Statements Aren’t Enough; We Must Center Racial Equity in the City Planning Process Now

(photo: Edwin J. Torres/Mayoral Photo Office)

This is a pivotal moment in our city. As the disparate impacts of COVID-19 and the vital urgency of the Black Lives Matter movement make clear, New York City government needs a fundamental course correction, one centered on racial equity and undoing the damage of decades and centuries of injustice. Though the need for reform stretches across all our institutions, those that decide our built-environment play an especially crucial role. These agencies must reckon with a legacy of practices that have perpetuated systemic racism, hurt quality of life, and denied opportunities to communities of color.

City planning and the land-use process serve as a reflection of our city’s values and priorities. If racial equity is truly a priority for our city then a cultural shift in planning is needed, beyond a single institution or the ULURP process, to address a stubborn developer-centric approach that privileges capital over community. At the heart of this culture shift is rebuilding trust with New Yorkers that have been hardest hit. City government cannot simply repackage its current approach of rezoning low-income communities of color in the name of equity. At this crucial moment in our city and country, we need to do better.

Centering racial equity in the planning process would mean ensuring an equitable distribution of resources and development city-wide. Decisions would be based on needs like infrastructure and challenges like climate change and the risks of displacement, instead of a transactional approach based on a community’s political power. It would mean moving away from an approach that sees adding units as the sole indicator of a successful housing policy, without taking into account displacement, community wealth building, or racial equity. It would mean supporting and approving community plans that address both local and city-wide goals, and learning to build trust in that process.

Taking a color blind approach to planning, as many of our agencies do today, is not enough. We may not be using the same explicitly racist tools of the past, but for many communities, the outcomes are the same. In the absence of explicit racial-equity priorities, white residents and white communities with more resources and connection to power will always benefit the most. As the primary drivers of planning in the city, both the New York City Department of City Planning and Economic Development Corporation acknowledged the importance of addressing these challenges. While the statements are a necessary first step, they are not enough on their own.

The good news is that some of our institutions are already taking initiative to actively address historical injustices. For example, the City Parks Department developed the Community Parks Initiative. Centered on equity, this process helped the agency identify historically underserved parks in poorer neighborhoods - using dedicated funding to build new parks, improve programming, and increase operations to bring meaningful changes to open space and surrounding communities. Similarly, the City Health Department launched its Race to Justice effort several years ago to examine how structural racism impacts its work, helping it to develop staff knowledge and skills, new policies, and to collaborate with communities through an anti-racist lens.

The City Department of Housing Preservation and Development has shown what a good community planning process can look like, by working collaboratively with the Edgemere community after Hurricane Sandy to develop a community plan with 60 recommended projects, many of which have been funded. And in 2017, two local laws (60 and 64) were passed requiring the city to develop an environmental justice plan, which when complete will advise agencies and city leaders on the steps needed to address the environmental burdens low-income communities of color across the city have had to face, including strategies to improve health equity and deliver opportunities to expand the green economy. These examples show that New York City government is already working to undo a history of racist planning policies, although in a piecemeal way. We need to build on this.

When low-income communities of color push back on city-led plans, they must be listened to, not dismissed as being anti-change. When neighborhoods come together to craft a community plan that centers their values, while still addressing city-wide goals, city government should help realize their plans. And on the flip side, wealthier and whiter neighborhoods must no longer be off-limits for the types of increased density and development the city has prioritized in low-income communities.

We can make this shift by implementing a comprehensive planning approach that centers racial equity. One that commits not just words, but scarce money, time, and technical resources to ensure our institutions work in collaboration with each other and the communities they serve to lessen and reverse the impacts of historical and structural racism. Let’s get to work.

***

Maulin Mehta is Senior Associate of State Programs and Advocacy at Regional Plan Association. Christopher Walters is Rezoning Technical Assistance Coordinator at Association for Neighborhood and Housing Development. Both organizations are members of the Thriving Communities Coalition.

***

Have an op-ed idea or submission for Gotham Gazette? Email This email address is being protected from spambots. You need JavaScript enabled to view it.

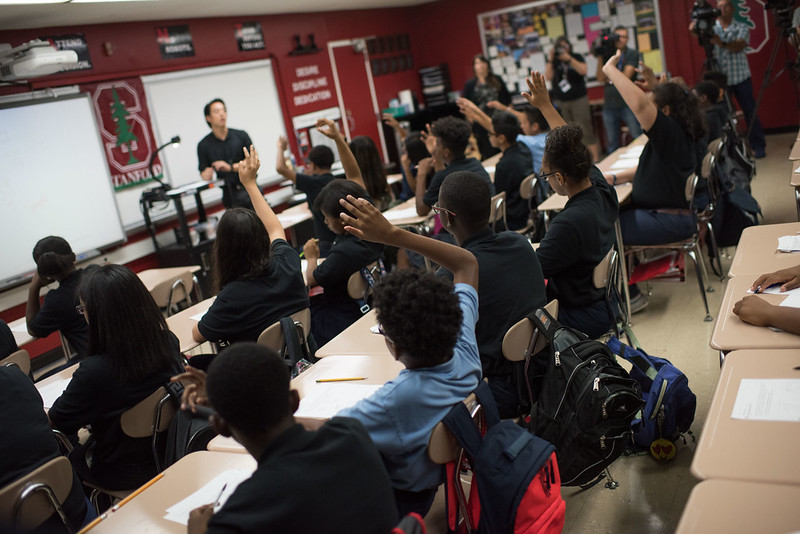

Save Our School Children: Give Them Philosophy

(photo: Michael Appleton/Mayoral Photography Office)

The question of how to resume our children’s education safely has understandably preoccupied parents, educators, and elected officials. And because the difference between the various models being proposed (‘blended’ vs fully remote) may well be the difference between life and death for a fellow human being, we need to rely on the best available science.

Yet the question of ‘how’ to restart school for the city’s 1.1 million public school students is not the only one we need to be asking. Two others that demand our attention are what they will learn and why. And because answers to these questions are essential to determining how well our children’s lives are to be lived, we need to turn to philosophy.

What students need to learn is how to think. That may sound obvious but what most students learn in school is not how to think but what to think. Instead of exercising their minds by exploring the many possible ways to be human, they quickly learn the value of knowing what is expected of them, what to repeat back, and what they need to do to pass the next test.

Rather than finding school to be a safe space for young minds to try out big ideas, too many students come to see school as a purgatory they must pass through before they take their pre-assigned role in a rigged game where success is measured by material gain. To allow such cynicism to take root is not to educate young souls but to impoverish them.

Learning how to think begins with the realization that the most interesting and important questions in life are not black and white but grey, not resolved with a google search or by asking Siri but are necessarily open-ended. That means not only that they can be answered in several, often incompatible ways, but that those various answers reliably raise a multitude of new questions of their own.

These include so-called ‘big questions’ such as “What is fair?,” “Do we have free will?,” and ‘What is truth?,” but quickly extend to what appear to be more pointed questions, such as “When is government coercion justified?,” “Is adequate housing a right?,” and “What is the purpose of an education?”

These are philosophical questions and they are the kind of questions that humans have been asking in one form or another for ages. The different answers that have been given at various times and places have shaped our history and have helped define our cultural identities. The answers we settle on give meaning to our lives by framing the choices we make concerning ourselves, our families, and our communities. The answers we try to live by determine how we deal with our failures and how we face our deaths. It is by learning how to think through these fundamental questions that humans learn how to live.

As every parent knows, philosophical questions come naturally to children. Still new to the world, the young can’t help but wonder who they are and who they might yet become. They are desperate to know what is possible, what is not, and why.

We need to encourage them in their quest to understand the human condition. Besides being intrinsically enjoyable, their philosophical investigations will improve their critical thinking, deepen their emotional intelligence, and lead them to be respectfully open-minded about diverse viewpoints. Making time for philosophy will also increase their understanding in math and reading.

Given the value and benefit of providing young minds the time and space to grow, we ought to be placing a philosopher-in-residence in every school to facilitate student’s intellectual journeys. We should be allowing them to ask if animals have rights, if robots can be persons, and whether prisons should be abolished. We should be encouraging them to articulate answers that make sense to them and to attentively listen to their classmates who do not agree.

But rather than make such discussions central to our children’s education, we too often dismiss their big questions as irrelevant and a distraction to the lessons we unreflectively think they need to learn. Little wonder that as children grow older they ask these important questions less and less.

And this points to the most important reason why we need philosophy in our schools, to ensure that when our children grow up they will be less like ourselves. Most people only encounter philosophy in college, if it all, which helps explain why so many adults don’t know how to think either. If we did, perhaps we would be leading happier, more fulfilling lives than we currently do.

If we learned to contemplate different alternatives and perspectives about how to live, then perhaps we would be able to converse respectfully with each other about matters on which we disagree. If as children we had been encouraged to think deeply about the difference between wants and needs, then perhaps New York City and its school system for which we are now responsible wouldn’t be as inequitable and painfully unjust as they are.

Our young people, certainly those of middle- and high-school age, are not so self-absorbed that they fail to realize that the way things have been is not only unacceptable, but that it is falling away. The arrival of the coronavirus and the tragic disruption that it has caused, coupled with a summer of social upheaval sparked by the killing of George Floyd and fueled by centuries of suffering and oppression, has forever altered the perspectives of this current generation of students. They want something better, something more just and more hopeful than the city and the lives they currently stand to inherit. We need to give them the tools to conceive what that something better might be, as well as the confidence to go forth and create it. Their lives depend on it.

***

Joseph S. Biehl, PhD, is the founder and executive director of the Gotham Philosophical Society and Young Philosophers of New York. On Twitter @jsbiehl.

***

Have an op-ed idea or submission for Gotham Gazette? Email This email address is being protected from spambots. You need JavaScript enabled to view it.

Homelessness, Housing, and the Upper West Side

(photo: John McCarten/City Council)

I spent a good portion of my childhood and adolescence around the intersection of West 79th and Amsterdam, whether it was with my parents or friends’ parents at Bagels & Co., or picking up snacks at the Duane Reade or Insomnia, or covertly eating non-kosher at Island Burgers. So it has been deeply saddening for me to see such a cornerstone of my neighborhood be turned into a rallying cry for reactionary hatred. The temporary sheltering of a few hundred homeless people in the Lucerne, the Belleclaire, and the Belnord is the least that the Upper West Side, one of the wealthiest neighborhoods in the Western Hemisphere, can do. Especially when the alternative is overcrowded, understaffed city shelters where COVID-19 could spread easily.

That’s the reality that seems to be lost on groups like Upper West Siders for Safer Streets, a Facebook page whose members have called for, among other things, smearing excrement on city benches to keep away homeless people and using fireworks to clear out homeless encampments: that we are living in extraordinary times. Just this weekend, America passed 5 million covid cases and 150,000 covid deaths. If otherwise-empty hotels can be used to help reduce covid vulnerability of existing shelters, then it should be done. With shelters recording a 60% higher rate of infection over the city, as Pablo Zevallos wrote last week, “social distancing...is a life-or-death matter for the homeless.”

Admittedly, plenty of my neighbors do understand this. They instead argue that they are being forced by the city to sacrifice their community for the sake of health. And to these people I have to ask: what sacrifice? According to NYPD data, crime on the Upper West Side is either flat or down year-over-year across all categories. By any metric, the Upper West Side remains the safest neighborhood in Manhattan. Just this weekend I passed by two Guardian Angels on the corner of my block, a block on which I have never, in my entire life, been witness to a crime. Contrary to the apparent beliefs of many members of the Safer Streets Facebook group, not every person of color you don’t recognize is homeless, nor are they committing a crime.

There is a growing sentiment among my neighbors, though, that being homeless is in-and-of-itself a crime. Whether people realize it or not, this is the sentiment behind worrying about, for example, public urination (real quick, give me the location of a 24-hour public restroom on the Upper West Side). My point here is not that public urination is a desirable outcome - of course it isn’t. It is, however, the natural consequence of having a very large population of homeless people and few public restrooms. Bear in mind, too, that New York is the only city in the country with a right-to-shelter law, which stipulates exactly what the name suggests: the city is required by law to house everyone. COVID-19 aside, there have never been enough shelters to fulfill this requirement, so the city has turned to hotels. Again - housing homeless people in hotels is not a desirable outcome, but it is the natural consequence of not having built enough housing.

And this is an area where our neighborhood has clearly failed. I’ve always found it funny that Mayor de Blasio is blamed for everything bad that happens on the Upper West Side when his housing policy has left our neighborhood virtually untouched. Since 2014, the city has constructed just one affordable building north of 62nd Street. This is not because of the high cost of housing on the Upper West Side. Aaron Carr, founder of the Housing Rights Initiative, pointed out that the city’s own report on affordable housing found that expensive markets are actually better for affordable housing construction. This way, private developers can more easily defray the cost of affordable units with more expensive, market-rate units. So why, then, has the city built so much affordable housing in lower-income neighborhoods like East Harlem and Bedford-Stuyvesant and nothing in higher-income neighborhoods like the Upper West Side? The Lucerne is the answer. As Carr put it: “The backlash against the hotels is part of a broader pattern of exclusion.” Upper West Siders do not want new housing, so no new housing has been built.

But there is no other way to resolve this crisis. Shelter is, quite literally, the most basic human need, and there is no other way to help homeless New Yorkers get their lives back on track. It is high time that neighborhoods like the Upper West Side, wealthy even by the standards of the richest city in America, contribute to ending our housing crisis. That’s why I’m an active member of Open New York, a group fighting to bring more housing to wealthy neighborhoods so that more people can afford to live in New York City.

We’re currently working to upzone SoHo, but the same arguments apply equally well to the Upper West Side. More housing in the wealthiest neighborhoods will create more funding for affordable housing, increase integration, and take displacement pressures off vulnerable, less-privileged areas of the city. We live in a neighborhood that millions of Americans can only dream of: good schools, safe streets, and beautiful parks, right in the heart of the economic engine of the world. Instead of building walls around what we are fortunate enough to have, we should open our doors and give others the chance to share in it.

***

Jonathan Lindenbaum is a lifelong Upper West Side resident and member of Open New York. On Twitter @urbaneurban.

***

Have an op-ed idea or submission for Gotham Gazette? Email This email address is being protected from spambots. You need JavaScript enabled to view it.