Save Our Waterfronts from Our Open Skies: New York & New Jersey

Manhattan from a helicopter (photo: Julia Vitullo-Martin, the author)

“I care passionately about our waterfront,” says Hoboken City Council Member Phil Cohen. “It’s the jewel of Hoboken, directly across from the Empire State Building. We fought so long and hard to get our world-class waterfront, endured epic battles, and now we have helicopters constantly buzzing us in our own park. Somehow the helicopters are always there.”

That’s because the most intrusive helicopters take off from Kearny or Linden in Cohen’s own state, fly up the Hudson, cross Manhattan in the 80s to hover over Central Park, fly down the East River, and then often joyride around the Empire State Building, Chelsea, and Lower Manhattan before heading out to hover over Governors Island and the Brooklyn waterfront, before returning to New Jersey, where they often circle the waterfronts of Jersey City and Hoboken.

And, of course, the helicopters routinely loiter around the Statue of Liberty to give maximum exposure for their clients’ Instagram accounts.

Sam Pesin, an activist designated the “Superhero of Liberty State Park” by InsiderNJ, has fought to the death one harmful invasion after another into Liberty State Park -- an amusement theme park in 1977, a commercial amphitheater in 1980, 8,000 luxury condo units in 1982, converting the historic rail road terminal into a doll museum in 1982, turning the park into a golf course in 1991, and again in1995, followed by another amphitheater proposal, a water park, a new marina, or even installing solar panels on the park’s recreation fields, plus a Formula One racetrack with viewing stands, writes Al Sullivan, and a high-end golf course. Pesin helped save Liberty State Park from all of this, only to see it inundated with low-flying helicopters, especially on weekend days and evenings. When the Sierra Club was filming “Wildlife of Liberty State Park,” for example, it had to stop repeatedly because the helicopter noise was too intrusive. Pesin is hopeful that the same coalition of community activists and environmentalists that halted other aggressions in the park can be mobilized against helicopters. He has a point. The coalition put together by Stop the Chop NY NJ includes both United States senators from New Jersey, U.S. Congressional Rep. Abio Sires, and mayors of Bayonne, Edgewater, Guttenberg, Hoboken, Jersey City, Weehawken, and several more.

Cohen and Pesin are voicing a parallel grievance to that published by former New York City Parks Commissioner Adrian Benepe and Governors Island Alliance executive director Merritt Birnbaum in the New York Times in 2016: “In recent years, New York City has invested over $2 billion in spectacular new waterfront parks. But that investment, and New Yorkers’ enjoyment of their parks and neighborhoods, is being ruined by an invasion of noisy, polluting tourist helicopters.”

Yet somehow, four years later, our waterfront parks are still being invaded, as is virtually every treasured landmark in our city.

Manhattan Borough President’s Data Analysis

For years constituent complaints about helicopter noise and pollution have made up the largest and often angriest set of complaints received by Manhattan Borough President Gale Brewer’s office. (“My biggest constituent issue on nice days,” Brewer said in 2012, when she represented the West Side in the City Council.) But this summer—in the midst of the covid lockdown—complaints unexpectedly shot up, coinciding with the unprecedented onslaught of tourist helicopters from New Jersey.

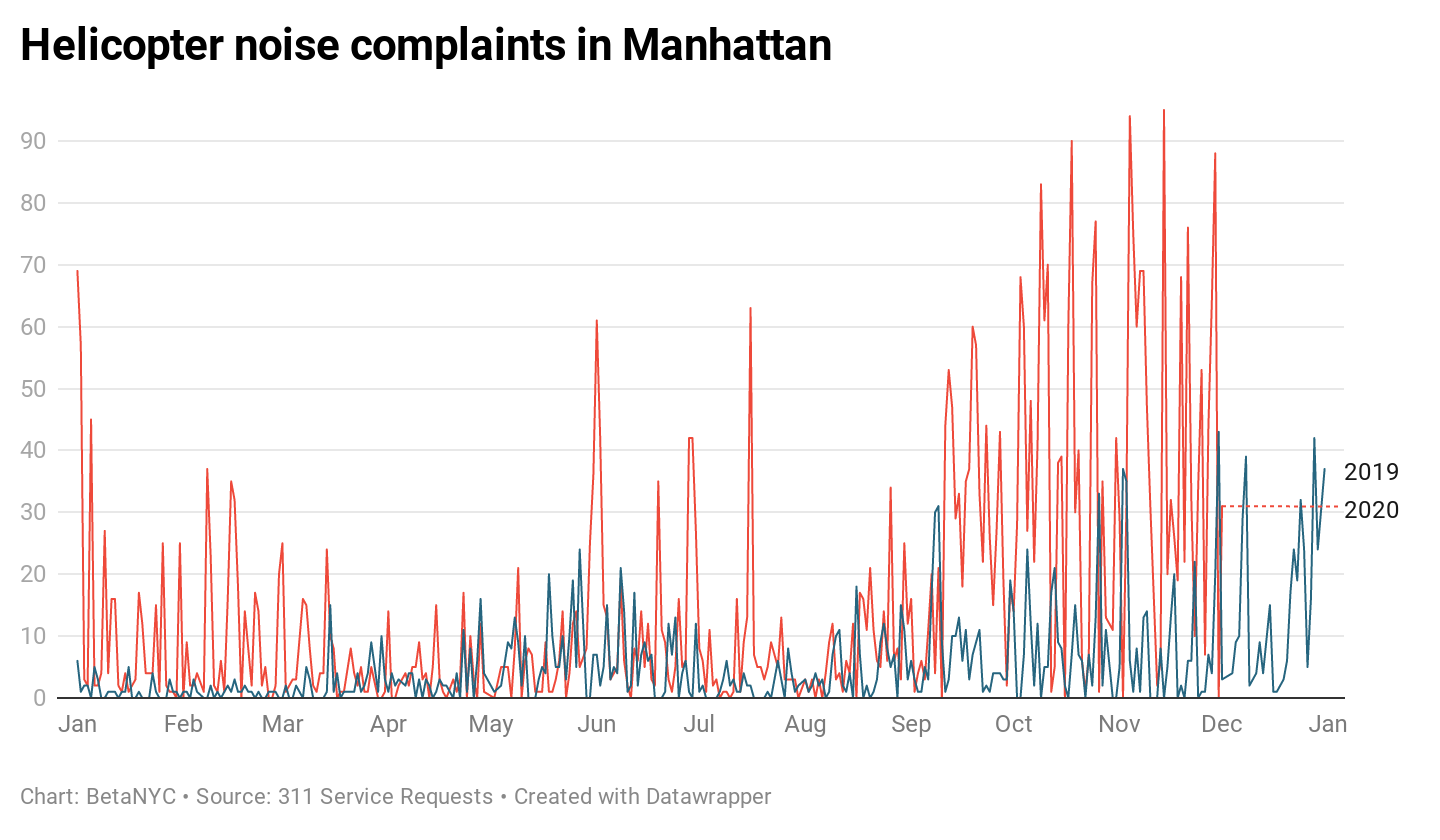

In response Brewer established a task force composed of officials, academics, and activists from both New York and New Jersey. Working from 311 data Zhi Keng He of BetaNYC showed the task force the dramatic pattern in Manhattan heli complaints, contrasting 2019’s relatively low numbers with this year’s record levels.

Yet while 2019’s complaints are low relative to this year, the increase began in September 2019, which saw 404 complaints, up to 729 in December. In 2020, complaints spiked in June—three months into the covid crisis—at 1,061, and hit 1,541 in November.

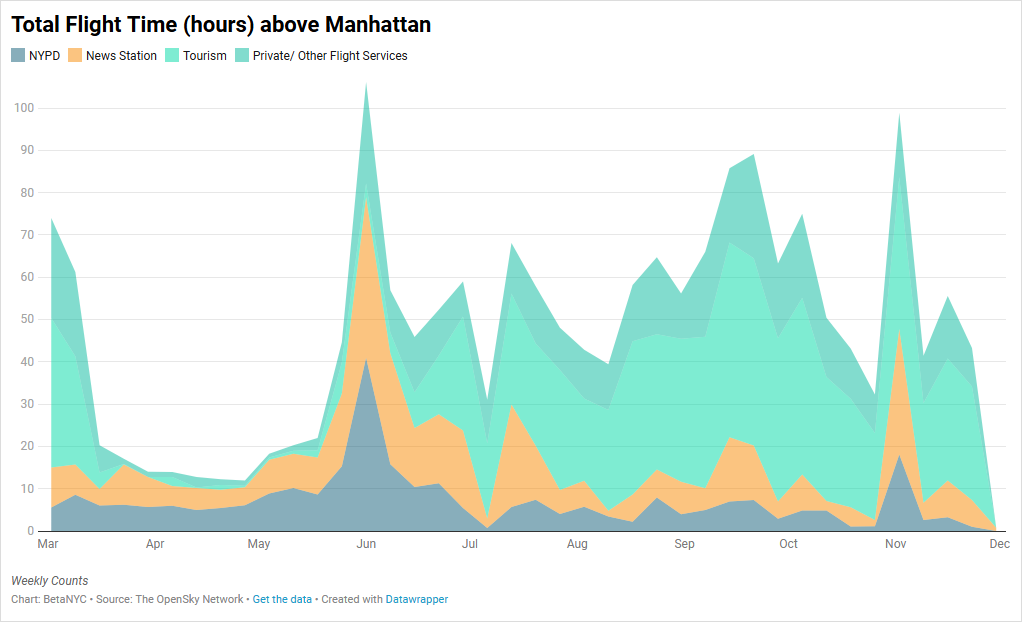

Citywide complaints follow a similar pattern, with the spike in June partly reflecting helicopter activity over protests, after which “Other” complaints took off.

The categorization into NYPD, News Gathering, and Other is by definition rough since 311 relies on the caller to report precisely. Those who use Flight Radar24 or Flight Aware are able to file their complaints accurately, but those without the apps will be guessing. In normal times, the NYPD is not the culprit. All of its seven helicopters are radar-tracked by air traffic control, and only two are assigned to routine patrol (as opposed to rescue), with the result that it is rare for the NYPD to deploy more than one helicopter at a time. Police pilots try to fly at high altitude “to avoid unnecessary disturbance to the public,” says the Deputy Commissioner for Public Information. And the NYPD does not block its signal.

One reason New Yorkers think that low-flying helicopters must be NYPD is that so many use search lights. “Of course that helicopter is NYPD,” said one of my neighbors, pointing straight up. “Who else would be allowed to direct a search light straight into our building for 15 minutes?”

Other culprits often mistaken for NYPD are news-gathering stations like PIX-11 News and ABC-7’s EyeWitness News, whose helis hover persistently—over New Year’s weekend they buzzed Manhattan for hours at a time. News helis fly in from New Jersey, circle the entire city repeatedly, often below 1,000 feet, and hang over neighborhoods and landmarks. How much of their activity is genuine news gathering?

What is to be done? Brewer has taken the first step, which is to set up a joint New York-New Jersey task force and begin the analysis. Those living on both sides of the Hudson might ask where this helicopter traffic is coming from and what can be done.

Kearny’s River Terminal Development

The Kearny Heliport (HHI Heliport) in New Jersey launches all of the doors-off FlyNYON tourism flights over New York and New Jersey, although some regular tours also fly from other heliports. (FlyNYON is the notorious sightseeing company whose doors-off tour crashed into the East River in March 2018, killing five passengers.) River Terminal Development is a subsidiary of the Hugo Neu Corporation, a family business for three generations of Neus based in New York. Hugo Neu Corporation describes itself as “a privately held company with deep experience in investing, building and managing businesses in recycling, real estate and related industries.” It prides itself on its Kearny Point development, which redeveloped a historic shipyard into “a diverse community of pioneering businesses,” somewhat similar to the Brooklyn Navy Yard.

Subsidiary RTC Properties, Inc. itself has 125 total employees across all of its locations and generates $20.76 million in sales. Requests for an interview have gone unanswered but clearly the owners of Kearny Heliport need to be involved in the public discussion of helicopters. Without their facility, the most egregious flights would not be made.

Helicopter Industry Reluctant to Help

Across the country the helicopter industry is organized into regional lobbying groups fighting hard against any further regulation or restriction on their activities. The Eastern Region Helicopter Council, which includes the New York metropolitan region, pledges its good citizenship: “For decades ERHC has worked with the elected officials and community leaders to reduce and eliminate impacts to the local communities.” Yet ERHC has done nothing to temper the behavior of its member, FlyNYON. This is in contrast to its active involvement in the helicopter hostilities of the Hamptons, where ERHC helped broker a modification in routes that temporarily moderated acrimony, ameliorating problems on the South Shore of Long Island while generating new ones on the North Shore.

While industry leaders privately express concern about the aggressive, low-flying flights harassing New York and New Jersey waterfronts and landmarks, virtually no industry spokesperson or executive seems willing to speak publicly—or even combat these companies privately.

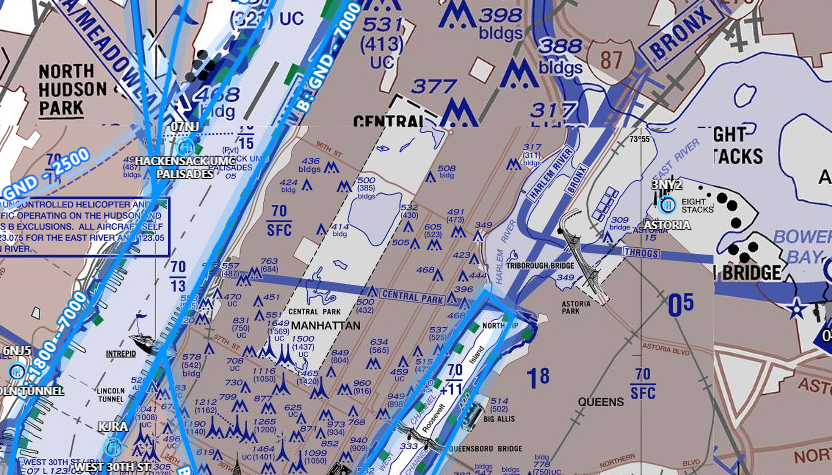

The one exception is Rob Wiesenthal, CEO of BLADE Urban Air Mobility, who says tersely of the doors-off tours, “They follow no rules and are dangerous, in my opinion.” Wiesenthal has been working with the LaGuardia tower and BLADE operators to eliminate, wherever possible, all overflight of Manhattan. The problem is that Central Park is an official route on helicopter charts and is the LGA tower’s preferred route across Manhattan. Wiesenthal says that except when mandated to follow the Central Park route, a BLADE flight will never fly over Manhattan.

The Federal Aviation Administration

Like all American airspace, New York’s skies are controlled by the FAA, which basically adheres to its “freedom to fly” principle treating the skies of America — including skies over densely populated cities — as highways. Robert Gottheim, District Director for Congressional Rep. Jerry Nadler, who has long been active on helicopter issues, says, “The FAA could change New York’s airspace entirely on its own if it chose. It could designate all the airspace to be controlled by LaGuardia, followed by no clearance. Or it could change the ceiling, essentially eliminating helicopters. Or just ban them all together. All of this is totally within their regulatory authority. They could do it all on their own without any input from Congress. People have a right to a high quality of life in their own residences. It’s not as if they bought a house by an airport and then started to complain. Manhattan isn’t supposed to be an airport."

The bad news is that FAA chief Steve Dickson, who has done nothing to ameliorate helicopter problems over New York’s crowded airspace, has announced that “he intends to stay on under the Biden administration, to fill out the remainder of his 5-year term ending in 2024,” according to the Wall Street Journal.

But the good news is that although the FAA is a classic clientele agency that views its mission as the promotion of the welfare of the industry it’s supposed to be regulating, it is nonetheless housed within the federal Department of Transportation, soon to be headed by Biden appointee Pete Buttigieg. Said Biden about the appointment: “This position stands at the nexus of so many of the interlocking challenges and opportunities ahead of us. Jobs, infrastructure, equity, and climate all come together at the DOT.” Gottheim is hopeful that the New York Congressional Delegation will be able to work successfully with Buttigieg, whose own presidential campaign had emphasized “high-quality, zero-emissions” mass transit for every city of over 100,000 residents.

Nadler and his congressional colleagues will be advocating hard for their HR 4880 bill prohibiting nonessential helicopters over New York. Gottheim says, “We hope that with a new administration headed by a Democratic president we can move this legislation.”

An Old Technique from NJ

In a previous incarnation of the great helicopter wars two elected New Jersey officials, U.S. Senator Robert Menendez and Congressional Rep. Albio Sires, worked with the FAA Eastern Regional Administrator in 2013 to reach an agreement reducing both the flight hours and the number of helicopters operating out of Paulus Hook Heliport. In other words, it can be done, even if it’s not done very often. Elected officials could work with, for example, Kearny and Linden to reduce flight hours and number of helicopters.

Similarly, despite their assurances that they can do nothing, New York City officials could regulate some of the most egregious helicopter behavior if they wished. Rob Wiesenthal points out that tour helicopters must sometimes land in Manhattan, that they often want to refuel here because it’s cheaper and faster, and some tour companies offer charters from New York City heliports. These activities open the door to local regulation. While the FAA says heliports can’t be selective about who is allowed to land, they can ban dangerous or objectionable behavior, such as failure to adhere to the 2016 agreement. Any New Yorkers regularly using the FlightRadar24 app knows that every week several helicopters joyride around New York after taking off from one of the three heliports.

Trump Temporary Flight Restrictions

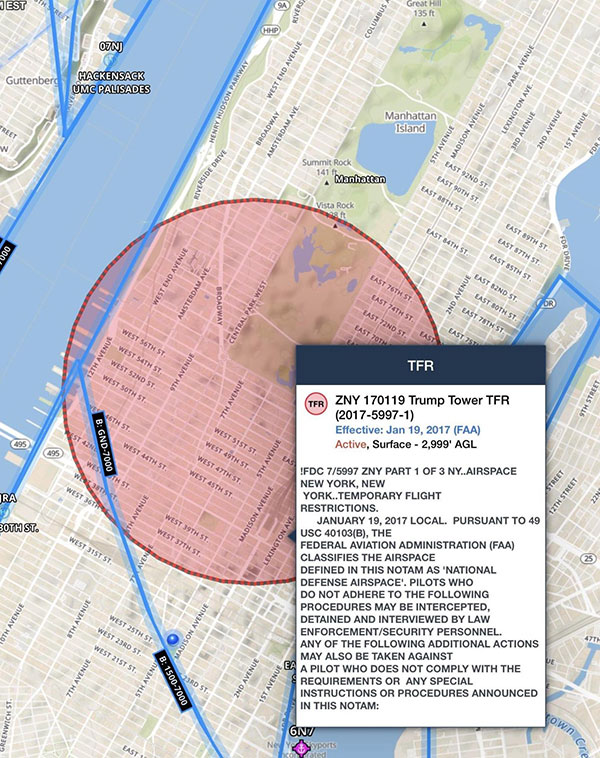

Because of the 2016 election of Donald Trump to the presidency the FAA drew a huge circle around Midtown’s Trump Tower, from 35th Street to roughly 80th Street and the Hudson to the East River, as a TFR zone or “National Defense Airspace.” This forced pilots north—thus the angry complaints to Brewer from her constituents above 80th Street and below 35th—and reinforced the use of Central Park as a highway. In theory the TFR should be modified with Trump’s exit, although there has been some chatter that restrictions may be retained if Trump asserts New York residency, even partial residency.

The 2021 Mayoral Race

While Mayor de Blasio has done nothing to ameliorate the helicopter onslaught, Stop the Chop and other activists intend to make the industry an important issue in the crowded 2021 mayoral race to succeed the term-limited de Blasio. Several candidates have been quick to designate climate change as a key issue, and of course a safe one, but none has yet said a word about helicopters. Why do we tolerate hundreds of aging, rattling, tour helicopters—flying for the most trivial of reasons—to burn fuel and produce substantial CO2 emissions while hovering noisily over our waterfront, parks, and landmarks?

The country will have a new president soon and New York will elect a new mayor in November. This is the moment for pushing hard politically. We already have a next president who has vowed to work collegially. Let’s get a mayor who knows how to reach across the Hudson, as Gale Brewer has done, and engage our neighbors in this fight to regain our waterfronts.

***

Julia Vitullo-Martin is a long-time editor and writer on cities. On Twitter @JuliaManhattan.

***

Have an op-ed idea or submission for Gotham Gazette? Email This email address is being protected from spambots. You need JavaScript enabled to view it.

It’s Time to Stop Repeating History: We Need Detailed Policing Plans from Mayoral Candidates

NYPD officers (photo: John McCarten/City Council)

As the new year begins and the 2021 mayoral primary unfolds, we need to know more about candidates’ plans for police. In 2020, New York City experienced enormous and persistent protests against police brutality, and the Department of Investigation released a report in December showing the many ways in which the NYPD’s response to those protests fell short. Meanwhile, gun violence in the city doubled compared to 2019, hitting low-income communities of color the hardest. We must demand that candidates for Mayor of New York City move past commissions, task forces, reports, and rhetoric to provide us with detailed plans that address policing and crime.

Although support for the Black Lives Matter movement this summer skyrocketed, New York City legislation has failed to meet the moment. New York State has increased law enforcement transparency and accountability by repealing Article 50-a of the New York Civil Rights Law, which had shielded police disciplinary records from public view, and has established a new Law Enforcement Misconduct Office in the New York State Attorney General’s Office, which will go into effect this April. While the city has taken big steps to regulate, for example, the use of police surveillance technology, local lawmakers have largely shied away from addressing issues related to use of force and police brutality.

The City Council outlawed “reckless” chokeholds many years after then-Police Commissioner Ray Kelly banned them in 1993 but they kept being used. The DOI report recommends expanding de-escalation and implicit bias training, echoing the de Blasio administration’s officer training courses announced in 2014. The NYPD’s proposed disciplinary matrix, released in August, simply consolidates existing guidance from the Patrol Guide and fails to assign termination as a presumptive penalty for excessive use of force, harrasment, sexual abuse, and other misconduct. If similar initiatives did not address the root causes of police brutality in the past, it is unclear why these actions will produce the meaningful reform this moment requires.

Demands for police reform reached their pinnacle this past summer. In contrast to many of New York City’s previous protests, the George Floyd protests began in familiar spots like Foley Square and Union Square but quickly spread to residential areas throughout the city like Astoria and Bay Ridge. And these protests drew enormous crowds: according to the DOI, in the afternoon of June 4 alone, there were nearly 15,000 protestors spread across the five boroughs. Also notable is just how many white New Yorkers showed solidarity with their neighbors of color on issues of police brutality.

The DOI report describes the NYPD’s handling of protests that were larger and more persistent than any other in New York City’s history. The report itself, however, is reminiscent of many of the police reform efforts of past mayoral administrations. Throughout the last century, city legislators have worked on police reform episodically, through task forces and commissions, and most of those efforts have fallen short. To ensure the DOI report makes a real impact, we need the candidates for mayor to be clear about their plans for meaningful police reform.

And we need them to show how they would provide a real break from repeating history yet again.

In 1935, Mayor La Guardia’s Commission on the Conditions of Harlem recommended that the city discipline police officers who interfered with civilians based on private prejudices. No such change took place. In 1966, Mayor Lindsay delivered on one of his main campaign promises by adding four civilians to the Civilian Complaint Review Board. Within the year, however, the Police Benevolent Association mobilized a public referendum that reversed Lindsay’s action. The Knapp Commission of 1970 established a statewide Special Prosecutor’s Office for the criminal justice system, both to monitor district attorneys’ anti-corruption work and to conduct its own investigations. The office was disbanded in 1991.

The 1992 Mollen Commission exposed a culture of “loyalty over integrity.” In response, the NYPD changed some aspects of police recruitment and training, and three years later, via executive order, Mayor Giuliani created the NYC Commission to Combat Police Corruption. The Girgenti Report, released in 1993, effectively ended Mayor Dinkins’ mayoralty by showing how he mismanaged the Crown Heights riots. The report, however, did little to recommend improvements to the NYPD. Mayor Giuliani assembled and then made a point of ignoring his 1997 policing task force, which consisted of lawyers, community leaders, and members of the clergy. In 2013, after a federal judge found the NYPD’s use of stop-and-frisk unconstitutional, the City Council established an Office of the Inspector General for the NYPD, joining the CCRB and the Commission to Combat Police Corruption as a third layer of oversight to the police. Each agency has the power only to make recommendations to the NYPD, many of which are ignored.

Despite the various commissions, task forces, reports, and oversight agencies, however, Officer Daniel Pantaleo kept his job for five years after he used a chokehold to restrain and ultimately kill Eric Garner in July 2014. George Floyd’s similar cry – “I can’t breathe” – resonated with a city that has grappled with issues of police brutality and racial discrimination since its founding.

Rather than focus on the isolated episodes of looting in Soho and Midtown, officers kettled and arrested over 2,000 peaceful protestors, including legal observers, pepper sprayed elected officials, and beat up journalists. Although the NYPD’s use of firearms has plummeted at a remarkable rate – from 810 discharges in 1970 to 35 in 2018 – videos from the summer show that police aggression and brutality have persisted.

Attempts to meaningfully ‘defund the police’ failed this fiscal year. Although the NYPD’s budget for the current fiscal year (FY21) was reduced by millions of dollars (the mayor speciously tried to claim $1 billion) in response to public demands, reductions represented aspirational cuts in overtime, sleight-of-hand transfers to other departments, and a $450 million reduction in capital funding rather than a meaningful change in the NYPD’s footprint. The actual budget cuts were closer to the order of $120 million, and even that may not hold. In any case, defunding the police is no magic bullet, and we must listen to municipal leaders of color, many of whom oppose the ‘defund’ movement and believe that well-trained, ethical officers are essential to the safety of their communities.

One of the DOI report’s main recommendations is to teach officers to facilitate First Amendment expression rather than obstruct it. Doing so requires not simply new training, but a fundamental paradigm shift within the NYPD, starting with its leadership. It requires a change in how officers are briefed before attending protests and the tactics they are permitted to use. Alongside this recommendation, we need more ideas that push us to rethink the role police officers play in maintaining public safety. Council Member and City Comptroller candidate Brad Lander’s plan to relieve the NYPD of its traffic enforcement and crash investigation responsibilities is another such idea. Removing officers from schools is yet another.

These policy changes are not radical; they would simply enable officers to focus on the tasks that require a badge and a firearm rather than responding to situations where a police presence heightens tension and causes harm.

In the background, from April 2021, the State Attorney General’s Law Enforcement Misconduct Office will investigate police misconduct and determine the need for prosecution, disciplinary action, or further investigation. This new office may help ensure that, statewide, actions have consequences for officers who abuse their power.

The DOI report is only the beginning of a necessary conversation about police reform in our city, but on its own it is insufficient to bring about change. We must understand how our mayoral candidates plan to implement the recommendations of the DOI report, whom they will appoint for key roles including Police Commissioner, and how they envision making police reform a reality.

In addition, we need new ideas that rethink how the NYPD maintains public safety alongside a broader coalition of organizations and agencies. We can no longer afford to settle for the endless commissions, task forces, and empty rhetoric of the past.

***

Benjamin Heller is a graduate student at NYU’s Robert F. Wagner School of Public Service. On Twitter @BenjaminHeller0.

***

Have an op-ed idea or submission for Gotham Gazette? Email This email address is being protected from spambots. You need JavaScript enabled to view it.

Community Health Groups Must Be Part of New York City’s COVID-19 Reckoning

Community clinics must be reconsidered (photo: Ed Reed/Mayor's Office)

For generations, health care has been vastly different for the haves and have nots, and the COVID-19 pandemic has only increased the divide that was already so apparent to communities of color in New York.

Having symptoms of the virus myself in the early months I went to Lenox Hill hospital, farther from where I live because my local hospital was already filled with patients. Now, keep in mind, all private hospitals receive government funding, but their internal policies determine what it means to receive basic care. In my case all that meant was a COVID-19 test and a standard x-ray. Any additional testing I may need, including blood work and an electrocardiogram – standard even for basic check-ups – would have to be paid from my own wallet.

Like most Afro-Latinos, I had been listening to the news of how the death toll continued to rise in my community of Upper Manhattan, and was afraid I would become one of those numbers. I was pained, too, seeing immigrant neighbors not receive the care they need or getting wrong information. But this is not surprising for those of us who have worked in the healthcare system. There have been consistent cuts to funding for health-focused community-based organizations (CBOs), which have an incredible history of advocating for newly-arrived immigrants who are still adapting to a different culture as well as other residents of low-income communities and communities of color.

But the cuts that occurred on multiple levels of government forced many of these organizations to close. If more health-based CBOs were open when the coronavirus upended our lives, the people who live in zip codes where the pandemic hit hardest would have had more options to receive the medical care they needed and deserved, contact tracing could have been implemented from the start, and the information these residents needed to survive would have been accessible.

The CBOs that had their doors open in New York provided the best care they could, all while the demand for their services increased. So many of them, like the Commission on the Public's Health System, were able to jump-start volunteer efforts to help deliver meals and groceries, and to collaborate with houses of worship to provide remote services. They are still the go-to health care option for many. Most importantly, they have built relationships with their patients, which is their best chance for these men and women to get over the final hump of this health crisis.

With the distribution of a covid vaccine underway, one-third of Latinos and fewer than half of Black people recently surveyed said they would not take the medicine. CBOs are the ones that can ease people’s fears so they listen to the advice of health professionals. But they need the financial support to effectively treat these communities.

While larger health nonprofits have great people working for them, many still fall short of ensuring they can serve a diverse group of people. New Yorkers cannot afford to continue to have an antiquated safety net system that leaves out communities of color.

Even now, advocates struggle to stop budget cuts to Medicaid and the NYC Health + Hospital System. In the midst of this national pandemic, every state has to exercise autonomy. But for years, public and private sectors have invested millions on studies relating to health disparities in New York City, showing that the more money you have the better healthcare you will receive.

Before COVID-19, there were many studies showing a lack of services in key zip codes, but nothing was done to address it. Only now, when a vaccine is finally being distributed, are elected officials paying attention to the health disparities that have affected communities of color for decades, and money is being allocated to the tracing efforts necessary of infected New Yorkers who were already living below the poverty line.

No one can say that we are “all in this together” when so many people are continuously robbed of quality health care. When the coronavirus has been contained and we can finally get back to living a semblance of the lives we remember, changes to the way health care organizations are funded needs to be changed to ensure all communities have access to the care they need. Only then will we be able to ensure all New Yorkers can lead a healthy life and truly be ready for the next pandemic.

***

Miosotis Munoz is a proven community advocate and non-profit leader who has worked in the healthcare and education sectors, and for several elected officials in New York City for almost three decades. She resides in Upper Manhattan.

***

Have an op-ed idea or submission for Gotham Gazette? Email This email address is being protected from spambots. You need JavaScript enabled to view it.