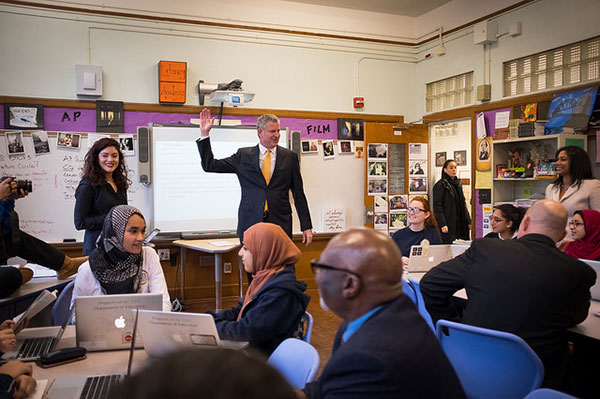

The Mayoral Control Debate We Should Be Having

(Credit: Edwin J. Torres/ Mayoral Photography Office)

The annual Rite of Bashage on mayoral control of city schools is upon us. This month, Senate Minority Leader John Flanagan will beat up on Mayor Bill de Blasio for all manner of supposed educational sins before caving to an inevitable extension of mayoral control. Having been soundly whipped by the senatorial wet noodle, de Blasio will walk away a winner.

But there is a real education issue this re-election year that the mayor should be pushed on: the matter of a Chancellor search. The public has a right to know which side of the de Blasio record they’ll be voting on.

In 2012, then-candidate de Blasio criticized the serial secret appointments of Joel Klein, Cathie Black, and Dennis Walcott by Mayor Michael Bloomberg. As reported by City & State at the time, de Blasio said, “Cathie Black was pushed down our throat because of mayoral control gone to an undemocratic level. We need a more democratic—small-d democratic—version of mayoral control, and we need a chancellor who is presented to the public, not just forced down our throat.”

A year later, after being elected, he back-tracked, asserting no such democratic process of public involvement was necessary. Chancellor Carmen Fariña was unilaterally appointed without a public search or vetting.

This election is the first time de Blasio’s flip-flopping can be evaluated by voters. More importantly, the manner of a Chancellor search is not a legislative game of “gotcha” but an imminent matter of real world consequence.

The 74-year-old Fariña has kept her commitment to serve out most if not all of de Blasio’s term. But there is little doubt that she will soon leave. The state law up for June renewal gives the Mayor power of appointment. Thus it is entirely appropriate and practical for the Senate to now inquire how de Blasio intends to use this power and if, in keeping with his past statement, a small-d democratic process should be put in place.

There are good policy positions on either side. Maybe unilateral appointment is preferable, allowing the Mayor full authority and accountability for his pick. But a public process would allow for full vetting of candidates by parents, the general public, and the press, who will all have serious interest and questions about anyone in line for this highly important job.

A full-blown public search occurs in many districts but, if it is believed that some desirable applicants would decline an open process, the Mayor could nominate and the City Council could conduct an open confirmation hearing, as with federal cabinet appointees (and some mayoral appointments to boards and commissions, and the head of the Department of Investigation).

Instead of making a spectacle of this approval process, the manner in which this mayor and future mayors should appoint the Chancellor is a worthy topic, providing the Legislature with an opportunity to put politics aside for an important policy and electoral debate.

***

David C. Bloomfield is Professor of Education Leadership, Law, and Policy at Brooklyn College and The CUNY Graduate Center. He is the author of American Public Education Law, 3d edition, and other published works. On Twitter @BloomfieldDavid.

***

Have an op-ed idea or submission for Gotham Gazette? Email This email address is being protected from spambots. You need JavaScript enabled to view it.

Inside New Yorkers’ Satisfaction, or Lack Thereof, with City Services

(photo: Michael Appleton/Mayor's Office)

New Yorkers are notoriously opinionated, but how often do they get to tell city leaders what they think?

In January the Citizens Budget Commission surveyed 72,000 randomly selected households across the five boroughs to ask about satisfaction with city services and quality of life. More than 10,000 New Yorkers responded and the results speak loudly about the areas where city leaders must focus on improvement.

Overall only 44% of city residents rate city services as “excellent” or “good.” New Yorkers are most dissatisfied with services for homeless people (14% positive), public housing (20%), services protecting at-risk children (23%), and maintenance of streets and roads (39%). Only 20% believe the City spends tax dollars wisely.

Only half of New Yorkers are satisfied with quality of life in the city overall. Grievances include traffic, air quality, street noise, and rat control. Respondents identified infrastructure, safety, housing, and traffic/mobility as the most important issues requiring greater attention from city government.

Demographic information collected also reveal disparities in ratings between white non-Hispanic residents and Hispanic and black residents. White residents are generally more satisfied than Hispanic and black residents: On 13 of 45 indicators, the disparities in ratings exceed 12 percentage points. For example, 74 percent of white residents were satisfied with their neighborhood as a place to live compared to 50 percent of Hispanic and black residents.

These data provide a valuable management tool to citywide elected leaders, and the Citizens Budget Commission will be analyzing and releasing community board results in coming weeks that will prove useful to local elected leaders, as well.

Surveys gauging satisfaction with city services should be a regular part of how the city does business, but city agencies rarely ask their customers to rate their performance. The results add an important lens to the reams of management data regularly collected and reported; these metrics may not be calibrated to capture results that residents actually care about. For example, the Parks Department consistently states that cleanliness and condition of its parks and playgrounds is acceptable in 85% of cases; however, approximately 55% of New Yorkers rate neighborhood playgrounds and parks positively.

The City of New York conducted a broad citywide satisfaction survey only once before, in 2008. CBC believes city government should conduct such a survey regularly to capture vital insights that can guide administrators in improving government performance. The Mayor and City Council should now create and make public a plan for improvement in the areas that city residents found wanting.

***

Maria Doulis is vice president at the Citizens Budget Commission. On Twitter @MariaDoulis and @cbcny. Read the results of the CBC survey here.

***

Have an op-ed idea or submission for Gotham Gazette? Email This email address is being protected from spambots. You need JavaScript enabled to view it.

We Must Pair Raise the Age with Restorative Justice

Mayor de Blasio in a restorative circle (photo: Ed Reed/Mayor’s Office)

There has been a great deal of celebration following passage of “Raise the Age,” legislation in New York that will end the practice of trying 16- and 17-year-old criminal defendants as adults. And rightfully so -- this will go a long way to dam the school-to-prison pipeline; we should be cheering. But rarely does a key strategy that helps students make better decisions and avoid arrest make headlines: restorative justice.

Like our justice system, our schools need to move away from overly punitive consequences and invest the resources to implement practices that address the root causes of misbehavior and set students on a path to long-term success.

Students need supports, not suspensions, to grapple with the larger problems that often lead to their misconduct. Students who have experienced trauma come to school carrying emotional baggage that impacts how they act in class. In low-income communities, such as the one I have served for six years, it is not uncommon for students to have suffered trauma from poverty, violence, and discrimination. I have a student who has bounced around foster families. Another student witnessed his dad get beaten by gang members. Relying on inflexible, insensitive, zero-tolerance discipline policies only compounds the mental, emotional, and academic damage from trauma and does not give students the tools to deal with challenges constructively and overcome them.

Even as New York has made a huge push to reduce suspensions, little has been done to support educators like myself to learn alternatives, such as restorative justice practices. Three years ago, I transitioned from my role as a math teacher to a dean. Teachers would send misbehaving students to my office, and I would hear their infraction, and unaware of alternatives, I would administer the punishment school protocol decided was appropriate. But after my first year, I knew detentions and suspensions were not having a long-term impact on student behavior. Unsure of a better way to handle discipline, I leaned on my abilities to foster relationships with students that I had honed as a teacher. As I began to see success with this approach, I sought out methods that leveraged relationships to improve behavior and stumbled on restorative practices.

The restorative approach to discipline is anathema to most educators’ training, and making the shift from punitive to restorative takes time, training, and buy-in.

Although my district offered little guidance, I knew I had to initiate this change for the sake of my students. In my free time I watched restorative justice videos on YouTube and attended external professional development. Transitioning from a punitive mindset, in which I evaluated a child’s misstep and doled out the commensurate consequence, to a restorative mindset, in which I sought to understand and address the cause of the misstep, was transformative. But it was also a difficult journey that could have been made easier with assistance from the district.

Now when students enter my office, they come in knowing we will have restorative conversations seeking to get to the root of the issue that brought them there. Students take responsibility for their actions and together we determine how to heal the situation.

An example of this was a recent fight between two high school students. Instead of suspensions, together they worked on a powerpoint on the perils of fighting and presented their findings to an eighth-grade group. Through this activity, the students learned from their mistakes, repaired the damage, and took responsibility to share their knowledge. That is the power of restorative justice; a suspension could never have achieved these outcomes. Interventions like these have reduced our suspensions by 55 percent. Imagine the difference if every school used restorative justice, and if the resources were there to help them do it.

But the beauty of restorative justice is not just the numbers, it’s the relationships. My teachers have seen the power of these relationships, and are taking it upon themselves to bring restorative justice to their classes. Now educators, and even student leaders, are spearheading restorative justice practices in my school. But they, and others around the state, need help. It’s time that New York build on it’s Raise the Age reforms by training our teachers in positive behavioral interventions that keep our kids in schools, not prisons.

***

Barry Price has been a math teacher, dean, and basketball coach for 11 years and is a member of Educators for Excellence-New York.

***

Have an op-ed idea or submission for Gotham Gazette? Email This email address is being protected from spambots. You need JavaScript enabled to view it.