Op-Ed: Stop-And-Frisk From A Mother's Perspective

I often wonder if I have what it takes to raise my black son in New York City.

While concerns about navigating public school application processes and scheduling play dates are common topics among parents, what often goes unspoken is something far more important: the unique challenges that come with parenting a young boy of color in New York City.

With nothing promised for young blacks and Latinos other than low expectations, street violence, negative peer influences and persistent police suspicion, how do we make sure that that our sons grow up safe and thriving? One step is putting an end to stop-and-frisk.

The New York City Police Department’s stop-and-frisk policy and all of its implications on crime and race are now at the forefront of political and social conversation.

With a decision pending in Floyd v. New York City, a high profile federal case challenging these practices, along with relentless community activism and a hotly contested mayoral campaign, now is the time to push for leadership that acknowledges the crisis in policing and proposes criminal justice policies and social reforms that will actually keep our young people safe without criminalizing them.

{sidebar id=14 align=right}

In a recent mayoral debate, Bill Thompson, the only candidate to address this issue from the perspective of parenting a black son, said “I’m the one who has to worry about my son getting shot on the streets of New York … And at the same point, I don't have to sacrifice his constitutional rights to make sure he is safe … I can have them both."

As a parent, I worry about my son’s safety. As a lawyer, I worry about his rights. Stop-and-frisk promotes neither.

In this climate of heated discussion, the mayoral candidates must acknowledge that stop-and-frisk has proven so damaging and polarizing a practice that it has become New York City’s civil rights issue of the day. Those vying for New York City’s top office must articulate proposals for credible alternatives to stop-and-frisk policing that go beyond weak promises to train police in cultural sensitivity and professionalism.

New York’s next mayor can learn from the successes of other cities that have developed anti-gang initiatives, gun control programs and community collaborations.

Ironically, proponents of stop-and-frisk often cite parental desire for increased youth safety as one of the most compelling reasons for continuing this policy. Like all mothers and fathers, parents of young men of color want their children safe from drugs, violence, and many of the other harmful influences of New York City’s streets.

Yet, draping stop-and-frisk in emotional appeals to safety overshadows its damaging reality. Moreover, those arguments overlook evidence showing that the decline in serious crime in New York City cannot be directly attributed to stop-and-frisk.

While violent crimes fell 29 percent in New York City from 2001 to 2010, other large cities that do not rely on an aggressive stop-and-frisk policy — such as Los Angeles, Baltimore and New Orleans — experienced larger declines in violent crime. In terms of illegal gun recovery, according to the New York Civil Liberties Union, from 2003 to 2012, the NYPD increased stops by 372,060, but recovered only 96 more guns, amounting to an additional recovery rate of 0.02 percent.

In fact, in 2011, the NYPD recovered illegal guns four times more often through methods not involving street stops.

Young black and Latino men are indisputably the targets of stop-and-frisk. Male youth of color between the ages of 14 and 24 comprise less than 5 percent of this city’s population, yet they accounted for 41 percent of stops in 2012.

Appallingly, more than 90 percent of black and Latino youth stopped by the police were innocent of any wrongdoing.

These unwarranted stops are not without consequence.

Most critiques of stop-and-frisk focus on damaged police-community relationships and the fraying of youths’ willingness to assist police investigations. While these are significant costs, parents should also consider the emerging evidence of the emotional and psychological harm caused by these often disrespectful, humiliating, and threatening interactions.

Nicholas Peart, a young black man named as one of the plaintiffs in the Floyd suit, gave a first person account of the toll of being stopped and frisked: “Essentially, I incorporated into my daily life the sense that I might find myself up against a wall or on the ground with an officer’s gun at my head. For a black man in his 20s like me, it’s just a fact of life in New York.”

There are many facts of life that I am prepared to teach my young son. This should not be one of them.

Nicole Smith Futrell is a clinical law professor in the Criminal Defense Clinic of Main Street Legal Services at the City University of New York School of Law.

Shining A Bright Light On Government Spending

Some say the West Coast has the best beaches, the Midwest has the friendliest people, and that you can't beat the cheesesteaks in Philly.

But financial transparency? Fugghedaboudit. New York City’s got everyone beaten by a mile.

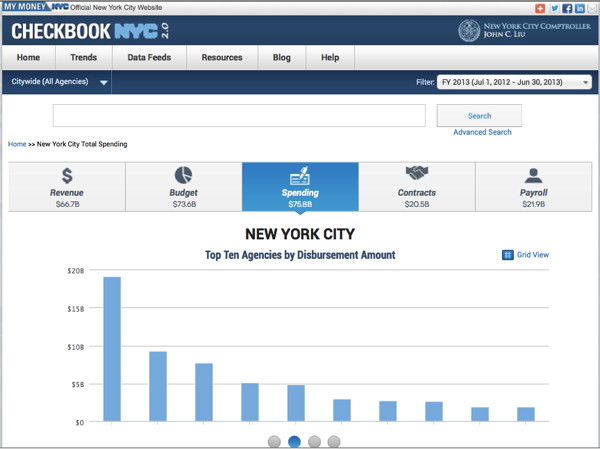

That’s not just our opinion. That’s the view of the United States Public Interest Research Group, which in January named New York City the most transparent municipal government in the nation on the strength of Checkbook NYC, a website created by my office that allows users to view City spending.

Recently, however, we took steps to share the honor: we made the source code for CheckbookNYC.com freely available to every government that wants it.

This “open source” release means that cities and states across the country can leverage our investment in Checkbook NYC to create similar websites of their own.

We hope other places will like New York-style transparency, and we think they will.

On CheckbookNYC.com, you can find comprehensive, up-to-date information about the money that flows into or out of the City’s accounts. Details about spending, contracts, payroll, budget, revenue — it’s all there.

And the site is accessible to techies and luddites alike. Search functionality, graphic visualizations, and an intuitive interface make it easy for anyone to become a fiscal watchdog.

We built it for a simple reason: shining a bright light on government spending helps root out waste and ensure that tax dollars are spent wisely.

When governments know that their spending decisions can be easily scrutinized, they are more likely to use their resources prudently.

The site has the potential to save taxpayers big bucks. Imagine: If Checkbook NYC encourages the City’s decision-makers to rethink just one-tenth of one percent of our annual $70 billion budget, that’s a $70 million savings.

{sidebar id=14 align=right}

And that’s just for starters. The site can further drive costs down by encouraging competition among vendors and serving as an early warning system for projects that start to go over budget.

We aren’t giving the code away just out of the goodness of our hearts — we’re nice, but not that nice. We also want to mobilize the collective talents of local governments and technology engineers to improve upon what we’ve created so far.

It’s a civic experiment that we can all benefit from. Say Los Angeles starts using Checkbook, and then develops a new way to map where tax dollars are spent; every government that uses the platform will be able to benefit from Los Angeles’ innovation.

Following this theory, the more rapidly and widely Checkbook is adopted by other states and cities, the better it will become.

To encourage widespread adoption, two of the leading providers of government accounting systems, Oracle and CGI, are building Checkbook “adapters.” Their clients — hundreds of governments across the country — will be able to feed their financial data into the Checkbook system with the flip of a switch. And the company we worked with to build the site, REI Systems, is lending their technical expertise to help get open-sourcing off the ground as well.

The code for Checkbook NYC is available on GitHub.com. Local governments and techies should take a look, and get involved.

No one’s ever going to stop debating about where to find the nicest places, friendliest people, or tastiest grub. But when it comes to financial transparency, we can work together and all become the best.

John C. Liu is the New York City Comptroller.

Gov. Cuomo’s Tax-Free New York Initiative Makes Economic Sense

Upstate New York was once the economic envy of the nation. We were truly the Empire State.

Triggered initially by the public-private partnership that built the Erie Canal and later maintained by the construction of the New York State Thruway, companies such as Kodak, IBM, Carrier, General Electric, Syracuse China, General Motors, and Chrysler built major plants employing thousands of workers. Today, most of those manufacturing plants are closed and the jobs are gone.

Over the past several decades, we have seen economic development proposals ranging from casinos to hydraulic fracturing. Nothing has worked, and upstate New York remains stuck in the financial mud.

A new approach is needed if New York State is to grow again.

Increasingly, most of the world’s economic growth can be found in what we call the brain based economy — a marriage of education, high tech, and the design (not the manufacture) of consumer products.

Silicon Valley in Northern California and the Route 128 corridor around Greater Boston are perhaps the best known and most successful examples of economic growth fueled by combining the research and education capacity of first-rate universities, the entrepreneurial spirit of their graduates, and tax incentives provided by state and local governments.

Other states and localities took notice and have successfully copied the model— so successfully that Forbes magazine's recent ranking of best cities for high tech jobs placed Silicon Valley at number seven behind Seattle, the Washington D.C., metropolitan area, San Diego, Salt Lake City, Baltimore and Jacksonville, Fla. All these cities have used lower taxes, education, and available land adjacent to higher education research centers as the formula for economic growth.

{sidebar id=14 align=right}

New York State and New York City have begun to move in this direction. Last month, the New York City Council approved the construction of a $2 billion Cornell University Technology campus and office complex on Roosevelt Island made possible by a grant of free land and up to $100 million in improvements from the city. In Harlem, the city’s Economic Development Corp. is developing space to rent to new biotech firms. Our own university is constructing a new Mind, Brain and Behavior research complex on its new campus in West Harlem, and companies like Google and Yahoo are flocking to New York City.

Upstate, in Albany, the SUNY and the State have partnered to create the now world-renown College of Nanoscale Science and Engineering, where students, faculty and private firms work together and separately to conduct education, pure research and cutting-edge commercial nano-industry products.

CSNE is now bringing this model to projects in Utica, Rochester and Buffalo. In Syracuse, the State and local governments are assisting Upstate Medical University to work with a private developer to create a mixed-use, medical and high tech research, housing and retail complex called Loguen’s Crossing on the site of an abandoned public housing project.

In May, the governor announced “Tax-Free NY,” offering new businesses an opportunity to operate completely free of New York state taxes for 10 years if they locate and partner at any of the SUNY campuses outside of New York City (some commercial space at private universities and 20 underutilized state assets are also eligible for the program). Those taxes that would be suspended include sales, property, and business/corporate taxes, and the employees are exempt from the state income tax for the same ten-year period.

The program already has the public support of the leaders of the state Senate and Assembly, the State Conference of Mayors, and Association of Counties, the Business Council of NYS, the Partnership for New York City, the chancellor of SUNY, and senior executives from GE, IBM, JP Morgan, and Goldman Sachs among others.

But the program is not without its critics and doubters. CSEA, the state’s largest public employee union, sees the program as a give-away to business and unfairly beneficial to the employees of the participating companies. Others say that New York City should be included — the governor responds that it is upstate that is in most need of new jobs. The Conservative Party opposes the program because government will choose who gets the benefits and instead suggests reducing taxes on all businesses.

Academic research on the long-term benefits of tax incentives is inconclusive— time lags need to be considered to accurately assess the full impact of the incentives and firm-level data are seldom available.

Our view is that the economic situation upstate is desperate and we need to experiment with a variety of programs to see what works.

In the words of Franklin Roosevelt, another New York governor during tough times: “It is common sense to take a method and try it. If it fails, admit it frankly and try another. But above all, try something.”

Gov. Cuomo has it right: we need to try things. We need action, not words.

We know that the communities having success in growing their tech and biotech industries have used strategies very similar to Tax-Free NY —leveraging their higher education system, location-based tax incentives, and public-private partnerships.

Particularly given the success of the College of Nanoscale Science and Engineering in Albany, New York should enact the governor’s program.

Eimicke is the founding executive director at the Picker Center for Executive Education at Columbia University. Cohen is the executive director of the Earth Institute at Columbia University. Both are professors in Columbia’s School of International and Public Affairs.