Council Approves Penn Plaza

Rendering from Pelli Clarke Pelli Architects

The Empire State Building better move over. It's about to share some skyline.

The City Council on Wednesday approved a controversial 67-floor skyscraper, reaching nearly 1,200 feet, just two blocks away from the Empire State Building. The Empire State Building is 34 feet taller than the proposed structure.

Opponents of the project, which include the Empire State Building's owners, said the new tower -- to be developed by Vornado Realty Trust -- would block the views of arguably New York City's most iconic structure.

In the end, Council Speaker Christine Quinn, who represents the area, said the new skyscraper embodies what New York is all about -- the constant need to grow and expand.

"New York City has never been a city that stays stagnant, that stays the same," said Quinn. "We want new Rockefeller Centers. … New York City is about growth -- about growing bigger and higher all the time."

Skyscraper Showdown

The council voted 47 to 1 to approve the tower, otherwise known as 15 Penn Plaza, with Councilmember Charles Barron dissenting.

Within the council the obstructed views did not cause as much concern as the initial lack of a commitment from the developer to contract with women and minority owned businesses. Yesterday, Quinn said she received a pledge from Vornado to set aside 15 percent of its contracts for them.

The commitment did not minimize all of the opposition among council members.

"This is a project for the rich, for the elites," Barron said. "When they say thousands of jobs, for who?"

The local community board also opposed the project, pointing out Vornado has no anchor tenant and no set construction date.

Quinn defended the developer, arguing no one goes through the land use process unless they intend to build.

In response to yesterday's vote, a spokesperson from Vornado released the following statement: "We wish to acknowledge the efforts of the City Council, the City Planning Commission, the borough president and all those connected with the approval of our project, which we believe will be an outstanding addition to New York's iconic skyline. We look forward to working with the Council to implement strong minority and women participation in the development and construction of 15 Penn Plaza."

The tower will include more than 2 million square feet of office space, 11,126 square feet of retail space and up to 100 underground parking spots. The developer has also committed to $150 million in transportation infrastructure improvements, including refurbishing the "Gimbels" underground walkway from Penn Station to Herald Square. These new pathways will connect Sixth and Eighth avenues.

Quinn said the project would create at least 6,000 construction jobs and add more than $3.3 billion to the city's "economic output."

While the development sparked public outcry to protect the Empire State Building's spot on the New York skyline, ultimately the prospect of thousands of jobs and the promised economic boost won out.

Anthony Malkin, president of Malkin Holdings, the owner of the Empire State Building, said in a prepared statement: "The City Council is the decision maker on this subject. They have gone out of their way to listen to our position. In the end, they are the elected representatives of the City of New York, and it was up to them to decide."

Mayor Michael Bloomberg too expressed support for the new tower. "Competition is a wonderful thing," he said early this week.

Protecting Tenants

In addition to the approval of 15 Penn Plaza, the council passed legislation (Intro 87) that would require more disclosure from landlords, making it easier for tenants to contact them.

Currently, owners of multi-dwelling residences are not required to list personal contact information in their annual report to the city. Much of the time, according to council officials, a landlord will list the name of a limited liability corporation or a management company instead of his or her personal information.

"Currently the situation is pretty much hide and seek," said Councilmember Melissa Mark-Viverito, the bill's main sponsor.

Under the bill, which was approved unanimously, any person who owns more than 25 percent of a multi-unit dwelling would have to list personal contact information.

Gay Marriage Out of State

Now that the State Senate has blocked the approval of same-sex marriage, Quinn, the City Council's first openly gay speaker, is making sure gay New Yorkers who want to tie the knot know where to go.

Under legislation (Intro 260) approved by a vote of 47 to1, the City Clerk's office will be required to post on its Web site and hand out at its office information on where gay New Yorkers can get married, including states and international destinations. It will also have to provide couples information on what rights they are entitled to here in the Empire State.

"I hope it's a message to the State Senate of how sick and tired we are of waiting for marriage equality," Quinn said.

The only member to vote against the bill was newly minted Councilmember David Greenfield of Brooklyn.

Currently, five states allow same-sex marriage: Connecticut, Iowa, Massachusetts, New Hampshire and Vermont.

Charting a Better Way for Planning and Community Boards

In 2005, then-Deputy Mayor Daniel Doctoroff and then-City Council Member John Liu reached agreement on the Flushing Commons project. But now, with the project still needing final approval from City Council, both men have moved on to other jobs leaving the validity of the agreement uncertain.

The Charter Review Commission appointed by Mayor Michael Bloomberg, though initially focused on term limits and non-partisan elections, recently invited comments about the city's Uniform Land Use Review Process, or ULURP. While it is unlikely that the commission will propose changes in this process in time for them to be placed on the November ballot, the many comments heard at a recent hearing and during the 10 public hearings already held suggest that there is a huge gap between the land use professionals, in both government and the private sector, who tend to be satisfied with the way things work and suggest only minor changes, and the community activists who see major problems with the role of community boards and community planning.

The Charter Commission will hold five more public hearings before the end of the summer and shortly after that is expected to make recommendations to be placed on the November ballot. Bloomberg could then decide to continue the work of the commission, appoint another commission or retire the body entirely.

The New York City Charter is basically the city's constitution and the legal framework for the way government is organized and functions. The land use process went into effect in 1977 after a charter revision and was most recently revised in 1989. Under the roughly seven-month review process, proposals for zoning changes, purchase and sale of city land and most major development projects go before affected community boards, borough presidents, the City Planning Commission and City Council where they are subject to public hearings and votes.

Preempting ULURP

Many key decisions about a plan, though, are made outside the ULURP process, leaving the formal seven-month period with theatrical posturing by proponents and opponents or just plain dull routine and numbing public relations performances.

The environmental review process mostly occurs before an application is certified as complete and ready for the land use review process. The environmental review is supposed to inform decision-makers about potential environmental impacts of a project or rezoning.

The reviews usually are done by companies that are hired by the applicant to protect the applicant from subsequent lawsuits. The experts are not required to make their findings understandable to the average citizen or elected official. As a result, the environmental reports are too long and complicated and not analyzed or interpreted in useful ways.

Much to the chagrin of developers, it can take months and even years of back-and-forth with city officials and experts to complete a draft environmental impact statement. With most changes to the environmental review made prior to the land use review process, elected officials and community representatives have a limited role in it. Community boards can review drafts of the environmental report, but they lack the professional expertise and staff to conduct any in-depth analysis.

Many applicants do not want to risk the cost and uncertainty that the land use process implies, so they meet informally with community representatives and public officials before the proceedings begin. They often negotiate concessions with interested community groups and adjust their proposals. While this may be an inevitable part of the political process, much of it happens behind closed doors, undermining the required public procedures. City officials may make promises of government expenditures and services, and private developers may agree to provide certain community benefits, all outside the public arena.

To those not involved in these discussions, the process has become a rubber-stamp for decisions that were already made. While minor changes are often made during the review process, very few rezonings or major development projects have been rejected or substantially altered during it.

In recent years, City Hall has taken to writing up extensive agreements with community representatives -- let's call them side agreements -- that set out in advance conditions for community approval of the proposed project or rezoning. These are negotiated before and during the land use review period. And the written agreements are not subject to oversight nor are they necessarily enforceable.

For example, a July 11, 2005 memorandum from then-Deputy Mayor Daniel Doctoroff to then-City Council Member John Liu committed to conditions for the Flushing Commons project in Queens. The project is currently at the final stage of review awaiting a City Council vote. Yet City Hall changed its mind about major details of the project after Doctoroff left government and John Liu left the City Council to run for comptroller. The validity of the agreement is uncertain.

Other agreements, such as one that went along with the rezoning of Williamsburg in Brooklyn or the deal drafted by then-Bronx Borough President Adolfo Carrion to help gain approval for the new Yankee Stadium, raise serious questions about legality and enforceability, as well as the issue of who truly represents the "community.". The flowering of such activity both before and outside the land use review process surely indicates that something is not working with that process. With that in mind, the time has come to look at measures that bring openness, transparency and enforceability to the land use process without making it any longer or more complicated than it has to be.

The Need for Planning

Some of these problems would be resolved with better and ongoing planning by the city and communities. During the land use process, communities often raise longstanding issues relating to services, especially transportation and schools. Neighborhoods experiencing new development spurred by rezoning, particularly in Manhattan and parts of Brooklyn and Queens, now find themselves with new traffic problems and even more overcrowded schools. If the city encouraged more long-term comprehensive planning, residents might have greater confidence that their concerns about key services would be addressed Instead, many communities fear that new development will only aggravate existing service shortfalls.

But New York City does little real planning . The Department of City Planning, the agency entrusted with planning in the charter, is fixated on ad hoc localized zoning instead of planning. Zoning regulates the built environment but doesn’t deal with most of the complex issues that New Yorkers care about. It regulates new development but does little to address most quality-of-life issues or solve serious problems in our neighborhoods. And there is an inherent conflict of interest with the city planning department charged with both pushing for zoning changes and with providing information and support to communities that might want to question those changes.

The City Charter mandates comprehensive planning documents such as the Strategic Plan and the City Planning Department's own strategic plan, but these are not subject to public review and approval and may not be regularly updated. They are virtually unknown documents that get filed away

The first major publicly disseminated comprehensive plan in decades was PlaNYC2030, issued in 2007. But the administration did not submit the plan for debate and approval to the community boards, borough presidents, City Planning Commission and City Council in accordance with Section 197-a of the City Charter. While the plan includes many good projects, it has major gaps, does not recognize a role for neighborhoods, and remains a strictly executive document that may have a life limited by the tenure of the mayor if the next mayor decides not to fund the plan.

While citywide planning occurs in New York, it is piecemeal and not connected to community-based planning. Since the 1989 Charter revision gave community boards explicit authority to introduce their own local comprehensive plans, almost a dozen 197-a plans have been approved. But at this rate it will take a century before every community board has an approved plan.

The community planning process is lengthy and burdensome, and the City Planning Commission can hold it up indefinitely. Community boards lack resources for planning, and nobody in government has the responsibility for getting the plans implemented.

In some cases, such as Williamsburg, the city's rezonings have undermined previously approved community plans. This has discouraged many communities from planning in the first place, and those that do steer away from seeking official approval. Of some 100 community plans, only a fraction was submitted for official review. City planning has determined that the plans are "advisory," which in practice sends the message that they can be ignored with impunity.

Community Boards

The city's 59 community boards are where the ULURP process is closest to the ground, where decisions about land use have a direct impact on the places people live and work. But community boards also lack the staff and resources to fully engage in the process in a meaningful way. The average board has a budget under $200,000 a year (and shrinking) to cover an area with more people than most municipalities in New York State have. Together the boards get less than .02 percent of the city budget.

Without resources, community boards cannot afford to get independent professional advice to evaluate the complex land use issues before them. Board members are volunteers and get no systematic training. Oversight of community boards is limited, and shortcomings can become systemic and longstanding. Too often community board members, appointed by their borough presidents, do not reflect the diversity in their communities, reducing their legitimacy.

Community boards in wealthier areas of the city may compensate by mustering their own free or low-cost experts. They may enjoy privileged access to decision-makers and feel little need for a change.

These communities, though, may not have the greatest stake in changes in community boards and their role in the land use review process. Other areas face substantial life and death issues centering around land use, such as environmental hazards resulting from waste facilities and transportation infrastructure or displacement pressure resulting from rapid development. These areas are disproportionately low-income communities of color. It is no coincidence that these neighborhoods have done a large number of community-based plans in the city and often seek to boost the role of community boards.

The public discussions about the City Charter offer an opportunity to rethink the way the city does land use review and planning, and fill the gaps left open because community boards don’t have a level playing field. We shouldn’t let backroom dealing trump the Uniform Land Use Review process, let zoning trump planning, or let community boards down.

Tom Angotti is Professor of Urban Affairs and Planning at Hunter College, City University of NY, editor of Progressive Planning Magazine, and a member of the Task Force on Community-based Planning.

High Speed Internet Access Opens Another Digital Divide

Photo by KOMUNews

High-speed modems, such as these allow speedy access to the Internet, something many New York households lack.

In New York City, a whopping 98 percent of residents have cable service available to them. Yet only about 46 percent of the city's households subscribe to the broadband Internet that cable can provide.

The cost of being hooked up to broadband simply is too high for many low-income New York residents. A 2006 American Community Survey indicated that in New York City, a mere 26 percent of low-income households had the high speed service at home, compared to the 54 percent of moderate-to-high income households -- indication of a very clear "digital divide."

Advocates in New York City believe that the below average rate of wired and wireless broadband Internet deprives people in low-income communities of educational and work opportunities, since such access quickly is becoming one of the greatest economic equalizers.

The high-speed Internet provided by the increased bandwidth allows customers to upload and download data more than 10 times faster than they can on dial-up service. A small business that operates a website for its customers would therefore be much more productive and more competitive if it had access to broadband.

Civil rights groups, such as Journalists of Color and National Hispanic Media Coalition, as well as academics, have urged the government to launch efforts to promote the use of broadband, in immigrant, minority and other low-income communities. In response, New York City, with help from federal money and nonprofit organizations, has begun to implement policies in the hopes of creating equal opportunity to access the Internet.

Beyond Reach

In an early 2010 study done for the Federal Communications Commission, the Social Science Research Council found, "Broadband access is increasingly a requirement of socio-economic inclusion, not an outcome of it."

High speed internet access has rapidly become almost a necessity as people use it to run small businesses, interact with government agencies and do school work at all levels. Certain job applications, including those for entry-level positions at Target and Home Depot, are available exclusively online. While low-speed access is available, experts say it is so slow that it is practically worthless.

But the costs of high speed make it prohibitive for many New Yorkers. Dharma Dailey, a researcher who helped conduct the Social Science Research Council study, said the overall cost of having a broadband connection includes much more than just the monthly fees, which range from $20 introductory rates to over $70. People also must purchase a computer and modem, and pay fees for installation, repairs and virus protection, Providers often charge low-income consumers extra deposits and other fees.

Researchers made site visits to four states considered in the council study, including New York. They found disproportionately low broadband adoption rates among African Americans and Latinos, who make up a large portion of the city's population.

This has prompted many groups to call on governmental agencies to help promote access to broadband services among those with low incomes.

The Government Response

The passage of the American Recovery and Reinvestment Act of 2009 resulted in the appropriation of $7.2 billion in federal money to tackle the problem of getting broadband in underserved communities throughout the nation.

The Broadband Technology Opportunities Program was initiated to disburse funds to different states. As a result, Gov. David Paterson issued Executive Order 22 creating the New York Broadband Development and Deployment Council to devise a plan to spend its slice of the federal funds and work toward universal broadband adoption. A few months later, three New York City advocacy group leaders and others across the country wrote a letter to Federal Communication Commission chairman Julian Genachowski outlining the need for government programs to increase broadband adoption in underserved communities.

In the first round of federal funding, New York state benefited from five different telecommunications grants, some of which were targeted to rural upstate communities. The city's Department of Information and Telecommunications Technology, though, received $22.1 million, the largest grant awarded in the nation, for the NYC Connected Learning Program to focus on "sustainable broadband adoption" in New York City.

The project, which will aim to reach almost 20,000 low-income sixth graders attending 100 schools across the city, will provide broadband to the students but also will take a holistic approach to increase the broadband adoption rate. The program will provide the students with personal computers and discounted broadband Internet access. In addition, the program, according to Department of Information technology project manager Kate Hohman, will emphasize education to "build an appreciation of the value of broadband." To supplement the technology, the Connected Learning Program will offer basic technical training and online learning opportunities, along with bilingual assistance to avoid language barriers.

The program intends to benefit the students’ families as well. It is projected that over 14,000 households will subscribe to broadband as a result of NYC Connected Learning. City officials expect the program to be implemented in the fall.

For the second and final round of federal stimulus funding, the city has applied for two additional grants. Connected Communities would seek to enhance community computer centers in the most impoverished neighborhoods by alerting residents of their whereabouts, providing broadband access, and offering technical assistance and training. The city would create partnerships with community and senior centers, and set aside funds to increase computer access and digital literacy programs in public libraries. The city has asked for $15 million in stimulus money to pay for the program and will put up $9.7 million of its own funds.

The other initiative, NYC Connected Foundations, would allow high school students at 43 public high schools who are dropout risks to participate in a "Connected Foundations" that would emphasize digital literacy with the overarching goal of increasing broadband adoption in their communities. Students would also received computers and subsidized broadband access. The city has applied for almost $6 million from the federal government to supplement the $2.6 million that the city will provide.

Neither program has yet received approval from the federal government.

A Broadband 'Lifeline'

Another possible solution to low broadband adoption is currently being pursued as part of the National Broadband Plan, an effort to connect all Americans to high speed internet. As part of that, today from 10:30 a.m. to 12:30 p.m. the Federal Communications Commission will hold a roundtable discussion to explore broadband pilot programs for low-income consumers. (To view the discussion as it takes place or after the fact, go here.

The planned discussion is a result of the National Broadband Plan's recommendation to set up a broadband program similar to the current Lifeline/Link-Up programs that allow low-income customers to pay lower rates for setting up and maintaining secure telephone service. Under the program, all customers pay a small amount into the universal fund, which is used to bring fees down for those who either live in rural areas or who cannot otherwise afford to have service. Making Lifeline/Link-Up funds are available for broadband services as well, proponents say, could dramatically increase broadband usage for underserved parts of the population..

Depending on the results of today's discussion, the communications commission could launch pilot programs to see how best to operate the newly expanded Lifeline/Link-Up programs.

Beyond the Government

Not-for-profit groups in New York have also launched efforts to try to ensure digital equality for all city residents. In particular, People's Production House, a New York-based organization dedicated to bringing media democracy to underserved communities, has various programs to try to close the digital divide.

Its Digital Expansion Initiative focuses on educating youths, immigrants and low-income residents on matters related to technology. In addition to in-depth digital literacy and media studies training, the project seeks to inform individuals about government policies that affect online journalism and Internet access.

The group currently is seeking a grant of about $3 million from the second round of federal stimulus funding, in conjunction with the North Star Fund and 21 other organizations. The grant money, which would be more than matched by the North Star Fund, would pay for the New York Constellation of Community Computer Centers project. The money would allow the initiative, which already creates public computer centers, to expand and upgrade.

How 'Transit-Oriented Development' Will Put More New Yorkers in Cars

Queens West, like many of the large new developments in the city, will provide thousand of parking spaces when it is completed.

In its effort to achieve a "greener and greater New York" while accommodating one million new residents, Mayor Michael Bloomberg's PlaNYC2030 embraced transit-oriented development" -- the concentration of new housing in neighborhoods with good access to the city's subways and buses. The plan contends that such development will encourage these new New Yorkers to use mass transit rather than cars, helping to improve air quality and transportation efficiency.

In last year’s PlaNYC progress update, the mayor's office claimed "21 transit oriented rezonings" of neighborhoods such as the 125th St. Corridor in Harlem, Dutch Kills in Long Island City, St. George in Staten Island, and Coney Island as a major step towards sustainability.

The third anniversary of PlaNYC o Earth Day provides an opportunity to look beyond the rhetoric and examine the details of these supposedly sustainable rezonings. The unfortunate truth is that many of New York City’s "transit oriented" rezonings instead encourage automobile use by requiring off-street parking. They destroy the mixed-use, walk-to-work character of communities like Long Island City in favor of high-end residential redevelopment. At the same time, the city has missed huge opportunities to cluster new development around transit stations in outer borough neighborhoods like Bay Ridge and Corona, instead reducing development potential to preserve the car-oriented, suburban-like environment.

A California Concept

The term "transit oriented development" was introduced by Peter Calthorpe, a California planner and architect, in the late 1980s. Calthorpe defined it as a method to create dense, mixed-use, pedestrian-friendly, socio-economically diverse neighborhoods centered on transit stations. He believed that combining a rich local pedestrian environment with access to regional centers by transit would reduce dependence on the automobile and promote more environmentally friendly and sociable lifestyles.

With origins in the environmental, anti-suburban sprawl movement, transit oriented development was intended to be a more sustainable growth model for booming Sunbelt cities. Social equity was also a critical component, as this kind of development would provide a greater variety of housing types at a range of costs and allow access to jobs without the expense of owning and maintaining a car.

In the past decade, however, Calthorpe's term has increasingly been co-opted by the real estate industry to market any kind of moderately dense, urban infill development. If the concept of transit oriented development is diluted to simply mean density and proximity to transit without discouraging car use -- or encouraging socio-economic diversity -- then we miss Calthorpe's message entirely. And in New York City, where transit is just about everywhere, simply branding development "transit-oriented" can render the term meaningless.

Zoning for Drivers

Perhaps the greatest contradiction comes in the city's attitude toward parking. In striking contrast to the stated objective of PlaNYC2030 to reduce the number of cars on the road, the Department of City Planning continues to require most new developments to provide off-street parking - usually garages -- for residents.. In the past two years, studies by the Furman Center and Transportation Alternatives have called attention to the impact this has had on development patterns in the city.

While new development in Manhattan below 96th Street generally is exempt from stringent parking requirements, new projects in Harlem and in the outer boroughs must provide off-street parking in ratios ranging from 0.4 to 2 spaces per unit. Developers can apply to the Department of City Planning for waivers for small or irregular lots but not for large sites like those on the East River waterfront where much of the growth is taking place.

New York City neighborhoods built before the advent of the car, like Park Slope and the West Village, have an average of less than 0.1 off-street parking spaces per home. The increased number of spaces in rezoned neighborhoods like Long Island City, Harlem, and Greenpoint-Williamsburg -- close to the Manhattan core and touted by the city as transit-oriented -- will likely add tens of thousands of new cars to the city.

The convenience provided by abundant and free off-street parking is a major incentive for people to use cars rather than transit. Transportation Alternatives' study estimates that residents of new development are 40 percent to 50 percent more likely to own cars than typical New Yorkers.

As a case in point, the recent rezoning of Dutch Kills -- specifically cited as a sustainable transit-oriented rezoning in 2009's PlaNYC update -- incorporates minimum parking requirements of half to two thirds of a parking space per apartment. To the west of Dutch Kills on the Long Island City waterfront, the Queens West and Hunters Point South mega-developments, also lauded in PlaNYC, will add more than 6,000 new parking spaces when completed.

The city's parking requirements essentially exclude the possibility of developing traditional, walkable urban environments, the kind of neighborhoods that Calthorpe envisioned in his concept of transit oriented development.

With thousands of new cars and drivers entering the city thanks to all this new parking, the impact of these supposedly transit-oriented, sustainable rezonings will be just the opposite of PlaNYC's goals -- a larger carbon footprint, increased dependence on fossil fuels, lower air quality, and increased congestion.

And Neglecting Straphangers

In addition to supporting new automobile use, the city has done nothing to increase the capacity of the transit lines serving these neighborhoods, leading to serious overcrowding at stations like the Bedford Avenue L subway stop in Williamsburg. The Metropolitan Transportation Authority's current budget will actually cut service to PlaNYC's "transit-oriented" growth zones. The G train, a crucial link in the transit system for Brooklyn and Queens, will now terminate in Long Island City instead of running to Forest Hills, and numerous bus routes in the area are also facing major service cuts.

PlaNYC originally proposed to use the proceeds from congestion pricing to fund mass transit improvements, but when the charge to drive in Manhattan did not pass the state legislature, the Bloomberg administration had no back-up plan. There is a desperate need to expand transit service in Long Island City and North Brooklyn to accommodate the growing population. In order to avoid a dangerous increase in congestion and pollution, the city must aggressively engage with the MTA and state officials to establish a reliable funding stream for transit.

The city administration also has done little to encourage New Yorkers in neighborhoods farther from Manhattan in the outer boroughs to reduce car use in favor of transit. A study on the impact of Bloombergs rezonings released by the Furman Center last month finds that 59 percent of the lots that have been downzoned by the city are within a half a mile of a transit stop. Rather than encourage mixed-use, car-free density around transit stops in neighborhoods served by transit, like Bay Ridge, Dyker Heights, and Corona, the city has bowed to exclusionary local politics by downzoning (zoning for less density) and thus protecting the car-oriented suburban-like environment.

Diversity and Character

Social and economic diversity are critical aspects of true transit-oriented development. Ironically, though, the dense residential development that PlaNYC has encouraged in Long Island City and Greenpoint-Williamsburg through rezonings and "green" mega-developments like Hunters Point South threatens to undermine economic and social diversity in these mixed-use neighborhoods instead of encouraging it.

The Greenpoint-Williamsburg and more recent Dutch Kills rezonings removed longstanding protections for industrial businesses, allowing residential development as-of-right (without planning approval) throughout the neighborhood. Although the rezoning is technically "mixed-use" because light industry can legally remain, even a thriving industrial business cannot afford to pay the high rents that residential and retail can. Industry is being gradually pushed out to make way for condominiums paired with parking, high-end retail and restaurants -- a more profitable mix for developers but a less sustainable and equitable mix for New York.

As Adam Friedman, former director of the New York Industrial Retention Network has said, "If the city is serious about its commitments to reducing its carbon footprint … then the city needs local manufacturers to create green products. … If the city is to cut the income disparity … it needs to create well-paying manufacturing jobs and offer affordable space for industrial entrepreneurs."

True transit-oriented rezonings for Long Island City and Greenpoint-Williamsburg would have helped to keep housing and jobs in the neighborhoods by protecting the industrial and artisan businesses that in the mid-1990s were providing over 60,000 well-paying middle class jobs, according to the Department of City Planning’s 1993 Citywide Industry Survey.

PlaNYC's "transit oriented" rezonings also have failed to adequately protect affordable housing. The affordable units created by the city's inclusionary zoning program (commonly known as the "80-20" because developers receive a subsidy for allocating 20 percent of units to affordable housing) are outweighed by the loss of previously existing affordable units as market rents rise and rent-regulated tenants are pushed out by aggressive new landlords.

While transit oriented development is supposed to encourage socially and economically diverse neighborhoods, the evidence from PlaNYC's rezonings suggests that they are actually achieving the opposite -- displacing industry, local retail, and low and middle-income tenants from neighborhoods with good access to transit.

Suburbs in the City

PlaNYC 2030 has lead to numerous laudable sustainability initiatives in energy efficiency, bicycle infrastructure and bus rapid transit among other areas. But a survey of the city's zoning practices show that the "transit oriented rezonings," proposed in PlaNYC2030 and repeatedly portrayed as a major step toward sustainability, have not accomplished what they purported to do.

Instead of discouraging car use and promoting a diversity of housing and job opportunities as well as pedestrian and transit access, the city's rezonings are destroying existing mixed-use neighborhoods in favor of dense, high-end residential development paired with parking and retail. Further out in the boroughs, car-dependent suburban neighborhoods are being downzoned and preserved rather than retrofitted for sustainable transit-oriented urbanism.

The rezonings are increasing New Yorkers' reliance on the automobile and displacing good jobs and affordable housing from neighborhoods with access to transit, The mayor’s office and Department of City Planning should answer for that record.

Brian Paul is a master of urban planning student at Hunter College and fellow at the Hunter College Center for Community Planning and Development.

Early Steps -- and Bumps -- on the Road to a Greener City Economy

In a nondescript basement office on Essex Street, sandwiched between a check-cashing place and a video store, three business partners nurture their fledgling solar panel company, poised hopefully on the cusp of opportunity.

Edward Yau, a civil engineer, and brothers Jack and Steve Shao, an economist and electrical engineer respectively, all in their 30s, created Tensor Energy Co. last summer. They plan to import Chinese-made solar panels to sell here, and also to provide technical and design support to homeowners and businesses looking to install the systems.

So far, business has been slow to start, but the partners have secured a few contracts for the spring -- a home in Brooklyn, another in Queens and two small commercial jobs. They see opportunity at "the intersection of government policy and public awareness," said Yau.

"2010 is an important year," he said. "We will have to kick start the business."

Much like this startup company, the Bloomberg administration's plan to create a green economy in New York based on jobs that directly improve the environment is gearing up as well. The administration said in October it that intends to double the city's green-sector jobs from 13,800 to 27,600 by 2018.

How successful the city will be or what specific jobs will materialize is difficult to pin down at this point. The city's Workforce Investment Board currently is evaluating how to track jobs created by the mayor's green economy plan, according to a spokesperson for the city Economic Development Corp.

Getting Off the Ground

In the absence of concrete numbers, Tokumbo Shobowale -- the former chief operating officer of the Economic Development Corp., who now works for Deputy Mayor for Economic Development Robert Lieber -- sees momentum.

"All the policy is there and we're now putting in place infrastructure to make it happen," Shobowale said during a recent interview. "We're not in fourth gear cruising down the highway yet, but we are moving out of first and picking up speed."

He pointed to two projects funded this year by the Economic Development Corp. -- one a pilot program in Hunters Point in the Bronx to see how wind turbines work in the city and another providing grants totaling $200,000 to five institutions that agreed to invest additional money in solar-thermal heating systems, including New York Hospital Queens in Flushing and the Julliard School at Lincoln Center.

The push for more sustainable technologies has "now expanded beyond just environmental folks thinking about it, but people see the economic benefits as well," Shobowale said. "There are jobs to be created and businesses to be created out of this."

The Economic Development Corp. and its renewable energy projects are just pieces of the city's larger, multi-pronged plan for a greener economy. In its vision presented to the public last October, the city called on 10 agencies and departments -- including parks, buildings, the City University of New York and the mayor’s office -- to take on specific tasks.

The theory is that multiple programs run by different departments -- from tax incentives to career training to building code changes -- will fit together like cogs in a piece of machinery that eventually will churn out jobs.

Harnessed in that effort could be landscapers contracted to plant saplings as part of the Million Trees NYC initiative, retrained Wall Street types trading carbon emission allowances, or electricians finding new work retrofitting apartment buildings to make them more energy efficient.

Take, for instance, the project in Hunts Point, which was awarded to Urban Green Energy, a New York City wind turbine company with factories in China.

Nick Blitterswyk, the company’s co-founder and CEO, sees great potential for wind power in New York City. In fact, he said the city’s rooftops served as inspiration when he and his partner formed the company, which does business around the world. He is grateful that the city is exploring wind as an energy source. However, he said the current project -- to measure wind speeds from a warehouse roof and then to install one test turbine in May -- is small in scale. The company is using existing staff and has not hired anyone as a result of the contract, he said. Larger contracts here have been slow to materialize.

"We haven’t had as much pick-up as we'd like," Blitterswyk said. "There have been a lot of businesses that don't want to be first. They want to see it done first by someone else."

Shobowale said the turbine pilot program is just a first step. It allows the city to study the potential of wind power and then set protocol so its use can be expanded. Before the city can move to large-scale use of alternative energy sources such as wind turbines, he said, building codes need to be adjusted.

Changing the Code

The administration recognizes the need to make code changes in order to facilitate the greening of the city. A year and a half ago, the city commissioned a task force, led by the non-profit Urban Green Council, to recommend changes to building, construction and energy regulations to help the city meet the administration's goal of reducing New York's carbon emissions by 30 percent by 2030.

The task force delivered its 600-page report to the mayor’s office and the office of Council Speaker Christine Quinn in February for their review and future action, said Russell Unger, executive director of the Urban Green Council. Several of the recommendations -- including one that suggests all new commercial tenant space over 10,000 square feet be metered for electricity -- were already included in the city's Greener, Greater Buildings Plan, which became law last December, he said.

One other piece of legislation stemming from the Green Council's report was adopted in March when the mayor signed into law a bill that creates an Interagency Green Team and Innovation Review Board whose mission will be to facilitate the use of new green technologies and construction techniques in the city.

The Green Council report's other recommendations range from requiring builders to insulate the exteriors of high-rise buildings to adding temperature controls individual apartments so residents no longer have to open windows in the winter to cool down overheated homes. "The vast majority of the proposed changes to the code would kick in when someone does construction or renovation," Unger said.

These code changes, if adopted, would lead to more jobs in the city, Unger said. He explained that as more people make energy-saving improvements to their buildings, the cost of materials will drop, leading even more people to take the same steps therefore driving the demand for more workers such as architects, engineers and heating and lighting specialists.

"If everyone is doing it, it is going to reduce the cost of materials therefore lowering the barrier to doing work," he said.

One setback in the mayor’s green economy plan came last December when the administration -- faced with intense opposition from building owners -- dropped a provision in the Greener, Greater Buildings legislation that would have required building owners to pay for capital improvements to increase energy efficiency.

Under the legislation that passed, larger buildings have to undergo energy audits but owners are not required to make improvements. As a result, a plan originally estimated to produce some 19,000 jobs would create far less than that by many estimates.

Finding the Buyers

The owners of Tensor, too, are anxious to see prices for green technology drop, especially in their area of solar PV panels. Even with federal, state and city tax incentives, Yau said homeowners still balk at the initial investment even if they will get most of it back through tax credits and abatements and savings on energy costs.

According to Yau, an average single-family home would need a four-kilowatt system, costing as much as $35,000. An immediate state rebate would cover $10,000, leaving the homeowners to make an investment of up to $25,000.

"There is a market," Yau said. "The people who are installing panels are more affluent and environmentally conscious. They have the cash but lot of people get sticker shock over the fact that they have to lay out $15,000 to $20,000."

To help overcome that, Yau said the administration could facilitate financing for homeowners who wanted to install alternative energy systems, and it could quickly institute those code changes.

"The city needs to make the lives of installers easier," he said. "This type of project is viewed like a home improvement. You need Building Department permits, and regulations are not necessarily geared to solar projects."

Yau thinks that he and his partner are on the right track in focusing their sights on the New York metropolitan area. With the West Coast way ahead in green energy, he sees a vacuum on the East Coast that needs filling, and any assistance from the city would be welcome.

"If there is a will, they can help make it happen," Yau said.

Vera Haller, the former editor-in-chief of amNew York and editor of NYNewsday.com, currently teaches journalism at Baruch College.

lawmakers seek to crack down on illegal hotels

A room in the so-called Candy Hostel, one of three apartment buildings now used a budget hotels.

The "Candy Hostel" on Manhattan's Upper West boasts of being New York City's "newest, sexiest, hippest and hottest boutique hostel." It offers amazingly cheap rates -- as low as $17 a night in a city where the average hotel charges $312 -- and only accepts payment in cash.

As alluring as that may be to tourists on a budget, the building, formally known as the Mount Royal, along with the nearby The Continental and Pennington are not as hospitable for long-time residents who call the single room occupancy buildings home.

"The city doesn�t protect us. What�s happening here is illegal," one man said. When asked to elaborate, he took a puff of his cigarette, then shook his head, and said that he could not comment any further because he was afraid of retaliation from his landlord.

For years, the owners of the three buildings -- ownership information remains murky as to who exactly they are -- have been renting out apartments to tourists, to make a greater profit than they can from the low-income tenants. The three, on 94th and 95th Streets, contain rent-stabilized apartments and are Single Room Occupancy buildings, or SROs where tenants typically share bathrooms and kitchens. The certificates of occupation for each building says that they are all Class A multiple dwellings, which means that they are classified as buildings for permanent residents.

Critics say that renting rooms out to tourists siphons away affordable housing for low-income New Yorkers. and the city regards such rentals as illegal. A recent statement by Mayor Michael Bloomberg said that such hotels "all too often create fire safety and security hazards and create quality of life concerns in residential neighborhood." This is because these residential buildings do not necessarily follow fire safety regulations that a legitimate hotel would have to follow.

The press release hailed bills in the state legislature that would help sharpen the definitions of transient and permanent occupancies, ambiguities that the building owners have taken advantage of to skirt the law. A bill also has been introduced in City Council.

Legal Standing

As of 2009, the number of such hotels in the city has 280 buildings, according to a report by the Illegal Hotels Working Group.

The law is sketchy regarding the definitions of transient and permanent occupancies. In 2007, the city obtained a preliminary injunction prohibiting the use of these three buildings as hotels. The city contended that short-term stays were illegal for buildings with Class A status and that stays of less than 30 days violated a zoning resolution that forbid "transient hotels" that were used "primarily for transient occupancy" from being located in a residential district.

But in 2009, a state appeals court decided that the building owners could continue renting units for short stays. Justice David Friedman ruled, "While the city's evidence demonstrates -- indeed defendants readily admit -- that a significant number of units in each building are (and have been for many decades) rented to tourists for periods of less than 30 days, the city made no showing that most of the units in any of the buildings are rented for such short-term occupancy."

An Economic Engine?

David Satnick of Loeb and Loeb LLP, who represented the Continental and the Pennington in the case said at the time that in light of the "current economic turmoil," owners of SRO hotels should be permitted to rent units to tourists because it , "generates tremendous income for the city by way of taxes." Scott E. Mullen, an attorney who represented The Mount Royal said the ruling was extremely important for the city's tourist industry.

Assemblymember Micah Kellner, who has supported legislation against such hotels does not agree. He has said, "Illegal hotels are terrible for New York City's reputation as a quality tourist destination."

Certainly, though, the hotels attract visitors. On a recent day a young Asian couple walked through the doorway of the Continental building toting a large purple suitcase. Brochures about visiting New York City tourist sites such as the Empire State Building, the Statue of Liberty and the Bodies Exhibition were displayed right upon entry. Inside the lobby, people surf the Internet on their laptops. Three tourists from Europe, two from England and one from Ireland said they decided to stay at the Continental because the rates were so low: $120 for seven nights.

"If there wasn't a place as cheap as this, we may not have come to New York City," said a British tourist staying at the Continental, who said that the accommodations were fine. Or, she added, "we would have had to save more money and come at a later time."

The tourists did not realize the building was primarily residential. The Irish visitor said that he noticed approximately 30 tourists checking in at the lobby the night before. "I can see how that must be so annoying for the residents," he said.

By most accounts, the accommodations are modest at best. In reviews of the Candy Hostel on tripadvisor.com, many tourists complained of unclean shared bathrooms, rooms with rat traps, doors with broken locks, infestation of bed bugs and issues with payments. The Continental, called The Fresh Hostel had similar negative reviews.

Insecurity at Home

The long-term tenants have different concerns. According to the Cooper Square Committee, tenants living in these buildings feel less safe as strangers o in and out of their buildings. Housing Conservation Coordinators charges that landlords who operate these hotels often harass legitimate tenants to force them to make more rooms available for tourists.

"All they have to do is force out permanent, rent-stabilized residents. They do this by making tenants' life miserable through systematic harassment -- lockouts, threats, frivolous lawsuits -- they're very effective. Ultimately, for every building where landlords can operate an illegal hotel with impunity, we can count on those affordable units disappearing," Matt Wade, a tenant organizer at Goddard-Riverside Community Center's West Side SRO Law Project has said.

"Illegal hotels are kicking out tenants and taking much-needed apartments off the housing market," John Raskin, the director of organizing at Housing Conservation Coordinators has said.

On a recent drizzly March day, several tenants seemed fearful, declining to give their names to a reporter. When security guards noticed that I was speaking to residents, they asked me to leave the premises for "soliciting," and ultimately called the police on the grounds I was "harassing residents." One security guard followed me for two blocks until I was met by police officers who questioned me briefly.

If the tenants do move from these buildings, many will find it difficult to get another place to live. Marti Weithman, project director for Goddard Riverside SRO Law Project has said that tenants forced out of SRO units are low-income New Yorkers who may turn up in the homeless system.

Looking to Legislation

In light of such concerns, Assemblymember Richard Gottfried has introduced a bill that would clarify provisions relating to occupancy of such buildings. It calls for defining the term "permanent residence purposes" as occupancy by a "natural person" or family for 30 consecutive days or longer. This clarification is intended to clear up the ambiguities in the law . Currently, building owners say that the permanent or long-term residence requirement is met when the unit is leased by a corporate entity for more than 30 days, though it may occupied by actual persons for less than 30 days.

State Sen. Liz Krueger has proposed similar legislation in the State Senate."

Current penalties for the operators of such hotels are $800, regardless of the number of units being converted, the length of time the unit was used as a hotel room, or whether it was a repeat offense. Intro 534, introduced by Councilmember Gale Brewer, would increase the penalties for such violations from $1,000 to $,5000 for a first offense, and introduce a per-unit, per-day fine structure.

"Permanent residents who have to get up in the morning for work, and tourists who are on a tight budget and partying while on vacation, are not compatible 'living' next door to each other, sharing the bathroom, or meeting in the hallways," Brewer has said.

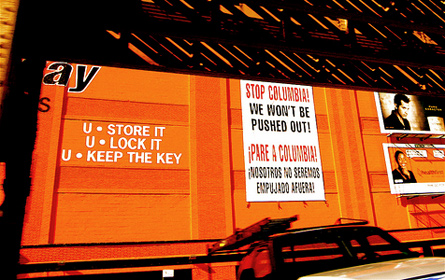

Eminent Domain Changes Seek to Limit State's Power to Seize Property

The owner of a storage facility near Columbia University has challenged the university's use of eminent domain to take his property.

When Henry Weinstein bought a commercial building at 752 Pacific St. in Brooklyn 1985 he never expected that 20 years later the government would want to take it away and give it to a developer. Weinstein said that he would be shocked if his land was being taken for a hospital, a bridge or a library. But seeing it seized to make way for Forest City Ratner's Atlantic Yards project shakes his faith in the government. "This is the most un-American thing I have ever experienced," he said.

As New York City has reshaped itself over the past decade, the government has given private developers, such as Forest City Ratner, a powerful tool -- an eminent domain law that allows them to seize land from other property owners. Now some politicians believe the law needs change to protect property owners, such as Weinstein.

Assemblyman Richard Brodsky has put together a package of legislation that would create a commission to review the state's eminent domain process, give land owners fair compensation for their property and establish an ombudsman who would help land owners whose property is targeted by eminent domain. Later this week Sen. Bill Perkins will unveil legislation that he says would change the state's eminent domain laws to better protect property owners. The situation in the legislature, along with a recent appellate court ruling that found the process the state used to take land for a Columbia University satellite campus in upper Manhattan was unconstitutional, could result in the first major changes to New York's eminent domain laws in more than 30 years.

The possibility that the state might finally redo its eminent domain laws -- laws that have remained the same as other states updated theirs -- has caught the interest of civil rights lawyers, property owners and advocates. But developers, real estate interests and some politicians fear changes could make it more difficult for the state to improve blighted neighborhoods in desperate need of investment, infrastructure and jobs.

"Eminent domain is an essential governmental tool that allows for the implementation of important development projects to the benefit of the public at large," Lisa Willner, public affairs manager for Empire State Development Corp., which oversees the state's eminent domain process, said in a statement.

As the legislature considers the law, Weinstein is fighting the taking of his land in court. He acknowledges his legal battle may be futile. "The Empire State Development Corp. rules as kings. We left England to get away from it, but they have the power of a sovereign," he said.

Defining Blight

The state can seize property it determines to be blighted. While the state generally heads up eminent domain projects, in some instances, such as the Atlantic Yards case, the developer's advocacy leads to the state's involvement.

State law defines blight as "substandard and insanitary." Land that is determined to be blighted can be given by the state to another private owner for the purpose of economic development. The state can also use blight determination to make way for public works projects such as roads.

According to attorney Michael Rikon, who represents property owners in the Willet's Point section of Queens, where the city is planning a major redevelopment, the term is so vague that the contractors used by the government basically make up formulas as they go along. "The definition of blight is so broad it could come down to cracks in the sidewalk. Even the mayor's townhouse could be blighted, because it only supports one family," he said.

Civil rights attorney Norman Siegel, who represents Tuck-It-Away, a storage company that is fighting Columbia University's expansion plans, agrees. "Basically they are saying if there is a Motel 8 and Hilton comes along and says they can make the property more valuable, then it [the Motel 8] can be declared blighted." Many advocates, Siegel said, have begun saying the land in these cases should not be labeled "blighted," but "coveted."

Siegel calls eminent domain one of the premier civil rights issues of this century. "I really think it is the civil rights issue of the 21st century. It disproportionately impacts poor neighborhoods and people of color. It cuts across partisan lines," he said.

The Eyes of the Beholder

Of further concern to Rikon, Siegel and others is who makes the call. While the board of the Empire State Development Corp. technically determines whether a property is blighted, the agency hires a contractor who is paid millions of dollars to conduct the technical study and write a report. In the case of Columbia's campus expansion, the university and the development corporation used the same contractor, AKRF, at the same time. In the case of Atlantic Yards, AKRF worked for the developer, Forrest City Ratner, and then for the ESDC.

In his ruling against Columbia, Justice James Catterson described AKRF's study of land for the Columbia University project as "idiocy." Saying that the report cites such easily reparable problems as "unpainted block walls" and "loose awning supports" as blight, Catterson wrote in his majority decision, "We questioned [AKRF's] ability to provide 'objective advice' to the ESDC, particularly with respect to its preparation of the blight study."

Advocates say that the ESDC does not have to use AKRF as there are other qualified firms that do the same work. "Our judgment is that AKRF is the most qualified to do this work," a spokesperson for the ESDC told the New York Times.

For the Empire State Development Corp. to use evidence supplied by someone working for the contractor "seems like collusion. It doesn't seem fair, and sometimes perception is more important than fact. The entire process seems blighted," said Perkins.

AKRF defended its conduct. "As a firm of planners and analysts, AKRF's responsibility is the collection and assessment of data in an objective and thorough manner," a spokesman for the firm said. '"Any suggestion that the firm -- widely recognized as a trusted industry leader -- would compromise the quality of its work is incorrect."

"We need a more discrete definition of what is blight, not paid consultants who decide for themselves," said Michael Rikon, the Willet’s Point attorney. Rikon said landowners who have been through the process tell him. 'On the form for blight that consultants use there is one box for blighted and they check it.'" The process is much more complicated than checking a box. But critics say the formulas used almost always lead to the same conclusion -- and it's one that favors developers.

Changing the Process

According to Siegel, property owners only get one, very narrow chance to argue that their property should not be taken away from them. He said landowners in other states have more of an opportunity to challenge decisions. "As far as I can tell New York is the only state where you start at the appeals level," Siegel said. "You get 15 minutes to argue. There is no cross-examination. I think it is a violation of due process."

Perkins and Brodsky hope to address that issue in their legislation.

Brodsky has been working to change the eminent domain law for 10 years. "I don't think eminent domain should be stopped as a useful tool for the public good but with this pattern of private to private transfers I think the current laws may be inadequate. We need schools hospitals and libraries, but person-to-person transfer is an entirely different animal," he said.

One of Brodsky's bills would establish an eminent domain ombudsman "so that normal citizens are not overwhelmed." Brodsky also would like to see owners who lose their land in the eminent domain process be compensated 150 percent of the value of their property. "Anyone forced to hand over their property should share in the profits," said Brodsky. And Brodsky would create a process to review developer's plans to make sure the surrounding community would benefit. He also would create commission to review the scope and effectiveness of current laws, and would like to get rid of the finding of blight all together.

Perkins' bill is said to contain a provision that would change the definition of blight from substandard and insanitary to something more measureable, though what the new standard would be is not yet clear. The senator also would like to include a mechanism to ensure that developers follow up on their promise to the community and to review exactly what benefits the community can expect to enjoy from any project benefited by eminent domain.

The bill contains other tweaks, not yet announced, as well. Perkins says he expects bipartisan support in the Senate as well as help from the Assembly.

Amy Lavine, a staff attorney at the Albany Law School’s Government Law Center who helped Perkins put together his legislation, said it is not intended to disrupt the eminent domain process. "The definition of blight as it stands is very vague. We want to change that. The law increases transparency and accountability in the process. We are not interested in disrupting the process. We just want to make it better." Lavine said.

Thwarted Efforts

Change for New York's eminent domain process has been a long time coming. Over the years, legislators from both parties and both houses have tried in vain to make changes to the law to better protect private property owners only to find their efforts blocked by real estate interests.

In 1974, Rikon took part in a committee charged with making changes to the eminent domain process. "The last time New York changed the law was '77," said Rikon. "What happened was, when we got to the final version the city's lawyers and city corporation counsel eliminated a lot of provisions that they were against. That was 33 years ago. We really need to revise everything step by step."

Most states changed the process and the standards for applying eminent domain following a Supreme Court ruling in 2005. In Kelo v. City of New London [Connecticut], the court decided that a state can take property from a private owner and transfer it to another owner for the sake of economic development. Forty-three states then changed their laws to protect property owners. New York did not.

"Kelo caused a firestorm around eminent domain because people thought eminent domain could only be used for government projects. Kelo said that's not true. It can now be used for public betterment," said Siegel.

In 2009, four years after the monumental Kelo decision, the case was in the news again. The developer that was the beneficiary of the Supreme Court's decision pulled outof the city, and now New London has been left with barren lots.

After 30 years, some observers think Perkins will be able to seize upon public sentiment in an election year and force drastic changes in the law. Brodsky said it would be about time. ""I have been at this for 10 years. I did not jump in after Kelo. It would have been a good time to do this three years ago," he said.

"It could become a firestorm if Bill pushes the issue and more people join in. Folks are angry at politicians. This will be a ripe issue. I think Perkins is sensing that. I know it is certainty ripe with us and with our clients," said Siegel.

On the other side, the real estate industry and other businesses will likely work to preserve much of the state's eminent domain law. They proved this in 2005 in the wake of the Supreme Court's Kelo decision.

"We are alarmed," Kathryn Wylde, president of Partnership for New York, told the state Assembly in 2005, when legislation to alter eminent domain law was being considered. "Without the power to condemn private sites to support economic development projects, New York and other older urban centers could not have kept pace with demands for upgraded infrastructure, modern office facilities and an expanded housing stock."

Serious opposition to changing the process could very well come from Mayor Michael Bloomberg. Advocates say the mayor's office has lobbied hard against such changes in the past. Recently in a New York Times article on the subject of eminent domain reform, Lisa Bova-Hiatt, a deputy chief at the New York City Law Department, said the city would not be opposed to "thoughtful change" but would oppose "ill considered action" sparked by hysteria.

Perkins right now is taking that as a good sign. "We welcome the mayor's help," he said, "I think it would be very valuable."

The governor could represent another obstacle. Following the decision by the appellate court that halted the Columbia expansion, Perkins called on Gov. David Paterson not to appeal the decision. He also asked the governor to institute a moratorium on eminent domain. "I remember standing with the Senate minority leader, now Gov. David Paterson, on the steps of city hall when the Kelo decision was announced. David was very concerned about the use of eminent domain back then," said Perkins.

Five years later, Paterson declined to heed Perkins' request, but Perkins hopes Paterson might still be convinced to join his cause.

Whatever the governor does, Perkins said he thinks the public is on his side. "I'm optimistic the public at this time is calling for reform. They want more reform," he said.

In Kingsbridge: Will Derailing a Bad Project Lead to a Good One?

Photo (cc) http://www.flickr.com/photos/atomische/

If you only caught the last act of the show, it would be easy to attribute the City Council’s unprecedented 45-1 rejection of the Related Companies' "Shops at the Armory" to a unique alignment of the political planets. A third-term mayor, seemingly vulnerable after an unexpectedly close re-election; a City Council -- and its speaker -- eager to flex their muscles; and a Bronx borough president whose leadership star is on the rise.

But it took years of dogged community organizing and shrewd coalition-building around a clear vision for the city’s largest armory to position the Kingsbridge Armory Redevelopment Alliance, or KARA, to take advantage of timing, luck and maybe begin re-writing the rules on how major development projects get done.

Having accomplished the unthinkable and by defeating a project backed by the administration, KARA and its allies are gearing up to re-imagine a future for the armory that puts community needs first, doesn’t strangle the neighborhood in traffic and delivers jobs capable of lifting Bronx residents out of poverty.

(The debte over the armory project has renewed the fight over the "living wage" in New York City. For more on the issue and whre ti stand in City Council, see The Living Wage After Kingsbirdge. And to find out where your coucil member stads, go here.)

'We Drove the Process'

In the usual New York scenario, developers tee up their projects, and work quietly with city agencies to line up financing and approvals, as they court political supporters. The New York City Charter-mandated Uniform Land Use Review Process, known as ULURP, requires that major development projects, zoning changes and transfers of city-owned property be reviewed by the affected community boards, the borough president, the City Planning Commission and the City Council. It sets deadlines for each step that create a six-month window for public review. Only the City Council vote and subsequent action by the mayor are binding.

Communities are typically caught flat-footed when the ULURP clock starts ticking: It’s hard to assess the situation, coalesce around a response and put a strategy in play before the 185-day timer runs down. Instead, changes needed for the project to gain final approval from the City Council are often embodied in 11-th hour side agreements, negotiated behind closed doors.

In the case of Kingsbridge, though, Pilgrim-Hunter recounts a 13-year campaign, spanning two administrations, that began when the community and clergy coalition demanded that the armory be redeveloped, and reached a clear and early consensus that redevelopment had to meet community needs.

"If we had a singular advantage, it was that we initiated the process, and we drove the process through to the end,” said Desiree Pilgrim-Hunter, a leader of KARA and the Northwest Bronx Community and Clergy Coalition.

Their 1995 plan was anchored by schools -- members put the Bronx’s most overcrowded school district together with the city’s largest vacant building and reached the obvious conclusion.

Kwasi Akyeampong, also a community resident and KARA member, recalls, "We had a vision of how the armory should be developed to benefit the community. We were steadfast; we held our elected officials accountable."

The coalition kept the armory high on its agenda, and held rallies, marches and press conferences to ensure that elected officials kept it on theirs as well. The activists pushed for the transfer of the armory’s ownership from the state to the city (1996) and forced the city to spend $30 million to restore the building's 260,000 square foot roof and stabilize its landmarked exterior (2000). They dragged a succession of school chancellors through the building and through the coalition's own research on non-city sources of school funding. Finally, they waited out the slow death of a sole-source agreement between the Giuliani administration and Basketball City (1999-2002) that would have turned the armory into a commercial sports complex.

In 2003, the Northwest Bronx Coalition presented the more market-savvy Team Bloomberg with a mixed-use proposal of its own that would have divided the massive space between schools, recreational space and retail. The coalition navigated the Bronx's challenging political terrain to bring the Department of Education, City Council and Assembly members, then-Borough President Adolfo CarriĂłn and the city’s Economic Development Corp. together on an agreement to put out a request for proposals from developers. In 2005, the Economic Development Corp. announced the formation of a task force, which it pledged to "consult" as it drafted the request for proposals. Community members were heartened, but wary.

Meanwhile, not far away, the same city and state officials were on a very different track as they moved Yankee Stadium through the environmental impact statement and land use processes at warp speed, rolling over near-unanimous community opposition. And a few blocks farther south, the Related Companies were negotiating with Economic Development Corp. to build a shopping mall on the old Bronx Terminal Market site. On the day of that council vote Related's attorneys e-mailed a "Community Benefits Agreement" to community representatives. It provides few real benefit and so far the record on actual delivery of the promised benefits has been sketchy.

Labor Gets on Board

Community Benefits Agreements in Los Angeles and elsewhere have been successful. In New York, though, developers routinely use such agreements as cover for bad projects. In 2005, mindful of both scenarios -- and knowing that securing a seat at the table provided no assurance that the community would be served anything but crumbs -- 19 organizations founded KARA. They included the Northwest Bronx Community and Clergy Coalition, local housing and community organizations, and, in a departure from the standard community-vs.-developer playbook, labor with Service Employees International Union Local 32BJ, which represents porters, doormen and other property service workers; the NYC Building Trades; and the Retail, Wholesale and Department Store Union.

KARA’s platform demanded that the armory’s redevelopment prioritize uses that would serve the community, including schools. It also called for union construction jobs with local hiring and apprenticeships, and insisted that permanent retail jobs in the completed project pay a living wage – defined by KARA as $10 per hour plus benefits.

KARA hoped that employees of the armory’s tenants would end up carrying union cards. Like other industries, retail has seen the unionized share of its workforce shrink dramatically since the mid-20th century. Most retailers today pay poverty wages; they often employ immigrants who are most vulnerable to exploitation.

For its part, the retail workers union had worked with community organizations before, joining with Make the Road by Walking in Bushwick and working with GOLES (Good Old Lower Eastside) to create the Retail Action Project in SoHo in support of workers fighting against wage theft and other abuses.

Before the decline of organized labor in the U.S., unions were a part of the social fabric. If unions are to grow -- or even survive -- in the new economy, they need to rebuild their links to communities, according to Jeff Eichler, the retail workers' representative to KARA. Forming alliances and supporting low-wage, non-unionized workers in communities like the Northwest Bronx are very much in the unions’ self-interest, Eichler said.

KARA forged an alliance that could level the playing field with Related -- even when it became clear that city government, which should have been wearing referee’s stripes, was unapologetically playing for the developer’s team. As City Environmental Quality Review and ULURP mandated reviews rolled on, KARA examined reams of documents, bringing in experts in planning, finance, and traffic. "We did our research and kept the politicians up to speed," said Ava Farkas, lead organizer for the armory campaign since 2005.

KARA invited elected officials to reaffirm their support for the alliance and its principles. More than 1,000 community members turned out at an October 2009 meeting to hear Borough President RubĂ©n DĂaz Jr. call the fight for living wages in the armory a battle in "our new civil rights movement." Six weeks earlier, DĂaz had gone off the standard ULURP script and sent a negative recommendation to the City Planning Commission, citing the armory project's devastating traffic impacts and effects on existing local retailers. He also criticized Related's refusal to commit to a living wage requirement or negotiate a binding community benefits agreement with KARA.

City Planning approved the project, despite its seeming deviation from PlaNYC’s sustainability principles (for example, generating 14,600 new car trips per day). Planning sent the project on to the City Council for committee hearings in November and to its historic rejection by the full council on December 9.

The Next Steps

Even as KARA and its allies celebrated (and as the Real Estate Board of New York threatened retribution), members voiced their frustration at having been able to block a bad project, but unable to transform it into a good one. They didn't lack of a vision of their own -- though in hindsight, Farkas and others wondered whether the community caved too quickly on letting retail dominate the armory mix. But the City Charter provides only the flimsiest tools -- 197a plans -- for proactive community planning. Instead, the land use process puts developers and mayoral agencies in the driver's seat, and leaves communities, community boards and the City Council strapped firmly into the back seat. Will any effort at charter revision open an opportunity to change this dynamic?