That New York City has extreme wealth and extreme poverty, and lots of both, seems like a law of nature, older than the subway or the Brooklyn Bridge. While there is a lot of truth in that, the city has not always had the extremes to the extent it has them now. Today, the wealthiest 1 percent of city residents has 44 percent of all income in the city, a share nearly four times as great as 30 years ago.

Over the past three decades, the bulk of economic gains in the United States and New York has accrued to those at the very top of the income pyramid. The economy has grown significantly over this period, but those at the very top have taken a vastly disproportionate share of the gains, leaving very little for the rest.

The Big Change

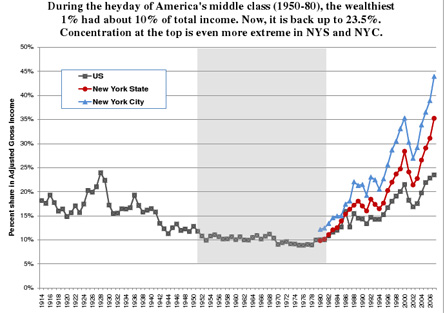

The chart below, from a recent report on income concentration by the Fiscal Policy Institute, demonstrates that the first three decades after World War II -- from the mid 1940s to the late 1970s -- were a time when the share of total income going to the wealthiest 1 percent stayed remarkably steady. In 1947, the top 1 percent received 12 percent of the total, and three decades later, in 1978, that remained about the same -- actually slightly lower -- at 9 percent. The top 1 percent's share held at close to 10 percent throughout all three decades.

The post-war era is widely seen as a golden age of the middle class, with an economy fueled in significant part by middle-class spending. The middle class flourished. Its numbers expanded, and its living standards rose steadily. The U.S. economy grew, and that growth lifted millions of families out of poverty and into the middle class. Parents could expect their children to do even better than they had done.

The top 1 percent gained as well -- executives and bankers enjoyed the success of the American economy as much as anyone. Their incomes grew steadily, but together with the rest of the country in a rising tide that lifted all boats, in New York and in the country as a whole. We grew together.

The picture since 1980 has changed dramatically . In 1980, the top 1 percent of households nationally held 10 percent of the total income. By 2007, that share had more than doubled, rising to 23.5 percent -- a high previously attained only in 1928, the eve of the 1929 stock market crash that ushered in the Great Depression.

The economy has grown considerably in the three decades since 1980, albeit not as fast as in the 1950s through the 1970s. But growth after 1980 looked different than it had in the preceding era. The incomes of the top 1 percent and the top 5 percent grew faster, much faster, than in the post-war period, while the incomes of everyone else, those with low incomes as well as the broad middle class, faltered and stagnated. We grew apart.

Growing Apart in New York

In New York City in 1980, the share of all incomes going to the top 1 percent was 12 percent -- more or less in line with the rest of the U.S. But by 1990 the top 1 percent's share in New York City had risen to almost 20 percent, and after a period of extreme concentration in the late 1990s reached nearly 35 percent in 2000. The 2001-2003 recession briefly pushed the top share down, but then it gained at its fastest pace over the past 30 years, climbing to 44 percent in 2007, almost double the historically high national level of 23.5 percent.

New York State is the most polarized among the 50 states, and New York City is the most polarized among the 25 largest cities in the United States.

Today, most experts expect the pace of the nascent recovery from the Great Recession of 2008-09 to remain subdued in large part because of high household debt burdens, stagnant or declining wages, and a bleak job outlook. The recession was triggered by the bursting of the housing bubble and a speculative, excess-prone financial system, but it occurred in an economy with an increasingly shaky foundation characterized by weak job growth, continued export of middle-income jobs and wage growth that failed to keep pace with inflation and the growth in the productivity of labor.

This shaky foundation has a lot to do with the post-1980 hyper-concentration of income. The expansion from 2004 to 2007 was the first in which family incomes and median wages adjusted for inflation did not rise over the cycle to reach the peak of the previous business cycle. Despite economic growth, many Americans never saw their income return to the levels they had reached in 2000. Faced with this, families turned to debt, using credit cards and home equity borrowing to sustain their living standards. The crash of the financial and housing bubbles destroyed trillions of dollars in retirement and college savings that had been accumulated by middle- and low-income Americans, and decimated the value of their homes.

Rebuilding that wealth and economic security and restoring a sense of optimism for the next generation will be doubly difficult given the current polarized system of economic rewards and the bleak outlook for job and economic growth. The broadly shared prosperity that prevailed in the three decades after World War II is a distant memory. Are we destined to grow further apart?

Growth at the Top

The concentration of income growth at the top does not necessarily mean that those below the top will not see living standards improve. Incomes could rise up and down the income scale even as gains are disproportionately concentrated at the top. That, though, is not what has happened recently.

Over the period from 1980 to 2007, when inflation-adjusted income in New York state grew an average of 2.1 percent a year after adjusting for population increase, incomes for those in the bottom half of the income spectrum (incomes below $33,000) generally declined. Incomes of people in the middle-range (incomes from $33,000 to $176,000) rose but at only a fraction of the pace of total income growth. Meanwhile, the real incomes of those in the top 1 percent (incomes over $580,000) grew 7 percent annually, over three times as fast as overall income growth. The rest of those in the top 5 percent (incomes from $176,000 to $580,000) saw their incomes rise a little faster than the pace of total income growth.

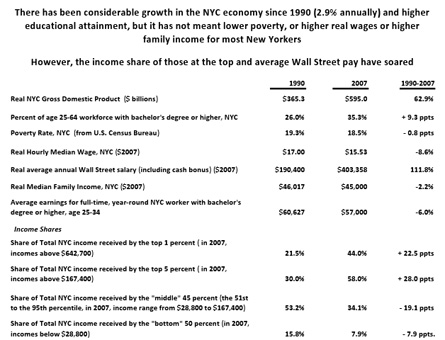

Most New York City workers and their families have experienced very little real income or wage growth over the past two decades. For example, as the table below shows, the inflation-adjusted median hourly wage fell by 8.6 percent from 1990 to 2007, and poverty came down very little during a period when the income share of the top 1 percent doubled from 21.5 percent to 44 percent.

New York's Stark Split

In New York City, there are about 34,500 households, representing about 90,000 people, in the top 1 percent. On average, these households have annual incomes of $3.7 million. At the same time, about 900,000 people in New York City -- about 10.5 percent of city residents -- live in deep poverty. Deep poverty is half of the federal poverty line; for a four-person family, that means an income of $10,500. An annual income of $3.7 million translates into a daily level of $10,137 -- more than the average annual family income of those living in deep poverty. According to state tax data, half of the households in New York City have annual incomes below $30,000, an amount that the top 1 percent receives over the course of a holiday weekend.

If New York City were a nation, its level of income concentration would rank 15th worst among 134 countries, between Chile and Honduras. Wall Street, with its stratospheric profits and bonuses, sits within 15 miles of the Bronx -- the nation's poorest urban county.

Behind the Income Concentration

It is often argued that skills-based technological change largely explains the trend toward greater income polarization. According to this reasoning, the steady advance of technological change raises skill requirements. As a result, those who pursue higher education and obtain the skills needed to master new technologies receive greater economic rewards. Those lacking higher education see the demand slacken for their limited skills and their wages fall accordingly.

There is a certain appeal to this explanation, but it does not account for the intensified degree of income concentration that has taken place. One third of New Yorkers aged 25 to 64 in the workforce now have a four-year college degree or better, a considerable increase since 1990. Despite that, income gains have been concentrated among a much smaller segment of the population. In New York City, inflation-adjusted annual earnings of college-educated young workers have fallen 6 percent from 1990 levels. In addition, among the well-educated those with the highest incomes do not have the best education.

Something else must be at work since education, however important on an individual level, simply cannot serve as a compelling explanation for increased income concentration.

Moreover, skills-based technological change -- and globalization for that matter -- has occurred throughout the developed world. Yet no other country has seen the heightened polarization of incomes that has taken place in the United States. In the early 1970s, the richest 1 percent in the U.S. had a share of total income that was roughly in line with several other developed economies, including Canada, France, Japan and the United Kingdom. By 2000, however, the top 1 percent's share had risen much higher in the U.S. than in any other country. In Germany, there was almost no change in the income share of the top 1 percent. France even saw a decline in the share going to the richest 1 percent, and by 2000 that share was half what it was in the United States. Japan’s top 1 percent received a slight gain in share, but that share also was only half that of the U.S. in 2000.

Jacob Hacker and Paul Pierson persuasively argue in their book, Winner-Take-All Politics, that incomes have risen so high at the top not because of education or other economic factors but because of national policy changes that have favored the wealthy and certain institutions, such as the largest financial companies. Hacker and Pierson point to several national policy changes involving labor markets and labor unions, financial deregulation and taxation that were largely unique to the U.S.

These changes -- such as financial deregulation and the failure to limit executive compensation -- have tremendously benefited large financial firms and corporate executives. Those developments have made a big difference in New York City. National policies that allowed the purchasing power of the minimum wage to seriously erode and that reduced the power of labor unions also have made a significant difference in depressing wages for middle- and low-income workers.

There is nothing inevitable in the operation of markets that generates extreme polarization in the distribution of economic rewards, but policy choices on how markets can operate and on taxes have everything to do with the distribution of economic rewards.

It has become increasingly understood that the many steps taken since the 1970s to deregulate financial markets played a key role in excessive speculation, poorly designed and unregulated financial innovations, and eventually, in the 2008 financial collapse. Deregulation gave financial institutions virtually a free hand to combine commercial and investment-banking, increase leverage and sell exotic financial instruments such as derivatives without regard for effective risk management. In financial bubble periods, such as the one based on commercial real estate lending in the 1980s and the dot.com boom of the late 1990s, financial firms reap enormous profits and pay their top bankers and traders huge bonuses. Nationally, in 2004, Hacker and Pierson point out, nearly 20 percent of America's super-wealthy (the top one-tenth of 1 percent) worked in finance; 40 percent were CEOs and other executives.

Federal tax policy also has contributed greatly . The moves to reduce top tax rates and capital gains tax rates -- as Presidents Ronald Reagan and George W. Bush did -- and to maintain glaring loopholes have all had a major effect. Hacker and Pierson found that the average effective federal income tax rate on the top 1 percent fell by one third from 1970 to 2004.

States have much more limited authority. Despite that, several tax policy changes enacted by New York State have eased the tax burden at the top. New Yorks top state personal income tax rate was 15 percent in the early 1970s and in several steps it was reduced to 6.85 percent by 2009, when the state enacted a temporary surcharge. While the management fees referred to as "carried interest" received by hedge fund managers is taxed at the lower capital gains tax rate at the federal level, New York City exempts it from taxation altogether under the city's unincorporated business tax.

Can We Grow Together?

The Great Recession dramatically worsened an already highly polarized economy. Policy changes are needed at the state and national level to stimulate more robust growth and to reverse excessive income polarization. Not all of these changes are politically possible in the immediate term, but it is hard to see how the economy can fundamentally improve in the absence of significant changes that move us toward more broadly shared prosperity.

The kinds of policies that would help include: increasing the minimum wage, strengthening the enforcement of labor standards, expanding living wage requirements, increasing labor union membership, making investments in economic growth rather than slashing government budgets, helping small businesses grow, provide real assistance on home foreclosures including keeping people in their homes as renters, and investing in public higher education.

At this moment, the most critical move to reverse extreme income polarization would be enacting progressive tax policies at all levels of government. In New York State, the top 1 percent pays a smaller share of their income in state and local taxes than all of those less well off, from the upper-middle, to the middle, to the poor. The story is similar in New York City. While the top one percent has 44 percent of city income and pay slightly over half of all local personal income taxes, they account for only one-third of total New York City tax revenue including personal income, city sales and residential property taxes.

At the national level, the income and estate tax changes agreed to by President Barack Obama and the Republican leadership will give 34 percent of the tax cuts going to all New Yorkers to the richest 1 percent. On average, the richest households will receive a tax cut averaging $124,000 in 2011. The middle fifth of New Yorkers will average a $1,500 tax cut, and the poorest 20 percent will get less than $300 on average.

There are many reasons to be concerned about New York's extreme income concentration. Among the most pressing is that the pronounced polarization in the distribution of the rewards of economic growth is holding back the nascent recovery. Growth is stalled because our system of rewarding economic effort is out of kilter. In the last three decades, the U.S. has become a country where average workers can no longer count on being paid for their productivity, while those at the top receive an income far out of proportion to what they contribute to our economy.

James Parrott is deputy director and chief economist of the Fiscal Policy Institute. He has been studying and writing about the New York economy since he landed in New York City a quarter century ago.