New Homes for the Arts

It has all the appearances of an arts boom.

The Museum of Modern Art opened its new space last week, to widespread media attention, most of it laudatory. Building the new museum cost $425 million, took more than two years and will boost the price of museum admission to $20.

But MoMA is not alone among the city's art institutions in seeking new quarters to meet changing demands of artists and audiences.

- The Dia Arts Foundation opened a large exhibition space in Beacon New York to display its contemporary art.

- Last month, the Rubin Museum of Himalayan art moved into what had been Barney's in Chelsea

- The Brooklyn Museum of Art last spring revealed its revamped museum, complete with a fountain and grand new plaza in front.

- A $75 million Visual and Performing Arts Library is planned for downtown Brooklyn, near the Brooklyn Academy of Music.

- The Joyce Theater will get performance space downtown as part of the plans for rebuilding Lower Manhattan.

- Also in Lower Manhattan, the Signature Theater will open a performing-arts complex of three theaters, a bookstore and a café.

- The New York City Opera, which also wanted to move downtown, was rebuffed and is now seeking another home that will enable it to leave its current quarters in Lincoln Center.

But, despite the building boom, the past few years have presented challenges to cultural groups in New York City. Leaders of arts institutions speak, albeit gingerly, about declines in attendance and tightening budgets since September 11, 2001. "Since September 11, 2001, there seems to have been a seismic change in audience patterns," said Paul Kellogg of the New York City Opera. "Subscriptions are down across the country, even the world. Single ticket buyers are not buying ahead and they are attending fewer performances."

At a recent breakfast sponsored by Crain's New York, leaders of four top cultural institutions described their efforts, despite such difficulties, to expand and change for the 21st century.

Barry Grove: The Manhattan Theater Club Revamps a Legendary Theater

Paul Kellogg: Seeking a New Space for the New York City Opera

Glenn Lowry: The Museum of Modern Arts' New Home

Linda Shelton: Creating a Center for Dance in Lower Manhattan

Â

The Filtration Plant Deal in the Bronx: Flawed Planning, Environmental Injustice

The City of New York is planning to write a fat $243 million check for parks in the Bronx. But before park lovers uncork the champagne, take another look. This is a payoff for the city's plan to dig up nine acres of Van Cortland Park so they can build an underground water filtration plant. But the million dollar deal is deeply flawed as public policy and the project is the latest in a long line of environmental injustices, having a negative impact on the neighborhood of Norwood.

Gotham Gazette's Anne Schwartz recently raised questions about the filtration plant proposal and park swap.

A memorandum of understanding signed by the mayor and city council in September of this year appropriates an unprecedented amount of city funds to fix up Bronx parks. "This is something we want to praise," says Christian DiPalermo, Director of New Yorkers for Parks, "even though the process used for making the decisions wasn't inclusive."

But the most troubling part of this deal is that most of the funds will get sprinkled around the Bronx like fairy dust while the neighborhood of Norwood where the filtration plant is to be located gets all the truck traffic, noise, and pollution. "In most cases where parkland is taken," says DiPalermo, "funds are spent in the affected area. While the project is in Van Cortland Park, most of the money will be spent elsewhere." In addition, "city money is going to the state, for Roberto Clemente State Park" while the state already gets more taxes from the city than it spends.

Another problematic part of the deal is the $6 million allocated for McCombs Dam Park. This park is located right next to Yankee Stadium and is the proposed site for a new stadium. Details of the stadium plan haven't been made public, but presumably the McCombs Dam Park would be relocated somewhere nearby. Even if that's the case, says DiPalermo, the parks money should go to parks, not "a deal to keep the Yankees." But then sneaking subsidies to stadiums seems to be one of this administration's nasty habits.

In the discussion about where to spend the money, the point of departure for planning ought to be the recreational needs of residents, not the deficits in the Parks Department budget. The city's planners don't systematically track recreational needs, so they don't even have the basic information they need to do that. No one even asked what kind of recreational facilities are needed in Norwood. Planning for parks is increasingly driven by the logic of big projects, private conservancies, and one-time infusions of largesse. Many of these big projects - stadiums, arenas, and private concessions - make millions of people passive spectators while a handful of athletes entertain. They reinforce chronic syndromes such as obesity that cripple people young and old. Recreation they're not.

Norwood and Environmental Injustice

The proposed plant is anything but a good deal for the 30,000 people who live in Norwood, the majority of them people with low-incomes and people of color. According to the local youth group The Cove, "The construction of a water filtration plant will cause a negative recreational, educational, ecological, health and life-threatening environment for the most precious resource, our children."

While every New Yorker may benefit from cleaner water (though there are still some questions whether filtration is needed in the first place), and lots of people in the Bronx will have their parks fixed up, the people who lose are all in one Bronx neighborhood. They will lose their parkland, suffer through up to a decade of heavy construction, and get only a fraction of the $243 million. Of all the neighborhoods surrounding the park, they have the largest youth population and greatest need for recreational facilities. Their closest green neighbors are a golf course and a cemetery.

While the city's giant environmental impact study claims the plant will have no significant negative effect on the surrounding neighborhood, to those familiar with the city's policies for siting major infrastructure it raises the specter of environmental injustice.

Why choose the Van Cortland Park site over a similar site in Eastview, in Westchester County, on land the city owns and has been planning to use for years to build the filtration plant? Why did the city decide they would instead relocate a perfectly fine golf driving range, blast 80 feet into bedrock, fill the hole with a filtration plant, then put the driving range back on top - when they could have just built an above-ground building in Eastview? The city claims that at the Van Cortland site they wouldn't have to build as many tunnels as Eastview. Yet the costs for construction at the two sites, and the projected operating costs, are pretty much the same.

Norwood activists want to know what the project's planners had in mind when they made the decision so these questions can be answered. But what we may have here is a classic case of "color blindness" - a failure to even consider the disparate impact of facility siting on low-income communities of color.

One of the reasons for the emergence of environmental justice claims by city neighborhoods over the last couple of decades has been the professed color blindness of city officials when they locate such facilities. The preferred sites are usually those where the land in the surrounding neighborhood is cheapest and, thus, where the impact on land values and property owners will be least. The planners are blind to the people who live and work there.

The environmental impact study for the Van Cortland plant appears to have come after the siting decision was made. It includes a section that is supposed to consider the disparate impact on "minority" communities. But these declarations are usually after-thoughts and often not taken seriously. The study notes that the neighborhood near the site is 75 percent "minority" (this term is from another epoch when people of color were a minority of the city's population, and to continue to use it only sows confusion). They even state that the area around the Eastview site is 60 percent "minority," making it appear that the two neighborhoods are comparable.

But what they don't consider important is that there are only about 3,000 people within a half-mile radius of the Eastview site, and these "minorities" appear to be very rich, even richer than the Westchester average. (However, one neighborhood activist points to a prison near the site and believes that's where the "minorities" are). The folks around the Eastview site had a median household income of over $77,000 at the last census, over a fifth higher than the Westchester County figure and more than twice the figure for Norwood. Race isn't the only factor in environmental justice claims; it's the intersection of race and economics that makes color blindness so damaging.

The other thing that is never mentioned by the project planners is the rapidly rising land values around the Eastview site, spurred by large-scale commercial and retail development in the area. Were the city's planners thinking more like real estate developers than guardians of the public trust when they selected the Van Cortland site? This fits the approach now taken with parkland: save the choicest pieces for income-generating activities and dump on the rest.

Norwood activists worry that if the filtration plant is built in their neighborhood the city's Department of Environmental Protection (DEP) won't do a good job of maintenance. They worry about the storage of chemicals and daily truck traffic. If the surrounding land and people are seen as having little value, why should those charged with maintenance be careful? Remember the department's lousy performance with their sewage treatment plants in West Harlem and Greenpoint that led them into intense court battles? More recently the department pleaded guilty in federal court to discharging mercury-contaminated water into an upstate reservoir for two years, and is still under the watchful eyes of a court monitor. Who will watch them in the Bronx?

For Norwood residents, the only section of the park that's accessible to them on foot is the one where the plant is proposed. Almost all of Van Cortland Park's facilities are on the west side, near Riverdale, where much wealthier, more mobile households can reach them by car. The Riverdale side of the park stands to get $18 million from the city's deal. It's bad enough that more land in city parks is getting handed over to paying concessions like golf courses. But the city shouldn't dump on the rest, then reward the parks that are backyards for the rich.

Tom Angotti is Professor of Urban Affairs and Planning at Hunter College, City University of NY, editor of Progressive Planning Magazine, and a member of the Task Force on Community-based Planning.Â

The Housing Problems Of Immigrants

Illegal immigrants are probably the most vulnerable people when it comes to housing. They are easy targets for exploitative landlords who threaten reporting them to immigration authorities if they try to assert their rights. Unaware of laws that set standards for apartment conditions – and intimidated by landlords – they hesitate to complain, and often live in miserable conditions, going months without heat or hot water.

If they do actually find themselves in Housing Court they often face a double whammy: They do not understand the language being spoken, and they also do not understand the legal system they are dealing with – a system that regularly confounds English-speaking legal citizens who do know something about the law. Like most tenants, they represent themselves at the court, and their opposition is an attorney, highly educated and well-versed in the language of the court.

These problems have inspired advocates from immigrant organizations and housing organizations to come together. Responding to a call from the New York Immigration Coalition, advocates are searching for answers to the housing problems immigrants face. Comprising 40 percent of New Yorkers, immigrants’ housing problems are substantial.

But there are few easy answers. Consider the case of West African immigrant Safiatou Diallo, a slight woman with three children. She was in the Housing Court recently trying to figure out if she could continue living in the two-bedroom Bronx apartment she has called home for the last three years. It was doubtful.

Although the apartment was rent stabilized, a status that offers tenants many protections, Diallo was never on the lease and only distantly related to the man who was. He disappeared about four months ago and Diallo, who occasionally earns some money braiding hair in Harlem, has only a fraction of the back rent the landlord was seeking and makes not nearly enough to pay the $888 monthly rent.

Diallo does not speak a word of English. In the village in the Ivory Coast where she grew up, housing conflicts are resolved by the village chief and almost never would result in someone becoming homeless.

“Maybe I can find a roommate,” she said in her native language, as she considered her options. “I have nowhere to go otherwise.”

But with no right to the apartment and the landlord’s attorney unwilling to even consider giving her a lease, Diallo’s idea was a non-starter.

The coalition’s project was launched after focus groups comprised of immigrants identified a variety of housing issues. The groups varied by nationality, gender, age, immigration status and area of the city, from senior citizens in Chinatown to undocumented West Africans in Harlem to Arabic-speaking women in Brooklyn.

“What was interesting was that although there was a unified voice for affordable housing, there were unique issues for each group,” said Ben Ross of the New York Immigrant Coalition.

“In the South Asian, Arabic-speaking community, there was a lot of landlord harassment and discrimination,” Ross said. “In the undocumented Mexican community, there were a lot of people who did not know their rights and did not have the materials to provide housing assistance.

“In the communities that were more established, like Chinatown and Dominicans in Washington Heights, they knew a lot but had language access barriers.”

Since then, Ross has organized meetings that have included a wide variety of groups working with immigrants and others working with tenants. Just connecting these groups was a step forward. At the first meeting, advocates exchanged business cards, probably as important a step as the discussion of problems for immigrants and tenants.

“We need to link the two advocate worlds,” said Monica Tarazi, New York director of the American-Arab Anti-Discrimination Committee. “The immigrant rights community has not really focused on housing issues and the housing advocate world has not really focused on immigrant rights. If they have, we have not really worked together.”

The expertise, connections and experience of advocates in both worlds will be extended as a result. Already, housing advocates are setting up training workshops on tenant rights. And immigrant advocates are helping housing advocates recognize the problems immigrants face, such as language barriers at Housing Court.

As much as the advocates’ collaboration will help immigrants understand their rights, however, many have already learned that that may not be enough. Housing advocates are hoping that helping organizations that help immigrants will bring more people out to rally for better housing code enforcement, more just enforcement of housing laws, creation and preservation of affordable housing and strengthening of the rent stabilization law.

Manuel Castro, the environmental and housing organizer at Brooklyn’s Make the Road by Walking advocacy organization, said his organization already recognized that more could be done by uniting immigrants under the housing banner as well as informing them.

“We’ve been working on trying to put up legislation and working with different groups,” he said. “We are in agreement with HPD on inspections – we need more comprehensive inspections. But even though people get inspections, that doesn’t mean repairs are going to get made.”

Joe Lamport is the assistant director of the City-Wide Task Force on Housing Court, a coalition of community housing organizations.

Rezoning Proposals Squeeze Out Affordable Housing From Both Ends

Changes to the city’s zoning code are now helping to put affordable housing in a double vise. On the one hand, new zoning is keeping affordable housing out of well-to-do homeowner neighborhoods that have plenty of space for new housing. On the other hand, new zoning is pushing affordable rental housing out of neighborhoods where it already exists. Soon there will be no place to live in New York City for anyone making less than $100,000 a year. The city will be a wealthy enclave, like a medieval fortress protected from incursions by those who live outside the walls. Is this the vision behind the zoning policies of our billionaire mayor, or is it just the work of the city’s planners? No matter who is responsible, we should all take a look at what’s happening if we want to stick around.

Zoning to Preserve Neighborhoods

Jamaica Hill is a quiet neighborhood of one- and two-family homes in Queens. The homeowners want to keep it that way. They are afraid that speculators will see their rising property values, move into the neighborhood, buy up homes and convert them to apartments. Loose zoning regulations have produced just this scenario in many Queens neighborhoods.

So the Department of City Planning came to the rescue. In their Jamaica Hill proposal, the city’s planners warn that without a zoning change “existing single family homes can be replaced with attached, multifamily structures that would be out of context.” So they propose to tighten up those loose zoning rules, meaning the speculators will have to go somewhere else.

Jamaica Hills is the latest in a string of lower density rezonings in the outer boroughs to protect neighborhoods from unwanted development. “Contextual” zoning rules aim to ensure that the size and scale of new development is consistent with the existing neighborhood. To the homeowners it makes a lot of sense.

The Department of City Planning is currently rezoning selected homeowner neighborhoods all over the outer boroughs to preserve what they call the “neighborhood character.” For example, the city’s planners propose to strengthen the Special Natural Area District, which applies to portions of Staten Island, Riverdale in the Bronx, and a piece of northeast Queens. In North Riverdale, the planners proposed to rezone a homeowner neighborhood to help preserve it, and Bronx Community Board 8 unanimously concurred; the rezoning is expected to pass the land use review process shortly. Because they reduce the density of potential new development, these changes are called “downzoning.” Conversely, zoning to increase density is called “upzoning.”

The Neighborhoods Not Preserved

The agency is not so quick when it comes to preserving neighborhoods with renters, industry, and lower-income people. Preservation seems to be a privilege reserved for exclusive upper-income neighborhoods of homeowners. If you look at the ethnic makeup of the privileged neighborhoods it should not be surprising that most, though not all, are lily white.

The planning agency’s double standard on preservation also applies to community plans. The city’s planners are moving quickly to implement a community plan done by upscale homeowner neighborhoods in Queens, Riverdale and Staten Island, while at the same time they are overturning the community plan of an older working class neighborhood in Brooklyn.

The neighborhoods of Greenpoint and Williamsburg in Brooklyn have seen their plans turned upside down by the Department of City Planning. These two adjacent neighborhoods completed plans for revitalization of their East River waterfront land that were approved by the City Planning Commission and City Council only a few years ago. The plans called for a mixture of residential and small industrial uses on the waterfront at a scale consistent with the existing neighborhood of two-four story row houses. Both plans intended to make it difficult for noxious industrial uses like waste transfer stations and power plants to locate on the waterfront but wanted to keep non-polluting small-scale industries that provide jobs for many local residents.

Just like the folks in Jamaica Hills, the community planners in Brooklyn wanted to preserve the “neighborhood character.” They also wanted to open up opportunities for new affordable housing that wouldn’t jack up property values so much that current residents would be forced to move.

Instead of following the plan that the city approved, the Department of City Planning has now proposed a massive upzoning of the waterfront, going from the medium density R6 to a high density R8. In addition, they want to allow new residential development in upland zones that now permit only industry. The inevitable effect of this in a neighborhood now undergoing severe gentrification will be to chase out existing industries and make the neighborhood another monolithic upscale bedroom community. The rezoning began the official land use review procedure on October 4 and is now under consideration by Brooklyn’s Community Board One.

When you put these two rezoning strategies together, new affordable housing will be banned both from low-density homeowner neighborhoods and from more centrally-located neighborhoods. So where will the “affordable” housing promised in the mayor’s housing plan be built? It will have to be tucked away in the corners of the giant real estate schemes for Midtown West, lower Manhattan, downtown Brooklyn, and Queens West, so small they will be unnoticeable

Tom Angotti is Professor of Urban Affairs and Planning at Hunter College, City University of NY, editor of Progressive Planning Magazine, and a member of the Task Force on Community-based Planning.

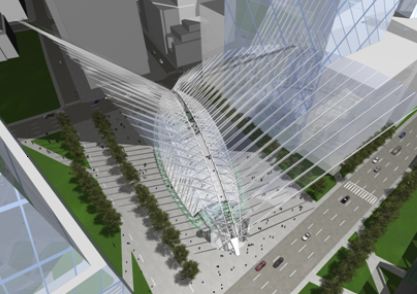

WTC Architects

|

|

This month at Learning from Lower Manhattan, a national conference presented by the American Institute of Architects New York Chapter, Daniel Libeskind, the designer of the master plan for Ground Zero, Michael Arad, who designed the Ground Zero memorial, and Santiago Calatrava, the architect of the transportation hub at the former World Trade Center site, spoke together in person for the first time. The discussion was led by Leonard Lopate of WNYC radio.

After presenting their individual projects, the architects spoke about

- Connecting Ground Zero to lower Manhattan,

- Building on a site with both commercial and emotional significance,

- Whether too many distinctive buildings will clutter Ground Zero,

- The issues surrounding the creation of the cultural complex on the site, and

- Using symbols in architecture.

An edited transcript is posted below.

Leonard Lopate: Gentleman, I'm told that this is the first time that all three of you have sat down to talk to one another. Is that true?

Michael Arad - I think all at once, yeah.

Lopate: You've met singly but never all at once. Is that typical on a project of this size?

Daniel Libeskind: - I think it's understandable. There are so many different components, everyone has to develop them to a point, and then they can speak in dialogue to one another. I think that it's not unusual in a project the size and the complexity of this one. There is a time for that, and we still have time. I'm sure that in the coming months there will be much more intensity as the projects really come to a critical point of implementation.

Lopate: Before I go on to my questions, now that you're all together, and you have the opportunity, is there anything you'd like to ask one another? Have you been thinking "If I ever get the chance to sit down with Santiago I would like to ask him a question."

Arad - As a group we haven't all sat down, but I've met with Daniel a number of times; I've met with Calatrava as well. But I will pass it to my elders.

Libeskind - Don't get the impression that we are not in close communication; we are. We are not often on a stage together because of the obvious - there are so many things happening. But we are in close communication about the development of these projects.

CONNECTING GROUND ZERO TO DOWNTOWN MANHATTAN

Lopate: The feeling I got from all three of your presentations is that you're not just concerned with how your plans will interact with each other, but how the whole will interact with the immediate area, the downtown area in general. Yesterday, one of the people here said to me that his concern was whether he is going to be able to get to Chinatown from the World Trade Center site without going through Brooklyn. Are you really thinking about that; are you thinking all the way to South Street Seaport and Chinatown?

Libeskind - Absolutely. We are reintegrating the site in a way that it was not before 9/11. Before 9/11, as you know, the World Trade Center plaza was an obstacle, a blockage, a huge podium. There was very little retail on the streets, all the retail was underground. We have been making an effort to put retail on the streets, which is not always easy. As the Port Authority understands, there are already people underground; it is an easy way to sell things.

But we are making an effort to create vibrant streets, streets that are interesting to walk, that do not just connect points. With the memorial, with the station, these are streets that are going to have hundreds of thousands of people on them.

Lopate: -- People were really unhappy with the way the old World Trade Center worked. That plaza was a dead space, and it's been determined, I gather, that for the first time in 37 years New York City owns those streets. Will they have a say in how the streets will work with this?

Arad - I can really speak to a more limited area than Daniel, in the sense that I am working on the more limited area of the memorial. We're working with transportation planners, we're looking at what the pedestrian experience is, what the expected number of visitors to the memorial is every year, and how many people come to work here every day. We're planning very carefully how to tie this site back into the neighborhood; how to make this a significant place for downtown residents while also maintaining the sense of a space that is sacred, and has great importance for the memorial. Finding the right way to balance these concerns is something we are doing every day.

The paths, for example, for tourists, down towards Battery Park, coming through the site, coming from the train station, have to balance with the people going to work, going to the financial center.

Lopate: Santiago, when you showed us the plans for that beautiful housing development you have designed, were you seeing it as connected with your PATH station?

Santiago Calatrava - Well, in my presentation I showed how I approach a design: trying to learn from examples in New York. However, I would have to say my background is European. I look at New York today as a city that could be a European city. I would like to say that my vision of the city is much more related to plazas, as elements to build a city. Everything we have done to build the station goes in this direction. In terms of recreating, you see a place which could in a way have the quality of the plaza; I have a big hope in seeing the 11th of September Plaza, which I'm not designing, but which I think is very important for the project.

The consequences that this area will have to go as far as, without any doubt, to the place where we are doing that tower, and also to the waterfront with the whole storybook background of the boats, and Brooklyn, and so on. I still have a lot of difficulties to understand the city -

BUILDING FOR COMMERCE; BUILDING FOR EMOTION

Lopate: Paul Goldberger has written, I'm quoting "the genuine craving for an architectural response to the crisis, a wish for architectural aesthetics to heal a broken world." Has that been a problem from the start, that the site had to satisfy not just commercial needs but also emotional needs? I throw this out to all of you, because I do believe that all of you have thought of this.

Libeskind - I do believe that architectural is not just intellectual - it is an emotional art; it is communicative art. Particularly on this ground, I believe that every building, and every prosaic activity will have a resonance that goes beyond whatever it is. In that sense, I believe there is nothing on the site - not even an entrance to a building - that does not require special thought. It has to relate to everything else on the site, since this is not just a site that is to be developed for commercial reasons.

Lopate: People see it as sacred ground.

Libeskind - And it is.

Arad - I'm from Jersualem and -

Lopate: Is anyone on this stage born in the United States except me?

Arad - Well, we are in New York.

In something Santiago just said about a European city, I was thinking about home. This issue of, I don't want to say religion, but spirituality. How do we deal with that in a city like New York? To me, lower Manhattan became a very spiritual place after 9/11. I lived downtown , and I remember being in that area that was cordoned off, and not being able to sleep at night. I got on my bicycle and rode around and saw that late night response of people just standing around in a place like Washington Square Park, and the vigils of strangers coming together. If I am able to capture some of that spirit in the design in the plaza, in creating a space that is different from other places in New York -

Lopate: -- Santiago, do you think that the same thing will happen in Madrid when the train stations that were blown up are rebuilt? Will that be seen as sacred ground, or did 9/11 take on a significance that was a little different from the terror acts afterward?

Calatrava - I was in Madrid the 11th of March, the day of the attack, so I followed a bit from close in the first moments. What has happened since then I have to say I am not aware of what the people in Madrid want to do today. I think they tried to overcome the problem in another way. Pyschologically, maybe they used the Spanish way to think. I say that because Spain has come from a dictatorship into a pure democracy, we still have work to do. Maybe we are in this kind of amnesia; the thing is different.

Lopate: Daniel, in the Winter Garden of the World Financial Center is an exhibition - From Recovery to Renewal by the Lower Manhattan Development Corporation. How instructive is the comparison of the two models that show the plan you envisioned in 2003 and the design as its evolved - the twisting Freedom Tower, the transportation hub, and the landscaped memorial that turns the Twin Tower outlines into water -filled voids.

Depiction of memorial

Libeskind - I think it's a confirmation of the success of the consensus that the master plan has brought to so many different issues. We are only a year and a half after that competition, and the master plan has created a consensus between those various stakeholders. This site was not declared a site that is controlled by a single authority, or a single person, or a single political power. It's a site that is developing within the complexity of the city, and within the complexity of the marketplace, and within the complexity of what it means symbolically and spiritually to the world. As such, it's kind of an instruction of how to develop a city.

We often concentrate on aesthetic issues: is a tower going straight up, or is it twisting? But what relationship does that have to do with the true fundamental issues of the city? We don't discuss that.

Often people see those two pictures and they say "Mr. Libeskind, is that the same picture?" and I say "yes it is, because the function of shaping this large space was not conceived in the 20th century, old master planning way, where you do a plot plan and you say "build up to this height, build up to that height." That is the way Potsdamer Platz in Berlin was created, which I think is in the end not a successful urban vehicle. It doesn't have much life. It has nice buildings from famous architects from all over the world, but it doesn't sing.

I thought we should do something different here. We should allow a balance between individual freedom, which has to be the message of the site, and also something in the end that delivers a coordinated and integrated plan that is a composition that has integrity. That balance, between flexibility and openness on one hand, and definition and precision on the other, is a contemporary 21st century idea for developing a site plan.

Lopate: Is the plaza with the Wedge of Light, is that still in place?

Libeskind - Not only is it still in place, Santiago Calatrava's interpretation of it has made it much more profound. It goes beyond simply defining an edge; it creates a central point where all the people using the station will be a part of a kind of unfolding drama in the skies of New York no matter the weather. I think it shows that with creative ingenuity and great architecture, a master plan can really flourish.

Lopate: It's been reported that when you learned of the vote in favor of Michael's memorial plan that you were horrified. What bothered you -

Libeskind - No! That's absolutely not true. All sorts of things are attributed in the press to me which are not true. In fact, when I saw Michael's project people said "aren't you horrified?" I said no, because if you look at what he has done, he has followed every master planning criteria: he has gone down to 35 feet below street level, and at bedrock at other points. He has created a space that is meaningful, that has a profound relationship to the Twin Towers.

The problem was that many people thought that what they saw for the master plan was a design for things. Of course it is a design for the spaces, but it is not a design for the buildings, or for each individual structure. I thought Michael's memorial was extraordinarily sensitive, simple, something that will really contribute to that site being an important one.

Lopate: But Michael, didn't you eliminate the cultural buildings, and even the trees from the block initially?

Arad - I can understand Daniel's take on this, especially the highlighting of differences. But I think there are many issues which the master plan set which were the principles from which I found guidance in my efforts to think about the site. The street grid was a cue, which I took as something that meant that the site must be reintegrated into the city.

The cultural buildings were an issue. The idea of actually bringing cultural buildings to the site is something I find extremely important, and will change the nature of the site. Finding the right way to do it within the designs as they evolve is a challenge.

The architects for these buildings - I think the short list just came out today -- will be involved in this. Things will continue to evolve. The question is are the basic and most important tenants of creating a memorial there, and will the site be preserved? I think it will be.

Lopate: Well I want to get to the cultural buildings in a moment but how do you think the slurry wall will end up being used? You didn't want to actually use it all originally, did you?

Arad: I didn't plan to develop it. But right now it is a major component of the underground museum, the Memorial Center. I am focusing for the most part on the development of the memorial. There will be another architect who will be designing the memorial center.

Lopate: And that's where it will be. It won't be visible?

Arad: The top of the wall is just below the level of the plaza. So the question is how it will be visible - perhaps through skylights, perhaps we'll have openings in the plaza itself.

Lopate: Is there still a plan to create a bus garage below this whole thing?

Libeskind: No, certainly not. I think one of the achievements of the last month was being able to remove the complex infrastructure and much of the security concerns from below the memorial . The memorial that is being designed can reach bedrock, and can have freedom to develop spaces for the public.

And that is not a small achievement because we were also able to create a new park which was not part of the original competition. The site is on Liberty Street, a park for the neighborhood. And I just want to remind all of you that the memorial is 4.7 acres out of the 16 acre site. And if you take the streets, public spaces, the wedge of light, there are probably just 10 acres of public space created on the site. So it's necessary to ask the question how do you create public space and also accommodate the developers and contract which calls for 10 million square feet of commercial density on the site.

TOO MANY STRIKING BUILDINGS AT GROUND ZERO?

|

Lopate: Santiago, David Dunlap of the New York Times wrote that you have produced such a striking design at the PATH terminal that it almost appears as if there could be too many distinctive buildings on one intersection. He says imagine Grand Central Terminal and the New York Public Library across the street from one another. There is a concern here that this whole thing could turn out to be a mish-mosh of great buildings. Was that a concern for you as well? Have you made plans to connect the PATH station to the other transportation, the more practical stuff, like the MTA's Fulton Street hub?

Calatrava: There are two things: the one is the practical aspect, as you say, and the other is the way you go into a design. I keep always distinguishing very much between form and content. I'm from an old school, a Greek school, a Platonic school, which says you should be making a difference between the body and the soul of the thing. So finally in my mind there is a kind of interpretation of the area. I try to identify a scheme with a certain scale in which the building fits.

The problem of the scale is a major problem in terms of the space of buildings and kind of building we are putting in. It's a link between the persons moving around. Then we discuss also the relation between this building and the surrounding buildings many times.

I think it's very important to understand that the whole open space doesn't go until South Street. It appears many times in the configuration of the plans that it goes until the World Financial Center. If you have in front of you a model, on a very small scale, then you can see that the space you have is much larger than the space truly delineated by the footprints of the towers and the area where the garden and plaza should be. But it is much larger.

And the center of this estate is the corner to the east of the September plaza, with the station and the cultural buildings. So it seems to me, that there is a capacity there to reconsider the relation between those three important buildings, particularly the art performing center and the museum, and situate them in relation, not only to the station, which is my problem, but also to the rest of the configuration.

And it appears from the point of view, , and this is another aspect, the volumes of those cultural buildings that are just gravitating over the mezzanine of the PATH station are so tremendous that if we have to carry them, all the transparency we want to achieve in the mezzanine will be very deeply compromised. And the idea of bringing daily life into the clouds will also be very deeply compromised. So finally I think that there is a way looking forward, working together to reconsider the situation since we are all partners, committed, and instrumented by idea of articulating buildings in harmony and working in consequent with a master plan.

Lopate: Actually someone just sent up a card from the audience. It says 'does the siting of the museum complex in the master plan create any problems with the transportation hub as you've designed it." You kind of answered the question but that was a concern of yours as well Daniel?

Libeskind: It's a problem not to see each project just as being by itself. There is a station, well people say "oh, there is a station." There is a memorial, there is a tower, there is another tower, there are 5 towers all together, there are public spaces, there are the streets, there are things under the street, there are parks and so on and vistas and perspectives. It is very important not to reduce music to a single note, to a single series of notes, discordant or uncoordinated, because the entire efficacy of the master plan, of the city, is how these things go together .

I don't have any of the worries of Mr. Dunlap that New York will be too interesting. New York needs an interesting set of spaces. Ground Zero needs to be developed in a 21st century way, not just the dark alleys that we know from Wall Street. And therefore I think New Yorkers will see something very different on the site, very exciting, and also very spiritual.

Lopate: But isn't there also a danger of this looking like a sculpture garden where you have realistic and abstract sculptures that have nothing in common with each other all just sitting side by side of each other?

Libeskind: It's been said that every building in New York is a piece of sculpture with plumbing. They happen to be sculpted in a certain era, a certain type. I think the architecture of Santiago Calatrava and the memorial of Michael Arad, and whoever does the cultural buildings, I think there will be both a distance and an identity, both a relationship and an individuality. That balance will create a place that is attractive over the years.

CULTURAL BUILDINGS AT GROUND ZERO

Lopate: Keven Rampe, the president of Lower Manhattan Development Corporation announced the finalists for the performing arts center and museum yesterday, and the developent corporation says that risk taking was a quality it sought when choosing architects for the cultural buildings. You Daniel, are one of the finalists for the performing center aren't you? Hadn't you expressed a preference for designing the museum?

Libeskind: No I am so delighted to be involved in this, being already involved in this grand site it's such a privilege. It's also a humbling experience because we all know that we are not just there in a solitary way, that we all have to work together, closely and in a profound way. I think that's also a reflection of how great cities are built. There are boring cities, and unfortunately, often we admire cities built by dictators that have been imposed on the public and we later forget what they really mean. But a city done this way, in turmoil and complexity and energy, and with fights and anxieties but also communication will turn out well.

Lopate: It can also turn out to look like Toronto; I don't know if that's so great. You decided not to enter a proposal, Michael.

Arad: My hands are full.

Lopate: Santiago, did you also apply for either museum or performing center?

Calatrava: No.

Lopate: So your hands are full as well.

The cultural buildings are expected to be completed by 2009 and I was looking at them, they include six theaters ranging from 99 to 1,000 seats each, large galleries for drawings and artifacts related to freedom, a pilates studio, we couldn't have left one out. When I think of all the organizations that wanted to get in and the pilates people got in…There also will be gift shops, bookstores, a dance rehearsal studio visible to pedestrians, special events space with a kitchen on a terrace overlooking the site, a ceremonial space where naturalized citizens can be sworn in, and then there will be the performing arts complex that will have the Joyce Theater and the Signature Theater Company as well. They've been moved a bit from the original haven't they, and been made a little more compact?

Libeskind: There have been, of course, a lot of discussions, and they are not my decisions, these are decisions of many others, of the City of New York and the Lower Manhattan Development Corporation. How large should the cultural facilities be, how realistic is it to have them programmatically related, and in what way should they be related?

As master planners, we did a lot of work in terms of showing the possibilities. Remember the New York City Opera wanted to be on the site. Many organizations wanted to be. There was a consensus on the scale and content of the cultural facilities; of course this was a decision made by the Lower Manhattan Development Corporation and by others. Those decisions have been made and now we are moving forward on those institutions.

Lopate: Well, the New York Times wondered if any architect would risk challenging the kind of thinking that requires locating the museum complex within the northeast corner of the memorial precinct. What was your thinking in placing the complex where you did?

Libeskind: It was very simple I think. When you take the sequence of Lower Manhattan from north to south, east to west, you see that the intersection of Greenwich and Fulton Street; it is an important nexus. It's not just another intersection within the grid, but it's important in pointing, in thinking towards the Hudson River and the entire shoreline. We often forget how close we are between the East River and the Hudson River when we are at the point. It is a true point of meeting, September 11 Place is a true place of meeting.

We also have the Freedom Tower, on the western side we have the memorial, we have busy streets on the eastern side. So the thinking was a very simple one. One has to create a medium or mediation between the sacred nature - and the very quiet and sad nature - there will forever be of the memorial, and the vitality of streets that are unabashedly New York, where you can see advertising, people, and retail. We don't want the sadness of September 11, which is eternal, to become the sadness of lower Manhattan. That is the strategy. There was a lot of thinking to where those buildings were placed. It was not arbitrary; it was not just forms and functions. It was "how do you strategize by creating a city that is vibrant and that at the same time never forgets 9/11?"

Lopate: The museum will be divided between a larger international Freedom Center and a smaller Drawing Center, which sounds like apples and oranges to me. I'm sure some architects will think of separating the two because it sounds hard to integrate them. Will there be resistance to changing the whole thing after Kevin Rampe says that the intersection of Fulton and Greenwich Street is the 100 percent corner because the museum will share it with the performing arts center, and the PATH terminal, and the transportation hub, and all the stores and hotels and everything else?

Libeskind: Well I think there is a difference in content and amount of space needed for the Drawing Center and the Freedom Center. These are institutions of very different nature, requiring different spaces. It is not that they are two equal institutions. The Drawing Center is not at the same scale as the Freedom Center and therefore requires a different architectural response.

|

|

Lopate: If the museum were removed from the corner ,one effect might be the creation of visual access from Santiago's Path Terminal to the barrel-vaulted skylight over the Winter Garden at Battery Park City. Since many visitors approach from that direction it has been proposed that such a clearing would create a break in the dense fabric that lower Manhattan presents. Is that something you would like to see Santiago?

Calatrava: I come back to the question of how you read the city. I'd like to underline the aspect , particularly in European cities , the importance of the plaza is so high that you can even get a city of plazas without streets. So it also has a signification as much as you can speak from past tense as a kind of metaphysical understanding, a poetic understanding, you can speak of about voids -

Lopate: There are parts that attract people and there are parts that don't -

Calatrava: No, no. Let me be a little more peripatetic, it will take just a minute. The situation is this, in New York you see corners and corner situations, and crossing. It is very habitual; the city is almost a grid. But also you see whenever you discover one of those plazas, it appears as an oasis, an unbelievable appearance. The void is also very appreciated because it delivers a very global view, it delivers a public ground, maybe full of trees or whatever.

I could imagine that effectively the density that you create in a corner of the composition among all these tall buildings - putting all three of those buildings around the corner - is almost too much. So I understand very well the statement of Dunlap. And indeed it is possible in the letter of the whole situation that the hierarchy of the buildings can be related to each other and, in a way, to even the absence of the memorial.

It is now the moment to discuss what will be soon. Because as I say I always approach the problematical design in the context very much inspired by the context and content of the master plan. The modernity of this master plan, according to my capacity of judgment , gives signification to the things. Which is very different, very modern, and very few times done.

You see, as it has been said here before, bringing it up in a level of discussion in which you can start speaking about absence, about void, about cutting a piece of the sky in Manhattan. This is the magic context in which we are moving. However, I think we should do whatever we can, get feedback, reposition ourselves in a dialogue in order to deliver and be conscious and be responsible in front of those who will judge us.

Arad: I want to add to Santiago's comments. While I agree with all of them, I wanted to mention Union Square, Washington Square, and Bryant Park as good examples here in New York of the type of space that I think Santiago is referring to.

BUILDING SYMBOLICALLY

Lopate: Daniel, you originally had gardens in the open-air structure above the enclosed portion of the Freedom Tower. And you've taken them out. Do you know if David Childs is willing to drop the wind turbines which have upset so many bird lovers?

Libeskind: No. It was an interesting compromise because the gardens which I proposed originally to restore the skyline of New York were something about healing, something very positive, something that is inspiring when you look at the sky. But I also thought of them as an ecological component. It was not just a symbolic component of nature. But what can we do, how can we mark a new awareness of the sky in the 21st century? And I think as someone's response, the windmills were a very inventive response . It wasn't literally the garden, but it had a lot to do with harnessing energy and how to create something that connects that great height with the roof planes at a much lower height. I actually thought it was a very good idea.

Lopate: But it might kill a lot of birds, I've been told, and that is a concern. Someone asked me if this is all a matter of symbols and how much was someone as hard nosed as Larry Silverstein willing to finance symbols?

Libeskind: Well you have to ask Mr. Silverstein , but I don't think that Mr. Silverstein does something because it is symbolic, he does things that are profitable. The amount of energy that will be generated by those windmills is very impressive, at least in the design that I stood by. It is a very pragmatic solution to energy needs.

Lopate: You said in your presentation that the Freedom Tower will be 1,776 feet high but the Times reports that it could be higher, up to 2,000 feet, or we hope if were sticking to dates, 2001 feet. Does it really matter?

Libeskind: Yes, it does matter. Often people think of the height of 1,776 feet and a Wedge of Light and the memorial as just symbols, but let's talk about practical things. The amount of height that this tower reaches has an urban application. We don't want to dwarf the memorial; we don't want shadows cast at critical times of the year on the memorial and on the street. We don't intend to simply build buildings that are by themselves, as we had before, and as we have in other cities, Singapore, Chicago, wherever. We want buildings that relate to a new neighborhood. That requires a coordination; it's not just about building the highest building, but how does that building act on the street, what happens on the base?

And I have to say I did not win all my battles. Just south of the Freedom Tower I proposed Hero's Park, which I though was an important part between the memorial itself and the placing of tower. Because the tower is much bigger in its base, I lost the park. It was a loss, I admit. I couldn't win it. I tried my best. I was fortunate to be able to gain a park space south of Liberty Street.

I just want to say that this process is dependent on public participation, dependent on people voicing their opinions, voicing their likes and dislikes, bringing in new ideas, I believe that with such pressure on the project, it is only the public that could steer it in a way that it is enlightened. Because this is under pressure and why shouldn't it be-- life is always under pressure.

Lopate: Part of that 1776-foot tower will be a broadcast antenna won't it? Most people did not like the old World Trade Center towers, and then they stuck that thing on top of it so one of them had a spike on top of it all. That even ruined the design even a bit more. This will be integrated into it?

Libeskind: The designs that the public saw, which I stood by, which are presented by the governor, and the mayor, and by Skidmore, Owings, and Merrill, and the developer, mark the skyline in a meaningful way. Again it's not a 150 story office building. It's a 65 story tower, with five stories of public programs, and antennae that reach all the way to 1776 feet; there are the ecological windmills in between. And I thought it was a very interesting and very successful tower, albeit a tower that is molded from many different angles.

I actually disagree with Paul Goldberger who said that the tower, because it was designed by these forces he said somewhere that it looked like a camel designed by the committee. First of all the camel wasn't designed by committee but by God, and there is nothing wrong with a camel because they have to go into the desert.

(laughter)

Lopate: But you should recognize that Paul Goldberger was trying to come to your defense when he made that statement. We have run out of time but I really want to give each of you a chance to say anything that you feel you wanted to say if you wanted to say something, and I was stupid enough not ask you the right question to elicit that statement. So is there anything else you wanted to add Santiago?

Calatrava: No, just to say that I am very thankful again for the opportunity to have spoken here, and that this one year of work have been an unbelievable experience. Seeing, as I said before, my client, the Port Authority, my partners and everybody working together under this high profile and still deliver the very best we could.

Lopate: Michael?

Arad: I just wanted to thank you, and thank you all for coming here.

Libeskind: It's great to work with great people. And again I just encourage everyone, not just New Yorkers, but anyone who cares about the development of Ground Zero, and who doesn't, to be part of it. I truly encourage it. Because it is only the public enlightened process that will make this site into something that will not just be sad, or business as usual, which is so often the case.

Lopate: And I want to say thanks to Rick Bell and the people involved here. When they gave me the opportunity, I jumped at it because the prospect of talking with three such amazing designers, creators, was very exciting for me. Thanks so much for participating and thank you all for coming.

Â

Opportunity Zones: An Empty OZ

You may have missed it, but tucked discreetly into President George W. Bush's acceptance speech at the Republican Convention was a freshly minted community development proposal to strengthen local distressed economies throughout the country. Upon Bush announcing the creation of "Opportunity Zones" in his September 2nd address, the White House subsequently revealed in a two page press releasethat 40 urban and rural areas would soon be eligible for a range of tax incentives for small businesses and be "moved to the front of the line for certain assistance programs". The stated goals of these zones are "to assist America's transitioning neighborhoods" and extend "economic prosperity‚to every corner of our country".

For New Yorkers, this talk of stimulating economic development in designated urban "zones" might sound familiar. "Enterprise" Zones were originally introduced to the American scene in the late 1970's by former New York State congressmen Jack Kemp and Robert Garcia. Kemp, who was later named head of the U.S Department of Housing and Urban Development (HUD) in the 1980's, tried unsuccessfully to launch Enterprise Zones under the George H.W. Bush administration. But it wasn't until Bill Clinton took office and Harlem Congressman Charlie Rangel championed the cause that the idea of using tax incentives as catalysts for private investment in poor neighborhoods was fully realized - and significantly expanded - in the form of the newly fashioned "Empowerment" Zone (EZ).

Rangel ensured that New York City, specifically Harlem, Inwood, Washington Heights and the South Bronx, would be included in America's first round of EZ funding in 1994. As a result, Upper Manhattan and the South Bronx received $250 million in Federal tax credits and $100 million in Federal funding for commercial development, job creation, social services, health care and cultural development. This investment pool was matched by an additional $200 million in total commitments from New York City and State.

At that time a total of 72 urban areas and 33 rural areas nationwide were named Empowerment Zones or Enterprise Communities (which cover smaller or less-densely populated areas) and received a total of $1.5 billion in performance grants and more than $2.5 billion in tax incentives. The Taxpayer Relief Act of 1997 authorized a second round of EZ designations and in 1999 an additional 15 distressed urban communities and 5 rural areas became eligible for an additional $3.8 billion in federal grants and tax-exempt bonding authority.

High Hopes, Few Details

Given this legacy, the Opportunity Zone (or "OZ", in the spirit of HUD shorthand) seemed to promise a credible federal effort to spur job growth through small business development. More importantly, the commitment to the OZ program seemed to reinforce the "Ownership Society" Bush so frequently invokes.

Although quite light-handed in its own promotion of the OZ program, the Bush Administration has certainly encouraged high expectations. As with any big ticket government program, OZ aspirants will have to run a bureaucratic gauntlet by submitting an application and a plan "which sets concrete, measurable goals for reducing local regulatory and tax barriers to construction, residential development and business creation." Of course, if approved as an OZ, considerable reporting will be required by the organization representing the designated area.

Once selected, an OZ community would presumably become a veritable hothouse of enterprise and social development. According to the White House press statement, an OZ represents a "comprehensive, results-based approach, expanding the focus of assistance beyond economic activity to encompass education, job training, affordable housing, and other activities critical for a vibrant community." A HUD official described Opportunity Zones as a holistic, inter-agency effort which would involve, in addition to HUD, the Department of Labor, the Treasury Department, the Small Business Administration, the Commerce Department, the Department of Education and potentially other federal agencies.

But perhaps the greatest enthusiasm was expressed by the Zone granddaddy himself, Jack Kemp, when he wrote effusively of how he saw the OZ's place in history. When bundled with Bush's proposed Social Security reform and tax reform, Kemp declared, Opportunity Zones represent "perhaps the boldest domestic policy vision since FDR's ‘New Deal' or LBJ's ‘Great Society'." "[B}ut unlike FDR and LBJ", Kemp continued, "Bush's vision is consistent with individual liberty, free markets and entrepreneurial capitalism."

Given the fact that Opportunity Zones were offered up barely 60 days before the election, maybe it's unfair to take such flourishes too seriously. But, for the record, let's just say that if you peek behind the curtain of the great and wonderful OZ, you may find the view less than breath-taking.

First of all, it's hard to find details on the Opportunity Zone, a supposedly historic presidential initiative that has somehow managed to fly far below many a radar screen. An official I spoke to at HUD, the agency that would most likely coordinate the administration of the OZ program, confessed that he hadn't actually heard the phrase Opportunity Zone until it left the President's lips on national TV. All he knew was what was already outlined in the press release.

When I pressed another HUD spokesman for more information – proposed costs, timetable, additional literature, etc. - he affirmed, with no detectable sense of irony, that "the devil is in the details" and suggested I call the White House advisory body, the Domestic Policy Council. My phone calls to the White House did not yield any more information, not even a proposed rough dollar amount of the program, much less a person willing to go on the record about it.

Community Inspiration

Ken Knuckles, the President and CEO of the largest and arguably most successful EZ in the country, the Upper Manhattan Empowerment Zone, was wholly unfamiliar with the OZ until I shared the press release with him. Logic dictates that Knuckles would be an interested party, since one of the two ways a community can qualify to be an Opportunity Zone is by already having designation as an Empowerment Zone, Enterprise Community or Renewal Community (a second tier zone created by the Bush administration).

The other way for an area to qualify as an OZ is by receiving a newly proposed, largely yet undefined, designation as a "community in transition". This is described only as an area that has "suffered from a significant decline in the economic base, including a decline in manufacturing and retail establishments", and is "transitioning to a ‚21st century economy."

"Upper Manhattan was not the inspiration" for Opportunity Zones, Knuckles concluded after reading the OZ release. In fact, as Bush criss-crosses the country on the campaign trail, offering to deliver an OZ to a neighborhood near you, he is unabashedly and explicitly seeking to woo swing state voters still seething over the alleged export of American manufacturing jobs oversees. While conspicuously short on other details, the release goes as far as listing examples of communities that might qualify for Opportunity Zone designation, including election battleground territories like "Cuyahoga County, Ohio" and "Erie County, Pennsylvania".

Community Development Record

Knuckles harbors serious doubts that OZ's could ever prove to be effective in densely populated, non manufacturing-dependent, areas like New York, in large part because tax incentives are offered by Opportunity Zones to the exclusion of any other economic development tool or stimuli . This is a signature feature of the Bush administration; the Empowerment Zones introduced by the Bush Administration in a third round authorization in 2002 were stripped of all federal grants, investment dollars and leveraging opportunities originally provided under the Clinton administration, leaving tax incentives alone to do the job of "empowerment".

Knuckles expressed no interest in relinquishing Upper Manhattan's hard-fought-for EZ status, a consequence, apparently, if Upper Manhattan or any EZ were to, for some reason, seek OZ designation. In his opinion, this would represent a trading down. "Low-interest, patient capital", which is something the first round of Empowerment Zones were set up to provide, is what is needed in Harlem, Knuckles insisted, "over and beyond tax incentives".

Dawn Rivers Baker, who, as Editor-in-Chief of the MicroEnterprise Journal, tracks and comments on federal policy as it relates to the micro- and small business community, dismisses the OZ proposal as an empty campaign gesture. She maintains the Bush administration has consistently tried to dismantle small business support mechanisms that have traditionally been provided by the federal government.

To illustrate her point Baker compiled a laundry list of small business programs the Bush administration has tried to cut or eliminate by budgetary means since January 2001, including the New Markets program for low-income entrepreneurs, the Small Business Development Center program and the Small Business Administrationitself. If not for the intervention of Congress, Baker insists, these programs and others like it would have been gutted. Other critics point to the fact that the Bush Administration has attempted to weaken a wide range of community development programs and safeguards like the Section 8 subsidized housing program, the Community Development Financial Institution program and the Community Reinvestment Act. Bush even cut the Empowerment Zone from his 2004 budget, only to have it restored, again, by Congress.

This is especially unsettling considering that the OZ model seems to be lifted directly from the tax relief section of the EZ playbook. Opportunity Zones do include some added perks, like lower income tax rates for businesses and the ability for businesses to "expense" an additional $100,000 for the purchase of tools and equipment under new tax policies. But, according to Michael Barr, who as a Treasury Department official from 1995 to 2001 helped design and implement Empowerment Zones, all the other OZ features – investment incentives, priority designation when applying for existing Federal programs; incentives to hire new workers; regulatory relief – already exist under the Empowerment Zone program.

"It's quite disappointing", Barr lamented. "What you have here is a lot of hype without substance or content; right now it looks like there's a lot of work for communities to go through [to receive OZ designation], without a whole lot of added benefit."

The Governors Island Plan: Last Chance to Get It Right?

I was tipped off to a major public meeting to chart the future of Governors Island that was being held in the middle of the summer.

Not surprisingly, given the timing, no more than a couple of hundred people wound up hearing preliminary ideas from the team of consultants working on the plan for the island. Still, the discussion was lively and there were lots of great ideas. And a number of speakers echoed the gnawing questions from my inner Brooklyn self about whether the planning process would serve the diverse populations of this city of eight million people.

Can The City Plan an Island?

This could be the city's last chance to get planning right for a major chunk of city land accessible to the entire metropolitan region. When the five boroughs were consolidated in 1898 only a small portion of Manhattan was densely developed. It was an historic opportunity to plan the future metropolis. It didn't happen. Instead the city let developers do pretty much what they wanted. Zoning outside of lower Manhattan was fairly liberal. Developers even took the lead in planning the subway lines, the main determinant of new growth. The result is a concrete and asphalt city with one of the lowest ratios of open space per person in the country. The last island that the city planned, Roosevelt Island, turned out to be another dense cluster that mimicked the overdeveloped East Side of Manhattan, albeit with greater sensitivity to good design. The city also missed the opportunity to plan for Staten Island, which got eaten up by unplanned sprawl after the South Richmond Plan was rejected in the 1970s.

The United States Coast Guard moved out of the 172-acre Governors Island in 1997 and last year it was turned over to the City and State of New York. It soon became clear that it was going to be hard to get the public investment required to turn it into another apartment complex like Roosevelt Island, nor the political support needed to give it to hotel and casino operators. So the federal, state and local governments agreed to deed restrictions that required it be redeveloped for recreation, education and limited commercial activities. At least forty acres must be for parks, at least 20 acres for educational uses, and 30 acres for "public benefit uses." That leaves over one-third of the land above water for other, possibly commercial, uses.

The body in charge of planning is the Governors Island Preservation and Education Corporation(GIPEC), a subsidiary of the Empire State Development Corporation. GIPEC's board is appointed by the Mayor and Governor.

A Model Island?

Governors Island may actually fill in some of the city's missing green space. We can all breathe a little easier knowing that one of the basic principles for planning the island is that it will be virtually car-free. Actually the island can be a giant demonstration project, an environmental oasis in a city with an epidemic of asthma and respiratory diseases and a horrible record of non-compliance with federal clean air regulations. It could have the city's best network of bicycle and pedestrian paths, with stunning views from waterfront promenades. At the planning meeting there seemed to be widespread approval of a car-free island, but some people also wanted to see it become a regional hub for maritime activity, which could conflict with the vision of the island as a bucolic paradise.

A seed planted by the planning consultants was the idea that the island could become a model of environmental and economic sustainability. Concretely, this could mean that it would produce its own energy and food for consumption in restaurants and dining rooms. And waste could be reduced, recycled and composted instead of being exported as it is in the rest of the city. This could be a "zero waste" island.

The consultants didn't go this far, but clearly Governors Island could become a model in many ways for the city's neighborhoods, generating valuable lessons in environmental management and sustainability. Without a permanent residential population, however, it would never match the conditions of most neighborhoods.

Enclave for the Elite?

But at the July meeting, many of the invited guests were troubled by the possibility that Governors Island would become an exclusive enclave. Indeed, this was probably the main question on everyone's mind. "We want to make sure this is not just an elite island," affirmed one speaker. Aside from worrying that those present at the meeting didn't reflect the full diversity of the city's neighborhoods, people were concerned that the "limited" commercial development being talked about -- the consultants mentioned an executive conference center, restaurants, a boutique hotel, a spa -- could chase away island visitors without deep pockets.

Some people worried how accessible the open space would be. Will the island have recreational facilities for everyone or only those who belong to organized teams? Will people with big families have places to romp, picnic and barbecue, or will it be a pristine place only for the genteel class or Manhattan's singles scene? One person cautioned that public access to the island's waterfront wasn't enough. "You can have public access in a private enclave, like Battery Park City," where the waterfront is technically open to the public but is designed in such a way that it's not inviting to the broader public.

Which gets us to Brooklyn. According to Craig Hammerman, the district manager of Community Board 6 in Brooklyn (the man who had tipped me off to the meeting), "Brooklyn seems to have been an afterthought." Through an accident of history, Governors Island wound up under the jurisdiction of Manhattan and belongs to Manhattan's Community Board One. Yet it's actually closer to Brooklyn than Manhattan. His community board asked the mayor to take a look at the community board boundaries, but to no avail. "The planning process appears to have been already determined," says Hammerman. Indeed, boutique hotels, pristine promenades and nature preserves may remake Governors Island in the image of Battery Park and leave no room for the people of Red Hook and Sunset Park. The next planning meeting will be scheduled for this fall. It should be in Brooklyn, there should be more outreach to neighborhoods, and it shouldn't be held when few New Yorkers are around.

Tom Angotti is Professor of Urban Affairs and Planning at Hunter College, City University of NY, editor of Progressive Planning Magazine, and a member of the Task Force on Community-based Planning.

Helping Pay The Rent: Section 8 Saved; Emergency Rent Coalition Created

With the lack of affordable housing a seemingly permanent crisis (See "Affordable Housing 2004"), paying the rent seems to be getting more difficult for more and more people. Of some 370,000 cases filed in Housing Court in 2003, roughly 90 percent were against tenants for non-payment of the rent. Last month, an annual survey completed by the United States Census Bureau revealed what few doubt: More people are spending more of their income on rent. The percentage of New Yorkers spending more than 35 percent of their income on rent rose, the survey found, from 38 percent to 42.5 percent.

There are two main avenues of help for those unable to pay their rent: ongoing help from government sources and emergency help from government sources and private sources, like charities and religious institutions. The Section 8 government subsidy for the chronically poor is the most important source of help people can get paying the rent that continues based on their need. A coalition of charitable agencies that helps individuals in an emergency situation is increasingly becoming an important source of assistance, filling in, more or less, for the government. There have been recent developments in both.

SECTION 8 SAVED

The city's main weapon to fight homelessness and make housing affordable - the federal rent subsidy known as Section 8 - was saved at the end of August when the U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development restored about $55 million in the program's funding for New York City, in response to an appeal by the New York City Housing Authority. Originally, HUD had proposed cutting $125 million.

But Section 8, whose share of HUD's budget has increased by 27 percent over the last three years, will still face significant cuts next year, advocates fear, particularly if President George W. Bush is reelected.

A housing authority spokesperson said if the agency faces a shortfall due to cuts, it will not cut the subsidy payments it makes to landlords nor ask tenants to pay more but instead look for savings in administration of the program.

Section 8 subsidies help pay the rent on apartments for 220,000 people in New York City. Any new vouchers are reserved for those facing serious housing emergencies: homeless families, victims of domestic violence, children in the care of the Administration of Child Services and intimidated witnesses to crimes.

Hundreds of thousands more people not in these categories technically qualify to receive Section 8 but are unlikely to get it - the waiting list has been closed for almost a decade. The assistance comes in two forms: 1. vouchers allow individuals to pay just 30 percent of their income to a private landlord, the landlord being paid the difference by the subsidy program. 2. Individuals can also reside in Section 8 housing projects.

As I have written before ("Section 8 and the Single Landlord") many of the nearly 30,000 private landlords who participate in Section 8 in the city are opting out of the program because, they say, it imposes too many rules and does not pay the rent in a timely fashion.

EMERGENCY RENT COALITION

Later this month, a new non-profit organization, the Emergency Rent Coalition, will elect its first board of directors. It is a group of about 20 agencies that separately offer a critical service to New Yorkers on a daily basis - rent arrears assistance. But by all accounts they never come close to meeting the need.

"We just felt there was such a need to come together to talk about some of the issues and concerns and try to create a system that worked," recalled Judy Milone, a co-founder of the coalition and assistant director of client services at the Federation of Protestant Welfare Agencies. "The need is so great."

The Emergency Rent Coalition started about four years ago with little more than a dozen people from various agencies trying to establish order in providing rental arrears assistance, a subcategory of the chaotic world of financial help available in New York City. It includes major charities like Catholic Charities and the Metropolitan Council on Jewish Poverty and smaller outfits like Lenox Hill Neighborhood House.

No one can say exactly how much money goes to help people pay their rent or how many people actually get help. But advocates conservatively estimate that tens of thousands of New Yorkers get help that adds up to tens of millions of dollars every year.

The assistance can come from a variety of sources, public and private. The city uses federal, state and city money to provide assistance through grants and loans to people facing a housing emergency. Charities, religious institutions and community-based organizations of all stripes use federal and private money to provide similar emergency assistance.