The Limits of Community Policing

NYPD Transit (photo: @NYPDLTrain)

We share many of the recent concerns about overly aggressive, discourteous, and unlawful policing that have been raised in the last several months. Every day hundreds of mostly poor and non-white New Yorkers have unwanted and problematic interactions with the police including unjustified stops and illegal searches, frequent issuances of summonses for non-criminal behavior, and harassment and intimidation by police. Therefore we applaud the holding of a hearing Tuesday by the Public Safety Committee of the New York City Council on improving policing. There is a need for major reforms in how policing is conducted in New York City.

We are very concerned, however, that the leadership of both the NYPD and the City Council are proposing to add 1,000 police officers to the NYPD headcount under the guise of expanding community policing. Too often, community policing means more intensive and invasive policing of minor disorderly behavior that serves to criminalize mostly people of color without dealing with the underlying causes of this behavior like poverty, homelessness, problematic drug use, mental health issues, and more.

The majority of New Yorkers are not actively engaged in the political life of their local neighborhood. Some may be politically active in other venues, others may be focused on national or international concerns, and most are caught up in the daily struggles of home and work.

Part of the problem with so-called community policing lies in the nature of community. Those who are active in community affairs are not always representative of the full diversity of views and experiences in our many neighborhoods. Community Boards and Precinct Community Councils tend to be populated by long-time residents, those that own rather than rent their homes, business owners, and landlords. The views of renters, youth, homeless people, and the most socially marginalized are rarely represented in these bodies.

Community policing tends to turn all neighborhood problems into police problems. Across the country, community police programs have been based on the idea that the community should bring its myriad of concerns about the condition of the community to the police, who will work with them on developing solutions. Invariably, however, the range of community problems extends far beyond serious crime. Why should the police necessarily be the sole or even lead agency in developing strategies to address community concerns about disorder and public safety?

One of the most frequent concerns of neighborhood residents is the presence of low level drug dealing and use. This generates a tremendous number of calls to 311 and 911. Enhancing the ability of police to respond to these community concerns will just further criminalize people involved with low level drug use and sales. The failed "War on Drugs" strategy of criminalizing these activities has done nothing to reduce the availability and negative effects of drugs on individuals or communities, has produced substantial negative collateral consequences for those arrested, and has been a major drain on city resources. The cost of running each bed at Rikers Island comes to over $150,000 a year; money better spent on prevention, harm reduction, treatment, and jobs programs.

There is extensive research that shows that most complaints that "community representatives" take to the police are about "quality of life" problems rather than serious crime. People tend to raise concerns about local disorderly conditions such as noise and traffic, or public behaviors they find annoying such as small-time drug dealing, prostitution, and any gatherings of young people. More intensive police attention to these "community" concerns will invariably lead to further unnecessary and counterproductive harassment and criminalization of many of New York's poorest and most vulnerable.

As an example, at a recent 67th Precinct Community Council meeting in Flatbush, Brooklyn the main complaint of community members was the regular presence of homeless people in and around businesses at the corner of Church and Nostrand Avenues. Some of these people had obvious mental health problems and others panhandled for money for subsistence purposes. The local police commander pledged to respond to these concerns but acknowledged limited capacity and resources to do so. Increased police responsiveness to these complaints, in the absence of new services, will lead to the harassment and arrest of these people in the name of community policing. This is not the kind of improved policing we need.

To the extent that police need to be involved in managing quality of life community concerns, it should be restricted to responding to truly dangerous conditions. The police could also play a role as gatekeeper to enhanced services, such as how Seattle's Law Enforcement Assisted Diversion (LEAD) program diverts low-level drug offenders and sex workers to social services instead of jail. For too long the city has over-relied on the police as first responders to a range of community concerns that might better be dealt with through other city agencies. The police primarily have punitive tools at their disposal, such as arrest and the use of force. What is needed instead are responses that are less punitive and provide real pathways out of addiction, joblessness, homelessness, and poor health.

We do want the police to be more courteous, professional, and respectful, but expanding the ability of police to respond to community concerns will lead to more criminalization of people trying to survive when their most basic needs are not being met. Therefore, we oppose any increase in the number of police at this time and instead call on the City Council to use whatever resources it would have used to increase the headcount of the NYPD to instead invest in supportive housing, harm reduction programs, evidence-based drug treatment, and health services that can play a much more positive and sustained role in reducing very real community concerns about disorder and public safety.

***

by Alyssa Aguilera and Alex S. Vitale

Aguilera is Political Director at VOCAL-NY.

Vitale is Associate Professor of Sociology at Brooklyn College and author of City of Disorder: How the Quality of Life Campaign Transformed New York Politics.

***

Have an op-ed idea or submission for Gotham Gazette? E-mail editor Ben Max: This email address is being protected from spambots. You need JavaScript enabled to view it.

A Short-Sighted Garbage Plan

(photo: @wasterecycling)

Effective management of waste is a topic that concerns many individuals, community leaders, and business organizations, especially when new proposals presented in the City Council threaten hard-earned jobs in the waste and recycling industry.

On February 13, union workers, city council members, business leaders, and waste industry experts joined forces to oppose Intro. 495, a proposal that seeks to reduce waste transfer station capacity in select neighborhoods in New York City.

The idea behind the legislation is attractive, but naïve, as it simply glazes over current problems without providing real waste and recycling processing solutions. The proposal aims not to reduce waste, but simply to distribute it to different neighborhoods in the city. In doing this, Intro. 495 actually adds truck miles throughout the city as sanitation trucks will have to travel further to these alternative transfer stations, and will result in higher costs for New York City businesses.

Proposals like Intro. 495 would also destroy good-paying jobs. Despite claims from opposing parties, private waste companies are required by federal, state, and city law to ensure their trucks are in good working order for their trained workers and the communities they serve. Intro. 495 would eliminate many jobs in a workforce predominantly composed of people of color. These opposing parties are unions that represent a tiny fraction of the private sector waste industry, and are trying to use Intro. 495 to further their own interest while harming the majority of workers who would be adversely affected by this ill-conceived plan.

New York City produces more than 35,000 tons of waste every day. Were the marine transfer stations called for in the plan to open, around 5,700 tons per day would be diverted to these facilities. As a result, more than 400 trucks per day would be redirected from areas targeted by Intro. 495. These are part of the City's Solid Waste Management Plan, which is in the process of being implemented. We firmly believe careful planning and measurement should be a priority before passing laws that will adversely affect communities, jobs, and our environment.

Waste workers work when it's sunny, raining, or blistering cold outside. They don't get a "day off" when natural disasters hit our fast-paced city. They quickly respond to emergencies in order to keep New York City open for residents and commuters. The transfer stations targeted by Intro. 495 played a crucial role in managing debris after Superstorm Sandy, and this capacity would not be available if the bill is enacted.

For all of these reasons, dozens of representatives from Laborers Local Union 108, United Service Workers Union Local 339 and the International Union of Journeyman & Allied Trades Local 726, NW&RA members, and business leaders joined to express their opposition to Intro. 495 on the steps of City Hall on January 22.

We are open to discuss other options with the City Council and de Blasio Administration to reach a more viable solution without jeopardizing union jobs and neighborhoods. We know already that Intro. 495 is not the answer to this complex problem.

***

Tom Toscano chairs the National Waste Recycling Association NYC Chapter and is CFO of Mr. T Carting.

***

Have an op-ed idea or submission for Gotham Gazette? E-mail editor Ben Max: This email address is being protected from spambots. You need JavaScript enabled to view it.

The Case for Mayoral Control

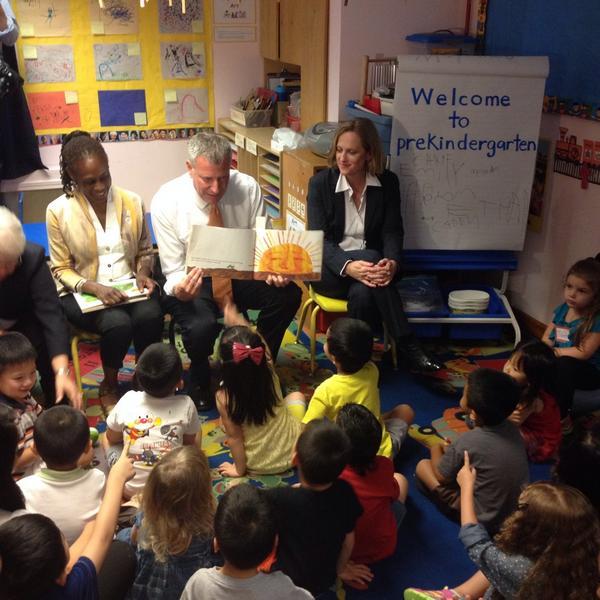

Mayor de Blasio reads to students (photo: @MelindaKatz)

The state legislature will soon decide whether to reauthorize, amend, or eliminate mayoral control of the New York City public schools. Mayoral control should be extended and, as suggested by the Mayor, made permanent - with the possibility of amendment as with any law.

The most important reason to keep mayoral control is to keep city funding of our schools at a high level. Prior to mayoral control there were incessant and critical battles over the city's underfunding of our schools. That in part resulted from the demise of the old Board of Estimate, which set the City budget, and its mirrored membership on the Board of Education, consisting of single representatives of each Borough President and 2 mayoral appointees.

Once the Board of Estimate was eliminated, the connection between operational and budgetary authority of the schools was lost. The effect was immediate and harsh. An era of underfunding ensued, propelled by a new City Charter giving the Mayor strong budgeting powers but without authority for schools. As a result, the Board of Education budget withered while mayoral agencies were privileged.

Only with mayoral control did city funding increase and increase substantially. We no longer hear cries of impoverishment over the city's education budget. The fight now is over State funding because mayoral control means more money. Pure and simple.

While adequate city funding is the main reason for retaining mayoral control, there are additional benefits. The old Board of Education was a recipe for paralysis because six appointing authorities controlled seven votes on the Board. As Board Counsel, I saw petty political horse trading, patronage, and personal ambition mean more than quality education since no one was in charge. Kids, parents, and taxpayers bore the consequences, not those who bore real responsibility. A parade of short-term Chancellors came and went, leaving a legacy of instability that subverted any stirrings of instructional success.

Mayoral control has given us continuity and stability, prerequisites for educational improvement. Despite the churn of the last decade - and my strong public opposition to Bloomberg/Klein policies - leadership stability has been a plus. (Remember the chaos of Cathie Black!) Nothing is worse for a system than constant leadership changes and mayoral control has brought surprising system stability.

And stability is good for direction. Like it or not, clear institutional direction - the ability to make and implement decisions - is another requirement of strong institutions. I know that many of my friends claim the need for "checks and balances," but public education is not a national government to be protected from extremes of political volatility. It is fundamentally an executive function, requiring the clarity of mission and organizational structure that comes from having someone in charge.

It is easy to criticize the present scheme; harder to find a practical alternative, especially under a Charter giving the Mayor such strong fiscal power. Why believe shared authority will work when it failed before? Why believe elections will make schools less political and any more stable? When Board of Education members served fixed terms, we had the ridiculous spectacle of Board appointees betraying their Borough Presidents to side with Rudy Giuliani in a political power play, resulting in the anti-Dinkins "Gang of Four." This was not about kids but personal ambition.

If we need tweaks - and I warn of opening the door to all manner of tweakers - City Council advice and consent over the Chancellor's appointment and removing the Chancellor from PEP membership would create greater community input into DOE leadership and more pluralism in PEP deliberations.

As a former President of the Citywide Council on High Schools, I see the need for greater collaboration between the DOE and parent groups at the central, district, and school levels but that requires non-legislative solutions, not more regulation.

Much of the current opposition to mayoral control is a reaction to the Bloomberg years. But we have only begun to explore the opportunities and proven strengths of the law. If mayoral control has so far not yielded school policies attractive to particular constituencies, that is not the problem of governance but those who govern. Let's not be led astray by believing our policy preferences can be guaranteed by some new structure.

***

David C. Bloomfield is Professor of Education Leadership at Brooklyn College and The CUNY Graduate Center. He is the author of American Public Education Law, 2nd edition, among other works.

***

Have an op-ed idea or submission for Gotham Gazette? E-mail editor Ben Max: This email address is being protected from spambots. You need JavaScript enabled to view it.