it currently does, because the state is in financial crisis and can no longer properly fund public higher education.

They say Paterson's measure will lead to steep tuition increases that will hurt low-income families. Miller and other critics worry that differential tuition will lead to lower-income college students being priced out of some SUNY and CUNY campuses and programs.

SUNY Chancellor Nancy Zimcher said that SUNY is committed to making all programs affordable and accessible and would use tuition increases and differential tuition responsibly. She and other supporters of the measure say most universities around the country vary their tuiton.

CUNY chancellor Matthew Goldstein testified that he basically supports the governor's legislation. He said it would essentially institute the kind of rational tuition policy he has been advocating for years. "CUNY has long supported differential tuition by program, informed by market competition and price elasticity," Goldstein said in his testimony. He said the new tuition structure will give students a better idea of what their college education will actually cost.

Miller countered that state has been extremely predictable in the way it cuts funding and raises tuition during tough economic times. "It’s a shame. Its wrong," he said. "But it is predictable." Paterson has proposed cutting SUNY funding by $95 million and CUNY funding by $47 million this year.

More Students, Less Money

According to the Professional Staff Congress, a union that represents CUNY staff, the state's funding for full-time equivalent students has dropped precipitously over the last two decades. In 1990, the state provided about $14,000 per full-time equivalent student. Now that figure has dropped to $9,000. And CUNY has seen its enrollment explode during that time: CUNY now has 260,000 degree credit students, with 65,000 more students enrolled than it had in 1999.

Community colleges have seen the greatest spike. Paterson's current budget proposal would reduce aid to community colleges by $285 per full-time equivalent student. That means tuition for a student attending community college will increase.

And to make things more difficult for students with moderate resources, Tuition Assistance Program funding would decrease by $93 million overall. All students would have their aid reduced by $75, while students studying for two-year associate degrees would have their maximum possible tuition assistance grant lowered from $5,000 to $4,000.

Empowerment or Cop Out?

Groups representing students such as the New York Public Interest Research Group and unions such as the Professional Staff Conference say that Paterson's empowerment act is designed to let the state off the hook when it comes to properly funding public education while making higher education increasingly unaffordable.

"By allowing CUNY and SUNY to set their own tuition levels, free from legislative oversight and public accountability, and by making zero commitment to match any tuition increases with additional state dollars, the governor's proposal essentially takes the public out of public higher education," testified Barbara Bowen president of Professional Staff Congress.

"While the governor is proposing privatizing education he is also proposing major cuts. They are pulling the rug out from under us," Bowen told the Gotham Gazette.

"Public education ought to be funded publicly," said Fran Clark of NYPIRG. By giving the universities more autonomy, the new system will make it easier for the state to impose cuts." Clark said he finds it hard to believe that legislators will rush to support Paterson's proposal. "I don't know of any legislative body that is in a hurry to cut the purse strings."

Legislators Worry

Legislators certainly seem to be wary of the act. Senate Higher Education Committee Chair Toby Ann Stavisky said she shares concerns that lower-income students may be priced out of SUNY and CUNY. "I am committed to making sure SUNY and CUNY remain an accessible, affordable, quality education."

Sen. Jose Serrano said that public higher education is heading in the wrong direction in New York. "For a generation, CUNY was free, and it produced great attorneys, great public servants," he said, "It really did pay for itself. We got back what we gave ten-fold."

Now, Serrano said, Paterson is looking to let SUNY and CUNY raise tuition without guaranteeing any increase in education aid, and he thinks that is a recipe for ensuring that residents of his Bronx and Manhattan district will not be able to afford higher education. He said that, in effect, will mean that public higher education in New York has failed.

Not many of Paterson's initiatives are finding much support from legislators but Serrano said his analysis of the Higher Education Empowerment and Innovation Act will come down to how it will affect the communities he represents. "In the end we will look at the numbers and proposals and ask does this promote stability?"

Keeping Public Education Public

"Jonas Salk," said Bowen, bringing up the man who discovered the first safe and effective polio vaccine and was a graduate of the City University of New York. "Think about all the good done by that one person!” She added, “This system is meant to train our next generation of public servants."

Bowen and others are concerned that differential tuition could prompt schools to charge more for such intensive programs such as pre-med or engineering, driving low-income students out of them.

Goldstein told legislators that differential tuitions will mostly be used in graduate programs, and any tuition increase would likely be put back directly into the program. Zimpher insisted that SUNY is committed to making sure its programs are accessible to low-income students.

Bowen said she thinks the financial downturn is exactly when the state should better fund its higher education system. She thinks this is the last moment the state should cede any of its involvement.

The union wants the state to restore $121 million in funding to senior colleges and $39 million in funding to community colleges that has been cut over the last two years. And that is something unions, students groups and university heads can agree on -- they want the state to reconsider all of Paterson's proposed cuts.

"It's crazy during this crisis to make public education less accessible," said Bowen. "We want the legislature to fight back against the proposed cuts. We hope the governor's empowerment act isn't enacted. We want the legislature to restore some of what has been lost. We are well aware the state is in financial dire straits, and it may be difficult, but we need to support public education."

Latest Round of School Closings Sparks Heated Opposition

Standing in front of a crowd at Abyssinian Baptist Church, Danisha Williams spoke about how she had continued on after losing her mother and father.

"The teachers at Maxwell said, 'Danisha, you're too strong. There's no such thing as giving up,'" she related. "It changed me from the clothes I wore, the way I spoke, the way I looked at things." And so, she said, "I did it."