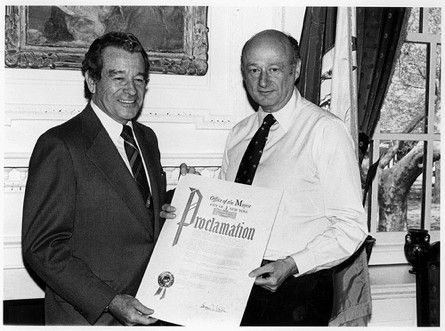

Mayor Ed Koch at City Hall, date unknown. Photo from Flickr, courtesy Kheel Center, Cornell University.

Editor's Note: A previous version of this story incorrectly referred to the findings of a draft report based on data from the New York Independent System Operator.

NEW YORK – For former Mayor Ed Koch, the turning point in his thinking about nuclear power came in March 2011 after the radioactive cataclysm in Japan caused by a crushing tsunami.

“It was incredible how the Japanese government changed its warnings from day to day,” Koch said of the response to the multiple meltdowns at the Fukushima Daiichi plant that became the worst nuclear disaster since the 1986 explosion at Chernobyl.

“It was clear to me that the owners of the facility were lying. The Japanese government lied at times as well. I thought to myself, what's the sense of all of this? When I put all that together I said, the hell with it. I said, why are we tempting fate? Germany will eliminate all nuclear power, and that's what we should do,” Koch told the Gotham Gazette in a recent interview.

Koch has joined a growing chorus of environmental advocates and politicians calling for Indian Point Energy Center in Westchester County to be shut down, saying the aging nuclear plant poses a danger to the 8 million people who live 24 miles to the south in New York City – especially in the wake of what was learned from the Fukushima disaster.

“We know there is no possibility of evacuating New York City,” he said. “There is no evacuation plan.”

Koch said he had been aware of the problem when he was mayor, but did nothing about it. “I thought, â€It's not my problem. It's the governor's problem and the federal government's problem.’ I should have said it was my problem. I did nothing to address it at the time. I should have.”

Koch’s turnabout on nuclear power surprised some people, not the least of whom were officials at Entergy Corp., the owner of the Indian Point nuclear plant.

The company, which has applied to the U.S. Nuclear Regulatory Commission to extend its operating license for another 20 years, said it had approached Koch two years ago asking him to be pitchman for its coolant system. Koch confirmed that he had been approached by the company.

“I said if I were to do it, they would have to provide scientific opinions that the alternative method was acceptable scientifically and would do the job, to which they agreed,” Koch told the Gazette in an email.

“At that time, I was in support of the use of nuclear energy. Fukushima had not yet occurred. However, after thinking about the offer, I turned it down because I thought it would have an adverse impact on my pro bono efforts to get support for the campaign to have the legislature accept impartial redistricting,” he continued, referring to his fight for an independent redistricting commission. “When I called to say I wouldn’t do it, I was offered $150,000. I said no, I wouldn’t do it no matter what the pay.”

Entergy, through a spokesman, denied they offered him money, instead saying it was the former mayor who brought up the subject of payment. Both Entergy and Koch confirmed, however, that the former mayor ultimately declined to promote the facility.

In a June 13 column in The Huffington Post, written with Hudson Riverkeeper president Paul Gallay, Koch noted that one of Indian Point’s two reactors faces the highest risk of damage due to an earthquake of any nuclear facility in the U.S.

The claim was first reported in 2011 by MSNBC after an analysis of NRC data -- but was later disputed by the agency itself. "Nuclear power is a complicated, technical subject, and we naturally try to simplify it to make it understandable to the general public. Sometimes, however, simplification leads to misunderstanding, and misunderstanding causes fear," wrote NRC spokesman Eliot Brenner on the agency's website. The NRC, he said, does not rank nuclear plants according to seismic risk.

Koch and Gallay also cited a 2008 study by scientists at Columbia University’s Lamont-Doherty Earth Observatory that confirmed that Indian Point sits “astride the intersection” of two active seismic zones.

Koch and Gallay also point out in their article that the plant’s fire safety plan does not meet minimum federal standards.

Entergy disputes these claims. Indian Point spokesman Jim Steets said the analysis conducted by Lamont-Doherty “is not fact-based. They have expressed opinions. We are prepared to withstand an earthquake 100 times greater than what would have been experienced in the Indian Point area.”

But he also added: “There is some evidence that earthquakes (in the area) could be stronger. We are looking into that.”

Steets said the cooling system for the Daiichi plant’s reactors was damaged by the tsunami, not by the earthquake that preceded it. But the results of an independent investigation commissioned by the Japanese parliament say otherwise.

“A conclusion denying quake damage cannot be drawn,” said the report released last week. “The recorded seismic motion at Fukushima Daiichi exceeded the assumption of the new guideline. It is clear that appropriate anti-seismic reinforcements were not in place at the time of the March 11 earthquake.”

As for the plant’s fire plan, Steets replied: “The issue has been resolved to NRC’s satisfaction. A lot of the remedies have been completed; others are being engineered and resolved.”

But it is Entergy’s evacuation plan for the area around Indian Point, in the case of an accident, that particularly resonates with the former mayor. The company confirmed that the plant’s “emergency planning zone” encompasses the 10-mile area around Indian Point and makes no provision for New York City.

But Steets said the flooding that destroyed the Daiichi plant’s reactors was impossible at Indian Point’s location, and that the design of the plant negated the possibility of a massive explosion, such as the one at Chernobyl.

These factors would give the city time to mobilize in the event of an accident, he said. “An emergency that necessitated a massive evacuation would not occur instantaneously,” Steets said.

The city’s Office of Emergency Management has designed an “area evacuation plan” that could be used in the event of a nuclear accident, a spokeswoman said. The plan is currently designed to evacuate one neighborhood or swaths of the city in coordination with transit agencies.

But OEM spokeswoman Judith Kane said it could be used to evacuate the whole city “in theory,” though she said it was “hard to imagine” such a scenario. She said that in the case of a nuclear emergency, the city would likely rely on plume modeling to track the spread of radiation and make decisions.

The disaster in Fukushima, she said, encouraged the agency to coordinate more closely with its counterpart in Westchester County. “It's inevitable with any disaster,” she said. “When something happens in another part of the world, it always raises the question, what would happen in New York City? Is this good enough? Does it cover the worst case scenario?"

After the disaster in Fukushima, a 12-mile exclusion zone was established around the Daiichi plant and approximately 170,000 residents were evacuated. Persons living 12 to 24 miles from the plant were first asked to remain indoors, and then evacuations were initiated for these areas as well.

Koch said that if he were in the current mayor’s position he “would be putting the city’s experts together preparing a memo of opposition to the renewal application.”

Mayor Michael Bloomberg has spoken in favor of renewing Indian Point’s licenses, and has sharply rejected the idea of closing the plant.

“Well, if you closed Indian Point down today we’d have enormous blackouts. There is no alternative to the energy that we get from Indian Point. Four or five years from now that probably is not going to be true,” Bloomberg said in June 2011. “All types of power generation have risks and nuclear hasn’t killed anybody.”

In their article, Koch and Gallay said the New York metro area does not require Indian Point for its immediate power needs, arguing there is enough surplus power available to close the plant now and still meet regional demands through 2020.

A study commissioned by New York City confirmed that 2011 data from the New York Independent System Operator showed sufficient power through 2020.

But the final version of the report by Charles River Associates adjusted the ISO's forecast of 91 percent energy efficiency penetration – the degree to which energy efficiency targets have been met – saying that a 50 percent rate was more "realistic."

After adjusting the ISO data, the final report argued that the grid would fall short in the summer of 2016. Charles River Associates also raised questions about the reliability of power distribution without Indian Point. And their study estimates that the city's consumers would see their energy bills increase by 5 to 10 percent if Indian Point were to close.

A separate study, by Synapse Energy Economics, found that the cost increase to consumers might actually be far less, only 1 to 3 percent.

Koch said that when challenging a nuclear power plant “local governments feel powerless. The Congress has taken most of the power of local governments away and made it solely a function of a federal agency.”

A case in point is Vermont’s attempts to close Vermont Yankee, an Entergy plant situated on the Connecticut River, which have been unsuccessful to date. A challenge to Vermont Yankee’s license renewal failed last month in federal court.

Phillip Musegaas, director of Riverkeeper’s Hudson River Program, said that the debate about keeping Indian Point open boils down to one question: “If you don’t need the power, why take the risk? Its location is fundamentally problematic.”

When asked what he believed was the fundamental obstacle to closing Indian Point, Koch responded: “It’s called money. People invested billions in these plants … and are going to fight tooth-and-nail to protect these investments.”

NRC public hearings on Entergy’s application for renewal of Indian Point’s licenses are set to begin in October, though seismic risk and evacuation planning won’t be evaluated as part of the process. The reactors are currently licensed to operate until 2013 and 2015, respectively.