After 28 Years in Office, Jeff Aubry Faces Tough Assembly Primary from Disgraced Former Senator Hiram Monserrate

Assemblymember Jeff Aubry (photo: State Assembly )

This story was first published by the Queens Daily Eagle

Eleven years have passed since Queens Assemblymember Jeff Aubry led the successful effort to repeal the state’s Rockefeller drug laws and address the brutal impact of the War on Drugs on communities of color. Since that fight, Aubry has sponsored legislation to ensure inmates have access to mental health treatment behind bars, introduced a bill to curtail the use of solitary confinement, and called for a special prosecutor to investigate prison deaths and complaints made against correction officers.

The 14-term incumbent, who once taught at a New Mexico prison in the early 1970s, championed criminal justice reform long before criminal justice reform became a hot issue among his Democratic colleagues.

“I’m proud of the way young people in the Senate and Assembly have come to this battle,” Aubry told the Eagle June 10, a day after he voted to eliminate 50-a, the state law that shielded police personnel records. “Once we’re on a roll with justice, you try to keep that ball rolling.” But the ball may keep rolling while he watches from the sidelines.

Aubry, 72, is facing the toughest primary challenge of his 28-year career. Perhaps fittingly, it’s the tenets of criminal justice reform — second chances for the formerly incarcerated, a complex life beyond the superficial label of ‘convicted felon’ — that inform the viability of his opponent, Hiram Monserrate. Or at very least, it’s what enables some supporters to justify their votes for an extremely polarizing politician convicted of cutting his girlfriend and stealing public funds.

In November 2019, Monserrate, a former state senator and City Council member, declared that he would challenge Aubry in Assembly District 35, which covers much of Elmhurst, East Elmhurst, Corona, and LeFrak City. To many voters, the name “Hiram Monserrate” is synonymous with a recent era of political corruption that saw numerous state elected officials charged, convicted and sentenced for bribery, kickbacks and steering schemes.

Monserrate, who did not respond to multiple phone calls, emails, and Twitter messages for this story was sentenced to two years in federal prison in 2012 after he funneled City Council money to a nonprofit and used the cash to boost his Senate campaign. He was ordered to pay nearly $80,000 in restitution, but by February 2020, he had paid less than $9,000.

He told the New York Times he would pay the rest leading up to the primary. It remains unclear whether he actually has paid the money back. The U.S. Attorney’s Office in Manhattan, to whom he owes the money, did not immediately respond to emails and phone calls.

Monserrate was also convicted of a separate domestic violence-related misdemeanor in 2009 after he cut his then-girlfriend in the face with a glass, dragged her to a car, and drove her to a far-away hospital. He and his then-girlfriend said the gash she suffered was the result of an accident.

If that wasn’t enough baggage, Monserrate is known for grinding the Senate to a halt by briefly siding with Republicans and nullifying the slim and, at the time extremely rare, Democratic majority.

“The rise and fall of Hiram Monserrate is like a movie,” Aubry said. “He robbed, he stole, he beat his girlfriend and still he rises. It’s a sexy story and any darn writer can make a novel about that. And I think he sees himself that way.”

On the Ground in Elmhurst and Corona

New York City will soon find out how voters see Hiram Monserrate.

His campaign signs adorn the walls of various shops and businesses around Elmhurst and Corona, though that does not necessarily mean that passersby — or even the store owners themselves — know who he is.

At a bus stop near the corner of Grand Avenue and Queens Boulevard, not far from the Queens Place mall on June 18, five people who said they were registered to vote in the area said they had never heard of Monserrate, whose sign hung in the window of a doctor’s office behind them.

Across the street, a man named M.D. stood outside a bodega and counted himself a Monserrate supporter. “He’s a gentleman. I’ve known him for years,” M.D. said as he scratched off lottery tickets against a railing. A Monserrate sign hung from the window of an Indian restaurant next door.

“Somebody just came and pasted it on the wall,” said the restaurant owner. “I said, ‘OK.’ I don’t know him.”

The same thing happened at a discount store a few blocks away, the store clerk said.

“Some kids just came by and asked if they could put the signs up. We said, ‘Yes,’ but I don’t know who he is,” she said.

The demographics have shifted significantly in District 35, with Latino residents now accounting for more than 60 percent of the population — up from 52 percent in 2012. At the same time, the district’s Black population has decreased. The demographics could help Monserrate, a Latino candidate who connects with many voters in their native language, said political strategist Martha Ayon, who lives in District 35 and has endorsed Aubry.

“From November, all the way until February they could have been doing articles and going on TV in Spanish to criticize Hiram,” Ayon said. “They didn’t take the time before this to reach the Spanish audiences. “You need it to be in El Diario and some of the other Spanish publications in Queens.”

In recent weeks, Aubry’s campaign has circulated Spanish-language literature, but Ayon said it was already too late to reach many voters.

“They weren’t persuading them in the language that they understand,” Ayon said. “Why don’t people care about his criminal history? Because you’ve been saying it in English,” she added.

Younger voters, meanwhile, may not recall his past misdeeds — or Aubry’s achievements

“My story is longer and maybe not so flashy,” said Aubry, who is Black. “You get a younger population where Rockefeller is like the First World War.”

Monserrate has already been elected to a party post during his post-prison comeback. Assembly District 35 Democrats chose him as a district leader in 2018.

During that election, Monserrate helped carry three other other members of his East Elmhurst Corona Democratic Club to district leader victories as well. The four officials are gadflys among the borough’s 72 elected district leaders — two men and two women in every Assembly district. They refuse to support the county party’s endorsed candidates and Monserrate has been an outspoken opponent of the organization, which has long backed Aubry.

Though Monserrate did not respond for this story, loyal surrogates have repeatedly come to his defense.

“If we speak about reform and forgiveness and giving people a second chance then we speak to people who are critical of Hiram,” said Monserrate’s friend and ally Anthony Miranda, a retired police sergeant running for Queens borough president. Ten years ago, Miranda lost to Aubry in the Democratic primary for Assembly District 35. He has received campaign contributions from Monserrate during his bid for borough president.

“I don’t agree with any of the things he’s been accused of, but he was found guilty, he served his time, he came back to the community. And the community residents voted him in,” Miranda said, referring to the district leader election.

Monserrate, a gifted retail politician, has remained active in the community, developing relationships and laying the groundwork for his campaign through his political club.

“Hiram has been physically working and getting out the vote for months, doing mutual aid, handing out PPE, door-knocking and that’s not something that should be taken for granted,” Ayon said.

Monserrate has advised the anti-displacement coalitions Nos Quedamos and East Elmhurst Alliance, which advocate for affordable housing in Willets Point. After the Eagle referenced Monserrate’s criminal history in a 2018 article about those efforts, an East Elmhurst Alliance representative wrote a message explaining why the members value and support Monserrate.

“We believe in fully re-integrating our returning citizens. He has done lots of great things in our community and quite frankly our Coalition has gotten more than a full semester of Willets Point knowledge from him,” the representative wrote.

“His past errors have nothing to do with our fight at Willets Point and our Nos Quedamos Queens coalition stands by him because quite frankly he is the only Leader who is independent of the machine with the knowledge and force to stand up for us when other politicians cut deals with developers etc.,” they continued.

The East Elmhurst Corona Democratic Club has also served as a sort of power broker in the area, running a slate of candidates for elected office in the past few election cycles and hosting higher-office hopefuls like Brooklyn Borough President Eric Adams and four candidates for Queens borough president: Donovan Richards, Elizabeth Crowley, Costa Constantinides and Miranda, who the club endorsed.

Last year, the club’s pick for Civil Court judge, Lumarie Maldonado Cruz, defeated the candidate endorsed by the county organization in Queens’ first contested Democratic primary for a judgeship in decades.

The club, one of the most active in Queens, features an effective petitioning operation and has organized a get-out-the-vote initiative in the district as well. Two Corona residents said East Elmhurst Corona Democratic club members even visited their home to help their older relatives apply for absentee ballots and then returned a few weeks later with the ballots, which they had picked up from the Board of Election office in Forest Hills.

One resident, Natalia Guzman, said she answered the door and spoke with the campaign worker to prevent the woman from pressuring her mother.

“She asked if she is going to vote for Hiram Monserrate and I said, ‘She’s not going to declare that right now,’” Guzman said. “She was reluctant to let go of the ballot.”

Election attorney Sarah Steiner said that picking up blank ballots is not prohibited, but verges on illegal when a campaign worker pressures a voter while they fill out a ballot — or fills out the ballot themselves.

“There’s a fine line about what’s legal and what’s not,” Steiner said. “You can deliver absentee ballots, you can pick up absentee ballots, but if you help the voter fill out that ballot you could be breaking the law.”

Antagonists Unite for Aubry

On June 18, Aubry — far from an active social media user — tweeted a major development in the race: U.S. Rep. Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez was endorsing him for reelection. On Sunday, she even canvassed with Aubry in LeFrak City.

The endorsement was also unique in Queens politics because it united two influential antagonists — Ocasio-Cortez and U.S. Rep. Gregory Meeks, the chair of the Queens County Democratic Party, a position he won after Ocasio-Cortez defeated then party chair Joe Crowley.

“Aubry’s going to win. Here’s a man of distinction, character who has served his community with grace and decency,” Meeks told the Eagle Friday. “People in his district are recognizing that.”

Some colleagues and Queens leaders were slow to provide that sort of aggressive support for Aubry earlier in the campaign, however. While elected officials have focused on their own races and the impact of COVID-19, they have also weighed the political risks of alienating Monserrate supporters.

Aubry said he does not fault his allies for showing up late to rally behind his candidacy given the impact of COVID-19 and current political realities.

“Some folks were under pressure from outside forces in their district,” he said. “I’ve been doing this for 28 years. I watch and know politics as best as anybody else, and I know the things that people have to watch out for in their own world and have to take into consideration.”

Others spoke out early on. City Council Member Francisco Moya called Monserrate a “disgraced politician” and a “joke” when Monserrate first filed a campaign committee in November 2019. Assemblymember Catalina Cruz from the neighboring 39th Assembly District sponsored a failed bill that would prevent people convicted of public corruption from serving in the state Legislature.

In March, Assemblymember Aravella Simotas vowed to leave the Democratic conference if Monserrate were invited to join after potentially defeating Aubry.

“I will not sit in the Democratic conference if he is sitting there with me,” Simotas said during an appearance on WBAI radio’s City Watch show.

“I’m very passionate about this because I’ve spent years talking with domestic abuse survivors and survivors of sexual assault and women and men who’ve had this violence,” she added. Simotas is facing a tough primary challenge of her own from Democratic Socialist of America-backed organizer Zohran Mamdani.

Yet, it’s more than just tweets and bromides. Support for Aubry has surged in recent weeks based on financial disclosure reports.

Aubry began the year with $114,000 in his campaign account but raised just under $21,000 between Jan. 11 and May 18, according to financial disclosure reports filed with the state Board of Election.

But over the next two weeks, Aubry raised more than $40,000, including a $4,700 contribution from ex-Rep. Joe Crowley’s campaign account, according to Aubry’s 11-day pre primary report.

In contrast, Monserrate raised $68,772.02 between July 15, 2019 and Jan. 11 of this year but just over $4,800 between Jan. 11 and May 18, according to financial disclosure reports. He raised another $7,150 in late May and early June, according to his latest filing.

Ayon, the Queens political strategist, said the race remains wide open a day ahead of the primary.

“That’s why I endorsed Aubry, because I’m extremely concerned,” she said.

Whatever voters think of the candidates and their pasts, there’s a practical reason to vote for Aubry, she said.

“Anyone can be an advocate, but if I’m paying someone to go to Albany and pass legislation, that is not something Hiram will do,” Ayon said. “The governor, Carl Heastie, they won’t let his legislation get to the floor. That’s my argument for Hiram and Aubry: Who can physically do the job? Hiram cannot.”

***

by David Brand of the Queens Daily Eagle

@DavidFBrand @QueensEagle

@GothamGazette

Insurgent Campaigns Try to Replicate Major 2018 Voter Turnout Jump in Very Different Circumstances

Jamaal Bowman's congressional campaign attempts to capture some 2018 magic (photo: Bowman campaign)

This story, and the series it is a part of, has been supported by the Solutions Journalism Network, a nonprofit organization dedicated to rigorous and compelling reporting about responses to social problems.

**********

After a massive wave of voters shook New York’s 2018 primary elections and subsequent state government, this year’s primary turnout could be hobbled by the lasting impact of the COVID-19 pandemic.

Whereas the 2018 primaries for state Legislature, governor, and other state-level seats saw an immense jump in voter participation from 2014, this month’s party primaries — almost all of which are again among Democrats — for president, state Legislature, the U.S. House of Representatives, and other seats, could see a drop.

Many of the strategies employed by campaigns and activists in 2018 — explored in-depth in part one of this two-part series — have simply not been possible during the coronavirus shutdown, fundraising has become a major challenge, and many voters are less able to focus on politics given the public health and economic hardships ravaging New York City.

Across boroughs and races, Gotham Gazette spoke to a diverse array of campaigns to understand how tactics have shifted throughout the coronavirus crisis, and how they are trying to draw voters to the polls — or to the absentee ballots all eligible voters can use given gubernatorial order based on the pandemic — as millions of New Yorkers' lives are upended, advantages of most incumbents appear strengthened, and there is an immense unknown when it comes to voter participation.

Several of these races are in districts that overlap with pivotal districts from the 2018 state primary elections. While there are no statewide seats on the ballot this year as there were in 2018, the state and federal primaries (state Legislature, U.S. House, president) are combined this year while in 2018 they occurred over three different primary days.

Some of the results from 2018 may be instructive in 2020, especially when it comes to the tactics and strategies used by activists and campaigns, the coalitions that formed or grew and remain active, and where within specific districts saw the largest voter turnout jumps in the prior primaries. But at the same time, 2020 has become an election year like no other in recent memory due to the pandemic.

From Door-Knocking to Delivering Groceries

The neighborhoods within Queens’ 34th Assembly District — parts of Jackson Heights, East Elmhurst, and Woodside — were some of the hardest hit in the city by the COVID-19 pandemic. In Jackson Heights, one in every 25 people have contracted the coronavirus; in East Elmhurst, one in 23 people have contracted it; and in Woodside, one of every 39 people have had it, according to Department of Health data analyzed by The New York Times.

The devastation and dangers wrought by the virus made normal political campaigning untenable. In its place, candidates started using their campaign apparatuses as mutual aid networks to help residents in need.

“My office and campaign volunteers have shifted to providing much-needed supplies and food to my constituents,” Assemblymember Michael DenDekker told Gotham Gazette. His campaign has largely been on pause since March, and only recently began again, mostly online. “The need has been overwhelming,” he said.

DenDekker is vying to keep his seat from four challengers this competitive primary season; the first time he has had to overcome any primary competition in a 12-year legislative career.

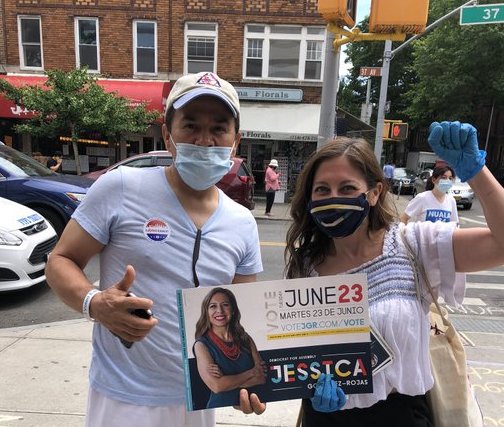

Three of his challengers — former Manhattan prosecutor and local civic leader Nuala O’Doherty-Naranjo; former National Latina Institute for Reproductive Health Executive Director Jessica González-Rojas; and Uber driver and organizer Joy Chowdhury — also began to funnel campaign energy and resources into fighting the effects of the pandemic, they said in interviews.

O’Doherty-Naranjo started the COVID Care Neighborhood Network in Jackson Heights, which delivers supplies and staffs a helpline residents with the coronavirus can use to connect to different services. Instead of fundraising for her campaign and appealing to voters, O’Doherty-Naranjo has been raising tens of thousands of dollars to support COVID Care.

“It’s a weird kind of campaign,” she said.

Chowdhury paused his campaign for a few months and started delivering food to residents in need through the Queens Mutual Aid Network. Both Chowdhury and González-Rojas used their campaign staff to deliver groceries and supplies.

“The priority was not IDing voters, but checking in on neighbors,” said González-Rojas, who has amassed significant support from progressive individuals and groups, such as the Working Families Party and immigrant rights group Make the Road Action. State Senator Jessica Ramos, who won her seat in 2018 in the partially overlapping Senate District 13 after upsetting another long-standing incumbent, former State Senator Jose Peralta, had similar progressive support from the WFP and Make the Road Action, among others.

González-Rojas and O’Doherty-Naranjo also said they have prioritized educating voters about the new, pandemic-driven practices around absentee ballots, with both campaigns noting that many voters are confused about the ballot.

Absentee ballots are perhaps the biggest wild card in this year’s primary election cycle, as the New York City Board of Elections scrambles to deliver on an unprecedented increase in absentee ballot requests. It is unclear whether everyone who wants to vote absentee will be able to have their vote counted.

Whether and how campaigns have urged their likely and potential voters to access the absentee voting process could be determinative in closer contests. While absentee voting strategies have always been important, more so in some races than others, this year’s circumstances have given such tactics an unprecedented weight.

In grassroots and insurgent campaigns, where candidates don’t have the benefit of name recognition that the incumbent has, the pandemic has made the hard task of winning even harder.

“The number one most effective thing is for the candidates themselves to be able to speak directly to voters,” said Mia Pearlman, a co-founder of the grassroots political organization True Blue NY, which has endorsed González-Rojas and a slate of other candidates in this month’s primaries. “And then after that, the next most effective thing is for activists like us to do so, or people who work with the campaign. So that’s really been a struggle for campaigns to redesign their strategy in the moment in order to reach voters.”

True Blue NY was part of a coalition of grassroots organizations that helped trigger a wave of insurgent progressive candidates to overtake incumbents in the New York State Senate in 2018. Those races, along with a competitive, intense and high-spending gubernatorial primary, and a renewed interest in local politics spurred by the 2016 presidential election, led to a record-breaking primary turnout in New York in 2018.

These factors helped Ramos, who True Blue endorsed, to victory that year. Voters in swaths of Assembly District 34, especially in Jackson Heights, turned out in force for Ramos in 2018, potentially signaling that the district could be ready for another progressive insurgent in 2020. While the races have many differences, some of the neighborhoods and players are the same.

Pearlman is concerned that challengers this year may get lost in the shuffle.

“The pandemic is an incumbent protection machine,” she said. “Everything about the pandemic favors the incumbents. And it creates a situation in which challengers are really fending off a lot of problems simultaneously.”

Campaigning Without Contact

Typical campaign tactics like door-knocking, rallies, and in-person fundraising events became an impossibility in mid-March, when social distancing measures were put in place to stop the spread of the coronavirus. Instead, campaigns amped up phone-banking and -texting operations, dipped their toes into virtual events, and tried to meet voters where they were — at home.

In Brooklyn’s competitive 9th Congressional District primary, the race to draw in voters has become more important than ever.

“We’ve had to completely shift the way campaigning works,” Krysten Copeland, the communications director for incumbent U.S. Rep. Yvette Clarke’s campaign, said in an interview.

Clarke’s campaign has conducted Zoom and Facebook Live events, and several weeks ago held a virtual campaign rally featuring various prominent endorsers to kick off the stretch run toward primary day, June 23.

The primary race looks tight: four challengers have been campaigning against Clarke, including Adem Bunkeddeko, who narrowly lost to Clarke in 2018 in what was a one-on-one contest. Other challengers this year include City Council Member Chaim Deutsch, small business owner Lutchi Gayot, and U.S. Army veteran Isiah James.

Clarke, who was first elected in 2006, represents a diverse swath of Central and South Brooklyn, spanning from Park Slope to Crown Heights to Brownsville and Gerritsen Beach.

In normal election cycles, campaigns often highlight prominent endorsements to build momentum and gain goodwill with voters. In such an unusual election year, endorsements represent one of the additionally limited tools campaigns have to catch voters’ attention.

Clarke is being backed by a long list of elected officials and power players, including U.S. Rep. Hakeem Jeffries, the 32BJ SEIU union, Senator Kirsten Gillibrand, New York City Council Speaker Corey Johnson, and State Senator Zellnor Myrie, whose district overlaps with NY-9, to name just a few. “I think it sends a strong message that the people of Brooklyn know that Congresswoman Yvette Clarke has been fighting for them in Washington,” Copeland said of Clarke’s local endorsers.

The Brooklyn Young Democrats are among those endorsing Clarke. The group’s president, Christina Das, said that the pandemic has vastly impacted campaigning strategies as they work to get candidates they support elected in Brooklyn.

“It is a stark contrast comparing 2020 to 2018,” she said.

Das and many BYD members campaigned for Myrie when he was making an ultimately successful insurgent bid for incumbent Jesse Hamilton’s seat in 2018. Instead of canvassing and knocking on doors as they did in the area in 2018, the group has been phone-banking and hosting virtual events.

“It feels so much less energizing to get on the phone from your bed…than to knock on doors,” BYD Executive Vice President Julia Elmaleh-Sachs said.

With so many people out of work due to the coronavirus-forced economic downturn, it has also been difficult for campaigns to fund-raise. “I don’t think they can give their $30 to a fundraiser right now,” Elmaleh-Sachs said of many voters.

Both Das and Elmaleh-Sachs said that they think insurgent candidates will have a tougher time this election, as those candidates often rely on new and non-traditional voters heading to the polls.

Myrie was able to score a victory over Hamilton through an extensive campaign network of political groups, volunteers, and progressive activists able to turn the tide of the district and attract new voters, a feat that may be more difficult without in-person campaigning. Additionally, Myrie snagged a broad spectrum of endorsements, including from many of Brooklyn’s big-name Democrats, such as some of the borough’s Congressional delegation, Mayor Bill de Blasio, Comptroller Scott Stringer, and Council Speaker Corey Johnson, among others.

Bunkeddeko said in an interview that he has made reaching out to residents a priority during the coronavirus crisis, participating in mutual aid efforts across the district and encouraging people to sign up for absentee ballots to not put their health at risk at the polls.

“Our big push has been to push everyone to vote absentee,” he said.

In a crowded field, Bunkeddeko said that his progressive policies and his track record running for election in the district before have helped him stand out to voters when his campaign calls.

“We’ve run the race before,” he said. “We were primarying people before it became cool.”

As of late May, Bunkeddeko’s campaign had hundreds of volunteers, made over 14,000 calls, and sent over 12,000 texts to voters, according to a campaign email. Those efforts have only intensified in June.

“One thing that’s been really powerful as we make calls for Adem in his race is the fact that you’re calling and checking in on people,” said Ricky Silver, the co-lead organizer with Empire State Indivisible, a progressive political activist group formed after the 2016 presidential election and has endorsed Bunkeddeko in NY-9.

“Phone-banking for a candidate as a part of outreach for mutual aid has been, I think, a really critical development in the post-COVID world,” Silver continued. “There’s been a real positive response to those types of outreach calls, because people are looking for help.”

In a time where so many people are looking for assistance, the outreach shows voters that the campaign is looking to help those in the district, not just “transactional ways to get elected,” Silver said.

Empire State Indivisible backed Myrie in his race in the somewhat overlapping State Senate district in 2018. Bunkeddeko has received some of the same endorsements and progressive support that Myrie did in 2018, including an endorsement from The New York Times, but endorsements from many of the major elected officials that backed Myrie have eluded him.

One of the key differences between some of the most contentious 2018 primaries and the 2020 ones is the presence (in 2018) or absence (in 2020) of the State Senate Independent Democratic Conference, whose members had lost a great deal of support from other elected officials, labor unions, and other key electoral players.

While Myrie was running to unseat a Democratic state senator who had helped empower Republicans, Bunkeddeko is again running to unseat a member of the House delegation in solid standing with most of her colleagues. While Ramos ran in Queens to similarly unseat a Democratic state senator whose conference allied with Republicans, some of the Assembly primaries happening in and around her district do not have that galvanizing element for the insurgents.

As Some Things Change, Some Things Stay the Same

Though the pandemic has radically impacted how campaigns are normally run, certain objectives remain the same: attract voters and endorsements, raise funds, and run a compelling campaign.

In the race for the 16th Congressional District, which includes parts of the northern Bronx and southern Westchester, incumbent U.S. Rep Eliot Engel faces one of the most competitive matchups of his political career and this year’s primary election cycle. Engel has three challengers: middle school principal Jamaal Bowman, retired NYPD officer Sammy Ravelo, and tax attorney Chris Fink.

Bowman’s progressive campaign has made enormous waves in recent months, netting high-profile endorsements from the Working Families Party, U.S. Rep. Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez, City Comptroller Scott Stringer, Public Advocate Jumaane Williams, and Bronx State Sen. Alessandra Biaggi, among many others within and outside New York, such as U.S. Senators Elizabeth Warren and Bernie Sanders. He has reportedly raised $2 million in campaign contributions, and has benefited from a few high-profile gaffes Engel has made over the course of campaign season.

However, the incumbent has many major endorsements of his own, including Governor Andrew Cuomo and former Secretary of State and New York Senator Hillary Clinton.

Last election cycle, in 2018, Biaggi was able to unseat a powerful incumbent, former State Senator Jeff Klein, in a district that overlaps some with NY-16. Bowman hopes to have a similar upset against Engel, who has held a congressional seat since 1989.

Biaggi’s door-knocking was a key voter engagement strategy for her campaign, and her largest shares of voters were also in the neighborhoods that had some of the highest increases of voter turnout in the district, such as Riverdale. While in 2018 the candidate and volunteers were able to pitch Biaggi’s message to thousands across the district in person, Bowman has had to adjust his own strategies in the age of social distancing.

Luke Hayes, Bowman’s campaign manager, and Biaggi’s before that, said in an interview that phone-banking and Bowman personally calling voters has been a boon to the campaign. The campaign has also sent out mailers, hosted listening tours and livestreams, and connected with volunteers. Bowman has also developed a fairly large social media following, regularly posting direct-to-camera video messages that range from reflective to inspiring to singing and dancing.

“Jamaal is like, ‘Give me more voters to talk to,’” Hayes said.

As of mid-June, Bowman’s campaign had made over 850,000 calls to voters in the district, and thousands of people have signed up to volunteer with the campaign, its representatives said. In the days leading up to the primary, as coronavirus restrictions began to ease, Bowman and the campaign were out in the field more, and are conducting a bus tour around the district to encourage voters to choose the challenger.

In a sign of Bowman's momentum, Biaggi herself recently changed her endorsement from Engel to Bowman.

“Very few people have voted for elections by absentee in New York," Hayes said of the big outstanding question of how that process will unfold and which campaigns may be best able to take advantage of the shift. "So we’re all in the same boat.”

Ravelo’s campaign also has an extensive phone-banking strategy, a representative said.

“The first weeks of the pandemic, we felt destroyed. Because nobody wanted to hear about politics,” said Catherin Corrales, a volunteer coordinator for the campaign. After two weeks, the campaign adjusted, and volunteers started making calls to check in on residents and offer information during the pandemic.

“For everybody, this is a moment to learn and come up with a new plan. In the end, this wasn’t what we were expecting, but at least we were able to do something else,” Corrales said.

Similarly, Fink said via email that he has an extensive phone-banking, targeted email and social media strategy. He is working with a local production company to make videos of himself talking about the issues on camera, as a substitute to talking to voters in real life.

Though campaigns across the city have adapted to a year of new strategies, the results of hotly contested primary races is anyone’s guess.

“You have a massive number of variables interacting in a different number of ways, it’s extremely difficult to predict,” Baruch College political science professor Doug Muzzio said in an interview. Muzzio pointed to the destabilizing effect that the pandemic has had, along with the protests brought on by the police killing of George Floyd, a black Minnesotan, as factors that could drive the election in different ways.

“In New York politics, there’s always problems going to the polls,” said Pearlman, of True Blue NY. “It’s a mess on a good day.”

With all of the issues the pandemic created, turnout for 2020 is anyone’s guess, Pearlman said.

“That, in my opinion, is the number one biggest question mark right now. What will the turnout be?”

**********

This story, and the series it is a part of, has been supported by the Solutions Journalism Network, a nonprofit organization dedicated to rigorous and compelling reporting about responses to social problems.

***

by Victoria Merlino, Gotham Gazette

@GothamGazette @victoriamerlin0

A Pandemic and A Primary in the Most Impoverished Congressional District in the Country

Ritchie Torres looks at Ruben Díaz Sr. (photo: John McCarten/City Council)

This story, and the series it is a part of, has been supported by the Solutions Journalism Network, a nonprofit organization dedicated to rigorous and compelling reporting about responses to social problems.

**********

New York City has had very limited success in the voter turnout department for congressional elections in recent years. For the 2018 congressional primaries, the turnout did go up — to 11 percent, from a shockingly low 8 percent in 2016. Though the Bronx was part of a huge surge in turnout for state elections in 2018, the last primary election to take place in the borough’s heavily-Democratic 15th congressional district, in 2016, netted a voter turnout of just under 3 percent.

That’s during ordinary times in a district that encompasses south and west Bronx neighborhoods including Hunts Point, Melrose, Tremont, Fordham, and Bedford Park, which collectively make up the country’s poorest and most nonwhite district.

To add to the structural obstacles, would-be voters are now contending with the swirling maelstrom of a still-ongoing pandemic that has ravaged poorer communities in the global epicenter of New York, and its vast social and economic consequences; a mass popular uprising against police brutality that was met with a heavy-handed response from the NYPD; and confusion over whether the primary is even taking place, and if so, in what format.

The 15th congressional district has been one of the hardest hit by the novel coronavirus in what is thus far the most affected city in the country. A mix of higher prevalence of pre-existing conditions and higher concentrations of essential workers who couldn’t work from home has led to higher death rates in the Bronx and a dire socio-economic picture.

Beyond that, the district has some special political upheaval and intrigue this year: an “open” congressional seat, up for grabs for the first time in 30 years. Longtime Rep. José Serrano announced last year that he would not be seeking reelection following a diagnosis of Parkinson’s disease, setting off a scramble to succeed him.

Even by normal-year standards, it’s a crowded race with a deep bench of political figures with history in the district, many of whom have been waiting for just such an opportunity. No fewer than five of the primary contenders are current or former elected officials — City Council Members Ritchie Torres, Ydanis Rodríguez, and Rubén Díaz Sr.; Assemblymember Michael Blake (who is also a national vice chair of the Democratic National Committee); and former New York City Council Speaker Melissa Mark-Viverito.

Also in the race are Samelys López, a community organizer and former aide to Serrano who has received the endorsement of the Democratic Socialists of America and the Working Families Party, as well as progressive heavy hitters like Rep. Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez and Senator Bernie Sanders; Chivona Newsome, a former financial advisor who co-founded Black Lives Matter of Greater New York; Tomas Ramos, a program director at the Bronx River Community Center; and a handful of others from outside the established political channels.

“I watched a panel the other day, and there were about five candidates that I wasn't even aware were running that were on that panel talk,” said Ed Mundo, a city tunnels and bridges worker who said he’s lived on the same South Bronx street since he was six years old. Mundo volunteers for a few community organizations, is active in pro-bike advocacy, and is more politically engaged than most of his neighbors, yet he still feels that there is precious little information trickling out about the candidates and the election.

In the current moment of crisis, Mundo worries that “a lot of folks are not aware there is a primary. So many folks are just accustomed to the November elections, see whoever is on that ballot, then they vote.”

The race has become particularly high-profile as a result of its position at the intersection of several broader political currents and movements — longtime political establishment versus insurgent outsiders; the chance to shift the balance of power for the first time in decades; the acute power of federal policy-making during moments of crisis in particular. There’s also the Díaz Sr. factor, as a long-serving, socially-conservative Democrat with strong name recognition, a solid base of support, and a polarizing presence is within striking distance of victory. He has no dearth of critics in the district, a fact that has seemed not to phase him; in fact, he appears to thrive in controversy. His presence in the race has driven local and national attention to the primary.

For the residents of the district, it’s an opportunity to collectively exert real influence, and the race has appeared very much up in the air. Motivating even small groups to turn out can make all the difference, lifting the voices of those living in a district with such great needs.

Several campaigns told Gotham Gazette that they were focused on providing support and services to the community in lieu of pure campaigning. “What we do is we ask people how they're feeling, how they're doing. If they need anything, if they need an errand to run, if they have a need for food,” López said in late May.

“Whenever my volunteers and I are out in the field,” said Torres, “we're limiting ourselves to distributing food and PPE and doing no electioneering out in the field at the moment. The reason for which is simple: campaigning, business as usual, would come off as insensitive to the deep suffering in the South Bronx.”

Newsome said she had her volunteers teaching people how to file for unemployment, and had been riding around the Bronx in a truck with supplies including diapers and baby food. Mark-Viverito has been working with a local restaurant to provide meals to undocumented residents. Not everyone has executed this notion without controversy; Díaz Sr. has been accused of piggybacking off of food distribution events that neither his office nor campaign was involved in to raise his profile, distribute campaign materials and electioneer.

The aid strategy has also been embraced by community organizations, who are focused on simultaneously providing the type of support that their members and clients have always relied on them for, while gently prodding them to exercise their civic voice in the election.

“We started doing care packages, and in those care packages we have a bunch of those safety supplies, some tea, some canned foods, some Asian groceries and veggies. And then we've also put resources and materials in there,” said Khamarin Nhann, campaign director for Mekong NYC, which provides community organizing, cultural activities, assistance with public benefits, and other social services for the Southeast Asian community. These materials include those related to the 2020 Census, access to health care, and elections, including information about where to vote and how to vote in-person and via mail.

The question of tone is one that comes up often as a contentious, high-stakes election unfolds amid a multi-faceted humanitarian crisis. There is real and obvious devastation throughout the district. Yet the overlapping crises to some degree present the opportunity to very plainly tie the political questions at stake to Bronxites’ lived experiences. Questions related to jobs, affordable housing, food security, health care, and police relations have never been abstract in what is the poorest and most nonwhite district in the country, but the pandemic and the social unrest have brought everything into stark relief.

“There are absolutely competing needs for our folks. We've seen our members really struggle with food or worried that when the eviction moratorium ends, will they become homeless and what that looks like,” said Sandra Lobo, the executive director of the Northwest Bronx Community & Clergy Coalition (NWBCCC). “What we've tried to do is really equip our folks with an understanding, a deeper analysis that, what they do, how they vote, and how they organize, absolutely impacts what's next for all of us.”

This has involved emphasizing that none of these issues exist in isolation, and in fact they compound; any effort to tackle the current emergencies must also tackle the circumstances that let them get so bad, especially in the district. “I think communities of color, low-income communities, have always struggled with layered issues,” said Lobo. “We've seen our folks really understand and be sophisticated about, where does the power lie, both in organizing and in the electoral system?”

There are particular groups for whom federal policy-making looms particularly large; for example, healthcare workers, many of whom are represented by 1199SEIU, a union that has endorsed Blake, who has amassed a great deal of labor support in the race.

“We've had our members engaging our congressional leaders. We've done roughly 20 video conferences with our New York delegation, where we've had members…explain the realities of what's going on in the frontline,” said an 1199SEIU official who asked not to be identified. “I think that helped our members make the connection, or made it stronger, that politics is the way that we make the transition” to a system more responsive to their needs.

Nhann said that particularly in the last couple of weeks, he’d actually seen a spike in the number of community residents interrogating the decisions of their political leaders. He dismissed “this whole notion that just because folks don't speak English, they're not aware of politics or they're not aware what's going on in the news. For the most part, our folks are actually pretty savvy.”

Dariella Rodríguez of The Point CDC, a community development nonprofit, said the organization’s approach partly centered around making clear that the district was particularly hard hit not just because of decisions made during the pandemic, but decisions made before. “Although we are struggling with the impact of covid in our community, we've been burdened with issues around respiratory health and asthma, issues with water quality — we've been burdened with those issues for a very long time. We've been saying we know when something like this happens, our community is at higher risk.”

For her part, Newsome has found a natural connection between her work with Black Lives Matter and the campaign, particularly as the outrage over police brutality again takes center stage in New York and nationally. Even before current wave of protests, Newsome said she had been part of a group pressuring Governor Andrew Cuomo to acknowledge that “the NYPD was incapable and incompetent in handling the enforcement of social distancing.” The current popular movements presented an opportunity to connect police brutality directly with political participation.

No one knows how many of the roughly 337,000 eligible Democratic voters in the 15th congressional district will cast a ballot, absentee or in-person, for this month’s election. In 2016, Serrano received just over 9,000 votes in the Democratic primary, beating an opponent who received just over 1,000. A total of about 74,000 votes were cast in the district during the 2016 presidential primary. In 2018, Serrano did not have a primary, but won the general election with around 125,000 votes to his opponent’s 5,000.

One quirk of a low-turnout race is that very small differences in the number of votes cast for each candidate can determine a win and a loss. This fact has taken on an added salience for progressives in the district given the candidacy of Díaz Sr., an always controversial and regularly offensive political figure. A pentecostal minister, he is probably the most socially-conservative Democrat holding political office in the city, having staked out positions opposing abortion and marriage equality. A comment claiming that the City Council was “controlled by the homosexual community” last year got his issue committee disbanded and prompted calls for his resignation. He has also called into question the mandate to report sexual harassment.

Nonetheless, he has held political office in the Bronx for nearly 20 years continuously and enjoys a base of support with religious and conservative Latino residents, who have a strong presence in the district. He won his seat at the Council just three years ago, edging out more progressive challengers as he moved from the state Senate with at least tacit support from much of the political establishment. The concern that candidates to his left will split the vote and hand Díaz Sr. the primary win is being used to varying extents by rival campaigns.

Torres in particular appears to be making opposition to Díaz Sr. a centerpiece of the turnout effort. “From day one, I have been sounding the alarm about the threat of a Trump Republican representing the most Democratic district in America,” he said, adding that in the home stretch of the campaign, he would be pitching himself as the candidate most able to head off this threat. Díaz Sr. did not respond to messages seeking comment. He has repeatedly ducked debates in the race.

A significant concern is that there will be issues not only of enthusiasm, but mechanics. An attempt by the state Board of Elections to cancel the Democratic presidential primary over coronavirus concerns failed when a federal judge ruled that it had to be held, in response to a lawsuit filed by former presidential candidate Andrew Yang. Yet a number of voters may have heard that the primary was off, but not back on.

Disseminating the information can be difficult, partly because some of the community groups and campaigns involved aren’t entirely sure what the correct information is. “Is the election going on? Where's my polling station? Can I vote early? Who are the candidates? Where's the platform? All of those have been communicated via text via email, via phone,” said Lobo.

The point was echoed by some of the candidates. “There's a lot of confusion. There was that whole back-and-forth around the presidential primary and canceling it, not canceling it. So some people assume that the primary completely is canceled,” said Mark-Viverito.

Some number of voters won’t want to go to the polls due to the extant viral threat, leaving the option of absentee voting, and herein lies another problem: unlike 34 other states, New York typically doesn’t allow “no excuse” absentee voting. In April, Governor Andrew Cuomo issued an executive order making the coronavirus part of the existing “excuse” of illness and directing county boards of elections to mail absentee ballot applications to all eligible voters, but the lack of a prior generalized avenue for absentee voting has left many voters unfamiliar with how it works and the New York City Board of Elections appears to be straining under the demand, leaving many unanswered questions as voting of all kinds wraps up on primary day, June 23.

Mundo, the community resident, said he’d gotten a ballot application in late May. “It looks like traditional junk mail. So if you're not actively looking for it, you may bypass it. Or someone like my mother, who's been out of town since April, she's not even going to get that application.”

Rodríguez of The Point said that the group had been providing staff members specifically to explain to voters how poll sites (both for early voting and primary day) work and how to access absentee voting. “We're using apps to do mass texting, we're using social media, we're using Zoom, WhatsApp and Signal. There's even been suggestions of other kinds of apps that folks from other countries use, especially Southeast Asian communities,” she said.

The Point, NWBCCC, and Mekong all had a built-in advantage in that they were part of a coalition that spent months crafting a “people’s platform” that had community delegates participate in crafting a set of issues and proposals meant to be representative of the entire district’s political priorities. The listserv has been useful in disseminating information to the community at large, even via word-of-mouth from individual influential residents.

Fundamentally, the winning approach seems to be one of illuminating how the extant crises are manifestations of broader systemic issues. “You can’t separate the political from the personal, especially at these times,” said López. “So this is the time that we need to rally and organize for the kind of society that we want to live in. And those are the kinds of conversations that we've been having through the phone banks.”

**********

This story, and the series it is a part of, has been supported by the Solutions Journalism Network, a nonprofit organization dedicated to rigorous and compelling reporting about responses to social problems.

***

by Felipe De La Hoz, Gotham Gazette

@FelipeDLH @GothamGazette

Voter Turnout in New York City Was Cratering; Then Came 2018

Alessandra Biaggi on the 2018 campaign trail (photo: @Biaggi4NY)

This story, and the series it is a part of, has been supported by the Solutions Journalism Network, a nonprofit organization dedicated to rigorous and compelling reporting about responses to social problems.

**********

On the night of September 13, 2018, a wave crashed through New York state politics.

For years, pressure had been mounting on the members of the Independent Democratic Conference, or the IDC, a small group of high-profile and controversial Democrats who caucused with Republicans in the New York State Senate. At times, the IDC effectively barred the mainline Democratic conference from holding a majority in the chamber, hobbling party-backed legislation and affording its members major leverage in Albany.

The presence of the IDC also appeared to hamper Democratic efforts every two-year cycle to swing certain State Senate districts from Republican to Democratic hands, meaning a split Legislature with Democrats in control of the Assembly. After the election of President Donald Trump in November of 2016, significant additional pressure grew on the members of the IDC and their Democratic allies, which included Governor Andrew Cuomo.

By April of 2018 and facing his own reelection campaign with a primary challenge from his left, Cuomo brokered a deal with the IDC to dissolve and rejoin the mainstream Democrats, with an eye toward capturing the majority together as Cuomo sought to quell a progressive uprising and secure a third term. But the damage was already done, at least for IDC members who provoked such backlash in their districts that activists were set on removing them from office.

A group of largely young, progressive challengers rose up in the districts, recruited and bolstered by the Working Families Party, grassroots groups, community activists, and a smattering of elected officials. By the end of primary night in September 2018, six of the eight former IDC members had been knocked out (while Cuomo secured victory by a wide margin).

Those Senate challengers would go on to win their general elections and, along with newly elected colleagues that gave Democrats the majority, become massive forces in Albany, championing landmark rent, criminal justice, gun control, environmental, and voting reforms — among others — that were centerpieces of a historic 2019 legislative session.

Though some of the most striking images of that September 2018 primary election night come from the victors — pictures of the Bronx’s Alessandra Biaggi with her fist raised in the air, or Queens’ Jessica Ramos surrounded by cheering supporters — images only tell part of this story.

The other part isn’t as flashy, but speaks to something more powerful: voter turnout. Voters across New York went to the polls in record numbers for the 2018 state primary elections — the gubernatorial primary more than doubled the votes cast four years prior, and some districts surpassed turnout during the 2016 presidential primary. Still, New York City voter turnout numbers have a long way to go, never in recent years hitting 40 percent in a primary other than when there is a presidential election, a trend that helped lead to the sweeping electoral and voting reforms, like early voting, passed in 2019.

The map below shows where turnout increased the most and the least in the 2018 Democratic gubernatorial primary compared to the 2014 primary.

Overall, the Senate districts represented by IDC members saw voter turnout spikes in line with the overall trend, but within those districts, much of the increases came in geographic areas where the challengers did especially well, a new Gotham Gazette analysis shows.

The reasons for the voter spike are far more complex than a single night, or even the months of anger among Democrats who finally learned about their rogue state senators. And while in 2018 many New York Democrats were still reeling from Donald Trump’s election as president, it wasn’t that simple either — individual campaigns, newly-formed grassroots groups, and long-standing labor unions and other organizations all played a role in bringing many more voters to the polls. Some relied on tried and true tactics, while others got more creative.

The groups that rose or grew in 2018, and the tactics they developed that year, were ready for a big 2020 — until the pandemic hit. But many of the same activists are again doing all they can, albeit under very different circumstances, to see their favored candidates win in this month’s primaries for congressional and state legislative races. Even as New York City could see a major drop in voter participation, those 2018 successes are still reverberating throughout the state as lawmakers pass bills dealing with public health and police accountability.

‘Trump Democrats’

Donald Trump’s divisive presidential victory in 2016 sparked a wave of renewed political activism across the United States. Huge demonstrations marked the early days of Trump’s administration, such as the 2017 Women’s March or the protests over a travel ban on countries in the Middle East and Africa.

In New York, grassroots organizations began to coalesce around electing progressives to local and state political positions. Though over half of eligible voters had turned out for the November general election in 2016, the state primary turnout rate that September was abysmal: only 10 percent of voters had come out.

For many, the Independent Democratic Conference (IDC) of the State Senate was the first on their list for change.

“People were angry,” said Mia Pearlman, a co-founder of True Blue NY. The idea for True Blue was born soon after Trump’s election, at a Park Slope meeting where people were gathering to politically organize.

“A lot of people who were at the meeting lived in [State Senator] Jesse Hamilton’s district at the time and were really upset to find out the morning after Election Day that not only was Donald Trump president, but that their own Democratic state senator was empowering Republicans,” she said of Hamilton, an IDC member.

True Blue began on the idea that even though New York was seen as a Democratic bastion by others around the country, on the state government level, it struggled to pass meaningful progressive legislation. This was in part due to the IDC, and how complacent so many Democrats were about its presence and a Republican-controlled State Senate. In the months after Trump’s election, grassroots groups like True Blue and a network of Indivisible groups sprung up and tapped into the outrage people felt to get them more involved in local politics.

In part, they pointed people angry over Trump’s election to the State Senate, with its Republican control bolstered by rogue Democrats.

True Blue began to reach out to other grassroots groups in districts represented by IDC members, building a coalition of over 45 organizations. The main strategy was voter education — whether that meant protests, phone-banking, tabling at events, handing out informational palm cards, and sending handwritten postcards to voters to convince them to turn out against the IDC.

“The biggest issue with the IDC was that most people didn’t know that their own state senator was in the IDC, or they didn’t know what that was,” Pearlman said. The groups utilized one of their biggest assets — time — to educate voters in the months between early 2017 and the September 2018 primary election.

This initial campaign against the IDC began before the districts even had candidates to put up against IDC members, which was key, according to Pearlman.

“By the time we started to recruit candidates, along with No IDC New York and other groups, we sort of created an opening for them to have the opportunity to win,” she said.

“The way that the 2018 election went was that it really started 18 months prior, with the notion of, ‘We need to go out and do constituent and voter outreach and engagement on the issues,” said Ricky Silver, the co-lead organizer with Empire State Indivisible, a grassroots political activist group formed following the 2016 presidential election and part of the True Blue NY coalition.

Silver said that the races against IDC members were powered largely by enthusiastic volunteers. Empire State Indivisible was able to draw volunteers in by hosting forums across the city about particular issues, like education funding or the climate crisis, and educating residents about how the IDC slowed progress on those issues, the importance of electing “real Democrats” and of flipping control of the State Senate (the November elections, with a focus on one Republican-held Brooklyn State Senate seat and others in the city’s suburbs, were always on activists’ minds, even as they focused on the primaries first).

“People showed up because they cared about the issues, and then we were able to get them involved because they understood the pathway to a new vision was electoral. And that’s how we were able to grow the movement,” he said.

Meanwhile, a slate of statewide races was about to rocket progressive politics, the debate over what it means to be a “real Democrat” (AKA “True Blue”), and the need to control the State Senate, to the forefront of New York political consciousness.

Backed by the Working Families Party and other progressives, actor and activist Cynthia Nixon ran for governor against Cuomo. The WFP bet big on Nixon, despite upsetting some longtime political allies, and endangering its financial support from labor unions afraid of incurring Cuomo’s wrath. Nixon’s race was accompanied by competitive primary campaigns for lieutenant governor, between incumbent Kathy Hochul and challenger Jumaane Williams, then a City Council member, as well as for the “open” state attorney general seat.

The WFP credited the threat Nixon and Williams posed to Cuomo as the reason the governor brokered the deal to dissolve the IDC, following long-standing accusations that Cuomo backed and benefited from the IDC-GOP arrangement, which Nixon made central to her campaign.

The WFP also took on the IDC, launching a campaign against what they called the “Trump Democrats” in May 2017. The campaign organized thousands of voters against the IDC, giving insurgent candidates a head start before even officially entering their races. WFP ran nightly texting and phone banking activities with over 1000 shifts, and by the end of the campaign, had identified 10,000 voters who would vote against their IDC member in the Senate.

Thanks to the shock of Trump’s victory and these organizing efforts, well over a year before the September 2018 primaries, many New York Democrats were engaged in local politics for the first time.

Central Brooklyn

In Brooklyn, trouble was brewing for Jesse Hamilton, a two-term legislator who had joined the IDC shortly before the 2016 general election.

Despite the IDC’s dissolution, many prominent borough Democrats continued to denounce Hamilton’s actions as self-serving well into the primary season, though Hamilton continued to have the support of Borough President Eric Adams.

Members of the Brooklyn Congressional delegation, state legislators, and Mayor Bill de Blasio, chose to back Zellnor Myrie, a young lawyer trying to unseat Hamilton in Central Brooklyn’s 20th State Senate District.

The campaign got a boost from the WFP, which provided Myrie with media training and campaign support, and from grassroots activists and local political clubs who wanted a bluer district.

“There was a lot of energy in the air for a real Democrat, and not a law and order Trump Democrat,” according to Myrie’s senior campaign advisor André Richardson.

Myrie’s supporters took to the streets to drum up buzz for their candidate. For the Brooklyn Young Democrats, a club that endorsed Myrie that spring, that meant extensive canvassing, door-knocking, and days of action.

“We all went out there in a storm for him, not only because [he was] against the IDC, but because he was speaking to issues in the community,” BYD President Christina Das said. Das estimates that the club knocked around 2,000 doors for Myrie, and held three or four days of actions either in conjunction with other organizations, or on its own.

A native Brooklynite, Myrie had strong roots in the district, which spans through parts of Sunset Park, Park Slope, Crown Heights, Prospect Lefferts Gardens, and Brownsville. The district is diverse, but predominantly black — of the nearly 310,000 people living in District 20 in 2018, 50 percent were black, 19 percent were white, and another 19 were Hispanic, according to the U.S. Census Bureau’s American Community Survey.

One of Myrie’s main focuses in his campaign was affordable housing and tenant protections, goals that spoke to a district that is home to an overwhelming majority of renters, who faced challenges with rising costs.

“It was a great race because everyone was kind of in it together in the neighborhood,” BYD Executive Vice President Julia Elmaleh-Sachs said.

In 2014, the year Hamilton was first elected, there were roughly 129,000 active registered Democrats in the district, but only around 15,000 voted in the primary, which was quite competitive as Hamilton edged out Rubain Dorancy, who had backing from de Blasio, among others. Hamilton won with almost 10,000 of those votes. Then in 2016, Hamilton went through primary season uncontested. In the heavily-Democratic district the Democratic primary is tantamount to full electoral victory.

2018 was going to be a very different year as those frustrated by the IDC, including many educated and activated after Trump’s election, went from not fielding a primary challenger to Hamilton to immense organizing behind Myrie.

On primary day in 2018, Myrie defeated Hamilton by almost 4,000 votes. Voter enrollment and participation in the district saw significant spikes, with 44,000 of the roughly 141,000 eligible Democrats casting a ballot. The increase from 15,000 votes in Hamilton’s contested 2014 primary to the 44,000 votes in Myrie’s victory over the incumbent made for almost a 300 percent increase in raw turnout, and the district was in line with the overall turnout jump seen in the gubernatorial race from 2014 to 2018.

Part of Myrie’s success stemmed from his ability to garner support from different facets of Brooklyn’s Democrats, from longtime black voters to newcomers and progressives, Richardson said.

“I think Zellnor’s case was a very unique case because he was able to bridge that divide,” Richardson said of longtime black voters, newcomers to the district, and white progressives. Myrie’s campaign attracted hundreds of volunteers, Richardson added, attributing part of Myrie’s success to his authenticity and speaking to the needs of the district across demographic and other divides.

Myrie nabbed the greatest share of votes in Gowanus, Park Slope, Prospect Heights, Prospect Lefferts Gardens and parts of Crown Heights and Sunset Park. In several of these areas, turnout jumped enormously from. The map below, from the CUNY Mapping Service at the Center for Urban Research, CUNY Graduate Center, shows where Myrie and Hamilton each did well:

The Bronx and Westchester

When Alessandra Biaggi, a lawyer in the Cuomo administration and former staffer on Hillary Clinton’s 2016 presidential campaign, began her campaign to unseat State Senator Jeff Klein — a founder and the leader of the IDC — from Senate District 34 in the Bronx and Westchester, she understood the stakes.

“I didn’t go into it thinking to myself, ‘I’m going to absolutely win,’ Biaggi said in a recent interview. “I went in thinking to myself, ‘We probably won’t win. But what we will do is have a win in the loss.’ Because we’re going to raise awareness about an issue that is so devastating to the state. And people are finally going to be excited about their state government and want to fight for it.”

As the head of the IDC, Klein held immense power in state government, and was a major target for progressives. With millions of dollars in Klein’s war chest and his strong web of political connections made over decades, however, most pundits considered a challenge to Klein almost unwinnable.

In 2014, Klein faced a challenge from former New York Attorney General Oliver Koppell and kept his seat fairly easily, winning with over 9,000 votes compared to Koppell’s roughly 5,000. According to voter enrollment data from that November, about 101,000 active Democrats were registered to vote in the district, which encompasses parts of the Bronx and southern Westchester County, including Riverdale, Hunts Point, Throggs Neck, Pelham Parkway, City Island, and Pelham.

In 2016, Klein was unopposed in the primary.

Biaggi’s campaign was assisted by anti-IDC groups that started educating voters in the district about the IDC before Biaggi even started running, according to her 2018 campaign manager Luke Hayes.

The campaign tapped into community members in the district, generating support in key neighborhoods through word-of-mouth. Together with Biaggi and other organized forces, they started to knock on doors.

“It was a scrappy campaign. We knew we weren’t going to outraise Klein,” Hayes said of the assumed fundraising disadvantage. By the end of the race, Klein would spend more than $3 million on his campaign, an unusually high total for a state legislative race, and 10 times more than Biaggi spent.

Biaggi said that fundraising became less integral to her campaign than canvassing and meeting with voters.

“I was going to win this thing on the doors. I laced up my sneakers every single day and I was knocking on doors,” she said. She and her supporters engaged with many thousands of voters up to and including primary election day.

She also credits young, politically active students, some high school-aged, with helping to activate the community around her campaign. About 324,000 people lived in the district in 2018. Of that number, 43 percent were Hispanic, 34 percent were white, 14 percent were black and 6 percent were Asian, according to American Community Survey data.

“When you have a dynamic candidate like Alessandra, when you can engage with a candidate one-on-one, that can counteract a lot of ads,” Hayes said.

Support from groups and officials were also key.

“Endorsements are a big deal,” Biaggi said. “If you are going to be endorsed by, for example, the Working Families Party, which was my first endorsement, it gives you legitimacy.”

The powerful union 32BJ SEIU backed Biaggi in a big way, mobilizing thousands of members to conduct phone-banking and door-knocking from six weeks before the primary. The move surprised some in the state political scene, as 32BJ’s president at the time, the late Hector Figueroa, had initially helped to kick off attempted IDC reunification with Democrats in 2017. In a 2018 interview with Gotham Gazette, Figueroa said that he thought that the IDC was not sincere in its efforts to fix Democratic unity and explained the 32BJ decision to buck the deal orchestrated by Cuomo.

Silver, of Empire State Indivisible, points to the cooperation of a litany of organizations, such as the WFP, unions like 32BJ, and grassroots organizations, as one of the keys to Biaggi’s success in appealing to a diverse district.

“It was that sort of coalescing of organizations that made it powerful,” he said.

City Comptroller Scott Stringer and City Council Speaker Corey Johnson voiced their support for Biaggi in June 2018, giving the campaign more legitimacy, adding media buzz, and bringing their networks of volunteers to campaign for her. The New York Times endorsed her later that summer.

When the results rolled in that September, it was a shocking upset: Biaggi had nabbed 19,000 votes to Klein’s 16,000. There were a total of 107,000 Democrats eligible to vote in the district that November. The jump in voter turnout from Klein’s last challenge in 2014 was significant, moving from around 14,000 voters to around 35,000 voters, or increasing by 250 percent. The parts of the district where Biaggi did best also saw the biggest jumps in voter turnout from 2014 to 2018.

The precincts Klein did best in had lower jumps in voter turnout compared to Biaggi’s best precincts. In the Bronx, Biaggi had the greatest share of votes in Riverdale, Fieldston, Kingsbridge and City Island.

“For Senate District 34, the green precincts match up well with Klein's best precincts, especially around Castle Hill and the Throgs Neck area, while most of the orange precincts match up perfectly with Biaggi's best precincts, centered around Van Cortlandt Park,” said Benjamin Rosenblatt, president of Tidal Wave Strategies, who performed data analysis and mapping for Gotham Gazette for this piece. The first map below, created by Rosenblatt, shows where turnout jumped the most and least in 2018, from 2014, for Senate District 34. The second map below, from the CUNY Mapping Service, shows where Biaggi and Klein each did well.

Western Queens

In Queens, Jessica Ramos, a former mayoral aide, was challenging State Senator Jose Peralta for his seat in Senate District 13.

Peralta joined the IDC in early 2017, claiming that it was a pragmatic choice to best serve the district during the new era of Trumpian policy. At a packed town hall soon after the decision was announced, some residents protested, calling Peralta a “traitor.”

A legislator with almost two decades of experience, Peralta had no competition in the district’s Democratic primary for the entire time he held the seat, running unopposed in the primary in 2010, 2012, 2014 and 2016.

The district’s neighborhoods, including Jackson Heights, Corona, and East Elmhurst, are home to large immigrant communities. Of its population of 302,000 in 2018, over half were born outside of the United States, according to American Community Survey data. Of the district residents, 62 percent were Hispanic, 17 percent were Asian, 14 percent were white and 6 percent were black.

Trump’s rhetoric and policies against immigrants, such as the ‘public charge’ rule or travel bans to certain countries, directly impact residents in those communities, and led many to question how Peralta could align himself with the IDC, which bolstered Republican leadership of the State Senate, preventing major immigrant-friendly legislation from passing. That included the Dream Act that Peralta championed and he apparently saw as possible to get passed with added leverage as part of the IDC.

Make the Road Action, a leading immigrant rights group that is very active in the district, endorsed Ramos for the Senate seat in July 2018, and set out to have thousands of its members phone-banking, canvassing, and engaging voters for Ramos.

Progressives in the district were energized by the stunning upset political unknown Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez had in June against then-U.S. Rep. Joseph Crowley, the Queens County Democratic Party boss and one of the highest ranking Democrats in Congress. New York’s 14th Congressional District overlaps with Senate District 13. There was a renewed sense of what was possible after Ocasio-Cortez’s win as Ramos and her supporters eyed the sprint from the June congressional primaries to the September state primaries (those primaries were merged to June starting this year).

“Most of all, I think her win has created a lot of enthusiasm for the small “d” democratic process in the district and that enthusiasm is what we’re hoping to maintain our momentum,” Ramos told City & State in the summer of 2018.

Other political powerhouses and grassroots organizations coalesced around Ramos. The WFP helped her hire key staff, consulted on her campaign, and identified thousands of voters for her. Stringer backed Ramos in March. In the summer after Crowley fell, de Blasio, for whom Ramos had previously worked, and Johnson backed her, and Ramos and gubernatorial candidate Nixon cross-endorsed each other.

On primary day, Ramos defeated Peralta by over 2,000 votes, with almost 23,000 votes cast in total. In November of that year, 90,000 Democrats were eligible to vote in the district. Ramos did far better in parts of the district like Steinway, Astoria Heights, and Jackson Heights. The map below, from the CUNY Mapping Service, shows where Ramos and Peralta each did well.

Other Races in Manhattan and Brooklyn

Other districts around the city saw increased voter turnout in the same neighborhoods where insurgent candidates nabbed the largest share of votes.

In Manhattan’s Senate District 31, former City Council Member Robert Jackson emerged victorious on primary night over former IDC member and State Senator Marisol Alcantara. Jackson had run for the seat before in 2014 and 2016, losing narrowly to Alcantara in 2016 in a three-way race. Alcantara only served one term in office before Jackson overtook her in 2018.

The largest increases in voter turnout in the district from 2014 to 2018 were in the Upper West Side, Manhattanville, Washington Heights, and parts of Inwood, all where Jackson performed the best, indicating how well the insurgent’s supporters did at turning out the vote. The map below, created by Rosenblatt, shows where turnout jumped most and least in 2018, compared to 2014, in Senate District 31.

In Brooklyn’s Senate District 18, progressive upstart Julia Salazar triumphed against Martin Malavé Dilan, who had represented Brooklyn in the State Senate since 2003. Dilan was not a member of the IDC, but the progressive push in 2018 helped fuel Salazar’s campaign, including backing from the Working Families Party and the New York City branch of the Democratic Socialists of America.

Salazar picked up votes in neighborhoods with some of the highest changes in turnout from 2014 to 2018, including East Williamsburg, Bushwick and Greenpoint.

“While the Senate primaries saw dramatic increases in turnout throughout each district from 2014 to 2018, even compared to the gubernatorial primaries, the relative turnout increase was absolutely massive in the areas where progressive primary challengers did best,” said Rosenblatt, of Tidal Wave Strategies, referring to his data and mapping analysis. The map below, created by Rosenblatt, shows where turnout increased the most and least in 2018, compared to 2014, in Senate District 18.

The fight continues

According to Doug Muzzio, a political science professor at Baruch College, campaigns need three things to succeed: money, organization, and message.

“The opponents of the IDC had more of the three than the members of the IDC,” he said, looking back at 2018’s primary upsets.

The odds piled up for dramatically increased voter turnout, and for a turnout against the IDC: the national Democratic movement in response to Trump and for a “blue wave” in the 2018 midterms, accelerated progressive conversations and efforts launched by grassroots organizers, strong upstart candidates, and a concerted plot to educate voters ahead of the election cycle.