The Fading Promise of Property Tax Reform

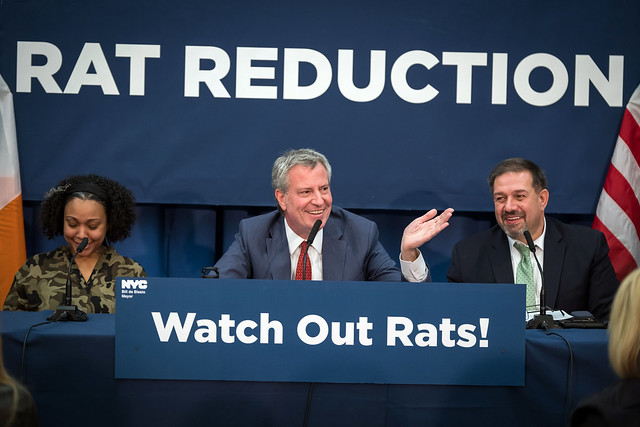

(photo: Benjamin Kanter/Mayoral Photo Office)

Despite promising that in his second term he would take on the challenge of property tax reform, Mayor de Blasio appears to be shying away as many leaders have done many times before.

New York City government is extremely dependent upon its property tax, which will generate roughly $30 billion this coming fiscal year, more than any other single revenue source. Not surprisingly, New Yorkers gripe about their property taxes almost as much as about the subways.

The laws and methods used to determine and assess the tax on individual properties are extremely complex and inequitable, but reforming them is a daunting task that will inevitably make some property owners unhappy. For that reason, elected officials have long avoided tackling the problem.

The current New York City property tax system was created in 1981. A lawsuit brought by law professor William Hellerstein in 1975 challenged the legality of the property tax system state-wide as violating the constitutional requirement that all similar properties be taxed equally.

After several missed deadlines, rejected proposals, and a last-minute override of Governor Carey’s veto, a new law was passed that divided properties in New York City into four “classes,” set different percentages of the value of each class of property to be assessed (assessment ratios), limited the amount of total property tax levy to be derived from each class (class shares), and provided for phase-ins and limitations on the growth of tax revenue from different classes so that no one property or type of property would experience a dramatic increase in value and taxation as the new system was phased in.

Thirty-eight years later, New York City looks quite different, property values have soared, and there have been many unintended consequences of the design of the property tax system.

Limitations on phasing in growth in value mean that properties within the same class are often taxed at very different effective rates and the limitations on class shares of the tax levy mean that different classes are shouldering disproportionate amounts of the burden of the growth in overall property value.

One of the most egregious outcomes is that co-ops and condos -- for which the market was very different in 1981-- are in the same class as rental properties and are assessed, not on their market value, but as if they were only generating rental income. The result is many high-end apartments assessed at far lower amounts than their real value; whole residential co-op and condo buildings in some parts of Manhattan are taxed at less than the actual sales prices of individual apartments in the building.

What is to be done? In April 2017 a group of frustrated real estate developers and landlords joined with individual property owners and supportive civic and civil rights groups (including Citizens Budget Commission, which I led at the time and filed an amicus brief) to file a new lawsuit, Tax Equity Now NY LLC vs. City of New York, et al. alleging the current property tax system discriminates against primarily people of color who are low-income renters and homeowners. The lawsuit was filed in the hope that, as had happened in response to the Hellerstein case, city and state leaders would respond with urgency and determination to develop a reformed taxation system.

Instead, both city and state defendants have strenuously resisted the suit, moving to dismiss it on the grounds that the plaintiffs aren’t directly impacted and/or that the state defendants aren’t responsible. The City also infuriated City Council members who wanted to intervene on behalf of the plaintiffs by opposing their application to file a separate brief.

The motion to dismiss was filed in June but it took until September 2017 for the judge to rule that the case could proceed and until February 2018 to rule that the Council members could not intervene in the case. The City filed an appeal and all further action in the case is on hold until that appeal is decided.

At a breakfast hosted by the Association for a Better New York the day before he was re-elected in November 2017, I asked Mayor de Blasio whether he was going to take on property tax reform. He answered directly and forthrightly that the system needs to be more fair and transparent but that we cannot afford to reduce substantially the revenue it generates and that relying on the judicial system to resolve the problem would be a mistake.

He estimated that it would “take a year or two” to bring all the stakeholders together and come up with the needed reforms and that it would require being “blunt” about the challenges. He said: “I am ready to do it….When I say something that definitively, I mean it…We will create tax reform.”

It took until May 31, 2018, more than a year after the Tax Equity Now case was filed and now a year ago, for the Mayor and the City Council Speaker Corey Johnson to announce the formation of an Advisory Commission on Property Tax Reform. Co-chaired by former city Housing Commissioner Vicki Been, then faculty director of the NYU Furman Center, and former First Deputy Mayor and then Interim COO of CUNY Marc Shaw, the commission was charged to “develop recommendations to reform New York City’s property tax system to make it simpler, clearer, and fairer, while ensuring that there is no reduction in revenue used to fund essential City services.”

No deadlines were specified, but the commission was instructed to conduct at least 10 public hearings.

All the public hearings and meetings were recorded and are available online. The last one was held this past February 28. Yet there is still no word on what the commission will recommend or when it will publish its report. The state legislative session is almost over so it is too late to achieve any changes this year and Been has become a deputy mayor with a lot more on her plate.

So the mayor’s promises notwithstanding, an opportunity to rationalize our property tax system and make it more fair has been missed and the commission looks more like a stalling device than a sincere effort to make tough decisions. Who wants to make New York property owners unhappy during a presidential campaign? As was the case four decades ago, it appears that we will need a lawsuit to compel elected officials to make tough decisions.

***

Carol Kellermann was president of Citizens Budget Commission from 2008 through 2018.

***

Have an op-ed idea or submission for Gotham Gazette? Email This email address is being protected from spambots. You need JavaScript enabled to view it.

***

Have an op-ed idea or submission for Gotham Gazette? Email This email address is being protected from spambots. You need JavaScript enabled to view it.

The Rainy Day Fund New York Needs

(photo: Ed Reed/Mayoral Photography Office)

With so much attention focused on the mayor’s presidential campaign, rent regulation renewal, and the state of the transit system, most New Yorkers are unaware they will have the opportunity this fall to vote to dramatically change their city government.

The 2019 New York City Charter Revision Commission is considering what amendments to the City Charter, which defines the structure and powers of city government, it will recommend to voters for a yes or no vote on the November ballot. Notable proposals include ranked-choice voting for local elections, enhancing community board review of land use proposals, and multiple changes to the city’s budget process.

One budget proposal the commission should approve and advance to voters in November is the creation of a Rainy Day Fund (RDF). An RDF is essentially a savings account that would allow city government to put away revenues received when the economy is growing and use them to stave off the most crushing service cuts and tax increases during an economic downturn or catastrophic emergency—the rainy days.

To weather the last two recessions, the city reduced police and ambulance staffing, cut library hours, suspended recycling, and increased personal income, sales, and property taxes. A well-structured RDF can ameliorate the need for this level of municipal pain, helping everyone from those who depend on city and social services to individuals and businesses feeling the strain of high taxes.

By and large, charter provisions and state laws enacted in response to the 1970s New York City fiscal crisis provide a strong budgeting and financial management framework that has served New York well—producing balanced budgets and prudent revenue estimates, while allowing the city to fund services New Yorkers desire.

Ironically, the city charter’s balanced budget requirement, among the most stringent in the nation, is what makes using an RDF impossible. Balancing the annual budget requires city services delivered in one year to be funded only with revenues generated that same year. Saving money in a strong economy to use later in a recession misaligns that timing, and violates the accounting rules relied on by the charter.

The solution is for the charter commission to leave the charter’s budgeting and financial management framework intact except to seize the opportunity to improve the charter by allowing an RDF, well structured to preserve both long- and short-term stability.

Absent an RDF, the city has devised legal work-arounds to provide some fiscal cushion. The city pre-pays expenses, freeing up money in the next year. The city has also used its Retiree Health Benefits Trust—money put aside to pay for municipal employees’ retirement health benefits—as a de facto RDF by paying for current bills with the trust’s assets rather than budget revenues.

These workarounds are problematic. Not enough money can be put aside; there are limits to what and how many expenses can be prepaid. In addition, there is no requirement to put money aside even in the best of times. Finally, using the RHBT as de facto RDF makes future taxpayers pay for current bills, which is hardly fair to the next generation.

True, the city has set aside some funds. The current financial plan includes $1.25 billion annually for reserves, but this pales in comparison to the need. Citizens Budget Commission estimates the projected three-year revenue shortfall from a recession comparable to the past two would be $15 billion to $20 billion.

How would a well-designed RDF be structured? The first step is to determine the right size of the fund. Based on past revenue trends, CBC estimates that 17 percent of tax revenues would be a good target size to mitigate a recession or emergency’s most damaging impacts.

Second, regular deposits should be required during economic expansions. CBC recommends annual deposits of 75 percent of all tax revenues in excess of 3 percent growth; this would allow spending on services to grow in excess of long-term inflation and still generate substantial RDF resources. Had this been in place during the current record-long recovery, the city would now have nearly $9 billion in its RDF.

Finally, withdrawals should be limited to periods of recession or emergency. Economic triggers should be defined in law and RDF funds should not all be used in one year.

By putting a Rainy Day Fund on the ballot, the charter commission would provide New Yorkers with an important opportunity to strengthen one of the few flaws in the city’s budgeting processes and would create significant momentum for the changes needed in state law.

Yes, some more political and proximate issues may be more galvanizing, and sadly, elected leaders and the public too often accept as inevitable the pain of hard choices during a recession. However, the annual impact of modest deposits in the good times will be significantly outweighed by preserving the services New Yorkers need during times of economic hardship.

***

Andrew Rein is president of Citizens Budget Commission. On Twitter @cbcny.

***

Have an op-ed idea or submission for Gotham Gazette? Email This email address is being protected from spambots. You need JavaScript enabled to view it.

For Racial Justice, Cuomo and Legislative Leaders Must Pass Marijuana Legalization

(photo: Governor's Office)

We are days away from the end of the legislative session and among the many important issues Governor Cuomo and New York legislators have left to accomplish is addressing the racially-biased and unjust enforcement of marijuana prohibition in our state.

The Marijuana Regulation & Taxation Act (MRTA), currently being considered by New York lawmakers, is one of the clearest pathways toward reducing racism in New York. In the last 20 years our beloved state has earned the dubious distinction of becoming the marijuana arrest capital of the country, with more than 800,000 arrests made just for possession of small amounts.

Nearly 80% of those arrested have been people of color, even though drug use occurs at similar rates across racial and ethnic groups.

These arrests are not a trivial matter. They involve being handcuffed, placed in a police car, taken to a police station, fingerprinted, photographed, possibly being held in jail for up to 24 hours while awaiting arraignment before a judge, appearing in court several times over the course of months, and potentially concluding with the imposition of a permanent criminal record that can easily be found online by employers, landlords, schools, credit agencies, and banks.

New Yorkers who are arrested often face consequences that can make it difficult to get and keep a job, maintain a professional license, obtain educational loans, secure housing, or even keep custody of a child. This is all for something that is now legal in 10 states and the District of Columbia, and that white people do for the most part without consequences nationwide.

If you are among the many who believe legalization isn’t necessary, believing New York’s decriminalization law protects people of color from law enforcement harassment, let me share the reality of what happens in our communities.

While it is currently illegal to sell marijuana, you are not technically supposed to get arrested for possession of small amounts. But New York’s decriminalization law, which we’ve had for 40 years, is failing. More than 60 people on average are still arrested every day for marijuana possession in the state. These arrests have been largely justified by a loophole allowing police officers to distinguish between public and private personal possession. Because possession in “public view” remains a crime—and the fact that there is pervasive and racially-biased over-policing of communities of color—mass arrests continue.

The MRTA will not only put an end to these racist police practices, but will create a responsible and well-regulated industry that will better restrict minors’ access to marijuana. It will also generate millions in tax revenue to bolster the state economy and support the communities that have been most harmed by marijuana prohibition.

The bill additionally works to address some of the unjust consequences of marijuana prohibition by creating a process for both the reclassification of past convictions related to marijuana and for the resentencing of currently incarcerated individuals who are serving time due to a marijuana-related offense. This provision of the legislation will remove significant barriers that New Yorkers face in the wake of a marijuana conviction and allow them to fully participate in society without the devastating toll of collateral consequences.

New Yorkers can feel assured knowing that the sky did not fall in states like Washington, Colorado, Oregon, and Alaska that have legalized the adult use of marijuana. Use by minors has not gone up, and there has been no increase in driving under the influence. We have the major benefit of learning from hurdles these pioneering states had to overcome, and incorporating lessons learned.

The drug war has left a lasting impact on generations of New Yorkers, particularly harmful for people of color. State resources that could benefit our communities are instead being used to perpetuate wasteful and damaging prohibitionist policies that have not been successful in curbing use, increasing public health, or benefitting communities.

The MRTA will not only earn the state billions in revenue, but will reinvest some of this money back into the communities that have been most harmed with adult education services, job training, the expansion of afterschool programs, re-entry services, and other community-centered projects. Money will also be directed toward public schools as well as drug treatment programs and public education campaigns geared toward reducing opioid overdoses and saving lives. It is a win all around.

It is time to stop the ineffective, racially-biased, and unjust enforcement of marijuana prohibition and to create a new, well-regulated, and inclusive marijuana industry that is rooted in racial and economic justice. If Governor Cuomo and New York legislators are really interested in curbing racism in our state, they will pass the Marijuana Regulation & Taxation Act this legislative session.

***

L. Joy Williams is the President of the Brooklyn NAACP. On Twitter @LJoyWilliams.

***

Have an op-ed idea or submission for Gotham Gazette? Email This email address is being protected from spambots. You need JavaScript enabled to view it.

Automatic Voter Registration is Good for Service Members, Veterans, and All New Yorkers

(photo: Ed Reed/Mayoral Photography Office)

When I reported to my first duty as a Junior Officer of the United States Navy, my senior officer told me: “Your job is to take care of your people. Your people will take care of the ship.” This advice holds true outside the service: take care of your people, and they will take care of their family, their community, and their country.

It holds especially true when it comes to New York’s more than one million eligible voters who are not registered to vote. As a member of the armed services and as a veteran I’ve faced the burden of having to register to vote in multiple states, particularly here in New York, where the registration process is cumbersome, time-consuming, and inefficient. Now imagine if our state government systems actually worked together to reduce the bureaucracy for New Yorkers trying to navigate them. One significant way the U.S., and New York in particular, can make sure all can take part in the democratic process is by passing Automatic Voter Registration (AVR).

The idea is simple: instead of placing the onus of registration on individuals, eligible voters are automatically registered to vote by the state when they interact with a government agency.

Under New York’s current system, when someone moves within the state, they’re required to take the proactive step of updating their registration information. With AVR, the process would be made seamless. For example, if applying for a driver’s license or registering for classes, your info would be transmitted to the Board of Elections without any further action required on your part.

Critics argue that voters should take some responsibility for their registration but making it easier to register and preventing people from having to chase bureaucracy is a small price to pay, particularly for those who have borne the burden of war. The fact is, registration rates among active service members are consistently lower than among Americans generally. This is especially true in New York, which has the fifth largest veteran population of any state and is saddled with chronically low rates of registration.

For mobile or hard-to-reach populations like service members, as well as low income communities and communities of color, AVR would prove particularly effective, allowing your registration to follow you instead of vice versa. That also goes for military veterans suffering from physical or mental illness.

Beyond making the experience easier, AVR would also bring our agencies into the digital age. Imagine if our state government systems actually worked together to reduce bureaucratic wrangling that has come to define New York’s electoral process.

My career after the military has involved working with clients on digital transformations. I have observed organizations that I work with benefit from taking down the walls that separate their information systems. AVR is no different in the level of efficiency it would generate.

By now many of us are familiar with the 2016 incident in which the New York City Board of Elections erased 200,000 voters from the rolls. The reason for incidents like this is that our agencies tend to be siloed. New York requires residents to go online and fill out a separate form to register to vote, despite the fact that numerous agencies already collect the necessary information required to fill out voting forms.

AVR would break down these walls. A visit to the DMV or a Medicaid office would enable those agencies to electronically transmit your registration information to the BOE in a form that can be read by a computerized registrant list – saving time and money.

One study found that online and automated voter registrations saved Maricopa County, Arizona over $450,000 in 2008. It cost 33 cents to manually process an electronic application and an average of 3 cents to use a partially automated review process, compared with 83 cents for processing a paper registration form.

We have the opportunity to facilitate voter registration and make the process simpler while ridding our voter rolls of duplicates and eliminating incorrect and out-of-date addresses.

That’s why I went to Albany during a recent legislative hearing to share my experience.

Maintaining and protecting democracy requires more than service-men and -women going in harm’s way. It also requires providing citizens with not only the liberty, but the realistic ability, to exercise the right to vote and participate in the democratic dialogue.

We need to take care of our people by making it easier for all eligible voters so they can take care of our ship - this country. To ensure the full enjoyment of the rights for which my fellow veterans and I fought, and our current service-members continue to fight, the New York State Legislature should pass automatic voter registration this session.

***

Dolpha Freeman is a former U.S. Naval Officer and graduate of the U.S. Naval Academy. Dolpha currently works in a digital transformation consulting practice and resides in the Hudson Valley.

***

Have an op-ed idea or submission for Gotham Gazette? Email This email address is being protected from spambots. You need JavaScript enabled to view it.

Penn Station Needs a Complete Overhaul. We Must Start Now.

(photo: Don Pollard/Governor's Office)

For decades, Penn Station has wreaked havoc on the lives of hardworking New Yorkers, and seriously stained our city’s reputation as a global cultural and economic hub. But all hope is not lost; the door is opening for significant improvements to finally be made.

We’re now just a few short years away from the opening of Moynihan Train Hall and East Side Access. These two important projects, which will temporarily reduce the number of passengers travelling through Penn, present a brief window for significant station improvements.

Transit experts have spoken extensively about the serious safety concerns within Penn Station—from overcrowded platforms, to a lack of accessible exits and signage on what to do in the event of an emergency. The recent announcement of an overhaul of the LIRR corridor and 7th Avenue entrance is a good first step, but there are a host of other improvements that should also be considered.

And beyond safety, it’s a matter of dignity, utility, and a vision for the future of the city we want to live in. Commuters shouldn’t have to settle with what we have.

They’ve seen a variety of great layouts and amenities – that work, by the way – at Washington D.C.’s Union Station, Boston’s South Station, and transit hubs overseas.

We need to look at Penn Station and the surrounding area in Midtown West comprehensively to solve this problem in a way that makes sense for commuters, residents, workers nearby, and New York as a whole.

Leading architects and designers have already created many informed and inspiring renderings and plans for what a new Penn Station could look like. While these designs are all different, they largely address the core issues of overcrowding, platform capacity, and accessibility.

Let’s be clear, Penn Station is not the way it is because of a lack of technical or planning knowhow.

It’s a political problem that can only be solved by bold, willing leadership that is committed to seeing this through from beginning to end.

It also means having a frank conversation about the future of Madison Square Garden, which sits atop the station—severely limiting natural light, air, and the ability to expand capacity.

For our leaders, fixing Penn Station must come down to our values as New Yorkers. We allowed our subways to enter a state of extreme disrepair that forces commuters onto already packed and delayed trains, or for some, abandoning the system all together. Deadlocked street traffic and slow bus speeds are the direct result of the failure to fix what’s going on underground. This is what happens when problems are left to fester.

If leaders don’t believe Penn Station is worth the investment of taxpayer dollars, they should be upfront about that and let voters know where they stand. If it’s a core issue they support, elected leaders should make it clear by calling for the creation of a Penn Station task force that would convene this year.

This task force should resemble the model used to evaluate congestion pricing and it should offer tangible next steps for a comprehensive fix—not a patchwork solution.

2019 has already been a unique year in Albany, with 39 new faces between the Assembly and Senate. Long Island was particularly active during the campaign season with several incumbents who were defeated—and is home to a major constituency that relies on Penn Station. As we rebuild our airports at JFK and LaGuardia and inaugurate new bridges like the Mario M. Cuomo Bridge spanning the Hudson, Penn Station must be our next big fix.

If we don’t get to work to fix Penn Station now, it won’t ever happen. It’s time to act.

***

State Senator Brad Hoylman represents parts of Manhattan, including Penn Station. On Twitter @BradHoylman.

***

Have an op-ed idea or submission for Gotham Gazette? Email This email address is being protected from spambots. You need JavaScript enabled to view it.

Missing Pieces of the Criminal Justice Reform Conversation

(photo: Spencer T Tucker/City Council)

Many justice reformers welcome increased political support for constructive systemic changes. New York state government, for example, recently enacted reforms aimed at restricting the use of cash bail and reducing misdemeanor arrests. Many Democratic presidential candidates pointedly decry mass incarceration and our "broken" criminal justice system.

The most positive feature of this shifting landscape is the moral concern that it reflects, the relatively new recognition among pundits, politicians, and broader public that our criminal justice system is marked by a stark racial bias and that it undeniably violates our nation's core principle of, as Thomas Jefferson put it, providing "equal and exact justice" for all people.

What's missing, though, is certainty that all the attention will lead to meaningful changes in on-the-ground practices.

For instance, New York’s bail law includes significant exceptions regarding who can benefit from its provisions: judges can still set cash bail for New Yorkers with open warrants and with failures to appear in their histories. That’s many thousands of people.

Plus, and this point applies to all the reforms enacted, the agencies mainly responsible for the system’s current abuses, district attorneys and police, are still in power. They are in charge of implementing the changes and have ways at their disposal, overcharging being the most handy, to undermine them if they so choose.

Also, none of the Democratic presidential candidates who engage in indignant rhetoric on the issue have presented the kind of specific steps needed to reverse mass incarceration and to end systemic racism. We know from research and experience that the typical proposals that they and other mainstream politicians offer — body cameras, community policing, increased diversity, even marijuana legalization — will not make meaningful differences in current toxic practices. Jurisdictions that have enacted these changes still lock up far too many Americans, a disproportionate number of whom are Americans of color.

What's missing are policy reforms, proposed or enacted, that lead to institutional changes that are fundamental -- could say radical, in the sense that they address the "root" of the problem -- and significantly cut into the currently unchecked power of police and prosecutors.

One such step would involve repealing mandatory sentencing laws. It was the notorious Rockefeller Drug Laws -- enacted in New York in 1973, requiring a minimum prison term of 15 years (up to life) for the sale of 1 ounce or possession of 2 ounces of a hard drug -- that jump started the extraordinary expansion in imprisonment in the United States that we dub the "mass incarceration" movement. Eventually every state in the country and the federal government passed mandatory sentencing statutes, and the number of incarcerated Americans went from about 300,000 in the early 1970s to about 2.4 million today.

Abolishing these laws and restoring judicial discretion would substantially reduce the power of district attorneys to control case outcomes. Inevitably, courts would imprison a much smaller proportion of the people who the police funnel into the system.

Police practices are the most compelling factor driving the system's stark racial bias, especially in our nation's large cities. Jails hold mainly black and brown people because police arrest mainly black and brown people. Visit our city's arraignment courts where arrests are processed and a white defendant is a rare sight. On Rikers Island over 90% of the people locked up are non-white, there for two main reasons: they are too poor to afford bail and a NYPD officer has arrested them. Simply put, we cannot uproot the racism plaguing our justice system without drastically changing deeply discriminatory police practices.

Abusive police practices are firmly entrenched and long-standing -- New York City’s early civic leaders, for example, established the NYPD in 1845, expecting it to control and contain two unruly groups new to the city: recent Irish immigrants and free black people ("free" because the state abolished slavery in 1827). Modest modifications, like issuing criminal summonses instead of arresting people and implicit bias training, won't do. The changes must cut into the police's absolute power, which, after all, corrupts absolutely, to end persistent ways officers violate certain Americans' rights and well-being.

Specific examples include: ending quotas that pressure officers to make unnecessary arrests and stopping "broken windows" tactics targeting poor people of color for infractions virtually ignored in white communities; eliminating arenas of responsibility police now have that are better addressed by social services like school safety, sex work, homelessness, and mental health; and substantially cutting police budgets and personnel.

In September 1955, after learning that an all-white Mississippi jury acquitted the men who tortured and killed Emmett Till, Chester Himes, a novelist based in Harlem, commented: "The real horror comes when your dead brain must face the fact that we as a nation don't want it to stop. If we wanted to, we would." Now, as was true 64 years ago when Till's murderers went free, no mainstream politician will back the "radical" measures needed to end biased and abusive policing. Few, if any, will call for repealing mandatory sentencing laws -- all too electorally risky.

But if our leaders want to move beyond hand-ringing expressions of moral concern about our justice system's inhumane practices, if they want to fulfill our nation's founding "justice for all" promise, they, or, perhaps, even just one of them, will come forward and, in response to Mr. Himes' plaint, state: "Now we will."

***

Bob Gangi is the director of the Police Reform Organizing Project (PROP). On Twitter @GangiFromPROP.

***

Have an op-ed idea or submission for Gotham Gazette? Email This email address is being protected from spambots. You need JavaScript enabled to view it.

How to Address Anti-Semitism in New York City, and Beyond

(photo: Ed Reed and Paige Polk/Mayoral Photography Office)

Like so many Jews, we are horrified and dismayed at the recent attacks on visibly Jewish people in New York City, in particular Hasidic and Haredi men. Anti-Semitic violence is on the upswing in the U.S. and in our city.

The NYPD reported 145 hate crimes between January and April; 82 of those incidents, 57%, were anti-Jewish. Hate crimes in general rose 67% in the first quarter of this year, and anti-Semitic hate crimes in particular increased by 82% over a similar period last year. White Christian nationalist violence, stoked by the election of Donald Trump, is on the rise — from New Zealand to New York.

This trend is unacceptable, but we can’t arrest or guard our way to real safety — the solution lies with communities.

Between attacks on Jewish people on the streets of New York, and the murders of Jews in our synagogues in Pittsburgh and Poway, we know that we need to address security concerns in a new way. So we understand why 39 members of the New York City Council, led by members of the Council’s Jewish Caucus, recently signed a letter urging Mayor de Blasio to use city funds to pay for armed, off-duty NYPD officers to guard houses of worship.

We all want to feel safe, especially in our churches, synagogues, and mosques, but city-funded armed police guards actually make some of us less safe, and cause many Jewish people of color, especially black Jews, to feel unwelcome in Jewish institutions. The truth is, policing cannot solve our problems — we will never arrest our way out of anti-Semitism.

As the city struggles to find money to deal with crises in homelessness, public housing, education, and more, paying cops to be security guards represents a back-door source of additional funding for the NYPD. This only escalates New York’s dramatic over-investment in the security state, instead of investing in our future.

We refuse to downplay the profound threat of anti-Semitic violence, or to dismiss the real fear and pain our community feels in this moment; yet we believe that there is a better way for the Jewish community to protect itself: by preventing hate violence in the first place. Armed guards are not a panacea — data show that the presence of police can actually attract shooters, and that, too often, police officers shoot bystanders in response to an attack, increasing the bloodshed rather than preventing it. In addition, arresting a suspect after an incident does not address the underlying tensions and ideologies that lead to hate violence; and increased penalties for hate crimes are unlikely to deter assailants from committing acts of violence.

Further, because communities of color are systematically overpoliced, a response to hate violence that emphasizes policing will inevitably have a negative impact on those communities, and reinforce the racist narrative that black people are more responsible for anti-Semitism than white Christians and other groups. (According to the NYPD’s own statistics, of the 69 anti-Jewish hate crimes in 2018 that resulted in an arrest, 40 of the alleged perpetrators were white, while 25 were black; nationally, from 2009–2018, 73% of all fatalities by violent extremists were caused by right wing actors.)

If we want to focus on prevention in New York City, the best approach is the Hate Violence Prevention Initiative that a coalition of Jewish, Arab, LGBTQ, and immigrant community organizations have presented to the New York City Council. The communities that these groups represent share a mutual interest in standing up to hate-motivated violence and white nationalism. All of us understand that hate violence and bias incidents can only be prevented in local communities, by local communities — not by police or prosecutors.

We need approaches that prevent violence through education and community-building, interrupt violence through community-based upstander/bystander trainings and rapid response at the local level, and repair damage through restorative justice, counseling, and peer-support. We oppose “zero tolerance” policies — an approach that is geared toward impressive sound bites, not effective hate violence reduction.

The Hate Violence Prevention Initiative will fund preventative education, restorative justice, upstander/bystander intervention trainings, and rapid response within communities when an incident has occurred.

"As a Jew of color, the initiative's focus on restorative justice also works better to provide safety for my community and all Jews, not only white Jews. A police presence outside a house of worship puts black Jews in danger." —co-author Arielle Korman

If we are serious about confronting the rise in hate crimes, we need an approach led by organizations in affected communities that is designed to confront the white supremacist ideology and anti-Semitic ideas fueling those crimes, and to ease the intra-communal tensions that surface them.

Up until now, the city has profoundly under-funded this type of approach. The dominant response to all hate violence incidents has been to call for increased policing and the filing of hate-crimes charges. We can do better. The recent arrest of a 12-year-old for chalking swastikas on a school playground demonstrates just how far we are from a targeted and proportional response that is likely to reduce hate violence in the future.

We find the rise in attacks on Jews terrifying but we know we’re not alone. We are inspired by the outpouring of care and solidarity from our neighbors when incidents of hate violence occur, and we are proud of the ways that many Jews have shown up for others in these difficult times.

For better or for worse, many of New York’s communities have a stake in standing up to right-wing, white nationalist ideology and the violence that it inspires. We believe that the only effective response to hate violence is one that cuts these ideas off at the root, and that binds together all of the communities impacted by bigotry — not one that pits us against each other.

***

Martha A. Ackelsberg is the William R. Kenan Jr. Professor Emerita of Government and Professor Emerita of the Study of Women & Gender, an author, and a member leader at Jews For Racial & Economic Justice (JFREJ). Arielle Korman is a graduate student at Columbia University, a cultural organizer, a member leader at JFREJ, and a co-founder of JFREJ’s Jews of Color Torah Academy.

***

Have an op-ed idea or submission for Gotham Gazette? Email This email address is being protected from spambots. You need JavaScript enabled to view it.

Stop the Rat Takeover with the Humble Brown Bin

(photo: Ed Reed/Mayoral Photography Office)

When the New York Times announced that Rats Are Taking Over New York City, the widely-shared article and subsequent discussion overlooked one obvious remedy: reboot New York City’s stalled, neglected Organics Collection Program, and use it to take away a primary food source for rats near residential buildings.

Organics collection was introduced in New York City in 2013 and later incorporated into Mayor de Blasio’s OneNYC plan, which includes an ambitious “zero waste” goal: that the city will send nothing to landfills by 2030.

For residents in all of Manhattan and many neighborhoods in other boroughs, the city provides free plastic bins for curbside collection of organics: food and yard waste that make up 34% of all residential waste according to a 2017 New York City Department of Sanitation (DSNY) study cited at a 2018 City Council hearing. However, the program has stalled -– the city missed its planned deadline of having organics collection in every neighborhood by the end of 2018.

In the areas where the program currently operates, less than 11% of organic waste makes it into the brown bins. So most of New York City’s food waste winds up mixed in with other trash left in plastic bags on sidewalks overnight, and provides a ready food source for rats right next to residential buildings.

Rats can tote a slice of pizza down stairs or climb a subway pole, but they’ll never open the latch on top of a brown organics bin set out for curbside pickup. If New Yorkers could be persuaded (or mandated) to put all their household food waste into these city-provided bins, rats would be locked out of their current all-night buffet on our sidewalks.

In May 2018 after the DSNY froze the expansion of the organics collection program, Commissioner Kathryn Garcia promised “intensive outreach” to “grow participation” in areas where the program exists, but it is hard to find evidence of any such outreach.

The building where I live has been using a city organics bin for our food waste since the program began, but I’ve watched every other building on our block stop participating in the program. Here in Park Slope, Brooklyn, I’ve never seen any sort of outreach from the city to encourage participation, and in the last two years it has become more difficult to participate. DSNY used to drop off replacements for lost bins, but now it requires residents to drive to its office to pick up a new one. DSNY has also reduced the organics pickup schedule to one day per week instead of two.

The building where I live has been using a city organics bin for our food waste since the program began, but I’ve watched every other building on our block stop participating in the program. Here in Park Slope, Brooklyn, I’ve never seen any sort of outreach from the city to encourage participation, and in the last two years it has become more difficult to participate. DSNY used to drop off replacements for lost bins, but now it requires residents to drive to its office to pick up a new one. DSNY has also reduced the organics pickup schedule to one day per week instead of two.

The city missed an opportunity in not connecting organics collection to the rat problem. “Zero Waste” by 2030 has the same flaw as “Vision Zero” for traffic deaths -– it’s hard to see it as achievable, or as anything more than a pie-in-the-sky promise. “Separate all your garbage now and we’ll fix climate change in some future mayor’s term” is not nearly as compelling as “Put your food waste in this bin now so you don’t have to dodge rats when you walk out your front door.”

When the city gets complaints about rats in an area, in addition to putting out poison and adding a $7,000 solar-powered trash can to a local park, city workers also should help every residence and business in the area start using organics bins. Some advertising and hands-on assistance would make a huge difference, and make long-term environmental goals possible by focusing on New Yorkers’ quality of life in the short term.

Elected officials are often eager to declare an emergency and announce a quick, expensive response when a long-standing problem pops up in the news. Mayor de Blasio did this in 2017 when he proposed a $32 million “Rat Reduction Plan,” which included a bill to require some buildings to put out their trash at 4 a.m. (that bill never passed). Statistics cited in the Times story show the plan didn’t lead to long-term reductions. Persistent problems demand persistent effort and consistent messaging, especially when the solution requires millions of people to change their daily habits.

When every building in New York City has an organics bin, and every New Yorker has heard how this program can improve their quality of life, then we’ll be a step closer to a sustainable future, and also less likely to step on a rat when we walk down the sidewalk.

***

Tony Melone is a freelance musician and volunteer activist in Brooklyn. On Twitter @tonymelone.

***

Have an op-ed idea or submission for Gotham Gazette? Email This email address is being protected from spambots. You need JavaScript enabled to view it.

Ending Health Disparities That Disproportionately Impact New Yorkers of Color

Council Member Carlina Rivera, left, one of the co-authors (photo: John McCarten/City Council)

New York City is one of the largest, most diverse, and advanced cities in the country – in fact, New Yorkers are living one-and-a-half years longer than a decade ago and nearly nine years longer than 25 years ago. Yet behind that positive sheen lies a shameful truth – our city persistently falls short in health outcomes for people of color.

As a New York City lawmaker chairing the committee that oversees our city’s largest public health system and as the founder and leader of the city’s largest physician-led nonprofit health care network, we are troubled that despite economic and technological leadership, our city continues to fall short on health basics.

Persistent health disparities are spread across all five of New York City’s boroughs, most noticeably in communities of color. So, with another Minority Health Month in the rear-view mirror, we are hoping to spur solutions and bring much needed attention to these crises beyond just one month. Whether it is tackling the epidemic of diabetes, maternal mortality rates, or depression and suicides, we can no longer take on these issues without highlighting the disparate rates at which these medical issues affect New Yorkers of color.

And the solutions to these challenges can’t just come from one sector. We need policymakers, community doctors on the front lines, and healthcare experts to all fight together for essential access to preventive care, increasing basic health education and literacy, and addressing the social determinants of health.

Our urban reality is stark: compared to their white neighbors, Latinx women are 60% more likely to be diagnosed with cervical cancer and are 70% more likely to receive late or no prenatal care; Asian-Americans are 30% more likely to be diagnosed with tuberculosis and 10% more likely to be diagnosed with diabetes; and African-Americans are 60% more likely to experience a stroke that could end in them becoming permanently disabled.

In addition, key survey findings in SOMOS’s State of Latino Health report highlighted a series of health disparities Latino New Yorkers struggle with every day. For example, 33 percent of Latinos don’t think people in their community get the health care they need, and 61 percent of providers think that Latinos face unique barriers that keep them from accessing health services.

Many of these conditions are exacerbated by what are known as social determinants of health, or more simply, the conditions in which New Yorkers live. These social determinants are attached to economic stability, education level, social and community context, health and health care; and neighborhood and built environment. And, every single one of these factors can determine a wide range of health risk outcomes.

Overall, New Yorkers who live in poverty and cultural isolation, including immigrant and first-generation New Yorkers, live underserved and in a political climate hostile to the historically disenfranchised. Put simply, this crisis is decades in the making, which is why the City Council Committee on Hospitals has been dedicated to examining these issues at our hearings and advocating for solutions from our city’s biggest medical providers.

We must improve health literacy through building awareness – and use cutting edge technology to meet diverse New Yorkers where they live and how they receive information. New York City has more languages and dialects than the United Nations, and we are stronger and more unique for it – yet in many communities our access to internet services is far too low. We need to translate simple, effective health literacy messages from nutrition and exercise to smoking cessation in order to better reach more families and employ digital and handheld technology to carry the message.

We must make sure nutrition and healthy eating are no longer the purview of elites. It’s worth repeating that farmers markets and supermarkets that specialize in natural, low-calorie, low-sugar, low-fat foods are economically far out of reach for far too many neighborhoods. Lowering food costs and making healthy food far more accessible and culturally relatable can make a huge difference in basic health for hundreds of thousands of New Yorkers who want to eat healthily but simply can’t afford it or aren’t exposed to it. And we know that local vendors who partake in farmers’ markets and sell to health food markets would like to reach more consumers.

Together, we are pursuing a collaborative agenda defined by our partnership, expertise and unique lived realities.

***

City Council Member Carlina Rivera represents the 2nd district, which includes portions of the Lower East Side in Manhattan, is Chair of the Council’s Committee on Hospitals and Co-Chair of the Council's Women’s Caucus. Dr. Ramon Tallaj is Chairman of SOMOS, a non-profit, physician-led network of more than 2,000 health care providers serving over 700,000 Medicaid beneficiaries in New York City, with providers delivering culturally competent care to patients in some of New York City’s most vulnerable populations.

***

Have an op-ed idea or submission for Gotham Gazette? Email This email address is being protected from spambots. You need JavaScript enabled to view it.

Our Work on Public Campaign Financing is Not Done

the authors: Assemblymember Niou, center, & Senator Ramos, left (photo: @NYCComptroller)

We’ve got a big money problem here in New York, and we hear loud and clear the New Yorkers who are calling for a small donor solution in the form of public financing of elections.

Public financing became a top issue in state budget negotiations earlier this year because of public demand. The plan for a commission to now determine the parameters of public financing of elections was placed in a large budget bill in the final hours of budget negotiations, making it nearly impossible to oppose as legislators.

But we must introduce and move public financing of elections bills this legislative session -- before it ends June 19 -- to fix, or overturn, a weak commission result. We’re committed to ensuring that we end this year with a strong public financing program in New York, whether via commission, legislation, or a combination of both.

It’s important to push this issue ahead and not simply allow the commission to unfold without additional legislation for several reasons.

As women of color and as elected leaders representing people from all walks of life, we are here to bring change and shift power away from big donors and to the people of New York.

Our elections are currently dominated by a tiny number of big donors. According to the Brennan Center for Justice, just 100 donors outspent all the 137,000 small donors combined last year. It’s time for regular constituents to get their say through a 6-to-1 small donor match, lifting the voices of everyday New Yorkers and fundamentally changing the way politicians fundraise by allowing them to focus on those who may only give $20.

Those who oppose reform point to the price tag with a high estimate of $100 million per year (a small fraction of one percent of our state’s budget) as an excuse to avoid changing the status quo. They say we can’t afford it. You know what costs more? Corruption.

When elected leaders are forced to spend their time rubbing shoulders with big donors—who tend to be predominantly corporate donors—we end up with expensive, unnecessary, out-of-touch policies that hurt the rest of us. We also shut out people with a desire to serve their communities but without connections to big donors from running for office. These systematic barriers block women and people of color—in particular women of color—from running and winning public office.

Following damaging decisions by the Supreme Court that now allow unlimited money into our elections, public financing of elections is the only real way to counter the corrosive influence of super PACs—and we have a chance to show the nation how to get it done.

In Connecticut, after a small donor public financing system was put in place, lawmakers moved forward policies to end corporate giveaways and pushed ahead issues that are meaningful to communities of color and other underrepresented communities.

Once public financing was in place, leaders passed mandatory paid sick days, increased the minimum wage, instituted in-state tuition for undocumented students, and helped low-income and working individuals and families by adopting an Earned Income Tax Credit.

In another illustrative example, they also ended the practice of returning unclaimed bottle deposits to the beverage industry. The influence of beer and soda distributors long kept this giveaway worth up to $24 million annually in place. Now the money can be redirected to important public programs.

To ensure a similar result—a democracy that is not beholden to wealthy special interests and instead is responsive to the needs of constituents—in New York, we must ensure a strong Public Financing and Elections Commission that gets to work soon with diverse and credible commissioners to hold transparent proceedings with ample room for public input.

As lawmakers, we have to be prepared for the possibility of a weak commission result. Our responsibility does not end with appointing commissioners. It’s our duty to ensure a strong public financing program, and that means having legislation ready should we need to improve upon the commission’s recommendations.

Our mission is clear. We must deliver a strong small donor public financing program by the end of the year to shift power to the people of New York and away from big donors. We’ve come too far to settle for anything less.

***

State Senator Jessica Ramos represents parts of Queens. Assemblymember Yuh-Line Niou represents parts of Manhattan. On Twitter @jessicaramos & @yuhline.

***

Have an op-ed idea or submission for Gotham Gazette? Email This email address is being protected from spambots. You need JavaScript enabled to view it.