The Citizen

Â

|

The Citizen is in another location. If you are not automatically directed to the correct page, click the following link: |

The Passion for Religion Ebbs

As the Passion of the Christ continues to break box office records, Christians observe lent, Jews prepare for Passover, the attorney general holds morning prayer services and politicians routinely voice their religious conviction from the stump, one might get the impression that Americans are becoming more and more religious, and that they are increasingly uneasy about such secular and scientific trends as abortion, equality for gay people, and stem cell research. Yet, data from the 2001 American Religious Identification Survey shows that Americans, and New Yorkers, are actually becoming less religious. About 30 million adults were found to have no religious affiliation, which is almost double what it was a decade earlier (from 8.2 to 14.1 percent). In New York State, there are about 1.9 million such residents (or about 13.4 percent of the population), and in New York City, we can infer, some 14 percent of the population says it has no religious affiliation, which, again, is about double what it was a decade ago.

The survey results for New York State, presented in the accompanying table present few other surprises. Together all Christian groups have declined, from 80 percent to 71 percent. Most Catholic and Protestant groups, along with the Mormons and the Jews, report substantial drops in religious identification, while Muslims and Eastern religions more than doubled their adherents. Those few subscribing to the more evangelical and fundamentalist versions of Christianity also show substantial increases in New York. Apparently, the non-Christian religions of the immigrant communities and those of the Christian right are on the upsurge, but the more conventional religions are losing popularity. At the same time, though, as I said, there is a gain in people having no religion at all.

Unlike those in the United Kingdom and some other countries, the United States Census does not ask for religious identification. To fill that gap, academic researchers in 1990 and again in 2001 were able to raise funds to carry out a large scale nationwide survey of religious identification. In 1990, for the first time ever, they surveyed over 110,000 US adults about their religious identification. Results from the National Survey of Religious Identification were reported in the seminal book One Nation Under God: Religion in Contemporary America by Barry Kosmin and Seymour Lachman. In 2001, Kosmin along with Ariela Keysar and the late Egon Mayer of the CUNY Graduate Center conducted a survey of about 51,000 adults from the lower 48 states. That study produced two reports, and now the researchers are working on a book interpreting their findings. Since the United States does not track religion as part of the census, the results from these surveys give us the best information available on the changing patterns of religious identification. Both surveys used individual responses to questions to measure religious identification.

The increase in religious identification in New York among Muslims, and those from Eastern religions, reflects the increase in the number of immigrants from Asian and Middle Eastern countries. What is much more difficult to account for is the large increase in those stating that they have no religion. While some of the growth is among those who say they are atheist or agnostic, the vast bulk of those giving a "no religion" response do not identify with such labels. Those having no religion tend to be white, unmarried, young and male.

Some researchers cite growing evidence, that America and New York City are truly becoming a belief bazaar, where people essentially pick and choose among competing viewpoints, including no religion at all. In a more detailed survey among 17,000 respondents, ARIS results found that about one-sixth of the adult population had switched religions. The report notes, "switching has involved not only the shift of people's spiritual loyalties from one religion to another -- which could reflect some kind of spiritual seeking -- but also and perhaps more importantly, a dropping out of religion altogether." Overall about one-fifth of those with no religion switched to that view from an established religion, while only five percent of those with no religion found religion.

The data for New York and for the nation make it plain that, despite the visibility of the few, for a large segment of the population, conventional religion is losing its appeal.

Andrew A. Beveridge has taught sociology at Queens College since 1981, done demographic analyses for the New York Times since 1993, and provides expert testimony on a range of cases, including housing discrimination. The opinions expressed are his alone.

Imprisoned In New York

Criminals are among New York City’s most popular exports. According to a recent study, about 44,000 state prisoners, or two-thirds of the entire state prison population, are from New York City. Yet only 3,000 of these inmates are in state-run jails that are actually located in New York City. The rest are trucked up to state-run prisons upstate. While inconvenient to their relatives, their relocation is a huge benefit, both economically and politically, to rural counties upstate – at the expense of New York City.

More Than 100,000 Prisoners

All together, there are some 108,000 people imprisoned somewhere in New York State, according to the 2000 census.

- 6,500 are in federal prisons or detention centers

- 34,000 are in local jails

- 66,000 are in state prisons

Only about 21,000 of these 108,000 were housed in New York City

- 2,600 in federal prisons and detention centers

- 15,000 in local jails,

- 3,000 in state prisons

Many people held in local jails are awaiting trial or serving relatively short sentence. Those convicted of more serious local crimes serve time in state prisons.

Most of those prisons are upstate, as the accompanying map shows.

All prisons built since 1982 have been constructed upstate. There are so many inmates in sparsely-populated rural counties upstate that nearly 30 percent of all new residents in Upstate New York in the 1990s were prisoners, according to a Brookings Institution study. Upstate gained 21,000 new prisoners during the decade, an increase that was accompanied by a growing number of prison staff, as well as inmates' relatives. Upstate has a larger share of prisoners than the nation as a whole -- 1.1 percent of its population in 2000, compared to just 0.7 percent of the U.S. population.”

The Costs

Since the average cost of housing a prisoner in New York is upwards of $40,000 the economic impact of having a prison is enormous. Resources spent on prisoners cannot go for other public activities, so resources are diverted from education, housing and other services to housing prisoners.

The Benefits

Unlike the residents living at-large who surround them they are much more likely male (over 90 percent), black (about 57 percent), and Hispanic (about 30 percent.) Most of upstate New York, of course, is predominantly non-Hispanic white. The only way that such residents are truly welcomed upstate is when they are locked away in cells.

But why are they welcomed even then?

The answer is: they are officially counted as upstate residents.

Services that are provided to them stimulate the local economy, which is frequently in decline.

The prisoners also supply another unique benefit to the upstate region. They allow it to have more voting power than its population would merit if prisoners were not there. Since prisoners cannot vote but are counted in redistricting, they give upstate the benefits of extra people (and cash) without the locality being obligated to address any of their needs. Legally, residency is generally determined based upon both where one is domiciled and the intent to remain there. So a prisoner taken from his home in New York City and counted in an upstate prison, which he expects to leave as soon as he can, is not really an upstate resident. The census could count such individuals where they once lived, as they do overseas military troops. Instead, the census, in effect, gives that population to the upstate New York City rural areas or other areas where prisoners are housed. A new and aptly named web site “Prisoners of the Census” developed by Soros Justice Fellow Peter J. Wagner gives many more details on these impacts.

The impact of this practice in New York State is large. In effect, about 44,000 people are arbitrarily transferred from New York City to upstate, and redistricting for every level of state office is affected. For instance the following Senate districts would be legally underpopulated and need to be redrawn were it not for the prison population:

- District 45 (Betsy Little whose district includes Clinton, Essex, Franklin, Hamilton, Warren and Washington Counties),

- District 47 (Raymond Meier whose district includes Lewis County and parts of Oneida and St. Lawrence Counties); ),

- District 48 (James Wright whose district includes Jefferson and Oswego Counties and parts of St. Lawrence County), ),

- District 49 (Nancy Hoffman whose district includes Madison County and parts of Cayuga, Oneida and Onondaga Counties), ),

- District 51 (James Seward whose district includes Cortland, Greene, Herkimer, Otsego, Schoharie Counties and parts of Chenango and Tompkins Counties), ),

- District 54 (Michael Nozzolio whose district includes Cortland, Greene, Herkimer, Otsego, Schoharie Counties and parts of Chenango and Tompkins Counties) and ),

- District 59 (Dale Volker whose district includes Wyoming County and parts of Erie, Livingston and Ontario Counties)

At the same time several districts in New York City, most likely in Queens, would be over populated, if the prisoners were counted as residing in the city.

Unwilling Sojourners

According to one commentator New York City prisoners are not residents of upstate – they cannot vote or otherwise participate in the local society -- but merely “unwilling sojourners” there. Many are arrested on drug offenses and held for long mandatory minimum sentences. This might help explain why the upstate legislators, most particularly the State Senators from rural upstate districts, are very strong supporters of keeping the Rockefeller drug laws intact.

Once New York City prisoners finish their sentences, they leave upstate and move back to the city with little or no services or reentry assistance beyond that provided by social services and the probation officer.

In sum, New York City residents who become prisoners based in large part on the Rockefeller drug laws are transported upstate to be exploited both economically and politically in largely Republican areas.

Andrew A. Beveridge has taught sociology at Queens College since 1981, done demographic analyses for the New York Times since 1993, and provides expert testimony on a range of cases, including housing discrimination. The opinions expressed are his alone.

The Citizen

Â

|

The Citizen is in another location. If you are not automatically directed to the correct page, click the following link: |

Who Are NYC's Republicans?

As the Republicans prepare for their first-ever national convention to take place in New York City, are they struggling to come up with a welcoming committee of native New Yorkers? Surely, Republican Governor George Pataki will play a part, but what about Republicans specifically from the city? It is true that for almost 10 years New York City's mayor has been a Republican, but both Rudy Giuliani and Michael Bloomberg used to be Democrats, and they won election in part because they were willing to abandon many now-core national GOP positions, including banning abortion and not granting gay people full equality.

The convention could easily give a primetime slot to every Republican elected official from New York City. There are only 13 of them. That includes all three levels of government, federal, state and city:

- Only three of the 51 New York City Council members are Republican.

- Only two of the 65 State Assembly members are Republican.

- Only four of the 25 State Senators whose districts are completely in New York City, are Republican. (Add to that Guy Vellela, who represents a very gerrymandered district that corralled white voters in the Bronx and Westchester County into a district that looks like a white donut around a black center).

- Only one Congressional seat out of the 14 that include New York is represented by a Republican.

(To get to 13, add the borough president and district attorney from Staten Island).

And even most of these GOP office-holders do not represent Republican-majority districts.

Where Do Republicans Live In NYC?

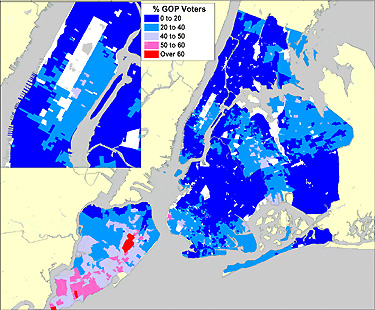

The small number of Republican elected officials is not surprising. Only 13 percent of the 3.7 million registered voters in New York City are registered as Republican, according to the New York City Board of Elections.

The smallest percentage of Republicans is in the Bronx (9.3 percent). Listing the other boroughs in ascending order, they are:

- Brooklyn (12.1 percent)

- Manhattan (14.1 percent)

- Queens (18.1 percent)

By far the largest percentage of Republicans is in Staten Island (37.8 percent). Only in Staten Island are there contiguous areas of Republican strength, as evident in the accompanying map showing the concentration of GOP voters throughout New York City.

Todt Hill, an affluent area of single-family homes, contains the most Republican-majority election districts in the city. The extended area around Todt is also reliably Republican, responsible for electing five of the 13 GOP public officials in the city (a state senator, two assembly members and two council members).

No other area in NYC is so pervasively Republican, not even the Upper East Side. Indeed, even in that affluent enclave (where four years ago zip code 10021 supplied the most campaign funds to both Bush and Gore of any zip code in the United States), Democrats outnumber Republicans.

In Queens there are a few pockets of Republican strength in Glendale, Middle Village, Forest Hills, and Howard Beach as well as Douglaston, Whitestone, and College Point. There are two GOP State Senators and one council member from Queens.

Election districts in New York City with high proportions of GOP enrolled voters, are areas with high proportions of whites living in owner-occupied homes.

How Different are NYC’s GOP Voters from Other NYC Voters?

Republicans in New York City are demographically different from other city adult residents.

GOP members are much more affluent. About 31 percent of them have incomes above $75,000. This compares to only 16 percent of New Yorkers as a whole, according to an analysis of the raw data from a CBS-New York Times poll of New York City completed in June 2003. (Because the number of respondents is only 962, the results reported are approximate.)

Republicans are about half as likely to report that their financial situation has worsened recently--24 percent of Republicans say that, compare to 42 percent of all New Yorkers.

Republicans are more likely to own their own home (47 percent versus 30 percent.)

About three-quarters are white compared to less than half of the rest of the New York City population. Interestingly, though, there is as large a proportion of Republicans who are Hispanic (28 percent) as of New Yorkers in general.

Republicans are more likely to be between 45 and 64 years old than the population as a whole (37 percent versus 27 percent.), and just about as likely as the population as a whole to have kids living with them (35 percent.)

They are more like to identify with a religion, 81 percent compared to 76 percent. While 57 percent of New York City Republicans are Catholic, only 36 percent of non-Republican New Yorkers are Catholic; similarly 14 percent of Republicans they are Jewish compared to 8 percent of the rest of New Yorkers.

But Republicans in New York are just about as likely to be in a union or have a union member in the family--26 percent versus 25 percent -- and even more likely to have a municipal worker in the family--25 percent versus 17 percent.

And Republicans are more likely to smoke -- 29 percent versus 19 percent.

Andrew A. Beveridge has taught sociology at Queens College since 1981, done demographic analyses for the New York Times since 1993, and provides expert testimony on a range of cases, including housing discrimination. The opinions expressed are his alone.

Five Hidden Facts About Housing (An Analysis Of Data From The Housing and Vacancy Survey)

The New York Housing and Vacancy Survey (known to those interested in housing as HVS) is conducted every three years (unless it is a Census year) on commission from New York City's Department of Housing and Preservation. The point of the survey is to determine the rental vacancy rate in New York City. If the vacancy rate should go above five percent it would be the end of rent regulation in New York City, because of a provision in the 1974 Emergency Tenants Protection Act. After the survey is completed, those interested wait for the first release of information, which includes the vacancy rate(in pdf format).

The U.S. Census Bureau recently released the raw data from the 2002 Housing and Vacancy Survey. My analysis of these data revealed some hidden and surprising facts about housing in New York. Here are five such findings:

1. Rent regulation seems to be vanishing in New York faster than many thought. In just three short years, according to an estimate I made, some 90,000 apartments in the city were de-regulated, or about eight percent of the total number of 970,000 stabilized apartments in New York. This estimate takes into account some of the changes in the survey sample between 1999 and 2002. It also only considers those apartments subject to the 1974 Emergency Tenants Protection Act. It excludes those that have been "controlled " as well as apartments in other categories, e.g. Public Housing, loft conversions, etc.

2. Two-thirds of all non-regulated apartments in Manhattan now rent at $2,000 or more. In 1999 this figure was slightly below half. Manhattan also is the borough with the largest drop in stabilized units. The Lower East Side / Chinatown and Greenwich Village were the two neighborhoods in New York City with the highest percentage increases for stabilized apartments. (I only included neighborhoods with enough units in the sample to make comparisons meaningful.) As these trends continue more and more Manhattan apartments can and will be removed from stabilization.

3. In every neighborhood in Manhattan, except for Washington Heights the median rent for those in stabilized apartments is less than three-fifths of those in non-stabilized apartments. For all apartments in Manhattan the stabilized median is 38 percent that of the market rate median. In the Upper West Side, for example, the median rent for those in market rate apartments is $2,500; for those in stabilized apartments the median rent is $924. So those in rent-stabilized apartments in Manhattan enjoy very large subsidies.

4. The largest increase in rents in market rate apartments occurred in the outer boroughs. Specifically Bay Ridge, Park Slope and Bedford Stuyvesant in Brooklyn, Astoria and Woodside /Sunnyside in Queens all saw market rate rents increase by thirty percent or more. These areas are undergoing new construction and renovation of existing structures.

5. In general stabilized and market rent housing was slightly more affordable in 2002 than in 1999. In 1999 exactly half of such renters paid more than 30 percent of their income for housing, and 26 percent paid more than half. By 2002 , the first such group dropped by one percent (49 percent of such renters paid more than 30 percent of their income for rent), the second group went up one percent (27 percent paid more than half). Mostly, however, this reflects income gains. New York still continues to be one of the most unaffordable housing markets in the United States.

The implications of these findings, of course, can and will be debated by advocates for tenants and landlords. It does seem plain however, that the main beneficiaries of rent stabilization are those living in such apartments in Manhattan, and a few other "hot" neighborhoods. Yet, the trend towards freeing apartments from the ETPA means that more and more of these units will be lost to stabilization in Manhattan as rents are pushed above the $2,000 cut off. In most of the rest of New York City, few stabilized apartments would ever fetch $2,000. Indeed, outside of Manhattan the median rent for stabilized apartments is about 84 percent of the rent of those that are "market rate." At the same time, as more and more Manhattan apartments leave stabilization, fewer and fewer households will be able to afford to live there.

ABOUT THE SURVEY

Because the Housing and Vacancy Survey has the very important purpose of determining whether the system of rent regulation should remain in place, it is carefully designed and carried out by the Census Bureau. The two federal and city agencies put a great deal of effort in constructing a sampling frame of housing units in New York City that matches the housing in the various categories of regulation. About 17,000 units are surveyed. The survey also presents data on a large array of interesting things, including income, education, household structure, and immigration. In many ways it functions as an update to the decennial census. Unlike the census, though, it is conducted by personal interview. Each unit that is initially judged vacant is subject to further screening both to find out if it is truly vacant, and if it is vacant whether or not it is truly available to be rented. The vacancy rate is based not upon total units, but rather upon total units that are vacant and available to be rented. Eventually a comprehensive report will be issued by Department of Housing and Preservation, which is usually entitled Housing New York City. Before that report is released, the data themselves are made available to researchers.

Because the 2002 survey uses a sample based upon the 2000 Census and the 1999 Survey is based upon the 1990 Census simple comparisons become more difficult. To make my estimate of the change in the number of stabilized units, I adjusted the 1999 survey based upon results from the 2000 Census compared to the 2002 Vacancy survey. During the summer of 2004, the Census plans to provide data reweighted so that they are based upon the 2000 Census for all of the surveys conducted since 1993. At that point we can assess how accurate were my estimates.

Andrew A. Beveridge has taught sociology at Queens College since 1981, done demographic analyses for the New York Times since 1993, and provides expert testimony on a range of cases, including housing discrimination. The opinions expressed are his alone.

Young, Graduated and in New York City

Every year New York City draws young people in pursuit of fame, fortune, excitement and relevance. They are a popular subject for literature, theater, and Gotham Gazette (see Gotham Gazette's newcomers weblogs and issue of the week article). But who exactly are the recent college graduates in the city? Where do they come from? What do they do for a living? What sorts of living arrangements do they have?

It is possible to paint a demographic portrait of younger college graduates in the city and compare them with the rest of the population between 18 and 65. To do this I used a newly released data file from the 2000 census. Of course, the severe downturn in the economy in the past three years may have changed the picture somewhat. Still it is instructive to look at who the young college graduates were in 2000.

About 273,000 New Yorkers were college grads 28 years of age or younger in 2000 who were either not enrolled in a graduate degree program or if they were enrolled were also working full-time. (Defining them this way eliminates those who are primarily pursuing graduate education). About 57 percent were female, compared to 52 percent for the rest of the population 18 to 65. About 59 percent were non-Hispanic whites, 11 percent black, 16 percent Asian and 10 percent Hispanic. So these young grads are much more female, much more white, and much more Asian and much less black and Hispanic than the population at large. About 10 percent lived abroad in 1995, while 45 percent lived in New York City and an equal number moved here from elsewhere. Thus many obtained their college degrees in the New York City's colleges, most particularly, of course, CUNY. About 18 percent were non-citizens compared to 26 percent of the rest of the population.

Fully 84 percent of recent graduates were working in 2000, compared to only about 60 percent of the other non-senior adults. Almost two-thirds of college grads (compared to less than one third of the others who are working) were in higher status occupations: management, business and finance, or professional and related occupations. Over half use public transit to get to work (much higher than the third reported by the rest of the population), and the commute took them a median of a half hour. Though the recent college graduates and others in New York City reported 40 median hours worked per week, the recent graduates earned a median of $32,000 per year compared to $26,000 for the others.

As to living arrangements, about one-fifth were married, compared to almost half of the rest of the population. About one-quarter of the recent grads live with their parents, while about one-third lived with roommates. On average the grads lived with 1.66 other persons, while the rest of the adults lived with 2.44. They did pay a lot more to house their smaller households -- $1050 compared to $725 for median rent. This is not surprising, since as the accompanying map shows, the highest concentration of recent grads were in such "hot" areas as Greenwich Village, Chelsea, Lower Manhattan, Williamsburg, Park Slope, and the Upper East Side. One can easily see that they are very oriented towards Manhattan, especially Manhattan downtown.

Thus the young college graduates such as those depicted in the Broadway puppet musical Avenue Q, when compared to New Yorkers at large are quite privileged. Many work in good jobs and earn decent livings. They flock to the more fashionable residential areas in the city and are able to pay the rents to live there. They renew the ranks of the "creative class" recently identified by Professor Richard Florida as very important for urban growth. So though it may be a frightening and difficult prospect for these quarter million new recruits to New York City adulthood, it seems that the city is good place to be young, and it is good for the city that they are here.

Andrew A. Beveridge has taught sociology at Queens College since 1981, done demographic analyses for the New York Times since 1993, and provides expert testimony on a range of cases, including housing discrimination. The opinions expressed are his alone.

Back To (Public and Private) School

The back-to-school experience in New York City depends on who you are and where you live. The most obvious distinction is between public and private school. Public schools educate about 1.14 million of the city's kids, or more than 80 percent of the total student-age population. The remaining 266,000 students go to private school.

An analysis of recently released data from the 2000 census confirms what any educator will tell you: Private school kids are far richer and whiter than their public school counterparts.

The schools that many New Yorkers conjure up when they think of "private school" -- Fieldston, Horace Mann, Brearley, Dalton and Collegiate, and perhaps two-dozen other such institutions -- actually serve only a small fraction of those who go to private schools. The vast majority of private school students are enrolled in schools associated with either the New York Archdiocese, which has about 115,000 students in 293 schools in the Bronx, Manhattan and Staten Island (as well some suburbs), or the Brooklyn Diocese, with 70,000 in 178 Brooklyn and Queens schools. There are also a large range of religiously-affiliated schools, including Yeshivas.

The United States Census Bureau makes no distinction between independent private schools and those that are religiously affiliated.

This makes the statistics even more startling.

| 2000 NYC SCHOOL KIDS |

%TOTAL

|

%PUBLICĂŠ

|

%PRIVATEĂŠ

|

| h |

1,409,221

|

1,142,935

|

266,286

|

| h |

h

|

81.1%

|

23.3%

|

| RACE AND HISPANIC STATUSh | |||

| WHITE NON-HISPANIC |

22.8%

|

15.9%

|

52.6%

|

| BLACK NON-HISPANIC |

30.3%

|

32.8%

|

19.4%

|

| AMIND NON-HISPANIC |

0.4%

|

0.4%

|

0.3%

|

| All OTHERS NON-HISPANIC |

12.3%

|

13.3%

|

8.0%

|

| HISPANIC |

34.2%

|

37.6%

|

19.7%

|

| SPEAK NON ENGLISH LANGUAGE AT HOME (FIVE YEARS OLD OR OLDER) | |||

| YES |

48.6%

|

50.3%

|

41.1%

|

| ABILITY TO SPEAK ENGLISH AMONG THOSE WHO SPEAK NON-ENGLISH LANGUAGE AT HOME (FIVE YEARS OLD OR OLDER) | |||

| VERY WELLĂŠ |

67.5%

|

66.6%

|

72.0%

|

| WELLĂŠ |

22.3%

|

23.1%

|

18.3%

|

| NOT WELLĂŠ |

9.0%

|

9.1%

|

8.7%

|

| NOT AT ALL |

1.2%

|

1.2%

|

1.0%

|

| CITIZEN STATUS | |||

| BORN U.SĂŠ |

80.5%

|

78.3%

|

89.9%

|

| BORN OUTLYING |

1.3%

|

1.5%

|

0.4%

|

| ABROAD/AM PAR |

1.0%

|

0.9%

|

1.4%

|

| NATURALIZED CITIZEN |

3.6%

|

3.9%

|

2.2%

|

| NON-CITIZEN |

13.6%

|

15.4%

|

6.1%

|

| HOUSEHOLD TYPE | |||

| FAMILY MARRIED COUPLE |

56.0%

|

51.8%

|

73.9%

|

| FAMILY MALE HEAD |

5.7%

|

6.1%

|

4.0%

|

| FAMILY FEMALE HEAD |

38.0%

|

41.7%

|

21.8%

|

| NON-FAMILY MALE HEAD WITH OTHERS |

0.2%

|

0.2%

|

0.2%

|

| NON-FAMILY FEMALE HEAD WITH OTHERS |

0.2%

|

0.2%

|

0.1%

|

| EMPLOYMENT STATUS BY FAMILY TYPE | |||

| NOT IN FAMILY HOUSEHOLD |

0.3%

|

0.4%

|

0.3%

|

| MARRIED COUPLE/BOTH IN LABOR FORCE |

26.8%

|

24.4%

|

37.2%

|

| MARRIED COUPLE/HUSB IN LABOR FORCE |

17.6%

|

15.7%

|

25.7%

|

| MARRIED COUPLE/WIFE IN LABOR FORCE |

4.2%

|

4.2%

|

4.4%

|

| MARRIED COUPLE/BOTH NILABOR FORCEĂŠ |

7.4%

|

7.6%

|

6.6%

|

| MALE HEAD/IN LABOR FORCE |

3.9%

|

4.1%

|

2.8%

|

| MALE HEAD/NILABOR FORCEĂŠ |

1.8%

|

2.0%

|

1.2%

|

| FEM HEAD/IN LABOR FORCEĂŠ |

21.5%

|

23.1%

|

14.5%

|

| FEM HEAD/NILABOR FORCEĂŠ |

16.5%

|

18.6%

|

7.2%

|

| HOUSEHOLD INCOME | |||

| UNDER $20,000ĂŠ |

29.4%

|

32.5%

|

15.9%

|

| $20,000-29,999ĂŠ |

12.6%

|

13.5%

|

8.7%

|

| $30,000-39,999ĂŠ |

11.5%

|

12.1%

|

8.8%

|

| $40,000-49,999ĂŠ |

9.2%

|

9.3%

|

8.6%

|

| $50,000-74,999ĂŠ |

16.8%

|

16.2%

|

19.7%

|

Private vs. Public School Students

As the chart indicates:

*About 53 percent of private school kids are (non-Hispanic) white, but only 16 percent of public school kids are white.

*Public school kids are twice as likely to come from households with less than $30,000 per year of income. But more than a third of private school kids are from households with incomes above $75,000, while only a sixth of public kids come from such households. Some eight percent of private school kids live in households with incomes above $200,000, while only about one percent of public school kids do.

*The families of private school kids are more intact, with almost three-quarters of them living in married couple families, while little more than half of all public school kids live in such households.

*Private school kids are more likely to use English at home, and more likely to have their parents in the work force.

Neighborhood Differences

This overall demographic portrait of NYC's school kids masks the fact that there are very large variations if sorted by neighborhoods. In Brooklyn, over 60 percent of the kids who live in community board 12, which is in and around the orthodox Jewish area of Borough Park, go to private school, while in community board 4, which includes heavily Hispanic Bushwick, only about 6 percent of kids go to private school.

Generally speaking though, the affluent neighborhoods are the ones with the highest private school enrollment, especially in Manhattan. Only 12 percent of students in Harlem (community board 10) attend private school, while on the Upper East Side (community board 8), it is 66 percent.

Other Manhattan neighborhoods:

Washington Heights - 11 percent

Greenwich Village - 44 percent

East Harlem - 14 percent

Murray Hill - 53 percent

Upper West Side - 39 percent

In Queens, almost all community board districts send close to the city-wide average of 20 percent to private school. In Staten Island, all districts have between 20 and 30 percent of students in private school. In the Bronx only the Co-Op City Throgs Neck area (District 10) has more than 30 percent of its school kids in private schools.

Simply put, areas in Manhattan that have high proportions of whites have high proportions of kids in private school. In the areas of Bronx, Brooklyn, Manhattan and Queens where there are very few white school kids, the proportion of students in private school is much lower. In mixed areas, where there are some white school kids but also blacks or both, then the private schools are much less diverse than the public schools. In all neighborhoods, as with the city as a whole, private school kids are more affluent and come from more intact families than do public school kids.

Andrew A. Beveridge has taught sociology at Queens College since 1981, done demographic analyses for the New York Times since 1993, and provides expert testimony on a range of cases, including housing discrimination. The opinions expressed are his alone.

Counting Drop-Outs

For at least 50 years, business leaders, politicians and parents berated students to “Stay In School.” Dropping out of high school condemned one to a life of economic uncertainty, welfare dependency or worse. Low dropout rates for high schools became a measure of school success, while high dropout rates were signs of failure. Where retention rates determined success, schools were expected to get all students to the goal of a high school diploma.

Recently “accountability” trends in education policy, culminating in the Bush administration’s ”No Child Left Behind” legislative mandate have shifted the focus from dropout rates to test performance. The results of such tests now determine which schools are “failing” and which are “succeeding.” Administrative actions to “restructure” failing schools and to let the students choose other schools hang in the balance. In New York State, the newly revised Regents Exams is to become the graduation standard, despite the recent flap concerning the scoring of the mathematics exam and the recent and the continuing 55 percent passing grade. In effect, New York State and City already grade high schools based upon the students who can be tracked from 9th grade to 12th grade. The percentage of students who graduate in four years is computed. However, students who transfer out often are not found in these figures, and many of them could be dropouts stop-outs or push-outs. Though New York State does not report, “dropout rates” per se, many individual schools often do give their dropout rate. Yet, no school knows its true dropout rate unless it knows where every single non-returning student goes.

Recent stories in the New York Times plainly show that attempts to cut the test failure rate increased the number of students pushed out of school in both New York City and Houston, which is the school district that Lod Paige, US Secretary of Education, used to lead. But the practice of students being dropped from the rolls in Houston and then inaccurately reported as transfers seems also to be popular in New York City. Because of such misleading reporting measuring dropout rates becomes even more elusive. Though a very well known phenomena among education insiders, these discrepancies in reporting dropout rates are hidden from the public.

The Census Bureau provides an excellent measure of dropouts. Instead of asking school administrators for a number saying how many students dropped out and computing a rate based upon enrollment, the census tabulates the number of persons 16 to 19, who do not have a high school diploma and who are not enrolled in school. From this one can easily figure out what the proportion of dropouts or non-attendees there are. According to the 2000 Census one finds that the 11.05 percent dropout rate in NYC is somewhat higher than the New York State rate of 8.77 percent. For non-Hispanic Whites the rate is 4.51 compared to the state rate of 5.31 percent. For Hispanics both the city and state rate is 18.08 percent, while for blacks the rate is 10.65 percent, slightly lower than the state’s 11.33 percent. Simply put, the dropout rate for Hispanics is about four times that for whites in New York City, while the rate for blacks is more than double that for whites.

Though it is based upon the neighborhood or city of residence (census tract or larger area), such a dropout rate becomes a very good measure in a setting where virtually all students go to public schools. Where many chose private or parochial school, the public schools still are the “last resort,” since they are obligated to take all comers. Since it is computed for most census areas, it also can directly compare one jurisdiction with another.

Many educators despise this measure. Indeed, an official at the National Center for Education Statistics, which includes it in their census compilation of school district data, told me that an urban school administrator threatened to kill himself (they assumed he was joking but he was very upset) if they continued to include it. Yet, the patterns that the census finds become quite telling and raise an issue not usually addressed: To what extent is dropping out of school a school- based phenomenon? In other words, to what extent can schools affect dropout rate? Or do some students from some areas just have a high propensity to leave school without a diploma. The accompanying map shows the dramatic variations in dropout rate among neighborhoods. Dropout rates are more than 25 percent in the South Bronx, around Flatbush in Brooklyn, and also in areas of high immigrant concentration in the Corona area in Queens. Can one really expect schools in such areas with highly mobile populations of limited means and many of them non-English speakers, to have dropout rates as low as those in Bayside, Queens in the affluent portions of Manhattan and Staten Island, in Riverdale, and in Forest Hills?

From “stay in school” initiatives to performance tests, officials recognize a high school diploma and the skills associated with it as vital to a student’s full participation in society. The judicial ruling (in PDF format) in the Campaign for Fiscal Equity case makes this plain and a right. The new trend in grading schools by test scores and holding administrators accountable for them may encourage educators to get rid of the poorly performing students. Using the census data on dropouts, soon to be available on a continuous basis from the census bureau, will allow educators and concerned citizens to monitor dropouts more honestly.

Andrew A. Beveridge has taught sociology at Queens College since 1981. Since 1993 he has done demographic analyses and consulted for the New York Times. He has provided expert testimony in districting and redistricting, housing discrimination, and numerous other civil rights cases in the metropolitan area and elsewhere. The opinions expressed in Topics are his alone.

The Vanishing Jews

The number of Jews in New York City fell below one million by 2002, according to the 2002 Community Study by the United Jewish Appeal-Federation of New York. But the real decline may be higher. The recent survey used methods for finding and defining Jews that were different than those used in the 1991 UJA-Federation survey. Indeed, several researchers resigned from the survey's Technical Advisory Committee from the survey, including Bethamie Horowitz, the director of the 1991 study; Charles Kadushin, an emeritus CUNY professor and researcher with the Cohen Center for Jewish Studies at Brandeis, and me. Each concluded that a direct comparison of 1991 and 2002 studies ignores the change in methods. Such an analysis would yield misleading conclusions.

Often such problems are written off as "merely technical," not affecting either the results or conclusions of the study. Here however, the technical disputes go to the heart of the survey. They revolve around two central questions: Who is a Jew? and How many Jews are there in New York City? Though downplayed somewhat in the new survey, which is not called a "population study" but rather a "community study," the fact of the matter is what determines Jewish identity and the size of the population remain central concerns of the organized Jewish community. In earlier topic page updates I discussed counting Muslims, gays, and the population of New York City. It is clear that when groups are put in charge of analyzing their own population, there is a temptation to overestimate their own size and thus their own importance.

WHO IS JEWISH?

Measuring religious or ethnic identification through a survey is not simple. The US Census Bureau, itself, experiences enough difficulty trying to disentangle the concepts of race, national origin, ethnicity and language. The First Amendment bars the Census asking questions about religion. In Great Britain, where the census used self-identification to classify religious affiliation, 390,000 people claimed their religious affiliation to be "Jedi Knight" in 2001. Sparked in part by an internet campaign, this Star Wars religion was just behind Hinduism and just ahead of Sikhism according to census returns in Great Britain.

People who belong to churches, synagogues or mosques usually know their religion. Religious identification becomes problematic for those with a lower level of affiliation. According to the 2002 Jewish Community study only 43 percent of Jewish households in the New York area belonged to a synagogue. For the 2002 study, when telephone interviews were conducted, the interviewer would tell the respondent that they were conducting the Jewish population study sponsored by the Jewish Federation, and then the respondent was asked if he or she were Jewish.

Some researchers think that this introduction and first question would make it more likely that those who considered themselves Jewish would continue the survey, while non-Jews would not continue. If such were the case, then the number of Jews would be overestimated by the survey. The screening introduction and first question were much more neutral in 1991 and thus may have led to a lower number of self-identified Jews in that survey.

HOW MANY JEWS?

According to the 2002 survey Jews make up about 12 percent of the eight million people who live in New York City. To arrive at this number the survey used a very complex set of techniques to "stratify" the sample (One of the four groups to which they divided up their sample was names taken from UJA membership lists). To complete the 4500 interviews used for the survey, they dialed 174,000 different phone numbers a total of 578,000 times. They contacted about 70,000 of these households, and 30,000 provided enough information to classify them as either Jewish or non-Jewish. Of these about 6,000 were classified as Jewish. Interviews were completed with about 75 percent of these. In 1991 the overall response rate was much higher than it was in 2002 if one uses the method for computing response rates favored by the American Association of Public Opinion Research.

To get to the estimates, the group carrying out the UJA Federation survey had to assume that they knew how many people were in each strata, and that the people that they contacted (about 1/5 of those they tried to contact) were the same as those they did not reach. This assumption is unlikely to be true. In fact, of course, they only really knew the size of the stratum made from the federation's list. To figure out how to weight all of the other respondents required using a combination of assumptions and updated census estimates. In summary, as those running the survey in 2002 have argued, it may very well be the case that the 2002 survey provided a better and higher estimate of the Jews living in New York than did the 1991 survey. However, if such is the case, it means that comparing the two surveys underestimates the decline in the Jewish population in New York City.

Despite the significant doubts about how comparable the new survey is to the old one, and how much the Jewish population has declined in New York City, the new study has much valuable information. Even if one is not exactly sure how many Jews there are, one can still learn a great deal about the Jewish community. One can only hope that the survey that the UJA Federation does in 2012 will be comparable to the one done in 2002. Then we will be able to accurately measure how much further the Jewish population may have declined in NYC.

Andrew A. Beveridge has taught sociology at Queens College since 1981. Since 1993 he has done demographic analyses and consulted for the New York Times. He has provided expert testimony in districting and redistricting, housing discrimination, and numerous other civil rights cases in the metropolitan area and elsewhere. The opinions expressed in Topics are his alone.

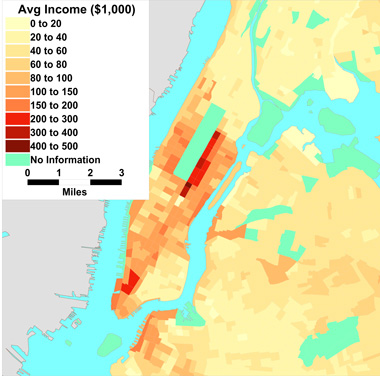

The Affluent Of Manhattan

The top fifth of Manhattan households received more than 50 times as much income in 1999 as the bottom fifth, according to analyses based upon Census 2000 data. Those in the top 20 percent averaged $366,000, those in the bottom 20 percent, $7,054. Those in the top group saw their average income increase $140,000, while those in the bottom group moved up only seven dollars. Manhattan is now the U.S. county with the highest disparity of income, surpassing the only county ahead of it in 1989, a former leper colony in Hawaii.

In 1989 a household needed at least $95,623 to be in the top 20 percent; by 1999 $115,800 was needed to make it to the top fifth, the highest amount for any county in the United States. When comparing income inequality among all 3,200 counties in the United States, Brooklyn ranks 24th, the Bronx ranks 35th, Staten Island ranks 234th and Queens ranks in the middle of the pack.

Who Is Affluent?

When considering New York City households, the characteristics of the affluent seem to prove F. Scott Fitzgerald's assertion that "the rich are different from us." Of the three million households in New York City in 1999, only about 110,000 (or about one in 26) had incomes above $200,000. The members of those households are very different from the rest of New York City's population. These elite are much more non-Latino white (83 percent compared to 42 percent of the population as a whole), and more likely to include a married couple (64 percent compared to 37 percent). Householders of the affluent households are better educated (79 percent of those over 25 with at least college compared to 28 percent.); more likely employed (93 percent compared to 73 percent), and more likely in managerial, business and finance, or professional and related occupations, (73 percent compared to 36 percent). Fully 56 percent of the affluent households consist of a married couple family with both partners in the labor force, which is 30 percent higher than for other households. The secret to affluence in New York, it seems, consists of having the right educational background (parents may be a big help here), succeeding in the right occupation, and having a spouse that did the same. Children of such couples certainly will have advantages over the children of the less affluent.

Affluent Areas

Digging a little deeper into income distribution for New York City, one finds high concentrations of upper-income households in the Upper East Side. In 1999, households in only 15 of the 2216 tracts in New York City had average incomes above $200,000. Twelve of those 15 tracts were on the Upper East Side, most bordering Fifth Avenue. This is no surprise of course; this is the way it has been for a century.

Two of the other three affluent tracts were in the Soho area near Wall Street, and one was in the Riverdale area in the Bronx that includes the private community of Fieldston, which surrounds the Horace Mann and Fieldston schools, with Riverdale school nearby.

When one walks up Fifth Avenue starting at 49th Street and continuing up to 96th Street every census tract through which one passes had an average income above $200,000 in 1999. This area of Manhattan contains one of the highest concentrations of the truly affluent in the United States. The co-ops along Fifth Avenue often sell for more than $20 million each. This is the neighborhood where a double-sized town house reportedly sold for more than $30 million, some of the doormen wear Ermine collars in the winter. Elite boutiques and other specialty stores dot Madison Avenue, where an appointment is preferred and one must ring a bell to be admitted.

The Upper East Side zip code 10021 generated the most donations for the presidential campaigns of 2000 of any zip code for both Bush and for Gore. Mayor Michael Bloomberg has one of his houses in the area. The Dalton and Brearley schools area located nearby, as is the Whitney, the Guggenheim and the Metropolitan Museum and many art dealers. Of course, Central Park is near, and supporters of the Central Park Conservancy disproportionately come from this area. After all it is their backyard.

Though the affluent are concentrated in the Upper East Side, they also dot many other neighborhoods throughout the city, especially newer neighborhoods in Manhattan (e.g. Tribeca, Chelsea, Battery Park), as well as posh outer borough neighborhoods, including Fieldston, Forest Hills Gardens and Brooklyn Heights. Despite economic uncertainty the predominance of the Manhattan affluent is unlikely to end anytime soon.

Andrew A. Beveridge has taught sociology at Queens College since 1981. Since 1993 he has done demographic analyses and consulted for the New York Times. He has provided expert testimony in districting and redistricting, housing discrimination, and numerous other civil rights cases in the metropolitan area and elsewhere. The opinions expressed in Topics are his alone.