City Must Stop Using Incarcerated People as Revenue Source

(Michael Appleton/Mayoral Photography Office)

The City of New York, like many cities and states across the country, profits from people experiencing poverty who come into contact with the criminal justice system. New York imposes a plethora of fees on persons charged with and/or convicted of a crime or minor infraction, ranging from a fee to support the DNA Bank, to an incarceration fee, to a fee for parole or probation.

Among the most egregious of these fees involve phone calls in New York City jails. New York City reaps millions of dollars in profits from people who are in city jails and simply want to make a phone call.

Many of these people have not been convicted of a crime. Nearly 75% of people in New York City jails are held pretrial, many because they were arrested and cannot afford to make bail. Some are in jail serving short sentences for minor misdemeanor offenses. All just want to talk with family, friends, or their attorney.

On Monday, the City Council will take the next step in exploring the opportunity to end this predatory practice when it debates a bill, Intro. 0741, introduced by Speaker Corey Johnson. The bill would put a stop to the City’s practice of using the jail phone as a revenue center. Passing it would be a first and important step toward ending what is truly a tax on justice.

Over the last 30 years, as rates of arrest and incarceration skyrocketed across the country, jurisdictions struggled to pay for the bloated justice system. Cities, counties, and states increasingly tried to generate revenue by imposing fees on people, including children, arrested for and convicted of crimes. In California, the state adds $390 in fees to the $100 fine imposed for running a red light. In Washington State, courts impose an average of $1,347 on every criminal conviction. In New York, people convicted of felonies face mandatory fees of $300; for misdemeanor convictions, the fee is $175.

Although the criminal justice system is a vital government service meant to protect everyone’s public safety, more and more jurisdictions turned toward a “user-funded” system, unfairly demanding that some of the poorest Americans shoulder the burden.

Justice system fees disproportionately harm low-income people and their families who cannot afford to pay them. Communities of color are particularly devastated because they experience higher rates of poverty and over-policing in their communities. It is a burden that is often too heavy to bear. For the millions of people who cannot afford to pay them, outstanding fees trap them in the justice system for prolonged periods, entrenching poverty, exacerbating racial and ethnic disparities, and diminishing trust in government. And, because so many people cannot afford to pay them, criminal justice fees often generate less revenue than expected.

Some local and state governments have gone beyond simply trying to recoup costs through justice system fees and are trying to generate profits by imposing fees on people who are incarcerated, regardless of whether they have been convicted of any crime. In jurisdictions across the country, fees for “services” in jails and prisons (including exorbitant mark-ups on items for sale in the commissary) as well as fees for mail and “video” visitation are routinely imposed. New York City’s phone fee is a prime example of this unjust, discriminatory, and misguided policy.

Like all justice system fees, the phone fee particularly harms the city’s most vulnerable communities. It may also diminish public safety. When people in jail can’t afford to pay for phone calls, they can be cut off from contact with their families. Research shows that regular communication between incarcerated people and their loved ones correlates with lower recidivism and higher opportunity for successful re-entry to society.

We know the phone fee disproportionately harms people experiencing poverty and communities of color and may lead to higher recidivism rates. Yet, New York City government plans to extract millions of dollars next year from families who wish to stay in contact with their loved ones in City jails. Indeed, the mayor’s proposed budget anticipates that the Department of Corrections will collect nearly $6 million in profits from phone calls made by people incarcerated in city jails. But, budget negotiations between the de Blasio administration and the City Council have until the end of June to get it right.

The Council Speaker’s bill would stop the City from profiting from people who have already been targeted and trapped by a system that takes away freedom, dignity, and hope. It would help ensure that people who are incarcerated maintain critical community ties while they are in jail, increasing their opportunity for successful re-entry when they are released. It should be adopted by the Council and signed by the mayor.

***

Joanna Weiss is the Co-Director of the Fines and Fees Justice Center. Brandon J. Holmes is the #CLOSErikers Campaign Coordinator for JustLeadershipUSA. On Twitter @joannagweiss and @BJHolmes_NYC.

***

Have an op-ed idea or submission for Gotham Gazette? Email This email address is being protected from spambots. You need JavaScript enabled to view it.

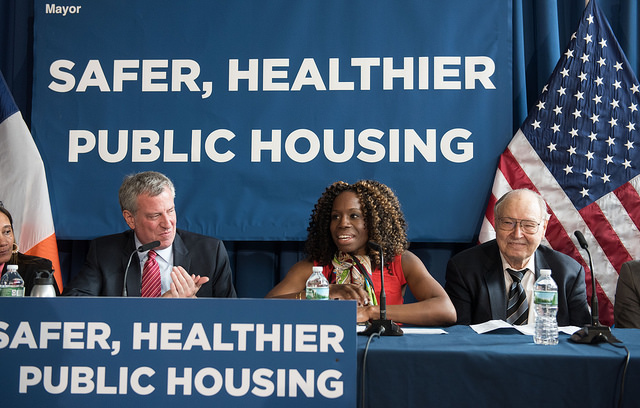

Shola Olatoye Did a Lot of Good for NYCHA

Outgoing NYCHA Chair Olatoye, center (photo: Michael Appleton/Mayor's Office)

As faith leaders in communities with large populations of NYCHA residents, we have witnessed the results of chronic disinvestment in public housing first-hand. NYCHA’s aging buildings are crumbling and many residents are worried about the health and safety of their children, elders, and neighbors.

Since 2001, NYCHA has been shortchanged $3 billion in federal operating and capital funding. NYCHA has been struggling to maintain and repair its aging housing stock for decades. And this is larger than New York City, public housing authorities all over the country are set up to fail, facing gutted budgets and regulatory barriers.

When she took her post as Chair and CEO of NYCHA, Shola Olatoye knew she needed to address these problems, so she worked with communities to make a plan. Under her leadership, we developed NextGeneration NYCHA, a 10-year plan to preserve and protect public housing for current residents as well as the next generation of New Yorkers and beyond. That plan became the road forward to safe, healthy, connected homes and communities for NYCHA residents.

Four years later, as NYCHA has strived to meet the NextGen goals, we have begun to see positive changes for the lives NYCHA residents. Under NextGen NYCHA, about 8,000 residents have been placed in jobs and 18,000 have been connected with services. NYCHA launched 14 new Youth Leadership Councils to give young people the tools they need to work with NYCHA leadership to help make policy decisions that impact the quality of life of NYCHA residents, and empower them to bring their perspective to the table.

We have also seen repair response times reduced from an average of 13 days down to four days and new “FlexOps” schedules that make frontline staff available for longer service hours. NYCHA has achieved more than $313 million in savings from NextGen initiatives and NYCHA has built up nearly 3 months of operating reserves. We are proud to have served on NYCHA’s Faith Leaders Committee and are grateful for Chair Olatoye’s leadership over the last four years.

To be clear, NYCHA’s problems didn’t come with the Chair and they certainly aren’t leaving with her. It is also now up to all of us to continue to fight for the 400,000 New Yorkers who call NYCHA home. We all bear some of the burden to fix this.

We are heartened to hear the commitment of Mayor de Blasio to the NextGeneration NYCHA plan, and hope the new Chair will continue to build upon this progress. We look forward to continuing to serve on NYCHA’s Faith Leaders Committee, supporting the incoming leadership, and working together for a brighter future.

***

Rev. Marc Rivera leads Primitive Christian Church and Rev. Al Cockfield leads God’s Battalion of Prayer Church.

***

Have an op-ed idea or submission for Gotham Gazette? Email This email address is being protected from spambots. You need JavaScript enabled to view it.

The Justice System Case for Radical Incrementalism

(photo: Ed Reed/Mayoral Photography Office)

Social media was full of despair as advocates bemoaned the failure of New York state government to approve bail reform legislation in the recently-passed budget. The push to eliminate cash bail brought together dozens of organizations and hundreds of concerned citizens to advance an important reform. This kind of mobilization is not atypical – advocacy campaigns tend to focus on passing legislation or electing officials.

Eliminating cash bail is a good idea, and over time, our bet is that it will end up succeeding in Albany. But we know from the Independent Commission on New York City Criminal Justice and Incarceration Reform chaired by former Chief Judge Jonathan Lippman that you don’t need to pass new legislation in order to transform the justice system. Indeed, the commission made the case that it is possible to reimagine criminal justice in New York City – including closing Rikers Island – without any new legislation whatsoever. In fact, this process is already underway.

The Mayor’s Office of Criminal Justice has just announced that the city's jail population is now less than 8,500 – down from a high of over 20,000 in the 1990s. This did not happen overnight. It also did not happen thanks to the passage of any single piece of legislation or the election of any single official.

Reducing incarceration in New York City took place over the course of multiple decades and mayoral administrations. It was a slow, incremental process, involving dozens, if not hundreds of decisions by different agencies and actors, the vast majority of which never made newspaper headlines. For example, in 1997, New York City’s criminal court judges released roughly 50 percent of defendants on their own recognizance pending trial, without setting bail. Today, this figure is closer to 70 percent. The implications of this shift in practice are enormous – it adds up to tens of thousands of defendants being given the chance to avoid the harms and abuses of Rikers Island.

Based on our work in New York and our recent examination of successful reform efforts across the country in Start Here, we argue for an approach to criminal justice reform that focuses on practice not politics. We believe that we need to transform the culture of our justice system – and that the best way to achieve this is by working directly with the police officers, prosecutors, judges, and correctional officials who staff our precincts, jails, and courts to help them change the way they do their jobs on a daily basis.

Many criminal justice reformers go over the heads of practitioners and speak directly to elected officials. Legislating change is an enormously tempting path to pursue. A successful bill in Albany or Washington can alter the course of government more or less overnight. At least that's the promise. In reality, things often don't pan out that way.

As Michael Lipsky pointed out more than a generation ago in Street-Level Bureaucracy, frontline staffers can sabotage or undermine any initiative that they do not believe in. That's why real criminal justice reform requires time – time to change the hearts and minds of the people who run the criminal justice system.

Let’s be real: it can be profoundly frustrating to take an incrementalist approach to reform. While there is much to celebrate in New York City, which now has the lowest rate of incarceration of any major American city to go along with dramatically reduced levels of crime, there is also much work still to be done. A trip to criminal court reveals that racial disparities are still very much with us. A visit to Rikers Island indicates that we have a long way to go before we can say that our system treats defendants with decency and dignity.

Here are three changes in practice that would go a long way toward making our justice system more fair and more effective.

First, police officers and prosecutors need to create off-ramps so that more low-level cases can be diverted out of the system entirely. Second, judges and court administrators need to do everything in their power to expedite case processing and avoid unnecessary delays – especially when defendants are being held in jail pretrial. And finally, elected officials need to make deeper investments in pretrial services and alternative sentencing programs so that judges have options beyond jail and nothing.

None of these fixes requires new laws to be passed -- just the active engagement of the people who run the justice system in New York City. The good news is that policymakers are aggressively pursuing all of the above.

New York City is a case study for the kind of justice reform that takes a long time to see to fruition – but it’s the kind of reform that is both durable and sustainable. The process is gradual; the results are nothing short of radical.

***

Greg Berman is the director of the Center for Court Innovation and co-author of Start Here: A Road Map to Reducing Incarceration (The New Press). Julian Adler is the director of policy and research at the Center for Court Innovation and co-author of Start Here.

***

Have an op-ed idea or submission for Gotham Gazette? Email This email address is being protected from spambots. You need JavaScript enabled to view it.