Byford’s Gone and So's His Job; What's Next?

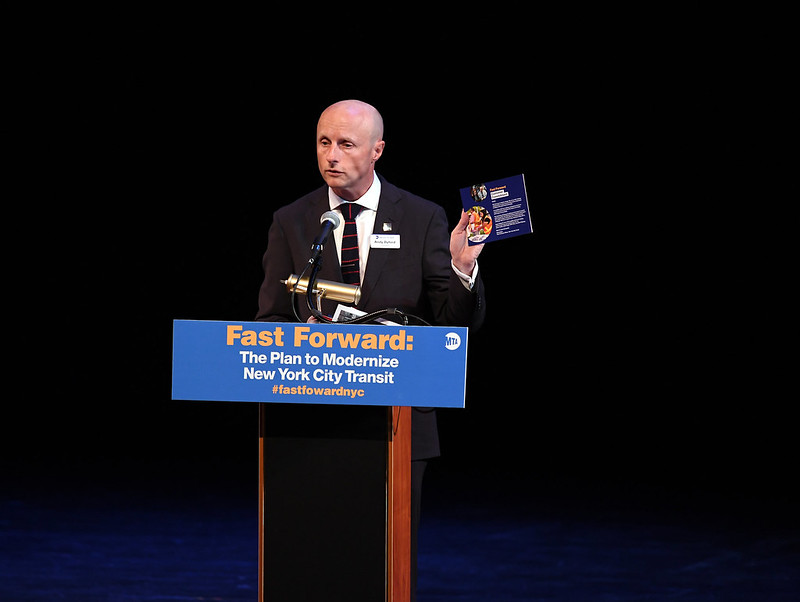

(photo: Marc A. Hermann / MTA New York City Transit)

There will never be another MTA New York City Transit President with the power Andy Byford had when he took the job two years ago. Under Governor Cuomo’s MTA reorganization plan, all future NYCT “Presidents” have been stripped of the power to manage capital projects like replacing signals and switches or buying new rail cars and buses. The next boss of Transit also lost control of a large number of engineering experts and legions of Transit Authority workers who are reimbursed for their time on capital projects.

Going forward, Transit’s capital planning, purchasing, and project management will be done by a centralized, newly-renamed MTA Capital Construction & Development agency. This massive agency is run by MTA Chief Development Officer Janno Lieber, who has immense powers and approves everything from which kind of new bus to buy to who gets to rent the candy stand in the 103rd Street subway stop.

Byford’s departure got so much attention in part because the MTA is going through a wrenching reorganization ordered by the governor that includes eliminating 800 operations workers and 1,900 administrative staff. Amidst this turmoil, Byford was highly respected by rank-and-file workers and riders for hugely reducing subway delays with a mix of hard-headed pragmatism, sincerity, and optimism.

MTA “Reorganization” Pushed Out Byford

It was Governor Cuomo’s reorganization plan, approved in July 2019, just three months after it was mandated by the state budget, that led inevitably to Byford’s resignation.

In his resignation letter, Byford wrote that the “transformation plan...called for the centralization of projects and an expanded HQ, leaving Agency presidents to focus solely on the day-to-day running of service. I have built an excellent team...who could perform this important, but reduced, service delivery role.”

The central tensions in Byford’s relationship was the governor’s inability to share credit with a talented subordinate, penchant for secrecy, and his preference for surprise “man on horseback riding to the rescue” announcements instead of conventional, fact- and expert-based planning.

Byford’s “I’m a global transit expert” worldview came into a head-on collision with the governor’s insistence that the MTA and Byford could use Ultra Wide Band (UWB) radio technology to vastly speed up resignaling the subway system. New signals are a top priority and the core of Byford’s Fast Forward plan, because signal problems are the main cause of subway delays.

The problem is that UWB has not been widely deployed by any leading subway system and is viewed as a promising, but not mature, technology. Signal modernization is also at the fault line of authority over who will fix the subways: NYC Transit or MTA Capital Construction & Development. Since the departure of Byford and then his top signals deputy, Pete Tomlin, control over signal modernization -- and the decision about which lines get new signals first -- appears to be in MTA Capital Construction & Development’s hands.

Byford and Cuomo also famously clashed over the L train tunnel and subway speeds initiatives, when the public saw the governor reaching over the MTA board and MTA CEO to make direct decisions about MTA project management.

Reorganization or Disorganization?

Reinvent Albany and transit advocates have repeatedly warned that the reorganization plan could result in the fragmentation of expertise, and the derailment of Byford’s Fast Forward Plan (both before the passage of the state budget that mandated the change and after, when the MTA’s consultant, AlixPartners, was developing the recommendations).

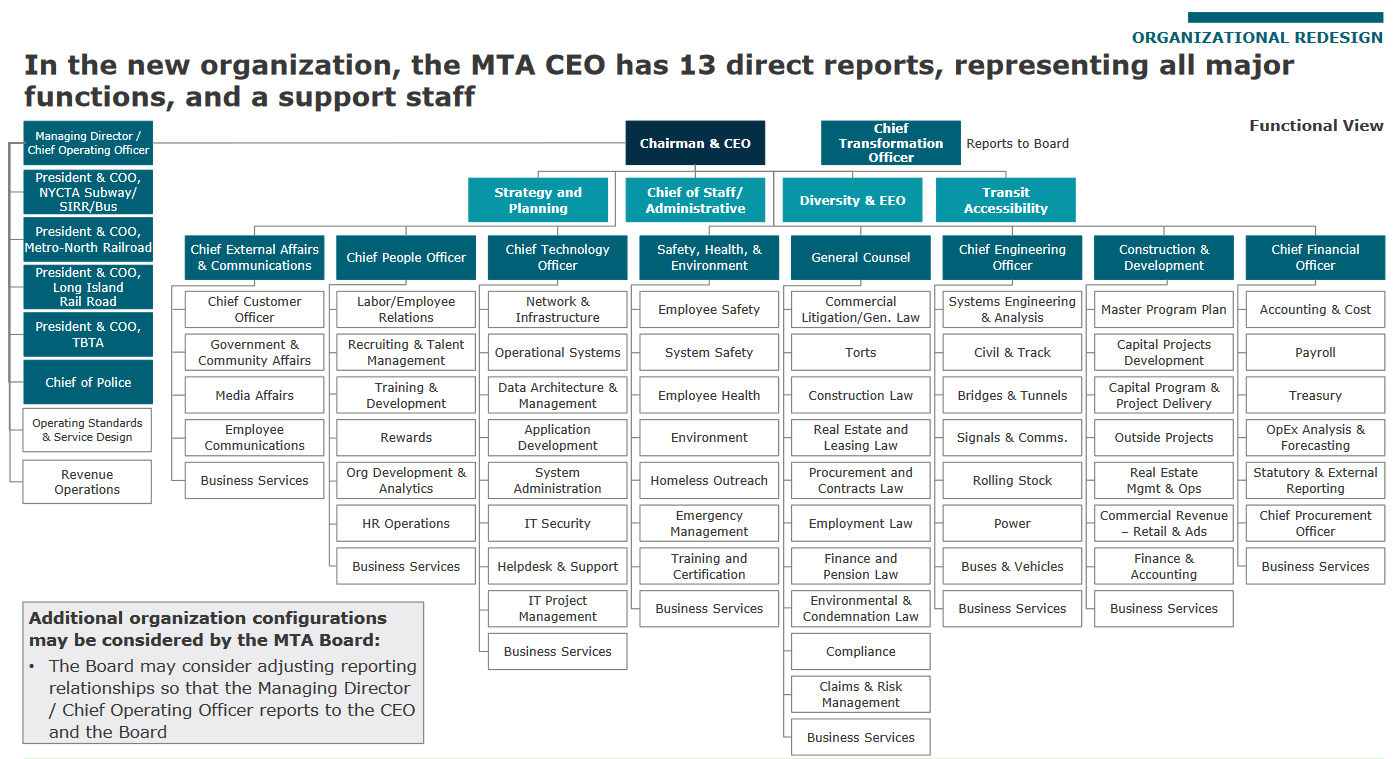

We were concerned that shifting NYC Transit’s talent, like Byford’s signals expert Tomlin, to MTA Capital Construction would result in fragmentation, where the engineering and capital planning staff were separated from operations, creating new silos. One could argue the transformation plan created more than 13 new silos, with many new chief officers -- of operations, engineering, technology, communications, etc. -- all reporting to the CEO/Chair. See the “chief” heavy org chart below.

Splitting NYCT into Subway and Bus Operations?

A June 2019 “draft” version of the transformation plan that was scrubbed before final release proposed separating subways from buses, with all MTA buses merged together under one head. That seems more likely now with Byford’s departure, though not without challenges given the separate collective bargaining agreements for bus operators, as express buses are under the MTA Bus Company, while NYC Transit runs local and select buses.

Buses are too often relegated to second-tier status below subways in terms of public officials’ focus, but not under Byford. Byford made a point to own buses equally with subways, as seen through his work on the 14th Street busway and borough-based bus redesigns, which have been long overdue.

Transit advocates at the Bus Turnaround Coalition are working hard to maintain the momentum that Byford helped start, but his departure and the overall reorganization at the MTA leave it unclear who will restore the bus system. Thanks to Bus Rapid Transit, buses have undergone a global renaissance over the last 25 years that has skipped over New York City. With Byford leaving, all eyes will be on Governor Cuomo to ensure that needed improvements are made to both subways and buses.

#CuomosMTA

We hope our concerns are misplaced, and that the governor’s massive reorganization of the MTA will result in big benefits for riders and those who work for the Authority. We hope the governor’s repeated, direct interference in the MTA’s operations will lead to greater organizational focus and effectiveness. We hope that the reported exodus of experienced MTA managers -- some of whom left before Byford -- will allow for new talent and new ideas to rise. We hope the governor lets Janno Lieber do his job, and that Lieber knows what to do with the massive power he’s accumulated with the new MTA Capital Construction & Development agency.

Yes, we hope for a lot of things, so while we’re at it, let’s hope that the governor will take responsibility for the failures, not just the successes of his efforts at the MTA.

***

Rachael Fauss and John Kaehny are, respectively, senior research analyst and executive director of Reinvent Albany. On Twitter @ReinventAlbany.

***

Have an op-ed idea or submission for Gotham Gazette? Email This email address is being protected from spambots. You need JavaScript enabled to view it.

As Cuomo Proposes Excelsior Scholarship Expansion, 6 Things to Know About the Program

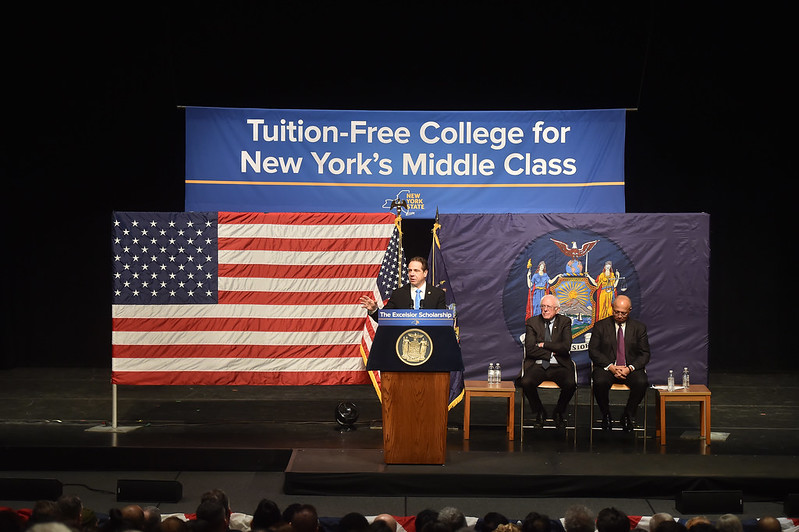

(photo: Kevin P. Coughlin/Office of Governor Andrew M. Cuomo)

In January 2017, Governor Andrew Cuomo unveiled the Excelsior Scholarship, New York State’s “free college” initiative. About 20,000 students were awarded Excelsior in the inaugural 2017-18 year. In 2018-19, the number of scholarship recipients rose to 24,000, and for 2019-20, the Legislature projects an increase to 30,000, which will equal no more than 5% of the state’s public college enrollment.

The 5% figure is small compared to the massive hype that surrounded the program’s rollout. Yet 30,000 beneficiaries is still a large number, exceeding the total undergraduate enrollment at the State University of New York (SUNY) campuses at Albany and Stony Brook, or the combined enrollments at the City University of New York (CUNY) Brooklyn College and City College campuses.

In his January 8 State of the State address, Governor Cuomo proposed to expand eligibility for Excelsior to students from families with incomes of up to $150,000, which is an increase from the current income limit of $125,000. The governor’s executive budget proposal includes a two-year phase-in, with the cap increasing to $135,000 for the 2020-21 academic year and then to $150,000 in 2021-22. For 2020-21, the total budget for Excelsior would be $146 million, up from an expense of $66.4 million in 2017-18.

When Cuomo first introduced Excelsior, it was with two purposes—first, to provide relief to families in the middle-class college affordability squeeze, neither eligible for much existing financial aid nor easily able to pay rising public tuition, and, second, to advance educational opportunity and equity to all New Yorkers. “With this program, every child will have the opportunity that education provides,” he proclaimed.

As a result of Excelsior, the amount of state financial aid distributed to middle-income families has markedly increased. At the same time, aid to the lowest-income students via the state’s Tuition Assistance Program (TAP) and TAP credit program has grown only incrementally with step-ups to keep pace with tuition increases.

With Excelsior, the goal of middle-class college affordability has advanced, yet as it has a wider chasm has opened between the resources available to low-income and middle-income students. Excelsior has never offered that much to low-income students and opening up Excelsior to higher-earning families won’t change that.

Now that the governor is proposing to expand Excelsior, below are six important things to know about the program, including that as it is now constituted, it offers relatively little to low-income students, community college students, and CUNY students.

1. Excelsior does not help low-income students.

The lowest income students in New York State receive enough financial aid from federal Pell grants and the TAP program to cover the full costs of CUNY tuition or SUNY tuition. As “last dollar” awards, Excelsior scholarships only go to students who have tuition balances remaining after exhausting all other aid.

The lowest income students, already going to public colleges tuition-free as a result of Pell and TAP, typically gain nothing financially from Excelsior. Thus, a “free college” initiative that might seem like a financial windfall for the lowest income students does not actually reward them additional aid.

This is a shame, as much research, often coming from the Hope Center for College, Community, and Justice, documents that low-income college students’ financial challenges compromise their abilities to stay in college and to progress toward graduation.

2. Excelsior benefits students from families that are “upper” low-income and middle-income.

If the lowest-income students don’t benefit from Excelsior, who does? The answer is middle-class students and near middle-class students with tuition balances remaining after accounting for Pell and TAP. My prior reporting profiled grateful middle-class students at Brooklyn College and SUNY Albany for whom Excelsior has been a difference-making lifeline.

Students from families with taxable incomes of between $80,000 and $125,000 are in the sweetest spot. At $80,000+ in taxable income, families generally phase out of eligibility for Pell or TAP. For these students, Excelsior flips the script from a full tuition bill to none.

As the income cap has increased to $125,000 from the initial cap of $100,000 in 2017-18, the program has become even more of a middle-class tuition relief program than it was during its inaugural year.

The proposal to increase the upper income limit to $150,000 would extend the program towards upper middle-class territory. According to the Pew Research Center, a household of three with an income of $50,697-$152,092 is middle-class, with that defined as having an income of between two-thirds and double the national median income adjusted for household size, with the figures modified to $60,49-$181,496 for household sizes of four.

Data from the NYS Higher Education Services Corporation (HESC), which administers Excelsior, is presented in the scattergram below and shows that the program, during its inaugural year, provided more substantial benefits to students at colleges serving predominantly middle-income and near-middle-income students than colleges serving predominantly low-income students. This is as would be expected given the design of Excelsior, but the magnitude of the program’s bias in favor of middle-income students is especially stark when visualized.

In the scattergram, each of the state’s public CUNY and SUNY colleges is represented by a point on the coordinate plane. The horizontal axis captures the percentage of students at each institution receiving Excelsior while the vertical axis captures the percentage of students receiving Pell grants. The Pell grant percentage at a college is a strong proxy for the percentage of low-income students at the institution.

In the scattergram, the lower the Pell grant receipt rate (and by proxy, the more middle-class the student body), the higher the percentage of students who received Excelsior. (The methodology section at the end of the article describes the data sources and their limitations.)

The lower quadrants of the scattergram are an area worthy of special attention. In 2017, 12 of the state’s public colleges had less than 40% of their freshmen receiving Pell grants. These colleges had the most middle-class student bodies among the state’s public colleges and included schools such as SUNY Geneseo and SUNY Binghamton. At these 12 campuses, 6.3% of students received Excelsior in 2017-18, nearly double the 3.2% statewide rate for the same year—and this was as a number of these campuses enrolled significant numbers of out-of-state students not eligible for Excelsior.

Meanwhile, as an example from a campus with a high-percentage of low-income students, at CUNY LaGuardia Community College, whose data point is in the upper left corner of the scattergram and where 73% of freshmen received Pell grants in fall 2017, only 0.3% of the student body received Excelsior, far below the 3.2% statewide rate.

The entire scattergram illustrates an inverse relationship between Pell grant receipt rates and Excelsior award rates.

3. Excelsior hardly benefits community college students.

Excelsior recipients are especially scarce at the community colleges, where 1.7% of students were awarded Excelsior in 2017-18, compared to 4.6% of students at the four-year colleges.

Excelsior is relatively unique among “free college” initiatives in extending benefits beyond community colleges, and this actually reinforces the historic under-funding of community colleges compared to four-year colleges. Of all 2017-18 Excelsior award recipients,75.7% were students at four-year colleges and 24.3% students at community colleges, even though community college students are about half of the state’s public college enrollment.

The vast differential in award rates between community college students and their four-year college counterparts is driven by two factors. First, community college students are more likely to benefit from fully-covered tuition via combined Pell and TAP awards than are four-year students. This is in part because the lower tuition amounts at the community colleges generate fewer cases where tuition gap-filling Excelsior awards are needed. Second, Excelsior rules that require full-time attendance, continuous enrollment, and earning a heavy 30 credits each year eliminate from eligibility many community college students.

In dollar amounts, $12.2 million in Excelsior funds, representing 18.3% of the total Excelsior budget, went to community college students in 2017-18, with the balance of $54.2 million, or 81.6%, going to four-year college students.

4. Excelsior hardly benefits CUNY students.

Excelsior also does not register much of a presence at the CUNY colleges. In 2017-18, the 18 CUNY colleges enrolled a 16.3% share of Excelsior scholarship recipients, with the balance of 83.7% of recipients attending SUNY colleges, even though CUNY students comprise 38.8% of the state’s public student enrollment. The number of recipients is small at SUNY but minuscule at CUNY.

Excelsior recipients are virtually non-existent at some community colleges. CUNY Hostos Community College had just 12 awardees, and CUNY Kingsborough Community College had only 42.

The key driving force for the differential is that CUNY students are more likely than SUNY students to have lower family incomes for which Excelsior offers no additional financial benefits. CUNY students also are more likely than SUNY students to be ineligible by attending part-time or by not earning 30 credits annually.

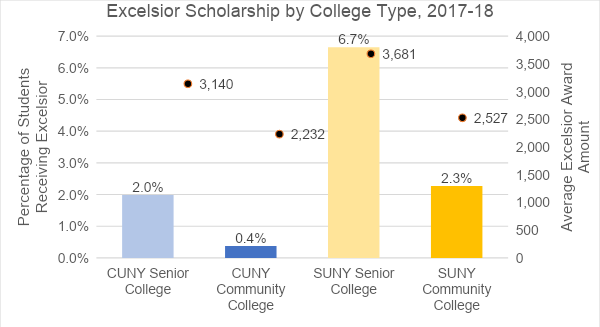

As depicted in the chart below, 0.4% of CUNY community college students received Excelsior in 2017-18, compared to 2.0% of CUNY senior college students, 2.3% of SUNY community college students, and 6.7% of students at SUNY four-year institutions. SUNY four-year college students also received financially larger awards, on average, though this is likely the result of these students receiving awards for two semesters at particularly high rates rather than just awards for single semesters.

In dollar amounts, $9.9 million in Excelsior aid went to CUNY students compared to $56.4 million to SUNY students. The discrepancy between the amounts to CUNY and SUNY students is steep.

The bar chart below is another telling visualization, presenting the imbalanced Excelsior awards for all of the state’s public colleges. The schools with the highest percentages of students receiving Excelsior awards tend to be mostly SUNY four-years. The schools with the lowest award rates are mostly CUNY two-years.

In theory, “free college” seems like a neutral idea—free to all!—yet in reality, Excelsior’s rewards are targeted. The by-product of Excelsior’s income and academic eligibility criteria is a funding imbalance between CUNY and SUNY constituencies.

Today, the imbalanced distribution of Excelsior awards is almost certainly more biased in favor of SUNY four-year schools than it was in 2017-18. The SUNY four-years likely have the highest percentage of students enrolled from families with incomes of between $100,000 and $125,000, an income range presently covered by Excelsior that was not during the program’s inaugural year. If Governor Cuomo is successful in expanding the income range another $25,000 to $150,000, then the imbalance in the distribution of funds between CUNY and SUNY would likely deepen further.

Data from the completed 2018-19 academic year, when the income cap was raised by $10,000 to $110,000, could shed light on the impact of marginally increasing the income cap but so far HESC has yet to release that information to the public.

5. The Excelsior program is not incentivizing more students to enroll in college.

One redeeming value for Excelsior could be that its simple message of “free college,” broadcast widely by Governor Cuomo and in the news media, may be incentivizing more New Yorkers, especially of limited means, to enroll in college and to achieve college degrees.

Research from Hieu Nguyen, a researcher in the Department of Economics at the University of Tennessee, suggests that, at least in its first year, Excelsior did not catalyze an enrollment boom. According to Nguyen’s 2019 article in Education Economics, which compares enrollment patterns in New York State with enrollment patterns in other states using a quasi-experimental statistical design, Excelsior had a “negligible effect” on boosting higher education enrollment in the state.

It should not come as a surprise that Excelsior didn’t jumpstart college enrollment given that it has such restrictive eligibility criteria and offers no financial benefits to most low-income students.

The research, however, is not definitive, as Nguyen’s research explored just Excelsior’s first year. There may have been an Excelsior-related bump in college enrollment in the program’s second or third years, once there were longer periods of time for the message of “free college” to influence high school students’ developing attitudes towards college-going.

6. Excelsior may have positive effects on student retention and on-time graduation.

Another positive feature for Excelsior could be that it contributes to increased retention and graduation rates.

Yet there is no conclusive research on Excelsior’s impacts on retention and graduation. In September 2019, the governor’s office announced that the two-year graduation rate for Excelsior students at SUNY community colleges was 30% compared to a non-Excelsior graduation rate of 11%. For CUNY community college students, the two-year graduation rate was also 30%, compared to 12% for non-Excelsior students. This is a positive sign, yet Excelsior and non-Excelsior students differ in substantive ways, most notably by income level, and more rigorous research is required, which is only possible if more Excelsior data is released.

In his State of the State address, Governor Cuomo declared, “The national progressive dream of free college tuition is a New York reality.” Yet for New York State’s “free college” program to be a strong model to other states and cities, there must be reforms to the entire New York State financial aid system such that it distributes more aid to low-income students, rather than introducing a costly subsidy to families in the $125,000-$150,000 income range.

*****

Methodological Notes:

The HESC data on the Excelsior Scholarship awards from 2017-18 is posted on the Open NY website. The figures for SUNY Tompkins County Community College (TCCC) are “pending final eligibility determination,” according to HESC (email correspondence), and have been excluded.

For each campus’ total number of undergraduate students, the fall 2017 NCES IPEDS enrollment figure was used. The number of Excelsior recipients at each college was divided into that college’s fall 2017 IPEDS enrollment figure to calculate the percentage of students at each campus receiving Excelsior.

This is an imperfect approach, as the Excelsior scholarship headcount figures in the HESC dataset are described as being for both semesters of the 2017-2018 award year rather than just for the fall semester. An alternative method would be to rely on the IPEDS unduplicated annual headcount as the denominator for calculating the award rate percentages. This alternative approach would have generated lower award rates and an even more pronounced gap in award rates between community college and four-year college students.

This alternative approach was not employed because the unduplicated annual headcount figure is a noisy variable skewed by summer session enrollments, non-degree enrollments, and other factors. In some cases, unduplicated annual headcount figures are twice the fall 2017 headcount.

As a consequence, the percentages of students receiving Excelsior cited in this article are not precise but are approximate ones employed to show relative differences.

***

Are you a student, parent, school official or other person who has an experience with the Excelsior Scholarship that you’d like to share? If so, contact This email address is being protected from spambots. You need JavaScript enabled to view it..

***

Eric Neutuch is a freelance journalist and former CUNY administrator, 2009-2017.

***

Have an op-ed idea or submission for Gotham Gazette? Email This email address is being protected from spambots. You need JavaScript enabled to view it.

We Deserve The Right To Be Forgotten

(photo: Benjamin Kanter/Mayoral Photo Office)

An old school newspaper editor once told me through a cloud of cigar smoke, “The accusation? That's front page news. The acquittal? You're lucky if that makes the paper at all.”

Being “innocent until proven guilty” is one of the most sacred tenets of the American criminal justice system. But in the modern digital age, “innocence” is something the acquitted or the wrongfully accused never fully achieve, because, on the internet, their name stays forever affiliated with the crime for which they were charged. That’s why we should be pushing to institute a national “Right to Be Forgotten.”

Imagine you are accused of a crime you did not commit. After what was most likely a long and traumatic trial, the judge or the jury finds you did not commit the crime, and you are released from the custody of the state. All you want to do is get back to normal life. You apply for jobs (you lost yours during the trial), but, mysteriously, you keep getting turned down, despite a clean record. The fact is, you may have successfully cleared your record, but you will never clear your name, because every trace of media where you are referred to as the suspect, the accused, or the alleged perpetrator remains online forever.

Every single article, video, tweet, Facebook post, and any other media remnant easily pulled up on the internet, will still be the top hit on a search engine, despite your innocence before the court. It’s an injustice that has no place in our system, but it doesn’t have to be this way.

A “Right to be Forgotten” law would require search engines like Google to remove any links to articles and publications that associate a person with a crime for which they’ve been found not guilty. The content is not destroyed – there would be no loss to the work of journalists who covered the initial charge – but by removing widely accessible links that pop up in simple searches, the law attempts to make it significantly more difficult for the average person on Google to discover a person’s affiliation with an accusation that was determined to be unfounded or untrue.

Right now, we attempt to “clear” a person's name by publishing an article of their acquittal, and consider the record corrected. But we all know this is not how modern media works. Depending on the situation, your charge and your mugshot gets thousands upon thousands of views, whereas your acquittal (months or years later) maybe gets a few hundred. There is no amount of record-correcting that can overpower a person’s affiliation with an accusation. Once we see a person’s name connected with a crime, even if we know they’ve been acquitted, it’s the accusation that sticks. Innocence be damned.

Now, there are certainly some people, and some crimes, to which this should not apply. Public figures (like elected officials or heads of major companies), should not receive this protection, in order to preserve the public’s access to information that may be in their interest. In addition, crimes like sexual assault, which have an abnormally low conviction rate and are often comparatively difficult to “prove” in the eyes of the court, could also be exempt. But there is simply no good reason that the average person accused and acquitted of a crime should carry the burden of guilt for the rest of their lives.

Don’t get it twisted, I’m all for the free flow of information, and preserving the public record as best as we can. But we have to recognize that the modern digital age presents a unique problem, where the ruling in the court of public opinion matters almost as much – if not more in some cases – as the one in criminal court.

For this legislation to have an impact, it would have to be passed on a federal level, with the power required to regulate large search engines and internet providers. I cannot push this legislation on the city level, but I urge my colleagues in Congress to take up this cause, and help preserve the innocence of so many. The old newspaper editor was right: the accusation is almost always front page news but you're lucky if the acquittal makes the paper at all. We need to uphold the power of innocence, or innocence itself ultimately loses its value.

***

City Council Member Justin Brannan represents parts of Brooklyn. On Twitter @JustinBrannan.

***

Have an op-ed idea or submission for Gotham Gazette? Email This email address is being protected from spambots. You need JavaScript enabled to view it.