A Closer Look at ‘Vital Brooklyn,’ Cuomo’s Plan for ‘One of the Greatest Areas of Need in the Entire State’

Cuomo & Vital Brooklyn (photo: Mike Groll/Governor's Office)

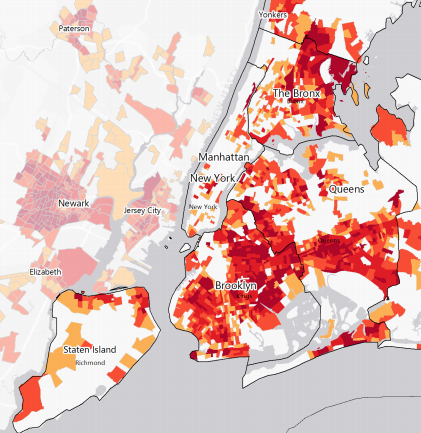

In March of 2017, Governor Andrew Cuomo unveiled what he described as a groundbreaking initiative to “bring health and wellness to one of the most disadvantaged parts of the state.” That place was Central Brooklyn, where roubling health indicators of all types plague residents, from diabetes rates to poverty levels to inadequate access to quality health care.

Cuomo said the plan, named Vital Brooklyn, came with $1.4 billion in state funds to pay for a long list of items across the borough, from playground renovations to job training to resiliency projects — all with the aim of fighting “entrenched pockets of poverty” in a comprehensive way, he said at the time.

“What is the area in this state that has the greatest social need? If you look at unemployment rates, food stamps, physical inactivity, number of murders, one of the greatest areas of need in the entire state is Central Brooklyn. And it’s not even close,” Cuomo said.

Since then, the governor has made nearly a dozen announcements related to Vital Brooklyn, six of them taking place from June to September in the lead-up to this year’s gubernatorial primary in which candidates for statewide offices heavily courted Central Brooklyn voters. At those events, Cuomo emphasized state funding for an oyster reef restoration project ($400,000), 22 community gardens ($3.1 million), fresh food programs ($1.8 million) and a new 407-acre state park to be named after iconic Brooklyn Congressional Rep. Shirley Chisholm — an announcement made eight days before the primary.

In total, the governor’s office says there are 8,800 projects funded under the Vital Brooklyn umbrella, funded by the $1.4 billion (a dollar amount unchanged since spring of 2017, according to the state budget office). However, it’s important to note that those touted by the governor — such as those gardens, farmers markets and state park — make up a small slice of the total funding. The much larger pieces of the pie fall into just two (albeit very big) categories: housing and health care.

In fact, nine out of every 10 dollars spent through Vital Brooklyn fall into the housing and health care columns: $578 million for subsidized housing in rapidly gentrifying areas (for example, a 2,400-unit project just announced in East New York) and $700 million, allocated in 2015, for a new health care system that aims to restructure and revive three of Brooklyn's struggling hospitals.

While some aspects of Vital Brooklyn are quickly taking shape, others will take months or years to materialize. Some officials, including several who have excitedly joined Cuomo at celebratory announcements, are lauding the investments, but critics of the project worry it’s not enough — and take issue with how Vital Brooklyn was rolled out, and how the money is divvied up.

Brooklyn Borough President Eric Adams said in a recent interview that his office wasn’t asked to give input on the project (the state instead took comments from advisory boards convened through the area’s elected state Assembly members) and he feels the funding is too small in scope and dollar amount, even if the governor’s frequent appearances make it appear otherwise.

“We have to have a re-examination of the state allocations and are we doing what’s right by Brooklyn,” he said, particularly in relation to the Bronx, which Adams feels has gotten significantly more financial help from the state; Bronx Borough President Ruben Diaz, Jr. is a close ally of the governor.

Earlier this year, he put it more bluntly earlier in an interview on the Max & Murphy podcast.

“You can’t keep brushing off and rolling out the same billion-dollar project,” he said in May.

When asked to respond to that claim — and whether or not the Vital Brooklyn announcements were made in relation to this year’s primary — Cuomo spokesperson Tyrone Stevens’ comment was brief: “Bogus.”

“This is simple: Our significant new investment in Brooklyn is based on a multi-pronged strategy to uplift communities that have been ignored for too long,” Stevens said in an email. “We’re proud of this effort, and we will not be shy about talking to local residents about the important work we’re doing to make their neighborhoods a better place to live.”

Big Spending: Health Care

Of Vital Brooklyn’s $1.4 billion, fully half is dedicated to a new health care system for Brooklyn. That funding comes from a $700 million capital grant made through the Health Care Facilities Transformation Program included in the 2015-2016 state budget, allocated two years before it was announced as part of Vital Brooklyn.

The funding will go to One Brooklyn Health System (OBHS), a newly formed operator that will combine the management of three previously separate Central Brooklyn hospitals — Kingsbrook Jewish Medical Center in East Flatbush, Interfaith Medical Center in Bedford-Stuyvesant, and Brookdale University Hospital Medical Center serving Brownsville and East New York — into one not-for-profit corporation.

LaRay Brown, previously the president and CEO of Interfaith, is heading up the new venture. She says she’s been pushing for years for the “incredibly impactful” amount of state funding that will support dozens of major projects throughout the new health care system.

Inside the buildings, the $700 million will pay for “boring things, but essential things,” Brown said, like replacing elevators, repairing HVAC systems and updating an outdated fire alarm system.

“I say they’re boring, but they’re critical to providing safe and comfortable patient care,” she said.

The medical centers will get major upgrades to their patient facilities, too. According to Request for Proposal documents from OBHS, Brookdale will build out a new 33-bed intensive care unit, renovate a 40-year-old operating room suite and upgrade all of the facility’s inpatient psychiatric units among others improvements. At Interfaith, the medical center’s emergency room will be upgraded and expanded, inpatient medical units will be renovated and new equipment such as MRI and x-ray machines will be installed. Major medical equipment will be replaced at Kingsbrook, as well, the documents show.

Overall, the idea for the restructuring and redesign is to merge services among the three hospitals in order to form a more streamlined organization — and hopefully, in the end, become more financially stable.

That’s according to state officials from the Public Health and Health Planning Council who approved the creation of OBHS in December of 2016. A report to the council at the time concluded that, operating separately, the hospitals require hundreds of millions of dollars in operating subsidies from the state every year “and are otherwise not financially sustainable.” (According to budget data from a PHHPC report, operating funds given to the three hospitals from the state totaled $169 million in 2015-16, then rose to $245 million in 2016-17 and $250 million in 2017-18.)

“They've come together … in an effort to try to restructure and become more efficient and reduce its dependence on specialty subsidies,” state health department official Charles Abel told the council before it approved the OBHS application.

To achieve those efficiencies, OBHS will reorganize how certain operations run within the three hospitals. For example, Brown said, Kingsbrook will no longer have inpatient medical-surgical beds and, though it will still have an emergency room, patients in need of ongoing acute or complex care will be transferred elsewhere, likely to Brookdale, which Brown said will become the system’s “center of excellence.”

“As the inpatient acute care role diminishes at Kingsbrook, that role increases at Brookdale,” said Brown (pictured).

“As the inpatient acute care role diminishes at Kingsbrook, that role increases at Brookdale,” said Brown (pictured).

But Brown is careful to note the restructuring effort should not be considered a consolidation. Current assessments by OBHS show no material difference between the number of current beds and projected beds in the system, according to OBHS’ Dona Green. In the end, Brown says the quality and quantity of services will expand.

“Because these hospitals are coming together and because of the state’s commitment to invest in these hospitals, the Central Brooklyn community served by these hospitals will get more services, and not less,” Brown said.

That sentiment was echoed by Assemblymember Latrice Walker of District 55 in Brownsville, who has been waiting for years to see this funding come through for the hospital system, particularly at Brookdale, where many of her constituents go for care — and where her own brother died of gunshot wounds when he was 19, she said.

“I’m confident the services will be reinvigorated and enumerated. I don’t think we’re going to lose anything here,” she said. “Quite the contrary — we’re actually gaining.”

By the totality of the health facilities in the works under Vital Brooklyn, that appears to be the case. A chunk of the initiative’s healthcare funding — $210 million in all — is allocated to create 32 new ambulatory care facilities, or community health centers, under the OBHS umbrella. The goal there is to create more medical offices, outpatient surgical facilities and urgent care options with a more long-term goal of reducing unnecessary trips to emergency rooms.

“We need to start moving toward people having primary care physicians so that the emergency room isn’t their doctor office,” Walker said.

Cuomo put it this way when announcing some of the 32 ambulatory care locations in July of this year: “It's not just about a hospital where you go when you're very sick.”

“Prevent the illness in the first place,” he continued. “Have more community-based healthcare systems that are focused on wellness, and health, as opposed to waiting for a person to get sick, and then be in acute need.”

These new ambulatory centers are meant to handle a diverse slate of same-day health services, including diagnostic work, rehabilitation, or even major procedures such as hip replacements, according to Bill Hammond, the Director of Health Policy at the Empire Center think tank.

Ambulatory centers have a lot of benefits, he said. For the patient, it’s generally a more comfortable experience to avoid spending a night at a hospital, and there’s less risk of infection. For hospitals, increasing outpatient services makes a lot of financial sense.

“It’s less expensive,” he said. “Hospitals come with a lot of overhead.”

That idea is in line with a healthcare trend more generally to move patients out of traditional inpatient hospitals and toward ambulatory centers for all kinds of services, from preventative doctor visits all the way up to certain surgeries. The move from “reliance on hospital-based services” to more outpatient services “is a major policy shift,” said Brown of OBHS. And it takes place within the context of years of financial struggle, and at times closure, for many hospitals, particularly those serving low-income communities, as costs have continued to rise.

To combat that, the Vital Brooklyn plan puts a priority on the financial viability of health care projects funded under the plan. Included in guidelines for evaluating applicants to Vital Brooklyn, the state’s website says it will consider “the extent to which the proposed projects further the development of primary care and other outpatient services; the extent to which the proposed projects contribute to the long-term sustainability of the applicant or preservation of essential health services; and the extent to which the proposed projects involve partnerships with community-based health care providers,” among other criteria.

With the funding for the new 32 health facilities, the state hopes to roughly double the number of ambulatory care visits in Central Brooklyn, increasing capacity for 742,000 more visits every year, according to the governor’s office.

Exactly where all that new health care capacity will be built is unknown; all 32 locations have not yet been finalized. But Cuomo announced plans in July for renovations and the expansion of several existing health care centers, including the Bishop Walker Health Care Center in Prospect Heights, the Pierre Toussaint Health Center in Crown Heights and the Brownsville Multi-Service Center. In addition to those locations, several health care providers including the Bed-Stuy Family Health Center, Community Health Network, and ODA Primary Health Care Network have been chosen by the state to build new health centers in Brooklyn, providing both primary and specialty care.

Some of the 32 new ambulatory health centers will be built within new developments underwritten by the second largest piece of the Vital Brooklyn funding: affordable housing.

Housing on State and Hospital Sites

In all, the state will spend $578 million — or more than 40 percent of the total Vital Brooklyn package — on subsidized housing, with a goal to build 4,000 new units over several years.

The governor has repeatedly linked overall health goals of Vital Brooklyn to housing, particularly in rapidly gentrifying areas such as East New York where speculative buying and building, combined with a 2016 rezoning, has put pressure on poor residents.

“It starts in the home, having the right housing, having the right environment, having the right support. And that's where we're going to start. We need afford affordable housing because out people are being displaced. Gentrification is everywhere,” the governor said at a Vital Brooklyn event earlier this year.

How all those units will be constructed is still up in the air, but details on some of the development sites are beginning to emerge. Late last month, the state announced four winning bids to develop housing on land owned by the three OBHS hospitals or on state-controlled land, including one complex in East New York that’s set to deliver the bulk of the subsidized housing funded under Vital Brooklyn.

On Nov. 29, the state chose Westchester-based L+M Development Partners, Harlem-based construction group Apex Building, and two social services organizations — RiseBoro Community Partnership and Services for the Underserved — to bring a massive, 2,400-unit development to the site of the former Brooklyn Developmental Center, a home for developmentally delayed adults that closed in 2015. The three other chosen projects — two to be built on land owned by Interfaith hospital and another on land owned by Brookdale Hospital — will bring another 328 subsidized units to the borough.

At the same time the state announced those projects, it rolled out another set of request for proposals (RFPs) on eight state-controlled sites around the borough, including several hospital parking lots set to be replaced by new buildings. Proposals for five of the sites are due by February 28, 2019 and the three others are due by April 30, according to the RFP documents.

A majority of the affordable housing will be funded by $568 million allocated through the state’s Homes and Community Renewal agency, with a goal of creating 3,000 units. In addition, the governor said in August $15 million in federal tax credits have been allocated by the state for future housing developments on land controlled by the New York City Housing Authority (NYCHA). In his announcement on that initiative, the governor said he hopes to support the creation of 1,000 units of housing. However, no specific sites for those developments have been announced and will be “reviewed on a rolling basis by HCR as NYCHA makes properties available through its disposition process,” according to a press release.

The need for housing is the number one priority for Brooklyn residents, Borough President Adams said, and he gave credit to Vital Brooklyn for addressing the issue. He also acknowledged the plans would bring much-needed resources — including park space and options for healthy food — to the area. But he thinks it doesn’t go far enough.

“We’re dealing with historical inequities. People who were denied food access before — OK, let’s give them more farmer’s market,” he said. “Those things are great. But if we’re going to invest, let’s be visionaries in our investment.”

He would have liked to see more funding allocated to grandparent housing, which is set aside for grandparents who are the primary caregivers to young children, and even more resources given to the hospital network, he said.

More criticism of the governor’s Vital Brooklyn plan came from the East New York district where the large Brooklyn Developmental Center site is set to be rebuilt under the initiative. The complex will have 100 percent subsidized apartments set aside for a combination of formerly homeless New Yorkers, households earning less than 50 percent of the area median income (AMI) — a federal guideline for determining the cost of affordable housing — and the rest for households earning less than 80 percent of the AMI. Currently for a family of three, 80 percent of AMI equals $62,150 a year.

That may sound like a win in a low-income area like East New York. But with the median household income of East New York at $34,512 per year (according to data from the city’s Housing Preservation and Development agency), the development doesn’t satisfy one of the neighborhood’s longtime leaders.

Assemblymember Charles Barron says his district needs even more low-cost units because only a fraction of its residents are in the 80-percent income range. And, overall, he thinks Vital Brooklyn doesn’t go far enough in a state with a $168 billion budget, and billions more in capital spending.

“You see $600, $700 million and think it’s wonderful and a lot of money,” he said. “That is peanuts.”

In particular, he wants to see more support for the healthcare system.

“It’s simply not enough money for three hospitals,” he said.

In response, Cuomo spokesperson Stevens said in a statement that the Vital Brooklyn investment is “delivering substantial resources and coordinated services to support neighborhoods that have long been neglected.”

“We believe this massive commitment is something to celebrate, not politicize with cheap attacks that are untethered to reality,” he said.

Looking for Results

The governor has often said, for him, Vital Brooklyn is a project that brings his own career full circle, from when he was working on housing in East New York as a young man, to now. In speaking about it, he says he has wanted to help turn Brooklyn around for years.

“I never lost the inspiration, and the hope, and the optimism, of what you can do when you do it right,” he said in a speech on the project in April, nearly half-way through his eighth year in office. “For me, this is something special. This is something that is long overdue. It's an investment in people who desperately have needed help, and have been ignored for too long.”

“I never lost the inspiration, and the hope, and the optimism, of what you can do when you do it right,” he said in a speech on the project in April, nearly half-way through his eighth year in office. “For me, this is something special. This is something that is long overdue. It's an investment in people who desperately have needed help, and have been ignored for too long.”

But it may take quite a while to see all of the Vital Brooklyn projects come to life. Some of the smaller pieces of the puzzle, like a pilot program for youth-run food markets and construction on new playgrounds, are beginning this year and next, the governor has said. For the larger, more complicated parts, however, it could take years; for example, some of the first units of housing are estimated to come online in 2021 and others — like the East New York project — is not slated for completion until 2026, the governor’s office said.

The health center restructuring, too, will takes years to finish. When it’s finally complete, it remains to be seen whether the largest part of Vital Brooklyn — the $700 million in health care capital funding — will make a substantive difference to financially shore up the three Central Brooklyn hospitals.

Hammond of the Empire Center said if the plan is a good one that reconfigures the facilities’ operations significantly, it “could put them in a different position to succeed,” though he was hesitant to say whether he believes the restructuring will prove successful long-term.

But the health funding is not peanuts, as Barron said, nor is it a groundbreaking amount, as one may think from the governor’s announcements. The reality is somewhere in the middle.

“The state routinely spends billions and billions of dollars on health care all over the state,” both in discretionary grants and capital allocations, Hammond said. “On any given day, you could go to a different community and announce a very large-sounding dollar amount…and it would be absolutely routine.”

However, on a per-resident basis, Brooklyn is getting more than the average — while falling far below the state’s most generous allocations. Hammond found the state spent $190 per resident in capital health care spending in the last five years in New York State. In Kings County, the per-resident breakdown equaled $264 per resident, which is “significantly more than the state average,” he said. But that figure is dwarfed by another capital grant also given in 2015 to a hospital system in Oneida County, where spending totaled $1,297 per resident.

For all those funding plans, however, the dollars have not yet started to flow, according to Brown of OBHS. Before that happens, several bureaucratic steps must take place, including complying with transparency regulations approved by the state comptroller’s office. She hopes that will be complete in the new year.

“Everyone is endeavouring to get [approval]…by early 2019,” she said, while emphasizing it’s hard to make an exact estimate, as she and her team are figuring out the complexities of the project as they go along.

“We’re all entering a new journey here,” she said.

***

by Rachel Holliday Smith for Gotham Gazette

@rachelholliday

@GothamGazette

All photos via the Governor's Office on flickr.

Max & Murphy Podcast: Will Single-Payer Health Care Come to New York?

Ben Max, left, of Gotham Gazette, and Jarrett Murphy, right, of City Limits

December 12, 2018 - Max & Murphy Podcast: Will Single-Payer Health Care Come to New York?

One of the most hotly-debated issues in state government is whether New York should or will move ahead with the New York Health Act, which would institute single-payer health care. State Senator Gustavo Rivera, a Bronx Democrat, is the Senate sponsor of the bill and will soon be part of the Democratic majority in the Senate, as well as the health committee chair. He joined the show to discuss the broader priorities of the Senate Democrats and the prospects for the New York Health Act when his party has full control of state government come January.

One of the most hotly-debated issues in state government is whether New York should or will move ahead with the New York Health Act, which would institute single-payer health care. State Senator Gustavo Rivera, a Bronx Democrat, is the Senate sponsor of the bill and will soon be part of the Democratic majority in the Senate, as well as the health committee chair. He joined the show to discuss the broader priorities of the Senate Democrats and the prospects for the New York Health Act when his party has full control of state government come January.

Then, Bill Hammond, director of health policy at the Empire Center, joined the show to dissect the New York Health Act and a variety of ways in which he thinks it is problematic legislation, as well as the political terrain ahead for it.

Listen to the conversation and let us know what you think -- we're on Twitter @TweetBenMax and @JarrettMurphy. You can listen to the show through the embedded audio below or download the episode wherever you get your podcasts, under "Max & Murphy," and listen to Max & Murphy live on Wednesdays at 5 p.m. on WBAI radio, 99.5FM or wbai.org

***

by Ben Max, Gotham Gazette

@tweetBenMax @GothamGazette

‘It’s just not designed to do its job’: Will New York reform its state ethics agency?

Skelos, Cuomo & Silver in 2011 (photo via the Governor's office)

This year’s elections in New York saw the issues of public corruption and government ethics reform take centerstage in several campaigns. Insurgent Democratic candidates, some who succeeded and others who did not, challenged incumbent elected officials on their parts in the broken system of corruption prevention and ethics enforcement at the state level that has allowed -- some say encouraged -- rampant corruption and self-enrichment.

Much criticism has been levelled at the state’s Joint Commission on Public Ethics, or JCOPE, a relatively young agency with a lackluster record of keeping watch on wrongdoing in state government. Since the agency’s inception seven years ago, several sitting lawmakers have been indicted and convicted of public corruption. But in most, if not all, those cases, JCOPE seems to have sat idly by as other enforcement agencies eventually stepped in. JCOPE has brought enforcement actions for ethical violations against only two lawmakers in that time -- one in 2013 against former Assemblymember Vito Lopez and then in 2015 against former Assemblymember Dennis Gabryszak. The body does not appear to many as much of a deterrent or enforcer.

Now, with Democrats set to take full control of the state Legislature and legislative leaders signalling a renewed commitment to reform, there’s talk of altering, or even repealing and replacing JCOPE, with some reform-minded legislators eyeing their new opportunity and even some relevant campaign season words from Governor Andrew Cuomo about making the ethics body more independent. Among them are Assemblymember Tom Abinanti, who wants to reform the agency’s membership, and State Senator Liz Krueger, who has proposed eliminating JCOPE and creating an entirely new agency from scratch.

Good government advocates are pushing for a soup-to-nuts reimagining of ethics enforcement. At minimum, they say, there should be changes to how JCOPE commissioners are appointed and that the agency should be given more teeth. The best-case scenario? Do away with JCOPE entirely and replace it with an entity as close to completely independent of political interference as possible.

JCOPE was created in 2011 during Cuomo’s first term, after he came into office promising to wipe clean the rot that had infected state government. Part of a deal with a hesitant Legislature, the agency was charged with overseeing lobbying activities and ethics violations by members of the state Assembly and Senate, the executive branch, dozens of state agencies, and candidates for elected office. It’s composed of 14 commissioners who serve five-year terms -- six appointed by the governor and lieutenant governor, three appointed by the Assembly speaker, three appointed by the Senate majority leader, and one each appointed by the minority leaders in both legislative chambers. The governor also appoints the chair of JCOPE while its executive director is chosen by the commissioners.

To advocates, JCOPE’s structure is plainly at the root of its problems. “The fundamental problem is, if you don’t have independent enforcement of the law, it doesn’t matter how good the laws are,” said Blair Horner of the New York Public Interest Research Group. “While that’s not a bumper sticker issue, it’s not the sexy ethics issue to talk about, it is the critical one. The cornerstone of effective ethics enforcement is the independence of the agency that deals with it.”

Advocates and reform-minded elected officials have argued for years that JCOPE commissioners cannot be expected to conduct robust investigations of the very institutions, entities, and individuals that appoint them. JCOPE’s current executive director Seth Agata, a former aide to Cuomo, was a particular target of that criticism during the election. Cuomo’s Republican opponent, Dutchess County Executive Marc Molinaro, repeatedly called on Agata to step down over having failed to adequately scrutinize the executive chamber, particularly after the corruption conviction of Joe Percoco, a former top aide to Cuomo, who was found to have used his executive chamber office while working on Cuomo’s first reelection campaign.

In their only debate of the race, even Cuomo conceded that he would prefer to see a more independent JCOPE. “I believe we need more independence on JCOPE, I believe we need totally independent appointees and not necessarily representatives of both houses [of the Legislature],” he said. “I’d be open to a number of configurations, but they’d have to be independent. I’d have the attorney general involved; I’d have the chief judge involved in appointing the members.”

As he often has, Cuomo indicated his belief that even getting the Legislature to agree to creating JCOPE was a significant lift, and he added that it provided an opportunity to push further, having cracked the door open.

In the Democratic attorney general primary race as well, Fordham Law professor and anti-corruption crusader Zephyr Teachout led the charge in calling for Agata’s resignation, inflamed in part by JCOPE’s investigation and subsequent clearing of Sam Hoyt, a former state economic development official who was accused of sexual harassment and assault by a woman who said he helped her obtain a job at the state DMV. Hoyt was previously a long-serving member of the Assembly and was also investigated for sexual harassment while in office, and was later disciplined for having an inappropriate relationship with an intern. He was recruited after that by the Cuomo administration.

Public Advocate Letitia James, who went on to win the attorney general seat, initially took a softer position on JCOPE but eventually too joined Teachout in calling for Agata to step down, as did Rep. Sean Patrick Maloney, who was also in the race. Former Verizon executive Leecia Eve, who worked with Agata in Cuomo’s administration, was the only Democratic attorney general candidate not to issue that demand but did say that JCOPE should be scrapped and a new agency created from the ground up.

[Read: Agenda 2019: High Hopes for Long-Awaited Reforms]

There have been bills introduced in the state Legislature that would accomplish these goals. Earlier this year, Assembly Member Tom Abinanti, a Democrat representing parts of Westchester County, proposed restrictions to JCOPE’s membership. His bill would prohibit an individual from serving on the commission if they had been a registered lobbyist, elected official, state officer or employee, or a legislative employee within the previous ten years. “We should ensure that no member of JCOPE is inclined to act preferentially for or prejudicially against any subject of a JCOPE inquiry,” Abinanti said in a phone interview.

Abinanti said he was open to the idea of potentially scrapping the agency but said his bill was a necessary half-measure in the absence of broader action. “My bill is a more practical approach that, so long as we have JCOPE, we have to make some reforms and we need to make sure that the members of JCOPE do not have any relationships with the people who might become the subjects of their inquiry,” he said.

The office of Assembly Speaker Carl Heastie, a Bronx Democrat, did not respond to a request for comment. Senate Democratic spokesperson Mike Murphy said, “There was much done by the previous majority in furtherance of Senate Republicans’ partisan agenda and we expect to reform those inequalities to create more fairness,” likely referring to the fact that the Senate Republicans will still maintain control of a majority of the chamber’s appointments to JCOPE even after Democrats take the majority.

Good government advocates agree that, in the absence of a new independent agency, the Legislature should make fixes to JCOPE’s problems, which are many. Besides the perceived conflicts of interest in appointments, the agency is notoriously opaque to the public. It does not release the details of investigations or even say whether an investigation has been initiated or concluded, for which it was recently sued by New York State Republican Party Chair Ed Cox. Its bizarre rules also effectively allow three Republicans out of the 14 members to block a majority vote for an investigation to proceed into a state elected official, said Alex Camarda, senior policy advisor at Reinvent Albany. The law mandates that the majority vote must include “at least two members appointed by the governor and lieutenant governor and enrolled in the individual's major political party, if he or she is enrolled in a major political party.”

“That’s probably the greatest flaw with JCOPE,” Camarda said. And, owing to how the original JCOPE law was written, both parties also retain the number of appointments they can make even if they are not in the majority in a legislative chamber.

“There’s tweaks and adjustments to the current structure or there’s scrap the whole thing and start over,” said Camarda. “The best practice is to start with a nominating pool from which elected officials choose and the candidates that are put into the nominating pool would be put there by an outside body like the City Bar Association or judges, people who are unaffiliated with the targets of ethics investigations.”

Senator Krueger, a Manhattan Democrat, agrees with that sentiment and has proposed a state constitutional amendment to create that independent entity.

Krueger introduced a resolution, co-sponsored by Assembly Member Robert Carroll, a Brooklyn Democrat, at the tail end of the 2018 legislative session that would add a new article on state government integrity to the constitution. It would establish a New York State Commission on Government Integrity to take over the role currently played by JCOPE. The new commission would be made up of nine members -- two appointed jointly by the governor, attorney general and comptroller; five appointed by the state’s chief judge and the presiding justices of the appellate courts; and one each by legislative conference leaders of political parties that are the top-two vote getters in the previous gubernatorial election.

Pursuing a constitutional amendment would also remove Governor Cuomo from the process. Unlike a bill that he could choose to sign or veto, the amendment would have to be approved by both legislative chambers in two consecutive sessions and then be presented to voters as a ballot measure.

“So do I assume [the governor] wouldn’t like this? Yes, probably he wouldn’t like this,” said Krueger, who will be a powerful member of the incoming Senate majority. “He wrote the existing JCOPE language. I don’t think that current model is working and I think we need to fix that...It’s just not designed to do its job.”

Krueger plans on reintroducing her resolution in the upcoming legislative session in January, with a few changes, which her office shared with Gotham Gazette, after consulting with the state’s chief judge and attorney general’s office. The earlier version allowed the commission to remove a legislator from office but the new version does not give the body that authority. Another revision allows the commission to give informal advice, which can then be used by an individual as defense in any potential future investigation.

The bill hasn’t been discussed yet by Senate Democrats and Krueger said it isn’t on the list of priorities for the conference as it meets this week to prepare for January. But Krueger is particularly optimistic that the Legislature will be under added public pressure after this election to move ahead on ethics reforms, both preventative and in enforcement. “I always have said, never waste a good crisis in government,” she said, “and when people have serious doubts about the honesty and integrity of their government leaders, it is a serious problem for all of us.”

She continued, “We depend on federal prosecutors to come in and play gotcha with us to finally get anything done. I’m not opposed to federal prosecutors playing gotcha, I just think the state of New York ought to have a system in place that can self-police, that can investigate, that can find people innocent when wrongfully accused and direct those, where there are findings of bad behavior and guilt, that those people be referred to the appropriate people in criminal justice.”

Another area where JCOPE is thought to be unequipped is in examining allegations of sexual harassment, an issue brought into recent relief by the allegation of forcible kissing brought against Senator Jeff Klein by a former aide, Erica Vladimer. Not only is it unclear if JCOPE has the expertise to examine sexual harassment claims, but there is little transparency related to any investigation that may or may not be happening, nor clarity around whether an accuser is provided information about the status of an investigation.

JCOPE spokesperson Walter McClure declined to comment on the proposals put forward by Krueger and Abinanti. “Any decisions on changes to our enabling legislation or the laws that we have oversight over are up to the Legislature and the Executive,” he said in an email.

It’s unclear whether the governor will back these efforts. On government ethics reform he has a history of promising big but delivering small, something that has left critics wary. As Camarda noted, “The governor told the editorial board of the Daily News that he was going to put into place a database of [economic development] deals, which he could do via executive order or pass legislation. He has not done that.” He also cited Cuomo’s unfulfilled promise to restrict campaign contributions from vendors bidding on state contracts.

The governor also made promises to pursue campaign finance reforms, including closing the so-called LLC loophole, and has repeatedly emphasized banning outside income for legislators as a sweeping ethics solution, even when the corruption has touched his own inner circle, removed from the Legislature. He lauded the recent recommendations of a state panel that would give lawmakers a pay raise while severely curtailing the money they can make from outside sources. Cuomo has been less vocal, however, about the issues within his own administration as highlighted by the scandal-ridden Buffalo Billion economic development program.

The governor’s office also did not provide any concrete proposals for reforming JCOPE when asked for comment. Hazel Crampton-Hays, a spokesperson for the governor, said in an email, “Governor Cuomo will continue to lead the fight on ethics reform to restore confidence in government, and we look forward to engaging with the new legislature to update and refine our laws and identify which new reforms will be most effective.”

***

by Samar Khurshid, senior reporter, Gotham Gazette

@samarkhurshid @GothamGazette

On Census Preparations, State Lags While City, Advocacy Organizations & Business Community Move Ahead

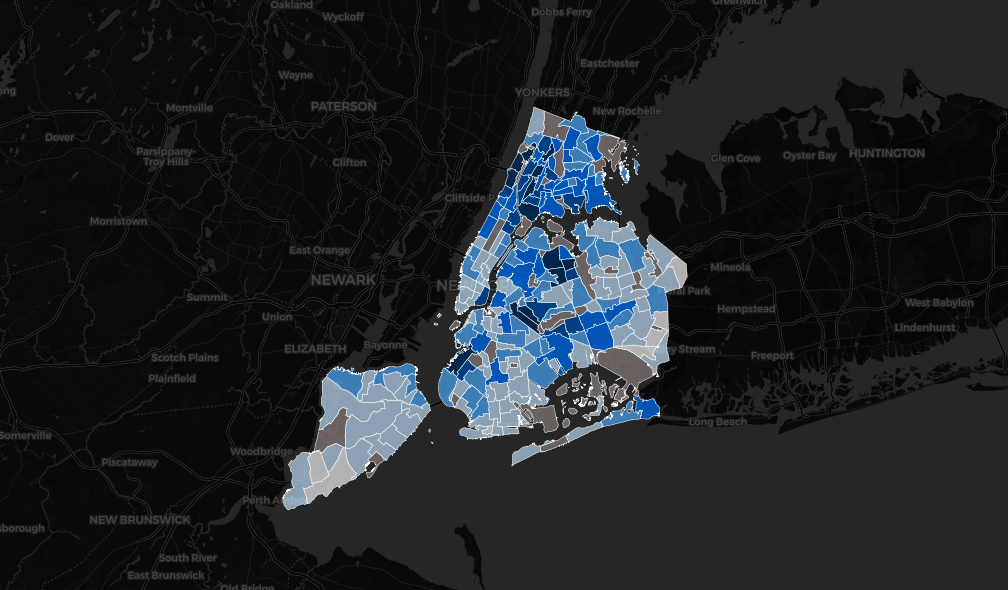

(image via New York City's City Planning Department)

This is part of AGENDA 2019, a joint Gotham Gazette-City Limits project

Find the rest of the series here

“It might seem early, but given the challenges that are facing the decennial census in 2020, it’s not early enough,” said Steven Romalewski, director of the mapping service at the Center for Urban Research, CUNY Graduate Center. Advocates, government officials, and members of the business community all agree with that sentiment, that early preparation is essential if New York is to ensure a full accounting of its population in the 2020 Census, wherein the stakes are immense.

The census, the federal government’s constitutionally required every-ten-year count of residents of the United States, forms the basis for each individual state’s electoral representation, both locally and at the federal level, determines levels of federal funding states receive each year, and underpins dozens of human-facing programs carried out by state and local governments. Officials and advocates in New York City have already begun to marshall resources as they prepare for the nearly two-year effort that lays ahead, but the state has yet to pick up its feet despite a looming deadline.

Many view 2020 as a particularly challenging year for the Herculean effort of carrying out the census. Besides the usual logistical challenges of reaching hard-to-count communities, 2020 is set to see lower-than-expected funding from the federal government, a shift towards digital methodology, and the inclusion of a citizenship question, though it is the subject of ongoing litigation spearheaded by New York Attorney General Barbara Underwood. All that comes amid a heightened atmosphere of anxiety among minority and immigrant communities who fear the repercussions of being counted by a federal administration overtly hostile to their interests while already being most likely to be undercounted.

In each census, the federal government has to work hand-in-hand with local counterparts to reach hard-to-count communities, those where at least a quarter or more of households do not fill out the initial census questionnaire sent out by the Census Bureau. In New York State, 75.8 percent of households responded to the 2010 census, according to estimates by the CUNY Graduate Center, which worked with civil rights organizations across the country to create maps of census tracts to identify hard-to-count communities. The rest must then be counted in person by the thousands of enumerators hired by the Census Bureau, a labor- and time-intensive process that includes a lot of door-knocking and also requires additional resources and funding.

Advocates and experts warn that the Trump administration’s underfunding of the Census Bureau and attempt to include a question about citizenship may lead to a grossly inaccurate count, the effects of which will be felt for the better part of the decade before the next census in 2030 and could hit New York, especially New York City, particularly hard. An undercount can cement the problems faced by the most vulnerable members of society -- seniors, children, the homeless, for instance -- and exacerbate them by creating a false dataset based on which government crafts policy and budgets.

City officials already recognize these challenges that lay ahead. Deputy Mayor for Strategic Policy Initiatives Phil Thompson is leading the de Blasio administration’s broad census outreach efforts, coordinating with partners in state government, community-based organizations, and the private sector, which is particularly involved in the current census cycle. Thompson pointed to two main outreach targets: immigrant communities and black communities.

“In immigrant communities, it’s always a challenge to get a good count in New York City because it is so diverse,” Thompson said in a phone interview. “There are so many immigrant communities, which people may not even hear about sometimes. [The questionnaire is] not in their language. They’re new. They get skipped.”

The Census Bureau currently only translates its questionnaire into about 20 languages, he said, and New York City residents speak more than 100. The city has already allocated about $4.3 million to its census efforts in the current fiscal year, ending June 30, 2019, which will be used to conduct outreach through ethnic media, Thompson said.

But the bigger fear among the large undocumented immigrant population that resides in the city is that census answers may be passed on to immigration enforcement authorities, even though that is prohibited under the law. “Now, the law prohibits passing information on from the census to any other agency and individual data is not allowed to be passed on, but folks are scared anyway,” Thompson said.

But the bigger fear among the large undocumented immigrant population that resides in the city is that census answers may be passed on to immigration enforcement authorities, even though that is prohibited under the law. “Now, the law prohibits passing information on from the census to any other agency and individual data is not allowed to be passed on, but folks are scared anyway,” Thompson said.

[pictured: New York City census hard-to-count map, via CUNY Graduate Center Mapping Service]

Black communities, the other main target of the city’s efforts, have had historically low rates of filling out the census, Thompson noted. “That goes for people who live in public housing or in low-income housing. Many people may have an extra person living in the house and they’re afraid that the census comes and does a count of who’s in the household, they may get in trouble...And then some mysteries. We don’t know why middle-income and upper-middle income black people in Southeast Queens don’t fill out the census, but historically they’ve had low rates as well.”

2020 will also mark a major shift in how the census is carried out, with a greater reliance on digital technology. As opposed to the past method of sending out the questionnaire by mail, the Census Bureau will send out a digital code by mail, encouraging people to fill out the questionnaire on the Census Bureau’s website.

When people do not respond, they will be sent a full paper questionnaire to mail back. People can still request a paper questionnaire, particularly if they lack easy access to the internet. “And that’s a challenge because not everybody utilizes iPads and computers,” Thompson said. “Not everyone’s on the internet. So in communities with low broadband access, they are more likely not to fill out the census.”

In response, the city plans to set up help desks at public libraries and schools to facilitate access, with several public-facing city agencies such as the Department of Education and Department of Homeless Services also involved in the effort. The de Blasio administration is encouraging the private sector to provide financial assistance to community organizations and will also put more funding into hiring immigration lawyers at immigrant affairs offices. The city will also hire 13 district office directors to match the 13 offices being set up by the Census Bureau across the five boroughs, and is helping recruit for the 20,000 or so enumerators that the Bureau will hire to conduct door-knocking and outreach in hard-to-count communities in the city. According to the Bureau’s estimates, they will need roughly 44,442 enumerators for the entire New York region. There are also jobs under the city’s Summer Youth Employment Program focused on democracy and the census, training young people between the ages of 16 and 24 to organize in their communities.

“We’re also telling people if you don’t like what’s going on in terms of a lot of this anti-immigrant rhetoric and so forth, the best thing to do is to not go and hide in the shadows but stand up and be counted,” Thompson said, touching upon the challenge involved in convincing people already wary of the Trump administration to trust that administration’s census process.

Community advocates, in particular, are aware of the pressing need to ensure an accurate count. Liz OuYang, coordinator of New York Counts 2020, a statewide coalition of community organizations, said the upcoming census would be a “heavy lift” compared to 2010. “More than ever, community-based organizations are going to be needed as trusted organizations that people can go to in light of the political climate,” she said. These groups are particularly vital in reaching undocumented immigrants who are fearful or skeptical of the federal government.

Ahead of the 2010 census, community organizations in New York City received only about $2 million in total from private sources, OuYang said, leading to an undercount. This time around, the coalition is pushing the city and state to fund phone-banking and door-knocking operations. They are urging legislators to agree to that demand and plan to rally in Albany, the state capital, in March, ahead of the passage of the state budget.

The coalition is also aiding local Complete Count Committees, including by creating a census training webinar for the committee recently launched by Brooklyn Borough President Eric Adams and the Brooklyn Community Foundation. “Because of the undercount in 2010 and because of the macro-political climate that we’re in, and the census being allowed to be completed online, you’re going to need a lot of help from community-based organizations,” OuYang said.

The federal government appropriated about $2.8 billion for the Census for the 2018 fiscal year, which ended September 30. But the Census Bureau has requested only about $3.8 billion for the 2019 fiscal year, which most experts and stakeholders believe is inadequate. Across the country there are expected to be 200,000 fewer enumerators, who conduct the on-the-ground follow up, because of the lower funding. What’s more, unlike past census efforts, the federal government appears unlikely to approve a waiver that would allow the Commerce Department to hire non-citizens to act as census enumerators in order to reach hard-to-reach communities. Such a waiver was approved by the administrations of Presidents Barack Obama and George W. Bush.

“We don’t know if Trump will do a waiver and if not that’s a problem,” said Deputy Mayor Thompson. “So we’ll have to lean in as a city to get the right people because the most trusted messengers in communities that are fearful are people from the communities.”

In an email, Census Bureau spokesperson Kristina Barrett said the agency was working within the restrictions of the annual appropriations act. “There is not a ban, and we are still pursuing all legal flexibilities provided by Congress to hire the workforce we will need to conduct an accurate 2020 Census,” she wrote. She said the Bureau is allowed to temporarily employ translators under certain exceptions and can hire permanent legal residents applying for U.S. citizenship, people admitted as refugees or granted asylum who have filed a declaration of intent to become a permanent resident and then a citizen when eligible.

To make up for the expected shortfall in enumerators, particularly in undocumented communities, the New York Counts coalition is pushing the state government to ensure adequate funding for counting efforts. A study from the Fiscal Policy Institute, commissioned by the coalition, estimated that need at about $40 million, roughly $2 for each of New York’s 19 million residents. But so far, the state has made no commitment while the city’s $4.3 million is something, but far from adequate. (The city is expected to add more funding in the next fiscal year which begins July 1, 2019.)

“Without funding, community-based organizations are not, that’s the bottom line, are not gonna be able to do full outreach,” OuYang said. “And it takes community-based organizations, trusted organizations in the community to really mobilize people and be the bridge here.”

In the current fiscal year, Governor Andrew Cuomo and the state Legislature approved the creation of a New York State Complete Count Commission, which is meant to study past undercounts and issue a comprehensive action plan for 2020 by January 10, 2019. But with just over a month till its report is due, that commission has yet to be formed, raising concerns that the state is dragging its feet. “I think that the governor needs to prioritize this, this is huge,” OuYang said.

A spokesperson for Cuomo said in an email that the commission is in the final stages of being assembled but did not provide any personnel details or proposed budget numbers. “A complete and accurate count is critical for New York to receive proper representation in Washington and our full allocation of federal funding, and the State is committed to being a full partner in a robust outreach effort so that every New Yorker is counted,” the spokesperson said.

The state has, however, been using data analytics to ensure that the Census Bureau’s Master Address File, which will dictate where the initial census questionnaires are sent in March 2020, is complete. According to the governor’s office, addresses in the MAF were compared to state databases and agency records and hundreds of thousands of corrections and additions were submitted to the Census Bureau for review this past summer. There have also been 40 meetings across the state to encourage the creation of complete count committees.

It’s likely that the governor will provide more clarity about the overall census effort in January at his State of the State speech, where he will lay out his broader agenda for the year. His executive budget proposal with funding numbers will follow soon after.

Thompson, the deputy mayor, said he was optimistic about the state coming through and that operations will likely ramp up with the start of the new year. In the meantime, New York City government and members of the business community are picking up the slack.

“So far New York State hasn’t put up a [funding] number and we were actually helping other towns and cities in New York organize their census operations because the state commission on the census hasn’t met yet,” Thompson said. “We’ve had nice conversations and I’m looking forward to working with the state around this, but right now we’re, I think it’s safe to say, ahead of the state.”

He noted that the New York Banker’s Association had offered to make its locations available to get the word out about the census. “I’m most excited about the responses we’re getting from every sector of the city to come together,” Thompson said. “The business community is very forthcoming.”

The Association for a Better New York, a prominent business coalition in the city, announced on December 3 that it had hired Melva Miller, who was previously deputy borough president of Queens, to lead its census efforts, the broad contours of which had been announced previously. “This is an all hands on deck effort,” Miller said in a phone interview.

ABNY has been marshalling resources for nearly a year to assist New York’s efforts. It has been conducting focus groups in hard-to-count communities, gathering data and information on the obstacles people may face. It also launched a poll last week in those communities “to get an understanding of the census and what that means for them.”

The organization will also pull together a larger messaging campaign, also targeted at particular communities, to urge people to fill out the census on their own, “because unless you can really spell out what the implications of an undercount means to folks, people aren’t excited about it,” Miller said. “No one wants to fill out a form...How can you make it sexy? How can you make it exciting so that people know that this is really critical to the health and the quality of life for all of us, especially New Yorkers?”

Miller noted that the implications of an undercount go beyond federal funding -- New York receives about $80 billion each year -- and a potential loss of representation in Congress.

“There’s voting rights and redistricting implications, there’s public and private research on social and economic issues, and something that folks don’t talk about that probably resonates with the private sector is that having reliable and good data dictates how businesses do business,” she said. “So as companies are doing their needs assessments and assessments of areas in which they might want to relocate or expand, they rely on data that talks about the population. Who lives there, what’s their education level. And then in terms of workforce. People love coming and operating in New York because of our talented and diverse workforce. And quite frankly, we’ve benefitted from programs that assist and support that workforce. And all of that is at stake when you undercount a population like New York.”

“There’s voting rights and redistricting implications, there’s public and private research on social and economic issues, and something that folks don’t talk about that probably resonates with the private sector is that having reliable and good data dictates how businesses do business,” she said. “So as companies are doing their needs assessments and assessments of areas in which they might want to relocate or expand, they rely on data that talks about the population. Who lives there, what’s their education level. And then in terms of workforce. People love coming and operating in New York because of our talented and diverse workforce. And quite frankly, we’ve benefitted from programs that assist and support that workforce. And all of that is at stake when you undercount a population like New York.”

Besides the decennial count, the Census Bureau also does the annual American Community Survey, which delves deeper into subsets of census data and then extrapolates that information to make assumptions about the larger population. “It really has a ripple effect,” said Romalewski of the CUNY Graduate Center, one of the area’s top census experts. “If the count is not done well in 2020, that will have an ongoing impact throughout the decade.”

He did note that there was at least one upside to all the challenges posed by the Trump administration, echoing what has been something of a theme on a variety of political and policy matters. “The silver lining in all of this is that there’s a concerted, coordinated effort early on to make sure people understand the importance of the census and that they participate fully,” he said.

The biggest “what if” factor in the entire census process is the legal battle over the inclusion of the citizenship question. The Justice Department is facing off in federal courts across the country against a broad array of plaintiffs including dozens of states and cities, including New York, immigrant advocacy groups, and the American Civil Liberties Union. Both sides issued closing arguments in late November in a trial in federal court in Manhattan -- other trials are on the horizon in other states -- and a judge is expected to issue a decision within weeks. The U.S. Supreme Court also agreed last month to hear arguments over whether Commerce Secretary Wilbur Ross can be deposed over how the decision to include the citizenship question was made.

“The thing I worry about the most is the fear tactics succeeding,” said Deputy Mayor Thompson. But he was undeterred even by the prospect that the highest court in the land could rule against the cities and states seeking to protect undocumented immigrants by ensuring they are counted. He likened it to the country’s history of racial segregation and slavery, which were held up for decades by courts and a Congress that maintained both were legal.

“So just having a Supreme Court go against you doesn’t mean you give up,” he said. “What changed segregation was actually when churches, ordinary Americans said enough is enough. And we have to have that attitude now. We’ll fight back...We have a history of fighting for our democracy. It wasn’t given to anybody, we got it through struggle and we might have to struggle again.”

This is part of AGENDA 2019, a joint Gotham Gazette-City Limits project

Find the rest of the series here

***

by Samar Khurshid, senior reporter, Gotham Gazette

@samarkhurshid @GothamGazette

WATCH: Agenda 2019: Movement Expected on Reform, But What Will It Look Like?

(photo: @MNN59)

This is part of AGENDA 2019, a joint Gotham Gazette-City Limits project

Find the rest of the series here

As part of Agenda 2019, the project from Gotham Gazette and City Limits, hosts Ben Max and Jarrett Murphy were joined on Manhattan Neighborhood Network by State Senator Liz Krueger, a Manhattan Democrat, and Susan Lerner, executive director of Common Cause NY, to discuss reform issues and the year ahead. Topics included voting and election reform, government ethics reform, and campaign finance reform. Krueger's new Democratic majority in the state Senate are pledging to work with the Democratic Assembly majority and Democratic Governor Andrew Cuomo to usher through a long list of stalled reforms, but what will actually get done? And what should it look like? Watch:

As part of Agenda 2019, the project from Gotham Gazette and City Limits, hosts Ben Max and Jarrett Murphy were joined on Manhattan Neighborhood Network by State Senator Liz Krueger, a Manhattan Democrat, and Susan Lerner, executive director of Common Cause NY, to discuss reform issues and the year ahead. Topics included voting and election reform, government ethics reform, and campaign finance reform. Krueger's new Democratic majority in the state Senate are pledging to work with the Democratic Assembly majority and Democratic Governor Andrew Cuomo to usher through a long list of stalled reforms, but what will actually get done? And what should it look like? Watch:

This is part of AGENDA 2019, a joint Gotham Gazette-City Limits project

Find the rest of the series here

***

by Ben Max, Gotham Gazette

@tweetBenMax @GothamGazette

Commission Recommends Pay Increases and Ethics Reforms for State Legislators

(Photo via Wiki Commons)

Statewide elected officials, legislators and agency heads are slated to get pay raises next year following recommendations issued Thursday by a four-member panel that was created in this year’s state budget.

The New York State Compensation Committee voted on Thursday to raise the salaries of legislators for the first time in nearly twenty years, as well as for the four statewide offices and for executive agency commissioners. The committee will publicly release a report and deliver it to Governor Andrew Cuomo and the State Legislature on Monday outlining their binding recommendations on phasing in the salary increases over three years, accompanied by certain ethics reform measures. The raises will go into effect by January 1 unless the state legislature meets and rejects them.

The committee -- which included State Comptroller Tom DiNapoli, New York City Comptroller Scott Stringer, former State Comptroller and SUNY Board Chair Carl McCall, and former New York City Comptroller and CUNY Board Chair Bill Thompson -- was created in the state budget to determine an appropriate raise for legislators, based on cost of living and on salaries for legislators in other states. The current base pay for state legislators stands at $79,500 and has remained unchanged since 1999.

Per the panel’s unanimous recommendations, salaries for legislators will be raised to $130,000 by 2021, with lawmakers set to receive $110,000 in 2019 and $120,000 in 2020. The commission also recommended limiting outside income for legislators to 15 percent of their salary, in line with the rules for members of Congress, and the elimination of committee stipends -- commonly referred to as lulus -- for all but the top leadership in both legislative chambers.

“I think in looking at the fact that they haven’t had a raise in twenty years...when you talk about the issues of fairness, it is not the right thing,” Thompson said, arguing that the idea that legislators only work part-time is a mischaracterization due to their in-district work. The limits on outside income will take effect in 2020, because, according to McCall, legislators would need time to disengage from their outside income-generating activities and could not do so right away.

The panel also endorsed raising the governor’s salary to $250,000 by 2021, up from the current $179,000. The lieutenant governor, attorney general, and state comptroller, each of whom currently make $151,000, will see their pay rise to $210,000 salary by 2021. DiNapoli recused himself from that vote.

The pay raise committee was originally meant to be chaired by Chief Judge Janet DiFiore, but DiFiore announced in May that she would not serve because she believed a judge determining legislative pay was unconstitutional. The broader constitutionality of the committee has also been challenged, as it is still unclear whether a pay raise can be authorized by outside officials or if it must be approved by the legislature. The panel members, however, insisted that their recommendations are enforceable for all their proposals except the raises for the governor and lieutenant governor, which must be approved by a joint resolution of the legislature. They also maintained that tying the raises to an outside income limitation and curbing committee stipends was within their authority, which could potentially invite legal challenges going forward.

When the salary raises are fully implemented by 2021, New York will surpass California and have the highest-paid governor and legislature in the nation. McCall noted that coupling the pay increase with outside income limitations would also quell the discontent New Yorkers feel about giving raises to a legislature that has long been marred by scandal and corruption. “We really have to make sure that we send the signals to the public about how serious they are about doing their job and doing it well,” McCall said.

For executive agency heads, the panel proposed four classes of salary, a decrease from the current six, which will be assigned depending on the agency. By 2021, commissioners in the top class will make $220,000 and commissioners in the bottom class will make $170,000.

Legislative leaders have expressed support for the panel’s recommendations. Senate Majority Leader Andrea Stewart-Cousins announced her support for the measure on Thursday, hours before the meeting, while also concurrently declaring support for ethics reform. Assembly Speaker Carl Heastie testified to the Commission last week in favor of the raise, noting that legislators have financial strains similar to their constituents. “They too must finance college loans, meet the cost of child care, and provide for the wellbeing of elderly parents and loved ones at home,” Heastie said. He further argued that, because so many legislators live in the expensive New York City metro area, a pay raise was warranted to more adequately reflect the high cost of living here.

The New York Public Interest Research Group, which advocates for government reform, was skeptical of the panel’s recommendations, pushing for a more comprehensive set of “corruption-busting” reforms. “While we agree that the Congressional model is appropriate to regulate legislators’ outside income, advancing a reform in this area alone is inadequate,” said NYPIRG’s Blair Horner, in a statement. “We note that the ethical problems that have plagued the state have not been limited to the legislative branch. Given the stunning pay-to-play scandals that have rocked government, reforms in that area must be addressed. Failure to do so highlights the inadequacy of the reform package.”

***

by Ben Brachfeld, Gotham Gazette

@GothamGazette

Panel Previews 2019 Rent Regulation Discussion in Albany

(photo: Edwin J. Torres/Mayoral Photography Office)

This is part of AGENDA 2019, a joint Gotham Gazette-City Limits project

Find the rest of the series here

One of the most contentious issues on the 2019 docket in Albany will be the expiring rent regulations that apply to roughly 1 million apartments in New York City and determine several ways in which rents are capped and when and by how much landlords are allowed to increase rents or remove a unit from the regulated rolls. While the regulations are set to expire in June, it is widely expected that they will be extended, the main question is what exactly they will look like, and whether the fact that Democrats are set to control both the governor’s office and both chambers of the state Legislature will mean sweeping changes that benefit tenants.

Though that debate is certain to heat up when Governor Andrew Cuomo gives his State of the State address and the legislative session begins in the new year, a lot of discussion is already happening. On Tuesday, the New York Housing Conference hosted a panel discussion with key stakeholders in the rent regulations debate: State Senator Liz Krueger, a Manhattan Democrat; Assemblymember Steven Cymbrowitz, a Brooklyn Democrat; John Banks, the president of the Real Estate Board of New York; and Thomas McMahon, principal of consultancy TLM Associates. The hour-long discussion, which largely focused on rent regulations, but also touched more generally on housing development, was moderated by Gotham Gazette’s Ben Max.

“The Senate Democrats will be heavily focused on ensuring an improvement and strengthening of tenant protections in our rent regulation system,” Krueger said at the event, signaling that her new majority conference is looking forward to working with an Assembly majority that has held rent regulations as a top priority for many years.

Housing was one of the most prominent issues of the recent elections in New York, with the broad and ever-present issue of affordability talked about all over the state, some state Senate candidates in New York City running campaigns largely focused on rent regulations, and public housing crises popping up throughout. A slate of progressive Democratic reformers were swept into the state Senate on the promise of, among other things, reforming rent laws such as vacancy decontrol and how major capital improvements are assessed, and many candidates rejected campaign contributions from real estate developers. Those Democrats now join other state senators who will take over the majority from Republicans who were especially close with large real estate interests, and plan to team with Assembly Democrats who have been looking to strengthen rent regulations on behalf of tenants for years.

As legislators, negotiating with the governor, look to reform rent regulations and get the new formula right, there are certain to be complicated discussions, as members of Tuesday’s panel made clear. Stakeholders, from activists to developers, tenants to landlords, legislators to bureaucrats, will want their say in how new laws will be shaped. The state’s rent regulation laws are set to expire in June, two months after the state budget is due. Working rent reforms into the budget would provide faster resolution and may offer an opportunity for broader horse-trading as often happens in Albany, but a rushed job could also potentially leave open loopholes or fail to adequately address the issue.

To the potential chagrin of some, the panelists advocated a slow and steady process instead of immediate legislative reform, while hitting on a variety of specifics that must be considered.

“We will move slowly,” said Cymbrowitz, the Assembly housing committee chair, after Banks, the head of the city’s most powerful real estate lobby, advocated the same. “We will not just throw legislation, take them out of committee and just put them on the floor. We will have discussions with our partners, we will talk about it, and if there has to be changes to existing legislation, we’ll look at that as well.”

The Assembly has passed rent reforms such as repeal of vacancy decontrol, which allows apartments to be removed from rent regulation, on several occasions, but the Senate has been opposed. Krueger said that while the new majority with many new members that she will be a part of has not held a conference she believes the Senate Democrats will be “very open” to repealing vacancy decontrol. Governor Cuomo, who has close ties to real estate, recently said on WNYC radio that if a vacancy decontrol repeal bill passed the Legislature, he would sign it into law.

Vacancy decontrol, vacancy bonuses, preferential rent, the Urstadt Law preventing New York City from controlling its own rent laws, and the way landlords can account for major capital improvements (MCIs) are just some of the policies that could be on the table in 2019. Advocates who want to do away with or drastically modify vacancy bonuses, vacancy decontrol, and how MCIs can be passed on to tenants argue that they will protect tenants in rent regulated apartments from abusive practices by landlords and will protect the city’s rent regulated housing stock, which has diminished significantly in recent decades.

After Senator Krueger said that her conference will be focused on strengthening tenant protections, she later added that vacancy decontrol would definitely be taken up, and singled out MCIs in particular as well.

“People are not saying end MCIs, we’re saying end the ridiculous system where if you put in for an MCI, you get to get paid back for it forever by adding it onto the rents and inflation-adjusting it forever, when on average you’re getting your full money back in seven years,” Krueger said.

For Banks, whose organization is made up of and lobbies on behalf of the city’s largest real estate developers and landlords, reforms pose a fundamental threat to the industry’s ability to do business, and to the availability of good and abundant housing in the city. He argued that vacancy decontrol, wherein an apartment leaves regulation after rent passes a certain threshold, is a tool to subsidize regulated units.

“At a fundamental level, rent regulations affect the amount of money that can go into a building, the revenue streams that go into supporting a building,” Banks said. “If those numbers are not sufficient to support the construction and maintenance of the building, then it will further chill production. It will limit people’s incentive to create additional supply.”

“We shouldn’t vilify the entirety of a segment of our economy that is as important to New York City and New York State as the real estate industry is,” he said.

Banks, as well as the other panelists, also singled out the city’s property tax system as a culprit in the increasing unaffordability of housing. A commission jointly empaneled by the mayor and City Council is currently working to discuss potential reforms to the property tax system, and City Comptroller Scott Stringer introduced a housing proposal last week to fundamentally alter the city’s real estate tax scheme. Whatever the city commission puts forth will have to then be dealt with in Albany -- like with rent regulations, the city has limited powers over its own affairs with regard to taxes, though property taxes are one area the city has significant leeway.

“It is so complicated, it is so obtuse, and there are layers upon layers of abatements and other incentives to try to get to the fundamental problem, which is it doesn’t reflect the policy realities,” Banks said, also referring to the system as “broken” and specifically calling out Class 2 property taxes, the owners of which he characterized as shouldering the greatest tax burden.

McMahon, who worked in government for decades before moving to the private sector, argued that the property tax reform commission could be used as an opportunity to help vulnerable New Yorkers.

“Should we be looking at using property tax reform to supplement low-income tenants?” he asked. “I think it’s a conversation that could be had. So it’s important that the budget be cognizant of the need to extend this program.”

On the issue of public housing, both Krueger and Cymbrowitz lent their support to using Rental Assistance Demonstration, which Mayor de Blasio recently announced would be expanded to dozens of developments throughout the city and leverages both federal vouchers and private funding to allow private companies to manage NYCHA properties, providing additional sources of revenue for housing authority developments and key upgrades to the deteriorating housing stock.

“The RAD model seems to be working very effectively in other parts of the country and the state,” Krueger said. She clarified her remarks by noting that she is not in favor of privatization of NYCHA, which some say RAD effectively does, or at least is a gateway toward.

Krueger also didn’t outright dismiss the idea of building on unused NYCHA land, a controversial process known as “infill,” but argued that the balance of market-rate and affordable units needed to be carefully found, noting that she has a development in her district where a building is being built that will be 50 percent market rate and 50 percent affordable.

Cymbrowitz talked about using NYCHA land to build senior affordable housing, but acknowledged that more senior and other affordable housing means less revenue being brought in by infill for NYCHA’s tens of billions of dollars in needs.

But Krueger also cautioned about how infill developments are designed in terms of revenue.

“A real sticking point for the community was who’s getting the money that NYCHA will get from the building,” Krueger said. “Residents want their problems fixed, and many of their position is if you’re going to be putting a new building on our site, you’re taking away a playground, at least the money that’s coming in should come to meet the needs of this facility.”

This is part of AGENDA 2019, a joint Gotham Gazette-City Limits project

Find the rest of the series here

***

by Ben Brachfeld, Gotham Gazette

@GothamGazette

Agenda 2019: High Hopes for Long-Awaited Reforms

Gov. Cuomo signs legislation (photo: Kevin P. Coughlin/Governor's Office)

This is part of AGENDA 2019, a joint Gotham Gazette-City Limits project

Find the rest of the series here

The 2018 election cycle in New York laid bare the myriad failings of the state’s political system that advocates and reform-minded elected officials have long recognized. Several candidates, many in it for the first time, ran competitive races on the backs of small dollar donors while highlighting the lax campaign finance laws that allow wealthy interests to fund campaigns across the state. Corruption in government and ethics reforms were salient issues, particularly so in the gubernatorial and attorney general races. In New York City, chaotic Election Day administration brought renewed scrutiny to the long mismanaged Board of Elections as well as the state’s arcane voting and elections laws. And voters, for the first time in a long time, seemed to be paying attention to it all.

“There is a tremendous amount of demand for democracy reforms,” said Sarah Goff, associate director at Common Cause New York, a government reform advocacy group. “The state Legislature has the unique opportunity, with the dramatic shift in landscape, to prove to voters that they got the message.”