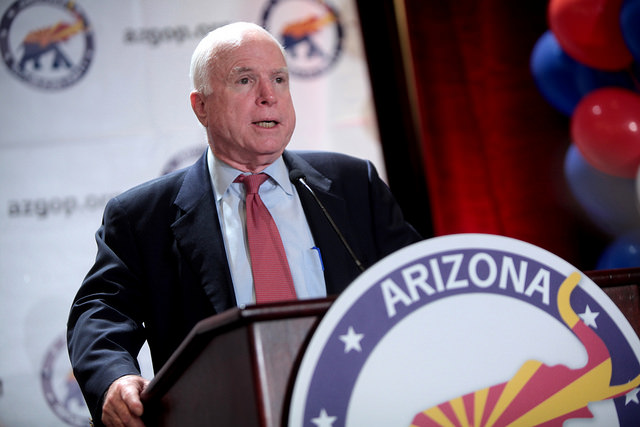

Remembering John McCain, Campaign Finance Reformer

Late Senator John McCain (photo: Gage Skidmore)

There are precious few genuine heroes left in public life in America. That’s why the passing of John McCain last weekend felt like such a huge loss for many of us whose lives are devoted to the practice of politics and government.

Despite his flaws, Senator McCain leaves behind a deep and unique imprint on American history. Among his most important legislative achievements was the enactment of the most significant national campaign finance reform measure since the post-Watergate years.

As a young press secretary to Congressional Rep. Christopher Shays (R-CT) in the late 1990s, I had the opportunity and privilege to work with Senator McCain and his staff as part of the legislative coalition fighting for reform on Capitol Hill. Though there were many good men and women whose efforts were necessary for success, there was no question who was leading the charge.

The issue of reform was a personal one for McCain. As one of the “Keating Five,” he was rebuked by the Senate for exercising poor judgment in meeting with bank regulators on behalf of Charles Keating, a long-time campaign donor and chair of a failed savings and loan institution. McCain described the incident as a low point in his career. He openly admitted his mistakes, apologized to his constituents, and began a relentless push to transform the campaign finance system.

The proposition that McCain and his colleagues advanced was a simple one: the same laws that applied to the way that candidates raise funds should apply to political parties and other campaign groups. No more corporate shakedowns for the party leaders—they would need to follow the same “hard money” restrictions as candidates. Interest groups trying to swing elections with campaign commercials disguised as “sham” issue ads (i.e. “Call Senator Smith and tell him to keep his hands off our guns”) would have to play by the same rules.

This was a stance that put him in direct conflict with the leaders of his party—Trent Lott and Mitch McConnell in the Senate, and Tom DeLay in the House—who collected the dough and held the purse strings. The McCain-Feingold legislation was a direct threat to their way of doing business.

Party leaders on both sides routinely approached corporate leaders for six-figure donations, often as they were considering Congressional action on their priorities. They distributed the proceeds to help their colleagues in close races. By withholding campaign funds, they could—and often did—exact retribution on those who stepped out of line.

The forces arrayed against the reform effort were powerful. Unlike today, there was no urgency from the grassroots in either party to address the corrosive power of money in politics.

Yet through the sheer force of personality and will, McCain pushed reform onto the national agenda. I recall long-serving members of Congress, as cynical as they come, whose faces would light up like school-kids in the presence of the senator from Arizona. Invariably, they would leave our coalition meetings giddy to follow him into battle.

The Bipartisan Campaign Reform Act (BCRA)--known as McCain-Feingold after the bill’s sponsors--took an extraordinary route to passage, one that seems no longer possible in today’s hyper-partisan environment. In the House, dozens of Republicans joined their Democratic colleagues to sign their names to a discharge petition that forced the bill onto the floor against the wishes of Speaker Dennis Hastert. In the Senate, 11 Republicans joined with the Democratic caucus to give the bill a filibuster-proof majority.

In taking on their party leadership, many of the moderate Republicans at the time were embarking on what could have been a political suicide mission. But McCain believed his party should succeed through the power of its ideas, not through the force of its fundraising efforts. By word and deed, he inspired his colleagues to follow his lead.

As we embark on a new conversation about campaign finance reform here in New York City, there are a few lessons to be drawn from the experience.

Achieving reform is about the art of the possible. It requires compromise and coalition-building. For all his legendary stubbornness and temper, McCain was an extraordinarily practical legislator. He was no purist—while protecting the soft-money ban at the core of his signature bill, he built his winning coalition by negotiating and embracing amendments offered by his colleagues. Some stand today as essential elements of every national campaign—if you are familiar with the phrase “I’m John Smith, and I approve this message,” you’ve felt the impact of McCain-Feingold.

The passage of McCain-Feingold stands as the high-water mark for reform in the post-Watergate era. While McCain himself moved on to other issues of great import and a second run for President, the federal campaign finance system rather quickly reverted to the norm. Under Chief Justice John Roberts, the Supreme Court has rolled back many the gains made by Congress under McCain’s leadership.

While the parties are still prohibited from cashing big corporate checks, McCutcheon expanded the parties’ ability to raise big money from wealthy individuals. And Citizens United eviscerated BCRA’s common-sense limits on fundraising for campaign advertising by independent groups. Unlimited funds from corporations, unions, and wealthy individuals are freely available to SuperPACs and political non-profits, many of which can evade even disclosure of their funding sources. With long-time reform opponent Mitch McConnell as majority leader of the Senate, efforts to reclaim that progress seem unlikely.

The rollback of McCain’s victories at the federal level makes it plain that reform is hard work. No lasting reform is a one-and-done effort. Successful reform takes patience, persistence, and constant vigilance. In New York City we have a campaign finance program that is the envy of reformers across the nation because we persist in the work of keeping the program strong. While the matching funds program has long helped candidates from diverse backgrounds run for office without relying on support from big business, unions, or wealthy individuals, questions about the role and impact of bundlers and large contributors in New York City’s system are proof that the work of perfecting reform is never done.

Indeed, the Campaign Finance Board is required to report after each election on the program’s impact on city elections, and issue recommendations to strengthen it. The Board’s report on the 2017 elections is out this week, and I urge you to take a look. The City Council has taken up many of these proposed reforms over the years, and this year’s Charter Revision Commission has advanced proposals that align with some of the Board’s recommendations. It takes many hands, working together, to transcend political divisions and to achieve lasting success.

Perhaps, in his passing and through our remembrances, John McCain can remind all Americans what is possible when our leaders are willing to put their allegiance to city, state, and country before their partisan or personal interest. Achieving reform doesn’t require heroism, but it does require sustained, selfless, and practical leadership.

***

Eric Friedman is Assistant Executive Director for Public Affairs, New York City Campaign Finance Board.

***

Have an op-ed idea or submission for Gotham Gazette? Email This email address is being protected from spambots. You need JavaScript enabled to view it.

Being Labeled the ‘Sheriff of Wall Street’ Isn't Enough

Letitia James, the author (photo: Gotham Gazette)

Wall Street malfeasance has had devastating consequences in New York State. It precipitated the foreclosure crisis, in which tens of thousands of families lost their homes, others faced an unrecovered loss in property values, and many jobs were lost. Ten years later, the Trump Administration and the Republican Congress are weakening oversight by federal agencies by watering down the Dodd-Frank Act and undermining the Consumer Finance Protection Bureau (CFPB).

Today, Wall Street securities valuations are, by all accounts, exceedingly high, corporate borrowing is excessive, and monetary policy still encourages risk. Fueled by predatory companies, student debt, and institutional greed, United States household debt has now grown to $13.39 trillion. Corporations are issuing debt again with fervor, and dark pools for trading securities still proliferate. We once again see flawed stock research, mortgage backed securities and other collateralized debt with sophisticated and troubling capital tranches. High-speed trading is prominent, and illegal front-running practices are still threats to our markets and society.

In this current booming economy, the Trump Administration has shown unsurprising short-sightedness and a remarkable short-term memory. The economy will inevitably ebb and flow, yet instead of bolstering safeguards, the federal government is rolling back the very protections and regulations established after the Great Recession. In taking aim at the protections--like the Volcker rule--contained in the Dodd-Frank Wall Street and Consumer Protection Act, the Republican Party is once again proving that it cares more about appeasing corporations than it does about protecting Americans from another financial crisis.

Fortunately, in New York, we have the most important prosecutorial power in the nation to stem malfeasance, protect our markets, and hold those who violate the law accountable: the Martin Act. The Martin Act grants investigatory and enforcement powers to the New York Attorney General, who is entrusted to enforce our state’s banking laws. Everyday, many millions of Americans rely on our state’s Attorney General to fully and judiciously use laws like the Martin Act to hold bad actors accountable and to prevent firms from defrauding the public.

As the next New York Attorney General, I will aggressively pursue these cases, and will use the Martin Act to the fullest extent possible.

Using the tools of the office, including subpoena power, I will investigate and watch over Wall Street. I will conduct data-driven investigations. I will bring cases, and seek injunctive relief to protect consumers, seek restitution for New Yorkers who have lost hard-earned money, and fight for wholesale policy changes.

I will stand up to the Trump Administration that seeks to pre-empt the Martin Act, protecting a critical power that fights Wall Street malfeasance. I will work collaboratively with the state Legislature to re-establish a six-year statute of limitations that recently was limited by the New York State Court of Appeals, ensuring that bad actors don’t go unpunished simply because the clock runs out. I will also work to increase criminal penalties for violations of the Martin Act, to mandate sentencing of perpetrators as larcenies of up to 25 years in prison. I will ensure that the Investor Protection Bureau has the necessary resources and support to expand.

Not since the time of Attorney General Jacob Javits in 1955, when criminal penalties were added by the Legislature, will there be a more committed champion of change. I will be the Attorney General conceived of in law, not just rhetoric.

For everyone on Wall Street to Main Street, let me be clear: as New York State Attorney General, I will use the considerable power of New York state laws to scrutinize those practices and industries that have benefited from deregulation under Trump, and those that are currently posing a significant threat to our economy. Unfettered greed that results in foreseeable losses that devastate the lives of ordinary and sometimes unwitting investors is actionable, and New Yorkers can count on me to take legal action.

***

Letitia “Tish” James is the New York City Public Advocate and a Democratic candidate for New York Attorney General. On Twitter @TishJames.

***

Have an op-ed idea or submission for Gotham Gazette? Email This email address is being protected from spambots. You need JavaScript enabled to view it.

Running for Attorney General, James Takes Strong Atlantic Yards Record Too Far

James at a 2007 press conference announcing a lawsuit challenging the environmental review of Atlantic Yards - she was not a plaintiff or attorney in the case (photo ©Jonathan Barkey)

A May Politico profile of New York City Public Advocate Letitia (Tish) James, the front-runner in the upcoming election for state Attorney General, noted that “she has occasionally shown a flair for exaggeration, which has periodically raised questions about her credibility.” Cited were statements about her age and her claim of credit for a New York Times series on homelessness.

Indeed, I’ve witnessed such exaggeration. Perhaps it’s carelessness, coupled with confidence in her undeniable charisma. Perhaps it relates to James’ alternative career choice of the ministry (as she once told an interviewer), in which parable can trump precision. But as James moves up the professional ladder, such hyperbole gets more hazardous, especially as she asks voters to make her the state’s top legal officer.

So it was surprising and dismaying to hear James during two recent appearances inflate her significant and often brave record opposing the Atlantic Yards project, the arena-plus-towers development announced in 2003 when she was representing the 35th City Council District in Brooklyn.

As the project’s leading political opponent, she asked tough questions at City Council hearings, sponsored an alternative plan for the Vanderbilt Yard, and stood up for residents threatened by eminent domain or denied promised construction jobs. She doesn’t need to overstate her role challenging the political firmament. (Her campaign, informed of examples to be outlined in this column, declined to comment on the record.)

James’ new posture seems politically expedient, since, as I wrote in May 2016, James actually has taken a softer stand in recent years, willing to call a reporter after being nudged by the original project developer, the politically powerful Forest City Ratner. (The project was in 2014 renamed Pacific Park.)

Taking Atlantic Yards to the U.S. Supreme Court?

At the August 15 Democratic attorney general candidate forum sponsored by Indivisible Harlem (at about 55:20 remaining on this video) James responded to a question about the city’s investigation of yeshivas said to be offering an inadequate secular education and got on a riff that segued to Atlantic Yards.

“Lastly, let me just say that I’m the only individual on this stage that’s actually taken a major developer all the way to the United States Supreme Court, and almost bankrupted him, is Letitia James. We took a developer [who wanted] to build a basketball arena for the worst team in the NBA, and engaged in foreclosing upon homes. And I’ll always remember, as a City Council member who looked in the eyes of someone who was a Holocaust survivor”—

The moderator intervened, reminding James that the question concerned yeshivas.

James was unbowed: “So it’s about yeshivas, and about a Holocaust survivor. And that Holocaust survivor said, ‘Tish, stand up and fight back.’ We’ll fight back and make sure yeshivas are educating individuals and we’re going to fight back against abuses by developers in the city of New York and the state of New York. And we’re going to stand up against corruption in the state of New York.”

Hold on. The federal eminent domain case, Goldstein v. Pataki, which James helped herald at an initial press conference, was rejected at the trial court and appellate court levels. Then the plaintiffs asked the Supreme Court to hear it; the Court refused, as it does most petitions. (A companion case was then filed in state court.)

So, while the case was brought to the Supreme Court, it wasn’t heard by the Supreme Court. More importantly, Council Member James as an individual played, at best, a supporting role. She was neither named plaintiff nor participating lawyer.

Checking a few details

Did that case “almost bankrupt” Forest City Ratner and developer Bruce Ratner? That’s a bit of a stretch, though Atlantic Yards -- conceived in optimistic times before the recession -- certainly caused major financial pain.

Also, neither Forest City Ratner nor Empire State Development, the state authority overseeing and shepherding the project, were "foreclosing on homes," or taking homes from borrowers in default. James would better have said that, with the threat of eminent domain, the developer was squeezing—and buying, with significant public dollars—people out of their homes.

A Holocaust story

What about that Holocaust survivor? James at least once has dubiously expanded that reference, as I wrote in September 2012, as the Barclays Center was opening, about a TV interview with James.

"The issue is really about standing up and advocating for your community...against the abuse of all is right,” she said. “This woman I know, and I'll always remember her, lived in footprint, she was a Holocaust survivor. She wanted to die in her home. She was 89 years old. She should've been allowed to die in her home and not suffer under the stress of being subject to eminent domain for a basketball arena."

I checked with two people who should know, and was told the elderly Holocaust survivor who was stressed by eminent domain was a commercial tenant, not a residential one. No one remembers -- and I asked again this week -- a residential tenant who was a Holocaust survivor.

Yes, an elderly woman in the footprint, Victoria Harmon, didn't want to move, and did end up dying at home, but she wasn’t a Holocaust survivor.

Repeating the eminent domain claim

This past Tuesday, during a Democratic attorney general candidate debate that aired on Manhattan Neighborhood Network, James brought up Atlantic Yards again.

“I took that [eminent domain] case all the way to the Supreme Court," she said at one point, soon amending the claim to “We."

As I wrote on Twitter, James deserves credit for promoting or participating in several Atlantic Yards cases, such as the environmental review case (in the photo at top), but not the claim as stated.

She was a named plaintiff in two lawsuits: one challenging the Metropolitan Transportation Authority’s willingness to relax a deal with developer Forest City Ratner, and another challenging the state’s 2009 re-approval of the project, which ultimately led a judge to criticize Empire State Development, the state authority overseeing the project, and to order a new environmental review.

Was my criticism, as one James supporter tweeted, “strangely nitpicky”? I don’t think so, especially if it’s part of a pattern.

A Prospect Park fable

James also exaggerated in her statement at a April 30 public hearing concerning a controversial two-tower project near Atlantic Terminal in Brooklyn called 80 Flatbush.

“So, we should not block the clock,” said James, referring to the widespread belief that the towers—one stretching 986 feet tall—would block views of the four-sided clock of the Williamsburgh Savings Bank tower, now known as One Hanson. (Neighborhood opponents say the clock will be blocked from the west; the environmental review says it won’t.)

“We should respect the lady, the Williamsburgh Bank building, which is an icon,” James continued. “And again, as someone who was born and raised in Brooklyn, when I would get lost in Prospect Park, I would always look to the Williamsburgh Bank building for direction and purpose and a sense of who I am and what I believe in.”

Really? The landmarked tower rises 512 feet. You can’t see near it from the biggest clearing (the Longmeadow) inside Prospect Park; that intersection is just too far away. The places where one might be lost, even in decades past, would further scotch sightlines. (By the way, if you walk up Flatbush Avenue a few blocks today and look northwest toward the bank, the clock is already blocked by a tower flanking the Barclays Center, 461 Dean.)

James had ample reasons to be wary of 80 Flatbush, notably what Assemblymember Jo Anne Simon and state Senator Velmanette Montgomery have called the request for an “unprecedented” tripling of allowable density. But James went beyond criticism to fable.

***

Norman Oder is a Brooklyn journalist who writes the watchdog blog Atlantic Yards/Pacific Park Report. On Twitter @AYReport.

***

Have an op-ed idea or submission for Gotham Gazette? Email This email address is being protected from spambots. You need JavaScript enabled to view it.