The Mayor's Mistaken Attempt to Supersize Buildings

(Credit: Michael Appleton/Mayoral Photography Office)

Nearly every day it seems, a new record is broken for a tallest new residential structure in our city. Whether it is Downtown Brooklyn’s first 1,000+ foot tall tower, Queens’ tallest tower in Long Island City, or the 1,550 foot tall West 57 Street residential tower that will soon rise higher than the top floor of One World Trade Center, residential building in New York City is reaching new heights.

But for Mayor de Blasio and the real estate industry, even these record-breaking heights are not enough. They are advocating for repealing a 60-year-old state law, which, while capping the size of residential developments in New York City, is still so generous as to allow the unprecedented giants going up now.

If the mayor and the real estate industry have their way, the sky could literally be the limit for residential high-rises in New York City. And not just in Midtown or the Financial District, but residential neighborhoods like the Upper East Side and Upper West Side, Greenwich Village, and various parts of Brooklyn and Queens, where current rules limit new residential development to at or near the cap imposed by state law.

The possibility is more than theoretical. Two years ago proponents of lifting the cap came close to getting the State Legislature to do so. This year the State Senate pushed for the measure to be included in the state budget, but the Assembly ultimately did not go along with it (though the cap removal definitely has its proponents in the Assembly majority). Most observers expect the supporters of lifting the cap to push the measure again before the state legislative session ends in June, possibly as part of the “big ugly” – the annual package of often unrelated and controversial measures passed in the final hours of legislative session, with little public notice or input.

With all the problems facing New York City right now, from dysfunctional subways to crumbling public housing to crippling congestion, why is this an issue the mayor has chosen to take on?

Mayor de Blasio and some of the proponents of lifting the cap claim it’s necessary to build affordable housing. But not because they want affordable housing developments that exceed the current record-breaking heights. Because they want to allow real estate developers to build vastly larger for-profit, luxury housing developments. In return, they will require them to attach a comparatively small amount of affordable housing to the development.

This is a false dichotomy that the real estate industry has promulgated and the mayor has endorsed – that the best and, in many cases, only way to get new affordable housing out of for-profit developers across the city is by supersizing the amount of luxury, market-rate housing they can build, and then attaching these smaller amounts of affordable housing to it.

It’s due to this approach that communities throughout New York City have opposed the mayor’s rezoning plans – both because they would destroy the scale and character of their neighborhoods, and because under the guise of introducing “affordable housing” (which in many cases is unaffordable to the residents of the neighborhood), vastly increased quantities of very expensive housing is built, which more than counteracts any good done by the relatively small amount of affordable housing created.

Take Greenwich Village and the East Village. These increasingly wealthy neighborhoods with decreasing affordable housing have been begging the mayor to support a zoning plan we have proposed that would allow modest increases in the allowable size of developments as a condition for creating or preserving affordable housing. The mayor has adamantly opposed the plan, saying he would only be willing to consider the kind of massive increases in the allowable size of residential development that would bump up against the current state cap, to say nothing of destroying the character of these human-scaled neighborhoods.

Don’t let the mayor or Big Real Estate fool you. The state cap on the size of New York City residential buildings is not limiting anything New Yorkers should be worried about. The only thing it’s limiting is the already astronomical profits of developers, and the ambitions of some politicians to increase them even further.

***

Andrew Berman is Executive Director of Greenwich Village Society for Historic Preservation. On Twitter @GVSHP.

***

Have an op-ed idea or submission for Gotham Gazette? Email This email address is being protected from spambots. You need JavaScript enabled to view it.

The Great Select Bus Service Conspiracy: Part III

(photo: MTA/Patrick Cashin)

This is part three of a three-part series

Previously discussed: the promises and the reality, the difference between bus travel time and passenger travel time, who benefits and who is hurt by SBS, how the mayor, MTA and DOT mislead, the true costs of SBS (part one); the denigration of local bus service, problems with enforcement, other SBS problems, negative effects on traffic and local businesses and how public participation is inadequate (part two).

Not a Cure-All

SBS is not the cure-all for local bus service problems as purported to be. Some SBS routes do not even make sense. In one case, there is a nearby unused rail line that could be reactivated at a fraction of the cost of constructing a new subway line without disrupting traffic and local businesses as SBS does. Yet it was never considered as an alternative to the Woodhaven Boulevard SBS.

The MTA and DOT want to spend $2 billion on SBS over the next ten years, but will not alter, add or extend existing bus routes to fill transit deserts. Some have been indirect or outdated for over 70 years. The MTA claims it would cost too much to increase service because they refuse to consider the resulting additional ridership from better service. They have rejected route improvements with increased annual operating costs of only $50,000.

Instead, they make foolhardy proposals to eliminate bus stops, such as on the Q22 where there is a high elderly population. The MTA suggested those riders use Access-A-Ride instead. Each one of those trips costs the MTA over $50. New bus routes are scheduled only at 30-minute intervals, which the MTA insists is sufficient. The actual wait for a bus is often longer. Is it any wonder that these routes are among the most lightly-utilized routes in the system?

Important transfer points are missing from SBS routes. For example, there is no way to transfer between the Q52/53 and the B15 Kennedy Airport route, which is also slated for the SBS treatment. “Dollar vans” continue to illegally compete with MTA buses, draining revenue from the MTA.

There is no desire by the MTA to connect new neighborhoods, thereby really improving mass transit. In most cases, SBS is merely replacing existing Limited Stop routes. The Southern Brooklyn SBS needs to connect Bay Ridge with Gateway Mall and Kennedy Airport, not just replace the B82. Potential economic benefits of such new routings are ignored. SBS construction costs (if applicable), operating costs, and ridership are the only variables considered.

How does the mayor know that 21 additional routes will be needed in the next ten years even before any SBS meetings are held? Why aren’t other solutions being discussed or analyzed? Perhaps routes need to be altered or added, more short services need to be provided or a zone express would make more sense than SBS. A short service does not operate for the entire length of the route. A zone express is a bus that picks up passengers bound for a single destination such as a major subway stop until it is full and then operates non-stop the rest of the way.

Can SBS Work?

Yes, if it is done correctly.

By imposing a deadline on DOT for 20 routes by the end of 2017, the mayor rushed the planning process so that some routes were not properly designed. It is now difficult or impossible for trucks to turn onto the Woodhaven Boulevard service roads, necessitating lengthy detours. SBS is most beneficial on very long routes where the average trip length is much greater than 2.3 miles. On the S79, for example, many riders travel a considerable portion of the route, at least five miles, and some travel ten or more, so many do save time. However, the S79 only includes three SBS features (two is the minimum number required to qualify as an SBS route), exclusive bus lanes (rush hours only), and longer distances between some stops than Limiteds; and more recently, TSM. There is no off-board fare collection, hence no additional enforcement costs, and standard 40-foot buses are used so there are no extra labor or fuel costs.

The effect on other traffic resulting from the bus lanes must also be considered to determine if the benefits afforded bus riders are greater than the harm done to motorists. The S79 Progress Report showed that traffic volumes declined on both Hylan Boulevard and parallel roadways. That is understandable when traffic congestion increases, which it did. That does not indicate a lower demand, but a lengthening of the peak period. We know congestion increased because in one instance the time it took to travel between two points increased by 50 percent from 10 to 15 minutes, but declined to a lesser extent in other instances. DOT explained away the time increase by attributing it to “daily roadway fluctuations.”

Responsible traffic studies do not draw conclusions from just two days, and Mondays and Fridays usually are not studied because they are atypical of weekday travel. If DOT averaged three midweek days before and after implementation and allowed at least a month for drivers to become accustomed to the elimination of traffic lanes, perhaps then it would be clear if the increased travel times were really a result of daily fluctuations or not. DOT, however, is really only interested in the effects on bus riders, not on other traffic.

Other routes may also work fairly well like the Bx6, the Bx12, and the Q70. The M15 works well in the late evenings, providing a quicker alternative than the subway from the southern tip of Manhattan to the Upper East Side.

Proposed routes such as the B82 could work if they connect new neighborhoods. The B44 could have been designed better so that Kingsborough College students were better served and employees of Kings County and Downstate Medical Centers were not so inconvenienced. That, however, would have involved creating or rerouting other bus routes in the area to fill a needed service gap, something the MTA is hesitant to do. It also would have required public hearings. The MTA usually prefers the easy way over the correct way.

B44 SBS ridership south of Avenue X would greatly increase to at least a seated load per bus if a branch to serve Kingsborough Community College were instituted as was first proposed in 2013. No increase in service would be necessary because new riders would ride in the off-peak direction. Presently the 60-foot buses south of Avenue X only carry six or fewer passengers even during rush hours, except for a handful of trips when health care workers are changing shifts.

Both proposals were made to the MTA or DOT and have been dismissed or ignored.

Is SBS worth it?

Consider that a simple state law requiring all non-emergency motor vehicles to give the right of way to buses pulling out of bus stops would save bus passengers more time than SBS because it would apply to all 326 bus routes, not only 17 or 38 SBS routes. It would also save the MTA money by shortening bus travel times. Best of all, it would cost virtually nothing, and would disrupt traffic less than exclusive bus lanes.

The first SBS route began in 2008. Using 2011 as a base year and adding up the riders in the 12 SBS corridors we get 101,455,632 passengers. For 2016, the number is 98,800,534 passengers, or a 2.6% decline, while all local routes (NYCT and MTA Bus) declined by 3.3%. (It should be noted that the Q70 became an SBS route in 2015.)

Ridership on SBS routes declined by 0.86% from 2015 to 2016 while the system in general declined by 1.5%. SBS routes performed slightly better than all local/limited routes but did not reverse the declining trend in bus patronage, one of its goals. The M15 First and Second Avenue route alone lost over 3 million annual passengers between 2012 and 2016, more than the total bus ridership in many cities, and that does not consider the opening of the Second Avenue subway. Many local riders could have just decided that walking is now quicker with less frequent service.

Another possibility is that patronage didn't actually decline on SBS routes but fare evasion on those routes is higher than on routes where you pay on board. The MTA insisted for a long time that a fare-evasion rate of three percent was acceptable and within industry standards. After a newspaper expose, it finally admitted fare evasion on local bus routes was 14 percent and took temporary mitigating actions to reduce it.

Fare evasion rates for SBS are unavailable. The MTA admits that each SBS inspector costs $100,000 per year in salaries and accounts for the biggest ongoing cost. But how much enforcement is there? One daily SBS rider claimed to have seen the Eagle team on the bus only once in the past year. We need to know if fare evasion rates for SBS are higher than on traditional bus routes.

What will happen to all the fare machines, which cost $50,000 each, when they become obsolete in a few years as the MetroCard is replaced with a tap and go system? Is additional investment in these machines worthwhile or should we place a moratorium on creating new SBS routes at least until MetroCard is replaced?

Mayor Bloomberg had suggested that Manhattan’s crosstown routes be free due to the high percentage of those transferring from other buses and subways who have already paid their fare. This would allow all-door entry without the expense of SBS machines and enforcement. The Riders Alliance questioned if it was worth the cost to convert and operate the Q70 (LaGuardia Airport route) to SBS since 80 percent of riders are already paying their fare on the subway and recommended the route be free. A cost-benefit analysis should have been performed in both cases regarding how high the percentage of passengers paying for their trip elsewhere needs to be before it becomes more cost effective to run SBS rather than operate the route for free. Those analyses were not done.

SBS costs are not transparent; benefits are marginal. Passenger travel-time savings, which should be the key metric of SBS improvement, are unavailable. Yet we are asked to embrace SBS without adequate proof it is a success and ignore all negative effects.

What is the driving force behind SBS for state and local officials? Is it that the federal government is paying a portion of the costs and this is regarded as “free money”? And that if New York City doesn’t apply for these funds, another city will? If so, that source may soon dry up. Is the mayor more interested in raising revenue from levying heavy fines while the MTA shoulders most of the enforcement costs? Is the real goal to improve transit or is it just the perception of improved transit?

Summary and Conclusions

SBS is not low-cost and has not been a massive improvement. Don't let the unconditional support by so many groups and officials fool you. SBS may be an appropriate solution in some cases. It is not the solution in every case. Don’t believe the SBS hype. Concentrate on results and actual numbers, not promises and percentages. Look for data other than what is easily accessible from DOT and the MTA. Ask questions and arrive at your own conclusions. Don’t believe 95 percent of bus riders are satisfied with SBS. If that is true, why is ridership on SBS routes generally down? There are reasons why so many are unhappy with SBS and why so many communities vigorously opposed SBS and are opposing planned routes.

According to reliable sources, the proposed B82 SBS was in danger of being scrapped altogether due to heavy opposition and Flatbush Avenue merchants are prepared to lay down in the street when the proposed B41 SBS becomes a serious threat.

To date only the proposed Merrick Boulevard SBS was dropped, and that was early on in the process. It is not as if communities do not want better transit. They just want transit done right without wasting funds unnecessarily and causing unnecessary inconvenience, economic hardship or decreasing safety.

Is it worth spending $2 billion over the next ten years just to save an average SBS passenger only three or four minutes of bus travel time, despite DOT claims of travel time savings up to 20 or 30 percent? True passenger travel-time savings are unknown because of inadequate data. The negatives of SBS must not be ignored. We must insist on adequate public input and data. SBS problems must be corrected; other solutions must be considered. Poorly planned SBS routes are increasing the cost of bus operations without much benefit to the public. There needs to be a moratorium on new SBS routes now.

This is part three of a three-part series. Read part one here and read part two here.

***

Allan Rosen received his Master’s in Urban Planning from Columbia University (with a transportation concentration), planned the massive southwest Brooklyn bus route changes in 1978, was a Director of Bus Planning for MTA New York City Transit, now retired, and wrote a weekly column on transit issues for five years for the blog now called Bklyner.com.

***

Have an op-ed idea or submission for Gotham Gazette? Email This email address is being protected from spambots. You need JavaScript enabled to view it.

City Must Stop Using Incarcerated People as Revenue Source

(Michael Appleton/Mayoral Photography Office)

The City of New York, like many cities and states across the country, profits from people experiencing poverty who come into contact with the criminal justice system. New York imposes a plethora of fees on persons charged with and/or convicted of a crime or minor infraction, ranging from a fee to support the DNA Bank, to an incarceration fee, to a fee for parole or probation.

Among the most egregious of these fees involve phone calls in New York City jails. New York City reaps millions of dollars in profits from people who are in city jails and simply want to make a phone call.

Many of these people have not been convicted of a crime. Nearly 75% of people in New York City jails are held pretrial, many because they were arrested and cannot afford to make bail. Some are in jail serving short sentences for minor misdemeanor offenses. All just want to talk with family, friends, or their attorney.

On Monday, the City Council will take the next step in exploring the opportunity to end this predatory practice when it debates a bill, Intro. 0741, introduced by Speaker Corey Johnson. The bill would put a stop to the City’s practice of using the jail phone as a revenue center. Passing it would be a first and important step toward ending what is truly a tax on justice.

Over the last 30 years, as rates of arrest and incarceration skyrocketed across the country, jurisdictions struggled to pay for the bloated justice system. Cities, counties, and states increasingly tried to generate revenue by imposing fees on people, including children, arrested for and convicted of crimes. In California, the state adds $390 in fees to the $100 fine imposed for running a red light. In Washington State, courts impose an average of $1,347 on every criminal conviction. In New York, people convicted of felonies face mandatory fees of $300; for misdemeanor convictions, the fee is $175.

Although the criminal justice system is a vital government service meant to protect everyone’s public safety, more and more jurisdictions turned toward a “user-funded” system, unfairly demanding that some of the poorest Americans shoulder the burden.

Justice system fees disproportionately harm low-income people and their families who cannot afford to pay them. Communities of color are particularly devastated because they experience higher rates of poverty and over-policing in their communities. It is a burden that is often too heavy to bear. For the millions of people who cannot afford to pay them, outstanding fees trap them in the justice system for prolonged periods, entrenching poverty, exacerbating racial and ethnic disparities, and diminishing trust in government. And, because so many people cannot afford to pay them, criminal justice fees often generate less revenue than expected.

Some local and state governments have gone beyond simply trying to recoup costs through justice system fees and are trying to generate profits by imposing fees on people who are incarcerated, regardless of whether they have been convicted of any crime. In jurisdictions across the country, fees for “services” in jails and prisons (including exorbitant mark-ups on items for sale in the commissary) as well as fees for mail and “video” visitation are routinely imposed. New York City’s phone fee is a prime example of this unjust, discriminatory, and misguided policy.

Like all justice system fees, the phone fee particularly harms the city’s most vulnerable communities. It may also diminish public safety. When people in jail can’t afford to pay for phone calls, they can be cut off from contact with their families. Research shows that regular communication between incarcerated people and their loved ones correlates with lower recidivism and higher opportunity for successful re-entry to society.

We know the phone fee disproportionately harms people experiencing poverty and communities of color and may lead to higher recidivism rates. Yet, New York City government plans to extract millions of dollars next year from families who wish to stay in contact with their loved ones in City jails. Indeed, the mayor’s proposed budget anticipates that the Department of Corrections will collect nearly $6 million in profits from phone calls made by people incarcerated in city jails. But, budget negotiations between the de Blasio administration and the City Council have until the end of June to get it right.

The Council Speaker’s bill would stop the City from profiting from people who have already been targeted and trapped by a system that takes away freedom, dignity, and hope. It would help ensure that people who are incarcerated maintain critical community ties while they are in jail, increasing their opportunity for successful re-entry when they are released. It should be adopted by the Council and signed by the mayor.

***

Joanna Weiss is the Co-Director of the Fines and Fees Justice Center. Brandon J. Holmes is the #CLOSErikers Campaign Coordinator for JustLeadershipUSA. On Twitter @joannagweiss and @BJHolmes_NYC.

***

Have an op-ed idea or submission for Gotham Gazette? Email This email address is being protected from spambots. You need JavaScript enabled to view it.

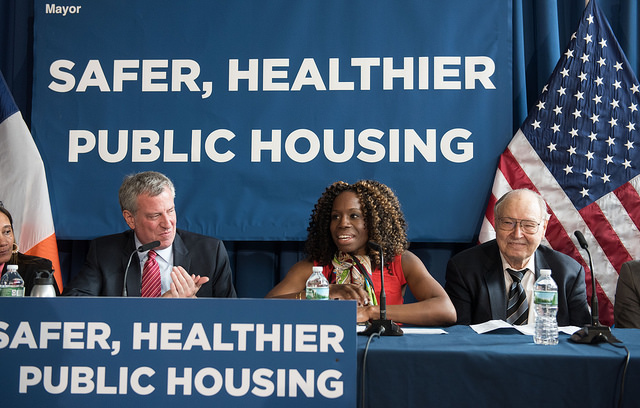

Shola Olatoye Did a Lot of Good for NYCHA

Outgoing NYCHA Chair Olatoye, center (photo: Michael Appleton/Mayor's Office)

As faith leaders in communities with large populations of NYCHA residents, we have witnessed the results of chronic disinvestment in public housing first-hand. NYCHA’s aging buildings are crumbling and many residents are worried about the health and safety of their children, elders, and neighbors.

Since 2001, NYCHA has been shortchanged $3 billion in federal operating and capital funding. NYCHA has been struggling to maintain and repair its aging housing stock for decades. And this is larger than New York City, public housing authorities all over the country are set up to fail, facing gutted budgets and regulatory barriers.

When she took her post as Chair and CEO of NYCHA, Shola Olatoye knew she needed to address these problems, so she worked with communities to make a plan. Under her leadership, we developed NextGeneration NYCHA, a 10-year plan to preserve and protect public housing for current residents as well as the next generation of New Yorkers and beyond. That plan became the road forward to safe, healthy, connected homes and communities for NYCHA residents.

Four years later, as NYCHA has strived to meet the NextGen goals, we have begun to see positive changes for the lives NYCHA residents. Under NextGen NYCHA, about 8,000 residents have been placed in jobs and 18,000 have been connected with services. NYCHA launched 14 new Youth Leadership Councils to give young people the tools they need to work with NYCHA leadership to help make policy decisions that impact the quality of life of NYCHA residents, and empower them to bring their perspective to the table.

We have also seen repair response times reduced from an average of 13 days down to four days and new “FlexOps” schedules that make frontline staff available for longer service hours. NYCHA has achieved more than $313 million in savings from NextGen initiatives and NYCHA has built up nearly 3 months of operating reserves. We are proud to have served on NYCHA’s Faith Leaders Committee and are grateful for Chair Olatoye’s leadership over the last four years.

To be clear, NYCHA’s problems didn’t come with the Chair and they certainly aren’t leaving with her. It is also now up to all of us to continue to fight for the 400,000 New Yorkers who call NYCHA home. We all bear some of the burden to fix this.

We are heartened to hear the commitment of Mayor de Blasio to the NextGeneration NYCHA plan, and hope the new Chair will continue to build upon this progress. We look forward to continuing to serve on NYCHA’s Faith Leaders Committee, supporting the incoming leadership, and working together for a brighter future.

***

Rev. Marc Rivera leads Primitive Christian Church and Rev. Al Cockfield leads God’s Battalion of Prayer Church.

***

Have an op-ed idea or submission for Gotham Gazette? Email This email address is being protected from spambots. You need JavaScript enabled to view it.

The Justice System Case for Radical Incrementalism

(photo: Ed Reed/Mayoral Photography Office)

Social media was full of despair as advocates bemoaned the failure of New York state government to approve bail reform legislation in the recently-passed budget. The push to eliminate cash bail brought together dozens of organizations and hundreds of concerned citizens to advance an important reform. This kind of mobilization is not atypical – advocacy campaigns tend to focus on passing legislation or electing officials.

Eliminating cash bail is a good idea, and over time, our bet is that it will end up succeeding in Albany. But we know from the Independent Commission on New York City Criminal Justice and Incarceration Reform chaired by former Chief Judge Jonathan Lippman that you don’t need to pass new legislation in order to transform the justice system. Indeed, the commission made the case that it is possible to reimagine criminal justice in New York City – including closing Rikers Island – without any new legislation whatsoever. In fact, this process is already underway.

The Mayor’s Office of Criminal Justice has just announced that the city's jail population is now less than 8,500 – down from a high of over 20,000 in the 1990s. This did not happen overnight. It also did not happen thanks to the passage of any single piece of legislation or the election of any single official.

Reducing incarceration in New York City took place over the course of multiple decades and mayoral administrations. It was a slow, incremental process, involving dozens, if not hundreds of decisions by different agencies and actors, the vast majority of which never made newspaper headlines. For example, in 1997, New York City’s criminal court judges released roughly 50 percent of defendants on their own recognizance pending trial, without setting bail. Today, this figure is closer to 70 percent. The implications of this shift in practice are enormous – it adds up to tens of thousands of defendants being given the chance to avoid the harms and abuses of Rikers Island.

Based on our work in New York and our recent examination of successful reform efforts across the country in Start Here, we argue for an approach to criminal justice reform that focuses on practice not politics. We believe that we need to transform the culture of our justice system – and that the best way to achieve this is by working directly with the police officers, prosecutors, judges, and correctional officials who staff our precincts, jails, and courts to help them change the way they do their jobs on a daily basis.

Many criminal justice reformers go over the heads of practitioners and speak directly to elected officials. Legislating change is an enormously tempting path to pursue. A successful bill in Albany or Washington can alter the course of government more or less overnight. At least that's the promise. In reality, things often don't pan out that way.

As Michael Lipsky pointed out more than a generation ago in Street-Level Bureaucracy, frontline staffers can sabotage or undermine any initiative that they do not believe in. That's why real criminal justice reform requires time – time to change the hearts and minds of the people who run the criminal justice system.

Let’s be real: it can be profoundly frustrating to take an incrementalist approach to reform. While there is much to celebrate in New York City, which now has the lowest rate of incarceration of any major American city to go along with dramatically reduced levels of crime, there is also much work still to be done. A trip to criminal court reveals that racial disparities are still very much with us. A visit to Rikers Island indicates that we have a long way to go before we can say that our system treats defendants with decency and dignity.

Here are three changes in practice that would go a long way toward making our justice system more fair and more effective.

First, police officers and prosecutors need to create off-ramps so that more low-level cases can be diverted out of the system entirely. Second, judges and court administrators need to do everything in their power to expedite case processing and avoid unnecessary delays – especially when defendants are being held in jail pretrial. And finally, elected officials need to make deeper investments in pretrial services and alternative sentencing programs so that judges have options beyond jail and nothing.

None of these fixes requires new laws to be passed -- just the active engagement of the people who run the justice system in New York City. The good news is that policymakers are aggressively pursuing all of the above.

New York City is a case study for the kind of justice reform that takes a long time to see to fruition – but it’s the kind of reform that is both durable and sustainable. The process is gradual; the results are nothing short of radical.

***

Greg Berman is the director of the Center for Court Innovation and co-author of Start Here: A Road Map to Reducing Incarceration (The New Press). Julian Adler is the director of policy and research at the Center for Court Innovation and co-author of Start Here.

***

Have an op-ed idea or submission for Gotham Gazette? Email This email address is being protected from spambots. You need JavaScript enabled to view it.

A Closer Look at This Year’s Specialized High School Admissions

(Edwin J. Torres/Mayoral Photography Office)

Critics of the test used for admitting students to New York City’s specialized high schools -- Brooklyn Tech, Stuyvesant, Bronx Science, and five others -- failed to properly assess this year’s test and admission results because they yearned for a more robust increase in offers to black and Latino students, when compared to the year before. The city had improved the test and increased outreach and free test prep, all efforts intended to redress their underrepresentation, but in a school system where more than 70 percent of students are from black and Latino families, just 10 percent of the seats in the specialized high schools were offered to students from those communities.

This disparity is unacceptable. But so too is a failure to properly analyze the test and admission results, and thereby call the city’s efforts a total failure and demand simply that the test be eliminated in one way or the other. Such an approach overlooks what is and can be done to help remedy the city’s decades of neglect in many of the schools serving black and Latino communities.

While a sudden turnaround was not to be expected, this year’s test results did show that as a percentage of all offers, there was a small increase in offers made to black students. In absolute terms, 207 black students received offers compared to 194 the year before. On the other hand, Latino admissions declined by 10, to 320 from the latest test. Because both white and Asian offers of enrollment declined this year, both absolutely and as a percentage of total offers made, it could be argued that these results potentially show an inflection point for black admissions. However, since the students self-identifying as “multi-racial” nearly doubled, to 128, and because the race of 419 others is unknown, it would be premature to make such a claim.

Also ignored by critics of the test, was any appreciation of the city’s contradictory efforts.

On the one hand, it increased free test prep. On the other, it changed the test, making it harder to prepare. While the Brooklyn Tech Alumni Foundation, which I head, supported changing the test to make it better aligned with what is supposed to be taught in our schools, and thereby mitigate against a test prep advantage, we shouldn’t entirely ignore this issue in our discussion of the latest test’s results.

Notably, while 450 more Asian students took the test this year, fewer were admitted this year than last in both absolute and percentage terms. Because the accusation has frequently been made that the test’s results are skewed because so many Asian students do test prep, the city’s effort to mitigate test prep advantages may well have worked. Since the city is again changing the test to be administered later this year, by, for example, including poetry, a fair and proper assessment of the city’s efforts may take a few more years.

Other efforts can and should be made. One step the city could take is to revamp the Discovery Program – a long-standing, if unused, program which lets “disadvantaged” students who fall just short of the test’s cut-off score get a second chance for admission. By a targeted redefinition of what “disadvantaged” means, focusing on the underrepresented schools and communities, more high-performing black and Latino students will have increased chances for success.

Another effort that should be adopted is the bill in Albany sponsored by Bronx State Senator Jamaal Bailey, a Bronx Science graduate, that mandates administration of a free and voluntary practice SHSAT, the specialized high school test, to be offered in sixth grade, with students receiving an analysis of test results to identify areas in need of improvement before the test is given in eighth grade. We give a PSAT for obvious reasons, why not a PSHSAT?

Alumni from all eight test-in schools believe deeply in increasing diversity at their schools, but believe just as deeply in keeping the test as the single criterion for admissions as an objective measure immune to the kinds of influence many more affluent white families use to gain entry for their children to better schools that use the kind of subjective criteria that Mayor de Blasio and others have said should replace the test. For example, the student body of Brooklyn Tech, which sits in the middle of Brownstone Brooklyn, is 80 percent students of color.

The decades of declining enrollment in specialized high schools experienced by the black and Latino communities correlates with the elimination of enriched educational programs at many of the elementary and middle schools in these communities. Today only 15 middle schools account for over half of the students in the specialized high schools; none are in black or Latino communities. A fair assessment of the city’s efforts simply cannot ignore the impact of decades of neglect by the Board of Education and its successor, the Department of Education.

Ultimately, the city needs a plan to promote the creation of pipeline middle schools located within the black and Latino communities of our city. This requires the creation of vibrant gifted and talented programs in the elementary schools and enriched coursework in the middle schools. The new chancellor would be well-advised to create such a plan.

At the same time, efforts to increase outreach, free test prep, reconfiguring the Discovery Program to enroll more disadvantaged students from black and Latino communities, among other measures, can help to promote more diversity at Brooklyn Tech and the other test-in high schools. Such efforts should be fairly and accurately evaluated, not skipped over in a rush to demand elimination of the test.

***

Larry Cary is a Manhattan lawyer and president of the Brooklyn Tech Alumni Foundation.

***

Have an op-ed idea or submission for Gotham Gazette? Email This email address is being protected from spambots. You need JavaScript enabled to view it.

The Great Select Bus Service Conspiracy: Part II

(photo: Edwin J. Torres/Mayor's Office)

This is part two of a three-part series

Denigration of Local Bus Service

In many cases, the introduction of SBS has resulted in a denigration of local bus service -- though this does not apply to Manhattan crosstown routes. Most notably this has occurred on the M15 First and Second Avenue routes in Manhattan and on the B44 and B46 routes in Brooklyn. Many riders who prefer the local are now forced to walk further to an SBS stop after waiting a half-hour for a local and seeing three SBS buses bypass their stop.

After implementation of the B44 SBS, complaints of long waits up to 45-minutes for the local forced the MTA to add additional local service, after three months and a new SBS stop at Avenue L. Although the B44 SBS uses the longer buses with a 50 percent greater capacity while the local uses standard length buses, local buses are more crowded since ridership is equally split between SBS and local. Riders complain of near empty SBS buses passing them by.

Problems with Enforcement

Passengers and cars are sometimes summonsed unfairly and a kangaroo court system exists where innocent people often are found guilty. Just a few examples: convicted for theft of services, a fine of $150, when it is proven at the hearing that there was a valid transfer on the MetroCard; cameras ticketing cars for crossing the bus lane when pulling out of or entering legal parking spaces; being summonsed during hours that a bus lane is not in effect, or a minute after it goes into effect or one minute before it is no longer in effect. Should someone be penalized with a fine exceeding $100 because his watch is a minute early or late? There should be a grace period of five minutes, as with muni-parking meters. And summonses mailed three months later make it difficult to mount a court defense.

There was at least one instance in 2014, captured on video, of police shoving, harassing and kicking a passenger for five minutes after getting off the bus, although he produces ID and an SBS receipt as requested. We do not know what interactions preceded the video but it appears from the video that the individual is doing nothing wrong.

There have been instances where bus operators have told passengers to board the bus because all fare machines at a bus stop were broken and to get off at the next stop to obtain a receipt. However, before they could comply, the Eagle Team boarded the bus and summonsed them. This would not leave a favorable opinion about New York City if it happened to a tourist. The MTA has since clarified its fare payment policy when all machines at a bus stop are inoperable.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Other SBS Problems

Fare machines on the first route (Bx12) had to be replaced after three years because no one thought of providing weather protection, wasting millions. There are many SBS problems that the city and MTA have not resolved. These are: worn out pavement markings; poor and confusing signage for motorists; broken countdown time clocks and fare machines sometimes not repaired for months; inadequate exclusive bus lane enforcement; and riders who need an additional bus transfer due to SBS and are therefore required to pay extra fares to utilize SBS. (The governor recently vetoed legislation permitting an extra bus transfer for a single fare.)

The picture of the Nostrand Avenue bus lane in Sheepshead Bay was taken a year after implementation in 2014. It still has not been repainted.

Drivers are supposed to know that right turns must be made from the bus lane even on blocks where a “Buses Only” sign is posted on the prior block, although there is no additional signage to indicate that. Actually, right turns must be made from the bus lane about 50 feet after the “Buses Only” sign (pictured). Where signs do indicate right turns

are allowed (pictured) the words “& Right Turns” are too small to be easily read at speeds over 20 MPH. They should be the same size as the words “Buses Only.”

Machines are not always placed where they are easily seen, making them easy to miss if you are running for a bus and are not aware beforehand that the route is SBS. Occasionally, non-SBS wrapped buses are used in SBS service which accept fares subjecting you to a summons if you board not realizing you are on an SBS bus. The signage at bus stops also could be clearer. The print stating "Get Ticket Here" and in much smaller print "Before You Board Bus" could be interpreted as paying before you board is an option. “Get Ticket Here” should be preceded with "YOU MUST" in large capital letters. To make matters worse, bus operators may not inform confused passengers who they see boarding without a receipt that one is necessary.

The 60-foot buses used on many SBS routes are more difficult to maneuver, do not work well in snow storms, have higher labor and fuel costs, and are more inefficient than 40-footers when the bus is lightly loaded. Yet the MTA does not substitute them with regular-length buses during times of light usage, such as during evening and overnight hours.

All SBS problems need to be addressed before the system is expanded further.

Negative Effects on Traffic and Local Businesses

There have also been negative effects on traffic caused by exclusive bus lanes that are being ignored or explained away. The Woodhaven Boulevard SBS has helped increase automobile travel times during peak hours by as much as 45 minutes. This is significant because about 80 percent of motor vehicle traffic is not bus riders and SBS is not attractive enough for people to switch to the bus. Bus lanes on Woodhaven Boulevard do not result in faster buses in the off-peak, but are mostly in effect 24/7 anyway. Curbside bus lanes on Saturdays were not necessary and have hurt businesses. The longer bus stops required for 60-foot buses reduce available parking.

DOT is proposing exclusive bus lanes on the wide portion of Kings Highway for the B82 where buses are already traveling near the 25 MPH speed limit except for three hours a day. This will also negatively affect traffic and will not benefit bus passengers. Merchants and elected officials are opposing bus lanes on the narrow portion of the road.

Public Participation is Inadequate

The “democratic process” used to create SBS routes is an illusion. There is no specific outreach to alert motorists; public meetings are not adequately publicized, and there have been complaints of some of them being held at inconvenient hours; SBS information for proposed routes and SBS progress reports are difficult to find on the internet; no public hearings (different from meetings) are held; many community concerns and negatives, such as reduced parking, are ignored; half-truths are presented with many omissions; DOT and the MTA only respond to questions they want to answer.

Community groups are allowed only one representative at Community Advisory Committee meetings. However, DOT stacked at least one of the 2015 Woodhaven Boulevard meetings with three supporters from Transportation Alternatives.

When actual traffic data was questioned, it was substituted with modeling data not presented at that meeting. The presentation was then revised and backdated to make it appear the modeling data was presented at the meeting rather than the actual traffic data. Modeling assumptions were not revealed.

After initially stating to the communities that there was no relation between SBS and Vision Zero, DOT made SBS and Vision Zero part of the Complete Streets Program in order to use funding earmarked for Vision Zero to expand SBS. Underhanded tactics such as these have been a hallmark of the SBS program.

The process is dragged out to give the illusion of democracy when many meetings are not even necessary. Combined meetings could be held with more than one merchants’ association at a time in a given corridor cutting years off the SBS implementation process.

Instead, the divide and conquer strategy is used to prevent many negative opinions at the same time. It also affords the agencies the opportunity to provide different and conflicting responses to each group. The same strategy was used at the presentations to the general public. Plans are presented in bits and pieces so that communities do not see the complete plan. The promises and positives of SBS were presented as a sales pitch. The public was then divided into workshops of six people each with the discussions led by DOT employees, ensuring that everyone heard all the positives but not the negatives in coherent form. That resulted in no negative being heard by more than five other individuals instead of 30.

At the initial meetings, at least along Woodhaven Boulevard, problems and suggestions from communities were discussed with SBS presented as one possible solution. At subsequent meetings SBS was proposed as the only solution for all bus problems and community support was requested. At one Woodhaven Residents Block Association meeting where DOT was summoned to attend, an informal vote of SBS support was taken in which 100 opposed the SBS plan and only one was in favor. DOT’s response was that SBS would still be implemented. Since SBS was now a given, curbside bus lanes were proposed by the community, but DOT chose center roadway lanes instead, over community fears of decreased safety.

Any suggestion other than SBS is summarily dismissed. Only massive and organized protests can alter the pre-existing SBS solution. It took a major effort to reverse most of DOT’s 26 additional proposed left turn restrictions on Woodhaven Boulevard; DOT admitted to only 19 on the last page of their FAQ document, implementing a northbound restriction at Rockaway Blvd, while proposing a southbound restriction. Still, there are no signs to alert drivers where the next left turn is allowed, while they are only about once a mile, despite DOT promises of advance signage. That causes unfamiliar drivers to go far out of their way since right turns are also not allowed from the center roadway except for a few slip lanes.

Just recently, DOT agreed to eliminate Saturday bus lanes on Cross Bay Boulevard. Repeated suggestions for a B44 SBS stop at Avenue R were ignored prior to implementation. Residents and elected officials have now been fighting for five years for this needed bus stop.

Community involvement is far from adequate.

This is part two of a three-part series. Read part one here. The final part discusses why SBS is not a cure all, if it can work, and whether it is worth it.

***

Allan Rosen is a former director of Bus Planning for MTA New York City Transit. On Twitter @BrooklynBus.

***

Have an op-ed idea or submission for Gotham Gazette? Email This email address is being protected from spambots. You need JavaScript enabled to view it.

Assignment for the New Schools Chancellor: Address Race Head-On

(Credit: Photographer/Mayoral Photography Office)

When I was in 5th grade at a public elementary school in Manhattan, my teacher was Mrs. Camiji, and I loved her. She taught us about diverse cultures all over the world, and pushed us to think about what roles we could serve in our community. It was empowering to see her in front of the classroom. She was the first African-American classroom teacher I ever had, and the last African-American classroom teacher I had until college.

Ms. Camiji was part of the reason I have been so committed to education as an adult. Over the past four years, I dedicated hundreds of hours serving on the city’s Panel for Educational Policy and voting on hundreds of policies affecting the students of color who make up the vast majority of the city’s public school students. But extremely few of those policies have directly addressed the racism and bias in our schools that are obstacles to academic achievement.

In his State of the City speech a few months ago, Mayor de Blasio said, “We face an achievement gap today that is rooted in the enslavement of Americans and the pervasive discrimination against people of color over centuries. We know exactly where the problem comes from, but to defeat structural racism and to overcome this achievement gap, we have to flip the script. We have to do something different when it comes to education….”

The mayor is right, and he is in a position to change this. Former schools Chancellor Carmen Farina made many positive changes in New York City public schools - elevating the role of educators, diminishing the role of standardized tests, expanding community schools, and other great initiatives. But over the past four years, this administration has danced around issues of systemic racism in schools, unwilling to confront it directly.

Despite a deep body of research showing that students are more likely to succeed academically when they see themselves reflected in the books and curriculum they read, in the courses they take, in the issues discussed in class, I have seen very few system-wide policies that reflect this approach to advancing the success of students of color, beyond small and excellent initiatives like NYCMenTeach and Expanded Success Initiative.

I hope that the new leader of the school system, Chancellor Richard Carranza, will take up this issue and do more than the administration has so far.

Chancellor Carranza has seen first-hand, as a principal and a superintendent, the incredible impact on students of color when they learn about their own history and culture, and from educators who understand and connect with their history and culture. He has a reputation for engaging families in genuine and culturally appropriate ways, and knows the investment in schools that approach builds.

My daughter graduated from high school last year, and she never had an African-American classroom teacher in New York City public schools. In elementary school there was one African-American music teacher; in high school there was an African-American substitute science teacher. The students loved that science teacher, and my daughter confided in him and relied on his input to shape her decisions and keep her focused. But it’s a disgrace that my daughter’s teachers were no more diverse than my own, 25 years earlier.

Mayor de Blasio and Chancellor Carranza, let’s make this the last generation of New York City public school students who have to experience what my daughter and I have. Let’s grow the number of teachers and administrators of color, increase cultural competency among all teachers, and diversify curriculum and course offerings. This is the path to expanding academic success among our students of color, and for all students.

***

Elzora Cleveland is a former mayoral appointee on the Panel for Educational Policy, and a parent leader with the NYC Coalition for Educational Justice. On Twitter @CEJNYC.

***

Have an op-ed idea or submission for Gotham Gazette? Email This email address is being protected from spambots. You need JavaScript enabled to view it.

Promoting Tenant Advisory Groups in Supportive Housing

(photo via nycha/flickr)

The supportive housing model recognizes the inherent dignity in all people. Low-income tenants and people with mental health conditions who were formerly homeless are offered an affordable apartment combined with voluntary supports and services that can help increase self-determination. As supportive housing grows in New York and the country, tenant engagement and empowerment are recognized as important factors in maintaining secure and thriving residences.

Tenant advisory groups are a promising initiative taking hold in New York supportive housing, and may be a scalable approach to encouraging self-advocacy and recovery. In advisory groups, tenants exchange experiences, propose solutions and initiatives, and provide feedback to management regarding issues at their residences. This setting encourages tenants to advocate for their needs and collaborate on meaningful decisions about their home life and community.

Creating an advisory relationship between tenants and staff also builds trust and mutuality, which can be an important foundation for people as they recover from disempowerment experienced while homeless. In addition, it strengthens tenants’ communication and leadership skills as well as their relationships with neighbors and community members.

A tenant advisory group doesn’t only helps supportive housing tenants; the approach also enhances the residence itself. In particular, the process helps ensure issues at the residence are addressed by staff and senior leadership in a way that respects tenant priorities and preferences. Advisory group members become trusted peers in each residence, and can represent the needs of neighbors who don’t feel motivated to self-advocate. Elected tenant leaders also provide a valuable and personal perspective to staff that they may not access otherwise.

Community Access, a 44-year old nonprofit that empowers mental health recipients by providing quality housing and employment services, created a tenant advisory council, known as the Program Participant Advisory Group (PPAG), over four years ago. One of the first in New York City, the PPAG is a tenant body democratically elected by Community Access tenants that advises senior management and creates initiatives. For example, the PPAG designed a program that offers small grants to tenant applicants trying to regain employment. Grants have enabled tenants to complete courses in massage therapy and medical billing and obtain licenses and certificates in commercial driving and food handling. The PPAG also initiated karaoke events.

Each month, the PPAG brings its own karaoke equipment to a different Community Access residence and facilitates an event where tenants and staff share songs and build community as well as share events and community resources. Tenants travel from all over the city, getting to know new neighborhoods and meeting other tenants. Karaoke events are one of the most well-attended Community Access events, in part because they were started and are run by tenants.

Urban Pathways - a 43-year old social services and supportive housing nonprofit for homeless adults - also engages in robust advisory group efforts. Each transitional and permanent housing residence holds a regularly occurring self-advocacy group where individuals address residence issues and work on self-advocacy. Urban Pathways also holds a twice monthly Thursday night issue-based advocacy group for current and former clients to become better issue-based advocates. Recent speakers include the Deputy Chief of Staff to City Council Speaker Corey Johnson as well as the Chief of Staff and Deputy Chief of Staff to State Assembly Member Andrew Hevesi on the role of the city and state governments in advocacy.

In this framework of engaging and empowering supportive housing tenants, on Tuesday, April 17, from 3 to 5 p.m. there will be a Forum on Tenant Advisory Groups at Fountain House at 425 West 47th Street in Manhattan.

The forum - the first in a series - will focus on starting a group and empowering tenant advocacy. Supportive housing providers currently doing advisory groups - Community Access, Urban Pathways and Breaking Ground - will discuss barriers to creating groups, provide examples of best practices, and suggest resources for providers interested in establishing groups. There will also be an audience question-and-answer session focused on four areas: how advisory groups advocate for fellow tenants; getting staff on board; involving senior management; and future goals.

We encourage supportive housing tenants, staff, and management as well as recipients of mental health services to attend the Tuesday forum to learn about how advisory groups can build upon the strong legacy of supportive housing in New York and beyond.

***

Nicole Bramstedt is the Director of Policy at Urban Pathways, a nonprofit social services and supportive housing organization serving homeless adults. On Twitter at @UrbanPathwaysNY.

Carla Rabinowitz is the Advocacy Coordinator at Community Access, a 44-year old nonprofit that empowers mental health recipients by providing quality supportive housing and employment training. On Twitter at @ca_nyc.

***

Have an op-ed idea or submission for Gotham Gazette? Email This email address is being protected from spambots. You need JavaScript enabled to view it.

Andrew Cuomo’s Missing Endorsements

Gov. Cuomo (photo: Governor's Office)

On March 19, New York’s gubernatorial race intensified when actor and activist Cynthia Nixon declared her candidacy. The incumbent, Governor Andrew Cuomo, shifted into high gear, chasing down endorsements from all quarters. He got a few -- a Senator, some labor unions, an old rock star who doesn’t live in New York. All fine and good, but where are the endorsements from the New York City Council, the Public Advocate, City Comptroller and borough presidents? Even more curious, where are the endorsements from the 133 people who know him best?

Who are these 133 people? They are the Democratic members of the New York State Assembly and Senate. They are the elected representatives who ostensibly share an agenda with the governor and, in theory, work with him to pass laws. But all 133 Democratic members of the Senate and Assembly have remained conspicuously silent when it comes to the leader of their party. What’s more, they haven’t criticized Nixon’s primary challenge. Instead, they remain in patient equipoise at a time that Cuomo seems increasingly anxious to secure support against a formidable primary opponent. Why?

The Legislature is tired of Cuomo’s business as usual. First, lawmakers are no doubt angered by Cuomo’s repeated exclusion of the chosen leader of the Senate Democrats, Senator Andrea Stewart-Cousins, from budget negotiations and policy pushes. Never has this been more glaring than this year, when he publicly promised to seek her feedback on sexual harassment laws, and then reneged -- but kept Senator Jeffrey Klein in these negotiations despite the accusations of sexual assault recently leveled against him. In a year where the #MeToo movement has flexed its considerable political power, Cuomo underestimated the impact of excluding women from negotiations (resulting in a sexual harassment package, and budget, that is not even close to as strong as it could have been).

Second, Cuomo has mismanaged his preferred mechanism for excluding Senator Stewart-Cousins from the leadership, otherwise known the Independent Democratic Conference (IDC). Albany’s worst-kept secret is that this rogue group of senators, Democrats who have empowered Senate Republicans to run the State Senate since 2011, has been supported by Cuomo. Seven years ago, Cuomo could get away with this. Now, in the age of Trump, enabling Republicans is untenable.

It took Cuomo too long to realize his support of the IDC hurts him at the polls, as it has with fellow Democratic elected officials. In fact, in a miscalculation of epic proportions, he kept the IDC on during budget negotiations. He could have had a trifecta of Democrats (himself, Carl Heastie and Sen. Stewart-Cousins) build the budget, achieved if he had called special elections earlier in the year. Instead, he waited, calling them for April 24 so he could keep Sens. Jeff Klein and John Flanagan in budget negotiations with him instead. As a result, the budget left out major planks of the Democrats’ progressive platform, like early voting, the Child Victims Act, criminal justice reforms, and more. New Yorkers noticed. In particular, many Westchester voters (those suburban voters that Cuomo so eagerly courts) noticed because they went unrepresented in budget negotiations, and their empty Senate seat could have tipped the balance of the upper chamber to the Democrats.

This budget fiasco caused Cuomo to scramble to solve his IDC problem. His promised “deal” to reunify the IDC with the mainline Democrats, originally scheduled for after the special elections, abruptly accelerated. In a hastily devised agreement, Cuomo forced Sens. Stewart-Cousins and Klein to shake hands for the cameras and work out most of the details later, without even the courtesy of a heads-up to Sen. Stewart-Cousins before the meeting where he exerted a unifying power he had not-that-long-ago said he did not possess.

Democratic lawmakers across New York have good reason to doubt the veracity of this rushed reunification. (Progressives are also dubious.) Perhaps they recall 2014, when Cuomo, in order to secure the endorsement of the Working Families Party, promised to undo the IDC (that never happened). They see that the IDC continues to hold high-dollar fundraisers, with Cuomo in attendance, signalling that real unification has not happened at all, and the IDC’s return to the GOP is inevitable. Perhaps they are just tired of Democrats who need to be forced to work with their own party, who hold bills hostage in committee, and suck up an unfair share of legislative resources year after year. Whatever the reason, Cuomo’s after-the-fact “reunification” of the IDC with the mainline Democrats is truly a case of too little, too late.

The governor wants to get these missing 133 endorsements, by hook or by crook. During the press conference announcing the “reunification” deal, Cuomo declared by fiat that the newly united Democrats will support one another, including his gubernatorial campaign. Yet, the 133 endorsements have still failed to materialize. Democratic lawmakers are resisting Cuomo’s machinations in the one way they can, and as they say, the silence is deafening.

***

Lisa DellAquila is a co-leader of True Blue NY. Heather Stewart is an organizer with Empire State Indivisible. On Twitter @makeNYTrueBlue and @es_indivisible.

***

Have an op-ed idea or submission for Gotham Gazette? Email This email address is being protected from spambots. You need JavaScript enabled to view it.