Open Data Promises New Era of Transparent Government, When Will It Arrive?

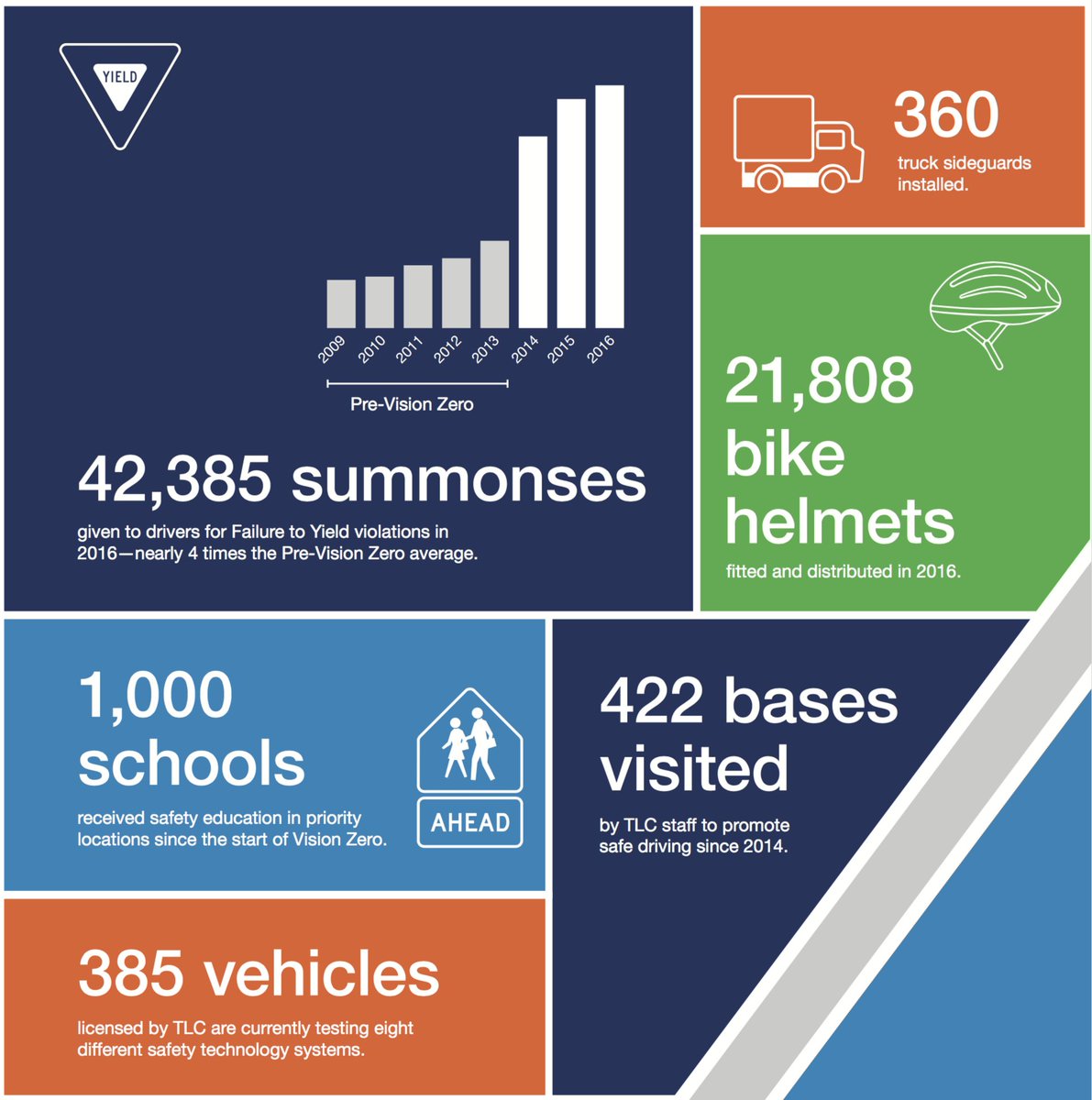

Vision Zero data (photo: @NYCMayor)

New York has had some issues when it comes to ethics and transparency in government, to say the least.

Whether it is the more than 30 politicians that have been convicted of corruption-related offenses, or countless challenges with getting public records from government at every level, it’s not hard to see that New York has a long way to go in becoming ethical, transparent, and accessible.

It will be a long road to repairing this mess. One concept that has the potential to be a huge help is Open Data.

Open data policies come in different shapes and sizes, but they all aim to take advantage of the digital age by posting data collected and maintained by government agencies to a public online portal. This provides citizens and watchdogs with easier access to information, and helps government agencies gain valuable insight into how they are performing.

It also reduces how often formal records requests must be filed under the Freedom of Information Law. For citizens, filing these requests can be difficult to manage, and potentially require costly lawsuits to see through. That’s not an option for many New Yorkers. Just think of the parents who recently protested the city Department of Education’s awful response time when they asked for records.

On the bright side, New York City’s Open Data plan is setting an example worth following for governments across the state.

The city’s policy has been in effect since March 2012, when Mayor Michael Bloomberg signed Local Law 11 of 2012 “to make City data available online using open standards.” City agencies’ public data sets must be posted on a single web portal by the end of 2018, with many sets already up and certain benchmarks along the way.

This legislation made New York City a leader in the open data movement, but the city has hit bumps in the road in implementing it.

Agencies were first required to self-submit plans showing when they would publicly release data. This was thankfully bolstered by packages of amendments added in 2015 and 2016. These amendments required more timely responses to public requests for new data sets.

More significantly, they demanded that agencies review FOIL requests asking for data to see if they involved new public data sets that could be published. This may sound complicated, but it’s a very commonsense ‘if one person is asking a question, somebody else is thinking it too’ type of policy. It is a built-in way to constantly expand the data available to the public.

The Mayor’s Office of Data Analytics (MODA) examines three agencies each year to verify that all public data sets have been disclosed. This is nice, but operates at a snail’s pace.

Many agencies are still delinquent in their reporting. With 92 participating agencies, it’s clear that MODA’s examination of just three per year will not guarantee all 92 comply by the December 2018 deadline. It’s one thing to promise, but New Yorkers need to see government deliver.

The bottom-line is positive, though. The City’s Open Data Portal received an average of 140,000 monthly hits from 2016 to 2017. There is a clear demand for transparency, and people using the system can hold lagging agencies accountable.

The City’s leadership on this issue has also gained a few followers.

Recently, the City of Syracuse launched its open data portal. Currently, the portal houses data about neighborhoods, housing, infrastructure, and lead risks. The city is requesting public input on what data should be added.

New York State enacted a similar open data policy in 2013, when Governor Cuomo signed Executive Order No. 95 establishing “an online Open Data Website for the collection and public dissemination of Publishable State data.”

However, the state’s plan is well behind New York City’s. Even the state’s trademark bragging tone cannot hide that its report shows incredibly important departments barely post anything. The state’s economic development arm, its Department of Education, and Government & Finance are all below 40 percent of records posted.

A look at specific departments finds a number that haven’t posted items recently. For example, the Dormitory Authority, which oversees Albany’s most notorious slush fund, the “State and Municipal Facilities Program” has not posted new data in over a year.

New Yorkers should be excited about Open Data’s potential to provide a window into what their governments are doing. They must get more involved as these policies evolve, and demand that deadlines and requirements are met – and that the state get caught up to speed.

***

Candice DiLavore is Reclaim New York Transparency Project Manager. On Twitter @cdilavorecdilavore & @ReclaimNewYork.

***

Have an op-ed idea or submission for Gotham Gazette? Email This email address is being protected from spambots. You need JavaScript enabled to view it.

We Need to Do More - Not Less - to Elect Women to Office

Sonia Ossorio, the author, is president of National Organization of Women – New York

Across the country, women are working to reclaim their power on the front lines of the resistance against the misogyny and xenophobia of the Trump administration. Yet when women decide to run for office themselves, they continue to face significant barriers — and in one local City Council race — those barriers have become starkly clear.

In the Bronx, Amanda Farias is running to represent District 18, which includes the neighborhoods of Soundview, Castle Hill, Parkchester, Clason Point and Harding Park. Born and raised in the Bronx, Amanda has made a career of serving her community. She brings extensive political experience running the City Council’s Women’s Caucus, working for Council Member Elizabeth Crowley, and leading participatory budgeting efforts for Council District 30. Amanda is exactly the kind of qualified, experienced and committed candidate we should be working to elevate and support.

But the Bronx County Democrats decided instead to back a candidate—Ruben Diaz Sr.— who fails to support the basic tenets of the Democratic Party and human rights, who seeks to put a woman’s decisions about her body into the hands of government, and who has demonstrated contempt for the LGBTQ community.

To add insult to injury, the Bronx County Democrats are trying to build roadblocks to prevent Amanda Farias from even getting on the ballot, leaving Bronx voters with fewer options. There’s nothing democratic about that.

Amanda gathered over six times the number of signatures required to be placed on the ballot, a testament to the desire of residents of the Bronx to see more qualified candidates run for office. Instead of embracing the opportunity for new voices, the Bronx County Democrats challenged the validity of her petitions. This cynical move makes their intentions all too clear: the Bronx County Democrats don’t just want their candidate to win. They want to prevent Amanda from even running. They don’t care if you have choices.

As the nation faces an onslaught of hate and bigotry across the country, the Bronx County Democrats’ petition challenge is especially chilling. In a time when the leader of our country dismissed bragging about sexual assault as “locker room talk,” when leaders of the current administration have threatened to defund the Violence Against Women Act (VAWA), and access to women’s healthcare is diminished, it is more important than ever to support strong, progressive leaders like Amanda Farias at the local level. And before we can even elect women, we need to make sure they get on the ballot.

There are currently only 13 women serving in the 51-seat City Council. Five are set to leave at the end of the year (four due to term limits)—all of whom are women of color. Unless we empower and support women to run and fill these seats, women’s representation in the Council will drop to an abysmal 16 percent.

No matter who is elected this fall to replace the departing Council members, one thing is clear. If we want to elect women, then we must be more proactive about giving women a platform. This isn’t just a Bronx problem—it’s a systemic issue for women who aspire to leadership positions from the corporate boardroom to national political office. But to change this culture and give women a path to the top, we must start locally.

This means cultivating women leaders from the start, organizing activist nights and holding events to create a network that amplifies women’s voices, similar to the work we do at the National Organization for Women – New York. This means being deliberate in recruiting women and diverse voices on community boards, by investing in campaigns early on, by not making women the last token choice when an opening comes up, and at the very least by not purposefully blocking the democratic process when women do pursue opportunities.

At the end of the day, voters should have more choices, not fewer, if we are going to move this country and this city forward. And it can and should start here in the Bronx.

***

Sonia Ossorio is President of the National Organization for Women – New York. On Twitter @NOW_NYC.

***

Have an op-ed idea or submission for Gotham Gazette? Email This email address is being protected from spambots. You need JavaScript enabled to view it.

Squadron Departure Spotlights Importance of County Committee

Former state Sen. Daniel Squadron (photo: @DanielSquadron)

Since Daniel Squadron announced his resignation from the New York State Senate last week, there has been a lot of conversation about “County Committee.” The vacancy in Squadron’s seat will be filled in a special election in November, and state law requires that the Democratic nominee for the seat be selected by the Democratic Party, as opposed to being decided in a primary election.

This means that, in all likelihood, the next State Senator for the 26th District, which includes parts of Brooklyn and Manhattan, will be chosen by a group of fewer than 500 people, since the Democratic nominee is so heavily favored in a general election.

This situation has a lot of people asking, “wait, what is the county committee and why do they get to decide?”

Each Election District in Manhattan (about one city block) elects two to four county committee members. These members are unpaid, political party posts, and have no official government role. They are expected to attend one meeting every two years to elect the County Party Chair and other leadership positions. Beyond this one biennial meeting, county committee members are generally only called upon when there is a vacancy.

In 2011, Assembly Member Jonathan Bing resigned from the State Assembly to take a job within the Cuomo administration. A special election was called and the County Committee members from the 73rd Assembly District were convened to choose the Democratic nominee. Dan Quart was selected, and he went on to win the special election with 63 percent of the vote.

More recently, Bill Perkins' victory in a City Council special election created a vacancy in the State Senate, which was filled by Brian Benjamin, who won the Democratic nomination by virtue of a county committee vote.

Adding to the confusion over county committee is that each county committee seat does not hold equal weight. The value of a county committee seat is determined by a formula based on how well the Democratic candidate for Governor performed in that particular election district. You may want to read that bit of random-seeming trivia one more time -- and think about how that weighted system can then affect the election of new state senators and Assembly members.

If this whole process seems onerous and confusing, that's because it is. There is no question that it benefits insiders and folks who have learned how to work the system. But it is the process we currently have, and the one in which we need to work to ensure that we elect the best candidates (while we also work to change election laws to make them more small-d democratic).

This year, the Four Freedoms Democratic Club, of which I am a member, aggressively recruited local Democrats to run for New York (Manhattan) County Committee. We reached out to community activists, local Indivisible chapters, and longtime Democratic club members. Our pitch was simple: if you’re frustrated with politics, or with the Democratic Party, then the best way to create change is at the grassroots level.

Anyone who is a registered Democrat in Manhattan can run for New York County Committee. To get on the ballot you simply need to collect signatures: five percent of the active registered Democrats in that particular election district, or anywhere from 15 to 50 signatures. This year, in Manhattan alone, there are over 40 contested county committee races, which means voters will have the chance to decide who represents them to the New York County Party.

There are those who believe it’s time to do away county committee votes for party nominees for state level seats, perhaps by shifting to the New York City system, which requires non-partisan special elections to fill vacancies. While that type of system seems preferable in theory, these types of special elections have absurdly low turnout. In that Harlem special election in which Bill Perkins was elected, for example, less than 10 percent of eligible voters cast a ballot. There is currently a bill in the New York State Senate that would implement such a system, sponsored somewhat ironically by now former Senator Squadron. In our current legislative culture, however, the chances of enacting any kind of meaningful election reform are slim to none.

In the meantime, we must continue to contend with the current system, and that means working to ensure that we are electing good people to county committee. I encourage anyone who is interested in this process to get involved in your local Democratic club. You can find more information about the Manhattan County Committee on the Manhattan Democrats’ website.

***

Kim Moscaritolo is a District Leader in the 76th Assembly District on Manhattan’s East Side. On Twitter @kimmosc.

***

Have an op-ed idea or submission for Gotham Gazette? Email This email address is being protected from spambots. You need JavaScript enabled to view it.