Making the City’s Vacant Land Work for the Public

(photo: Sofie Hecht/Gotham Gazette)

Last month, the city’s Department of Housing Preservation and Development (HPD) announced that it selected developers to build affordable housing on 87 city-owned vacant lots, which could produce almost 500 affordable homes. This came the day after Comptroller Scott Stringer released a report criticizing the city for moving slowly on developing such lots.

As New York City staggers through the unrelenting affordable housing, homelessness, and displacement crises this plan is a missed opportunity that we can not tolerate. The city has repeatedly squandered the most value asset - land - it has in fighting these crises. Instead of giving away these vacant lots, the city should keep them and create a public land trust.

New York City owns 1,125 vacant lots. For decades it has relied on an insider-favoring process that turns over vacant properties to private developers and some non-profit developers. That number doesn't include city-owned distressed properties, which is bound to spike as foreclosures are nearing great recession levels. In either case, the transfer comes with laughable requirements for (and definitions of) affordable housing.

This process is the result of a long retreat from the public ambition that defined New York City during its period of great growth in the first half of the 20th century. An activist city government - albeit one tainted by machine politics and systemic racism - built institutions that expanded the very idea of what public life could be and made modern New York City possible. That all ended in the 1970s and left subsequent leaders wary of ambitious public growth and reliant on powerfully connected private actors.

This must change. Our over-reliance on the private market has demonstrably failed the public interest and carries much of the blame for the mess we are in.

Using the community land trust model, the city should retain ownership of the land - removing it from the speculative market that drives up prices - and contract out development based on a fixed equity model that incentivizes construction while limiting costs. It would then directly own and manage this housing stock, guaranteeing that 100% of it is permanently affordable for low- and middle-income households.

Make no mistake, what I am suggesting is public housing. A new, 21st century form that avoids the previous century’s mistakes of massive public housing developments while retaining its public virtues.

Public housing, for all of its problems (thanks to a loss of $1 billion in federal funding since 2000, with more reductions on the way), is still the best vehicle for providing New Yorkers with sustainable affordable housing.

Despite its operational failures, NYCHA currently offers an average monthly rent of $509 to over 400,000 New Yorkers in 176,000 homes and has a waiting list of 257,000 families. Public housing works and we need more of it.

A public land trust that takes advantage of small-site development on vacant lots would work even better as a public housing model in today's economic, political, and social landscape. Instead of the discredited 'shotgun' approach of megablock development that destroyed existing communities while isolating its newly created ones, this approach would be a syringe-sized injection of affordability into existing communities and landscapes.

Neighbors would barely notice the physical changes while enjoying the practical protections of permanent affordability taking root across individual sites. Most of these lots are in distressed neighborhoods that are at high risk of displacement as speculative developers (many of them private equity firms) swoop in. The best, fastest way to address displacement in these neighborhoods is through public-owned land anchoring their development.

The community land trust model works, too. It has successfully provided permanent affordability across the United States for decades, notably in Burlington, Vermont (initially supported by then-mayor Bernie Sanders) and in Dudley Square in Boston (created by local residents who were granted eminent domain). Even here in New York City, the city's first trust, Cooper Square, has quietly managed hundreds of homes in the Lower East Side as a community land trust since 1994.

Speaking of Cooper Square, through its efforts along with the New Economy Project and NYCCLI, the community land trust model has finally started to get the attention it deserves in New York. Last year HPD and Community Enterprises announced $1.65 million in initial funding for the creation of new CLTs and training programs. Many elected officials like then-Borough President Scott Stringer, Council Members Donovan Richards and Margaret Chin, and Attorney General Eric Schneiderman have all worked to expand CLTs in the city.

These developments represent the chance for a fundamental shift in how to create permanent affordable housing in New York City. The land trust model does not rely on excessive tax-subsidies to private developers, flimsy definitions of affordability, or unenforceable protections for maintaining affordability over time. It is simple and sustainable. We should all be excited that the city finally sees this as a viable policy tool.

However, if Mayor de Blasio wants to deliver on his promise to build or protect 300,000 affordable housing units while also recommitting to public housing and NYCHA, he should take the next step by transferring the city’s many vacant lots into a public land trust.

We know the model works. The city knows the model works. Usually the hardest part is acquiring the land, but the city already has it. There is nothing to stop a public land trust from getting into the fight.

New York City was once capable of envisioning and delivering bold progress for the public good. We need this again, updated for the 21st century. The mayor has at the very least claimed this rhetoric and along the way tapped into a respondent audience in many corners of the city. Now it is time to act.

***

Peter Harrison is CEO/Co-founder of homeBody, a public benefit startup. On Twitter @PeteHarrisonNYC.

***

Have an op-ed idea or submission for Gotham Gazette? Email This email address is being protected from spambots. You need JavaScript enabled to view it.

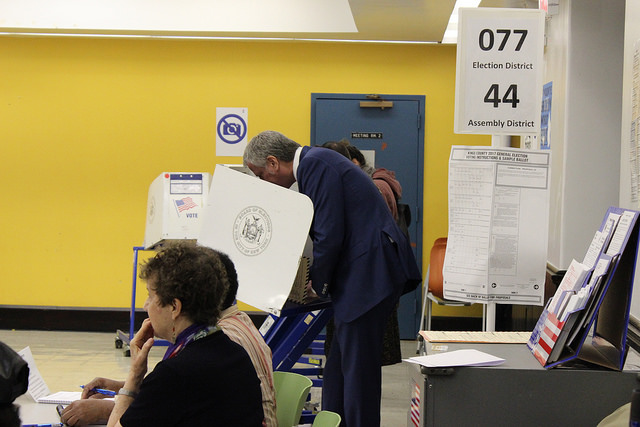

Can the De Blasio Administration Really Register 1.5 Million More Voters?

Mayor de Blasio voting (photo: Samar Khurshid/Gotham Gazette)

New York City Mayor Bill de Blasio recently announced a DemocracyNYC plan. One big goal: “to register 1.5 million New Yorkers to vote over the next four years.”

To make this work the mayor will create a new city leadership post: Chief Democracy Officer. How hard will it be for this new chief to meet the mayor’s goal?

Let’s do some rough math, based upon recent enrollment, census, and vital statistics data:

According to estimates in the most recent American Community Survey, there were 5,402,352 citizens of voting age in New York City in 2016 (plus or minus 22,325).

According to the state Board of Elections, in November of 2017 there were 5,053,842 registered voters in the city. That’s 93.5% of the eligible citizens.

Let’s make two initial assumptions to maximize the number of potential additional registrants among those of voting age now to make the CDO’s job more possible. First we’ll put aside reasons for disqualification other than age that would further reduce the number of those eligible but not registered (in prison or on parole for a felony, judged mentally incompetent by a court, voting elsewhere). Second, we’ll add that 22,325 to the estimate – that is, make the high side assumption of the number of age- eligible citizens while remaining within the statistical range of error.

That results in 370,835 citizens who are of voting age now and not registered.

Additionally, there are about 372,000 teenagers in New York City who will reach the age of 18 in the next four years. Of all people in the city over the age of 18, about four in five (80.5%) are citizens. The percentage of citizens among younger people, many born here of immigrant parents, is likely higher. They are not all citizens, but again let’s count more rather than fewer as likely to be eligible to register to vote: 9 in 10 of them. That would be 334,800.

That brings the available target total of potential new registrants to 705,635.

People from elsewhere in the country or living abroad (but not new immigrants) will move into and out of the city during the mayor’s second term. For now let’s just consider those moving in. Some will be children. Some won’t be citizens. A high side assumption from past experience of the number who can be registered: 200,000.

That brings us to 905,635 potential registrants.

Uh oh. We are 594,365 short.

Of course there are all those people who move within the city. They change their addresses. They need to re-register. Maybe the mayor meant to include them; he did not say the Chief Democracy Officer would have to find “new” registrants. So let’s give him the benefit of the doubt. Again we have to watch out for kids, non-citizens, and those already included in our count as not registered. Estimating from federal statistics on people moving annually within and between counties for 2011-2015, it looks like 483,000 is a reasonable number.

Still not there: 1,388,022 (OK, though, we’re getting within shouting distance). To meet the mayor’s goal the Chief Democracy Officer must find about 112,000 more people eligible to register in the next four years, and register them all. Where?

But wait a minute, that’s just the additions. How about the subtractions?

The Empire Center and others have noted that New York City’s population continues to grow every year because immigrants from abroad outnumber the many already living here who are leaving. Less noticed, most of those leaving are voters or vote-eligible, while those who are arriving are non-citizens. A conservative estimate is that 189,000 actual or potential registrants will move out of the city over the next four years.

Finally, there’s mortality. About 212,000 New Yorkers will die during Mayor de Blasio’s second term, more than 95% of whom are voting age. Of course, some - probably a smaller portion than for the city population as a whole - will be non-citizens. A reasonable, conservative estimate is that death will reduce New York City’s potential electorate by 171,000.

One-hundred-eighty-nine thousand plus 171,000 equals 360,000. Departure and mortality will reduce the city’s potential electorate in the next four years by about 6.5%.

Implications:

-Registering 1.5 million people to vote in New York City over the next four years is an impossible dream.

-Registering all of the age-eligible citizens now in the city won’t significantly expand the current electorate; it will keep it about the same size.

-The largest pool of potential registrants during Mayor de Blasio’s second term is comprised of people living in the city who are already registered, but changed their addresses.

-It would be truly extraordinary if the city’s voting roles grew by half-a-million registrants in the next four years.

The bottom line: If I were asked to be the new Chief Democracy Officer, the first thing I’d do is some serious counting. Then I’d call the mayor, to renegotiate the voter registration goal.

***

Gerald Benjamin is Director of The Benjamin Center at SUNY New Paltz.

***

Have an op-ed idea or submission for Gotham Gazette? Email This email address is being protected from spambots. You need JavaScript enabled to view it.

Expanding Immigrant Access to Health Care in New York

(photo: Kevin P. Coughlin/Governor's Office)

In January of 2017, after living in this country for 17 years, I was able to access health insurance for the first time in my life. I became eligible as a new graduate studentl at NYU, which had a Student Health Insurance Plan—and, because in New York, DACA (Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals) recipients were eligible for health insurance.

Now, when I am ill or in need of a checkup, uncertainty and stress are no longer part of the equation. When I feel sick, I no longer need to try to force my body into thinking I’m not sick or treat myself with Tylenol or Theraflu. Instead, I can see a doctor, get the prescription I need, and recover quickly.

Having access to high-quality health care in the past year has lifted an enormous burden from my shoulders. I used to feel anxious and scared every time I started to catch a cold. Now, each time I find myself at the Student Health Center since then, I feel gratitude and relief.

But now, as President Donald Trump’s attacks on immigrants escalate, health care access is in jeopardy again for Dreamers like me, as well as immigrants with Temporary Protected Status (TPS).

New York has long led the way in providing more expansive health care access than the federal government and most states. In Florida, where I went to college, I could not get health insurance. Earlier this year, Dreamers in New York received good news when Governor Cuomo announced that income-eligible DACA beneficiaries would continue to be eligible for state-funded Medicaid. This was an important step forward for the immigrant community and for health care for all in New York.

But the governor’s announcement does not mean that all Dreamers and immigrants will have access to health care. We need further action to ensure that all Dreamers and TPS holders have access to health insurance.

For immigrant youth like me, and young people across the state more generally, the solution is to pass legislation to increase the upper age limit of the Child Health Plus (CHP) Program from 19 to 29.

CHP was founded on the fundamental truth that health care is a human right. The program honors this principle by providing comprehensive health care services to uninsured young people not eligible for Medicaid or Marketplace coverage. For a mere .5% of the state’s annual budget, Governor Cuomo and the Legislature could expand CHP in this way to increase access to nearly 100,000 more young adults who would be newly eligible for high-quality coverage, since they have been aging out of CHP when they turn 19.

Additionally, with Trump acting to terminate TPS for countries like El Salvador and Haiti, hundreds of thousands of current TPS holders are at risk of losing legal status. In New York, this will put tens of thousands more in jeopardy of losing access to health care, in addition to potentially facing deportation.

New York State must take measures to ensure that TPS holders maintain their health coverage regardless of the reckless—and, frankly, racist—policies from Washington. First, the State must pass legislation to ensure TPS recipients remain eligible for Medicaid, even if they are stripped of their protection. Second, New York should create a state-funded Essential Plan for all New Yorkers who earn up to 200% of the federal poverty level, regardless of immigration status. This plan would be of particular urgency for immigrants who will be losing their TPS and thus, their current health insurance.

These policies offer a clear path for New York to lead on immigrant health care access. That’s why immigrant-led organizations like Make the Road New York (MRNY), which has included the policies as part of their statewide Respect and Dignity for All Platform, and the Coverage for All Coalition are lobbying legislators and the governor to adopt them. In fact, more than 500 MRNY members will be rallying and talking to legislators in Albany today -- Tuesday, March 6 -- about this issue as a central part of their 2018 agenda.

Day in, and day out, immigrants build this country. We are the ones who cook your food, care for your kids, stock your shelves, pick your vegetables, mow your lawn, and clean your house. We graduate in the top percentile of our classes, pay for our own education, serve our communities, and make lasting contributions to the beautiful tapestry of American culture.

Like all Americans, and all New Yorkers, we deserve access to health care—not as a privilege, but as a right.

New York has led the way before on health care access and standing up for immigrants. This legislative session, it’s time for Governor Cuomo and the Legislature to renew that commitment by adopting further measures to protect immigrants like me.

The Trump administration doesn’t want immigrants like me to have access to health care. We need New York to have our backs.

***

Lucas Lopes is a Master of Public Administration student at NYU’s Robert F. Wagner Graduate School of Public Service.

***

Have an op-ed idea or submission for Gotham Gazette? Email This email address is being protected from spambots. You need JavaScript enabled to view it.