Campaign finance regulation is about to battle with the First Amendment.

The city Campaign Finance Board is gearing up to outline a proposal to regulate the disclosure of independent campaign spending. For the first time, spending by unions, corporations or individuals to advocate for or against a candidate will be regulated and overseen by the city Campaign Finance Board. The proposal, initially drafted by the City Charter Revision Commission last year, was approved by more than 80 percent of voters.

There will be no limit on how much an entity can spend, but every dollar -- from money spent on mailers to funding for volunteers to knock on your door -- will have to be accounted for.

As internal conversations at the Campaign Finance Board are put down on paper in preparation for a public hearing on March 10, many in the campaign business would like to keep the accounts under wraps.

The city's unions are already preparing to defend their member-to-member communication as protected under the First Amendment and therefore exempt from disclosure.

“Make no mistake: communication between a union and its members is not an independent expenditure. It is a constitutionally protected free speech issue,” said Stuart Appelbaum, president of the Retail, Wholesale and Department Store Union, in a prepared statement.

The battle over what exactly is an independent expenditure will not stop there.

What to Consider

The U.S. Supreme Court, in its 2010 Citizens United decision, struck down a ban on independent corporate election spending, arguing a robocall or a mailer is protected under the First Amendment's right to free speech.

Before that, the city had seen an uptick in money spent on candidates without their approval. During the 2009 campaign, the Independence Party, financially backed by real estate interests, faced off in several districts with the Working Families Party, which had the support of many labor unions. Both spent their own money on their favorite candidates.

In the board's report on the 2009 election, it called this third party participation "unprecedented."

In New York City, the board argues, the disclosure of independent expenditures is particularly important because most candidates participate in the public campaign finance system. They receive public dollars and abide by spending limits -- from $161,000 for a primary City Council race to about $6.2 million for a primary mayor race. If third parties spend on behalf of candidates, it can tip the scale.

To limit that influence, the board is set to consider a menu of options. For instance, it will determine whether an independent expenditure has to expressly advocate for or against the candidate with certain phrases (such as "Vote for") or if merely mentioning the candidate is enough to trigger disclosure, according to a memo on the options.

The board will determine what a third party entity will have to disclose about itself, such as where it gets its funding. It is contemplating whether to force third parties to identify themselves on their literature or television ads and how often these parties will have to report to the board.

It is also considering whether to exempt certain support of candidates, such as newspaper editorials.

Keeping Labor Out

To labor leaders, these exemptions are key.

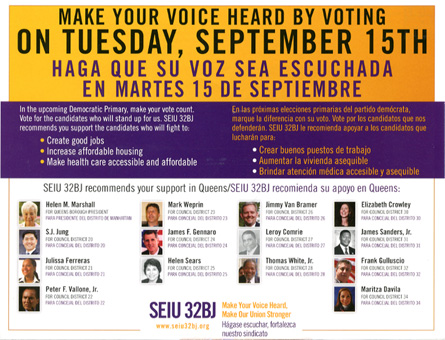

According to several city unions, the disclosure requirement should not cover communication meant only for their members. This could include a monthly newsletter announcing an endorsement or -- potentially -- a mailer urging its members to vote for a candidate.

“We would be happy to comply with disclosure requirements for independent expenditures on the city level," said Kevin Finnegan, the political director of 1199 SEIU United Healthcare Workers East, in a prepared statement. "We already report all political spending on communications to the general public on our NY state and federal filings. New York and federal reporting requirements do not require any reporting of communications with our own members. It is generally assumed that labor unions and other membership organizations have an absolute right to communicate with their own members regarding political or legislative issues and cannot be regulated or discouraged under the First Amendment. We have a continuing concern that staff at the NYC Campaign Finance Board believes that they are not subject to constitutional restrictions and may attempt to restrict or discourage the exercise of protected speech.”

In the opinion of some election attorneys, the union's First Amendment argument would hold up in court.

"Courts have ruled the unions have a First Amendment right to communicate with their members and such communications do not constitute regulative or political activity," said Henry Berger, an election lawyer. "I think that's totally protected and the CFB has absolutely no jurisdiction over that."

Others see arguments for including such communication. Some unions in the city have as many as 125,000 members. If a mailer goes out to them, said Gene Russianoff of the New York Public Interest Research Group, it could turn the tide for or against a candidate.

"We're talking about disclosure here. We're not talking about prohibition," said Russianoff. "On the one hand, there might be First Amendment concerns. On the other hand, contacting a union with hundreds of thousands of members is a potent independent expenditure."

How It's Done Elsewhere

The board is looking to other cities and states as an example.

In Los Angeles, third parties are required to disclose both independent expenditures and any communication with its membership. They are put in separate categories.

It is unclear what model the Campaign Finance Board will adopt in the five boroughs. Following its first public hearing on March 10, the board will draft rules and hold an additional public hearing for feedback. It would then put the rules before the full board for a vote.

It hopes to have rules set in place for a City Council special election this fall.

"Because this is an entirely new area for us we want to make it as public a process as possible," said Eric Friedman of the Campaign Finance Board. "There is ultimately this menu of options, from narrow to broad. There are good arguments to make it as broad as possible. There are good arguments to go the other way."