Toppling Statues, and Prisons

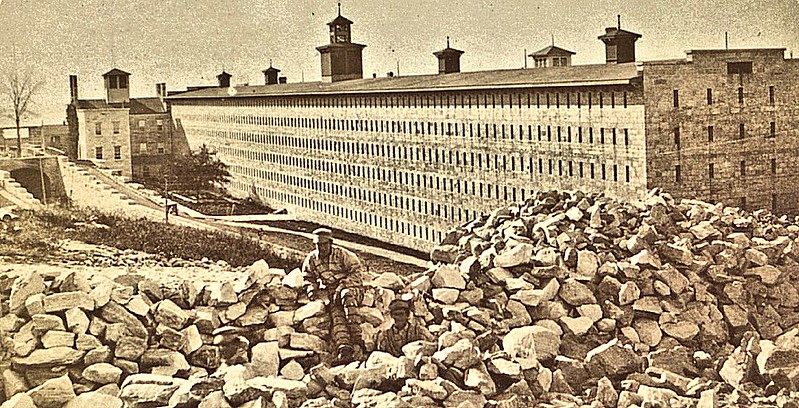

Sing Sing prison, 19th century (photo: New York Public Library)

Monuments of all kinds are facing renewed scrutiny as protesters, fueled by the police killing of Rayshard Brooks, George Floyd, Breonna Taylor, and others, have taken to the streets in more than 140 cities. Statues that glorify and venerate slavery and slaveholders are coming down, with or without governmental approval, across the country. The sight of these prominently displayed symbols of brutality, inhumanity, and state-sponsored racism tumbling down inspires hope that there may also be a long-overdue reckoning for the United States’ centuries of devotion to white supremacy.

Now is clearly the moment for all to examine the monuments that clutter the landscape – not only those that honor the racist deeds of the powerful men enshrined in their statues, but those built of impenetrable walls that continue to enslave tens of thousands of people. And while few thought, up until a few months ago, that hundreds of statues could ever be questioned, protested, and pulled down, so, too, should prisons – repugnant monuments in stone – now be subject to the same critical scrutiny.

Just as those who tear down statues understand the historical contexts in which they were built and persist, so too do prison abolitionists share a perspective – they teach that prisons are borne of a larger system with roots in slavery, and envision a path forward to a society where such institutions no longer exist. The abolitionists dare to imagine a time when – as with other monuments to atrocity – they come down, stone by stone, brick by brick.

‘Progressive’ New York is home to several of the country’s oldest and most brutal prisons.

Auburn prison was built in 1818. It is the site of the first execution by electric chair and the namesake of the "Auburn system," a practice that placed people in solitary confinement and required physical labor performed under complete silence. Any objections were met with a whipping.

Sing Sing prison was built in 1826 with cells measuring 7 feet deep by 3 feet-3 inches wide. The men inside were forced to mine the land and produced marble used in the construction of Grace Church in Manhattan, New York University, and the New York State Capitol and United States Treasury buildings. Six hundred and fourteen people have been executed in Sing Sing’s electric chair.

Clinton Dannemora was built in 1844. In 1887, 60-foot-high stone walls were added to the prison. Those walls still stand. It is sometimes called Little Siberia owing to the cold winters and the isolation of the upstate area where the prison sits. Originally, prisoners were used to supply labor to local mines. Nowadays, people inside New York prisons work a variety of tasks for an average of 65 cents an hour and their labor generates about $50 million in annual sales that goes mostly to local governments. Clinton is the largest maximum-security prison in New York, with a staff that includes about a thousand correction officers and supervisors.

New York, like many other states, built the majority of its prisons in rural regions far from the urban areas where so many of the incarcerated live. This reality exists up to the present: every prison in the state built since 1982 is in upstate New York. The proliferation of prisons in isolated, distressed rural areas that suffer from a lack of industry and jobs is due to their elected officials vigorously lobbying for prisons as economic saviors. The relationship between the decline of the upstate New York economy and the prison construction boom of the 1980s is unmistakable.

In many rural communities, the entire economy revolves around the local prison. Prisons offer jobs for relatively unskilled members of the community with no relevant training or experience. Rural towns in upstate New York employ hundreds of locals to oversee thousands of outsiders. Add to the mix the racial imbalance—predominantly, if not exclusively, white officers guarding predominantly Black and brown men—and the potential for abuse is as clear as the ugly images conjured up of plantations and slavery.

It is this upstate/city, white/black, guard/prisoner dynamic that leads to so many of the prison abuses that have been exposed over the years. Whether due to lack of familiarity, understanding, and trust, or racial animus, intolerance, indifference or neglect, the predictable results are systemic mistreatment. Discrimination in housing and job assignments and inadequate access to medical and mental health treatment are endemic. Fully revealed these days is the long-existing abuse of what are euphemistically called "special housing units" or "isolation cells"—in other words, rampant and prolonged solitary confinement for thousands of people.

While it may today seem impossible to literally bring down the prison walls, to attach a rope around the turrets and pull them down, much can be done. We can begin to dismantle from the inside out by freeing the innumerable people who remain incarcerated solely to satisfy the criminal legal system’s unquenchable thirst for punishment. Countless people of color in prison remain there solely because of racism and white supremacy, hastily dispatched by judges to serve life behind bars.

So much seems permanent in the American carceral system. The ancient upstate prisons stand with their imposing walls as unyielding fortresses. The people inside feel frozen in time, confined by a system that defines them solely and eternally by an act committed years before. It all feels impervious to change.

Yet few believed just a few months ago that scores of people would now be in the streets toppling visible symbols of oppression and reclaiming public space. Few thought there would ever be a serious conversation about defunding the police. Structural change in funding and priorities is on the immediate horizon. The current uprising calls for overarching reckoning and rectification. There is no reason its reach cannot be extended to prisons.

We can tear down a punitive system that values interminable punishment and holds no space for redemption. Newly constituted parole and clemency agencies must see people in prison for who they are and understand why they were incarcerated in the first place. Thousands of people can be immediately released as we begin to finally address the crisis of mass incarceration that has decimated families and communities of color. And eventually the walls of the prison just might come tumbling down.

***

Steven Zeidman is a professor of law at CUNY School of Law. On Twitter @SteveZeidman.

***

Have an op-ed idea or submission for Gotham Gazette? Email This email address is being protected from spambots. You need JavaScript enabled to view it.

One Essential, Concrete Step to Redress Environmental Racism in the South Bronx

Transforming the South Bronx (photo: Kevin P. Coughlin/Governor's Office)

Our country’s history has been fraught with issues that have disadvantaged communities of color, including unequal housing, education, health, food access, economic opportunity, and the chronic stresses of living with racial bias. Intertwined with these are a myriad of severe environmental justice issues.

Communities of color suffer disproportionately from air pollution from nearby waste facilities, industrial plants, and high bus and truck traffic on their thoroughfares.“Diesel trucks and diesel buses play a significant role in impacting the health of our communities negatively,” said Cecil Corbin-Mark of WE ACT for Environmental Justice. “For us, this is one of the ways in which environmental racism manifests itself.”

In New York, one of the hardest-hit communities is the Hunts Point section of the South Bronx.15,000 trucks a day transport products and service the Hunts Point food market, which sells food to the whole city. "Yet Hunts Point itself is a food desert,” New York State Senator Alessandra Biaggi points out. “Residents often do not have access to the fresh produce being distributed right in their neighborhood.”

Diesel trucks spew exhaust containing particulates, nitrogen oxides, and ozone, which damage public health. Exposure to them correlates with increased emergency room visits, hospital admissions, and premature death. It also correlates with higher mortality from coronavirus. The asthma rate among youth in the South Bronx is 13% -- almost twice the national average. Nationally, communities of color breathe 66% more air pollution from vehicles compared to predominantly white communities. To lower childhood asthma rates, cardiovascular disease, stroke, and lung cancer, pediatric health expert Dr. Philip J. Landrigan recommends replacing diesel buses and trucks with safer, non-polluting alternatives.

We know how to do that, and we should do it now. New high-performance natural gas-powered engines for medium- and heavy-duty trucks virtually eliminate the health-damaging pollutants in diesel exhaust and are widely available. They’re also much quieter than diesel engines, enabling residents to sleep better at night.

These engines can run on conventional compressed natural gas or, better yet, on renewable natural gas (RNG), made from the methane biogases emitted by decomposing food and other organic wastes. Instead of letting them escape into the air, where they trap heat and warm the climate, the biogases are captured and refined into RNG. According to the California Air Resources Board and Argonne National Labs, RNG is the lowest-carbon fuel available today. When made from organic wastes diverted from landfills, RNG also reduces the negative impacts on communities near those landfills.

Trucks equipped with these engines cost about $40,000 more than their diesel counterparts. But a new “Clean Trucks” program initiated by the New York City Department of Transportation is covering the incremental costs of gas/RNG-powered and electric trucks, so private and municipal truck fleets in New York can afford to switch from diesel to clean trucks. They will have no trouble procuring RNG to run them. Last year Clean Energy Fuels, the largest U.S. supplier of natural gas, opened a refueling station in Hunts Point that sells RNG exclusively. It also announced last year that by 2025 it will phase out fossil gas and supply customers with RNG only. Since RNG is ultra-low carbon, fleets that adopt it will meet or even exceed New York and Paris Accord emissions targets, not by 2050, but overnight.

Clean trucks won’t solve all environmental justice problems. But for the South Bronx and other communities disproportionately impacted by diesel haulers, they’re an important step toward justice. The trucks, fuel, and financing are all available and ready to go. What’s needed now is the political will to use them. That’s a matter of principle, a question of what kind of country we want to live in.

We have a lot of work to do to build a society where justice for all extends to communities of color. Part of that work is eliminating discriminatory exposure to pollutants, and making sure environmental justice communities are first in line to get the benefits of technologies like clean trucks and RNG.

***

Joanna Underwood is founder and trustee of the NGO Energy Vision. On Twitter @energy_vision.

***

Have an op-ed idea or submission for Gotham Gazette? Email This email address is being protected from spambots. You need JavaScript enabled to view it.

The Covid Crisis Has Made It Additionally Clear: It’s Time to End School Admissions Screens in New York City

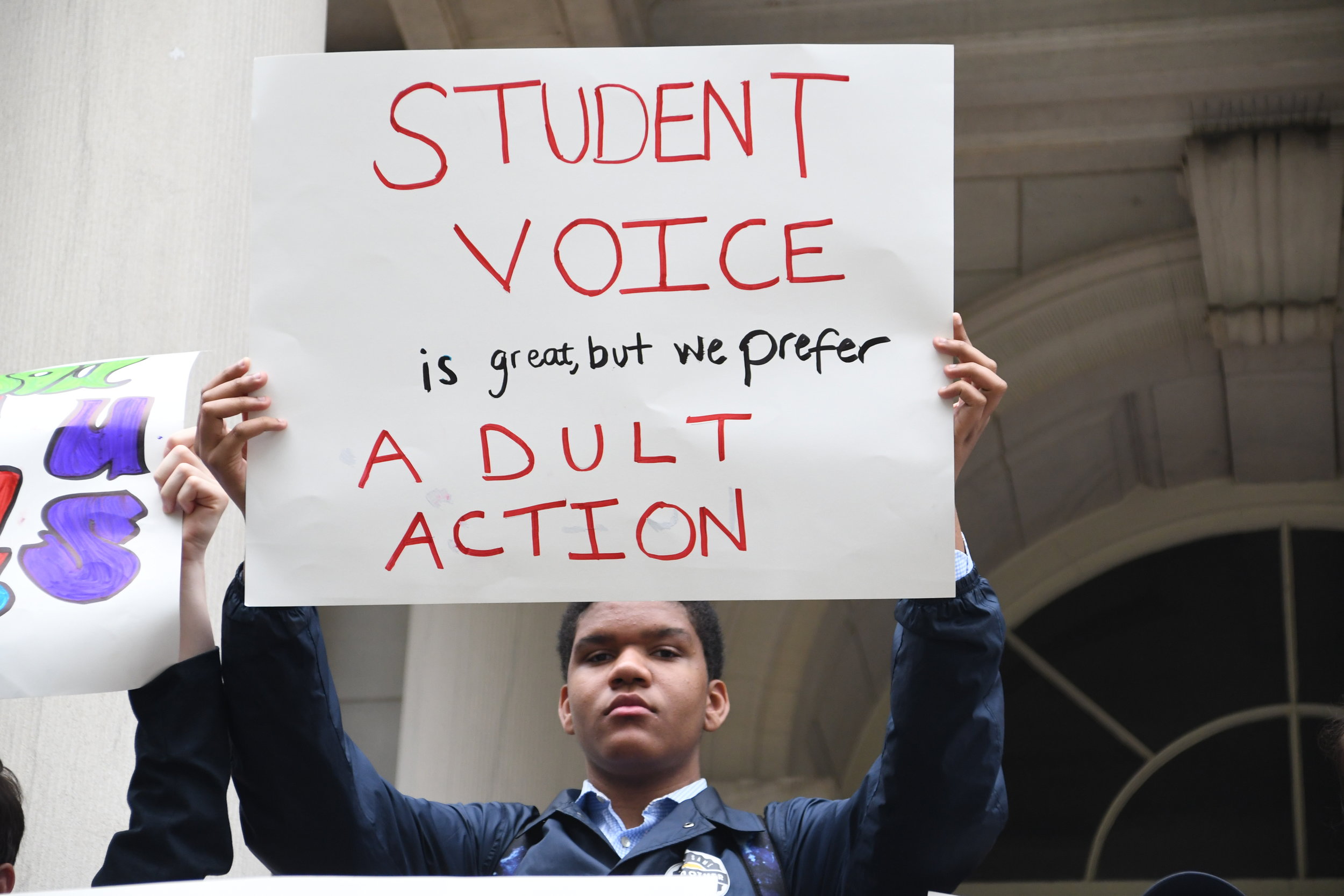

Brandon St. Luce, the author (photo: Dulce Michelle)

Sunday, May 17 of this year, marked 66 years since the Supreme Court ruled in Brown v. Board of Education that “separate is inherently unequal.” Yet today, many of our nation’s public school systems remain both separate and unequal. Nowhere is this clearer than in New York City, where I attend high school.

For five years, Mayor Bill de Blasio has touted an “Equity and Excellence” agenda while maintaining discriminatory admissions requirements at hundreds of middle and high schools that exacerbate segregation and inequity.

While these admissions requirements, known as “screens,” are not new, the ongoing COVID-19 pandemic has confirmed their unfairness, with nearly a third of public school students not having access to a laptop or reliable internet access, both essential during remote learning and for any student who wants to do the out of school preparation necessary for getting into the most competitive screened programs in the city. It has also given us a chance to hit the reset button. Many of the metrics that selective schools have traditionally used to sort applicants will not exist for the cohort of students applying to middle and high schools in December.

Screens vary from school to school, but screened schools have a long menu of options to choose from. They can restrict admission based on a host of factors, including, but not limited to: grades, attendance, punctuality, state test scores, zip codes, portfolio assessments, interviews, auditions, and school-administered specialty exams.

No, I’m not just referring to the city’s eight specialized high schools, for which the state legislature controls admission to the largest three. I’m talking about hundreds of screened schools squarely under the jurisdiction of Mayor de Blasio and the New York City Department of Education.

Admissions screens, which use flawed measures of “merit” to sort students, wind up segregating us by race and class. System-wide, two-thirds of students are Black or Latino and about 75% are poor. But at 30 of the most intensely screened public high schools, only one-third of students are Black or Latino and just 40% are poor. The effect is undeniable.

For more than two years, my peers and I at Teens Take Charge have been calling for integration through the removal of these admissions screens. We have proposed alternative policies in meetings with city DOE leaders, including Chancellor Richard Carranza and his cabinet of deputies.

Throughout the last two years, we have run two campaigns, both centered around the idea of abolishing admissions screens. Starting with the Enrollment Equity Plan, we proposed creating thresholds in all schools to make sure that at least 25% and no more than 75% of each high school's incoming freshman class has passed middle school state tests. This year we began to advocate for an “educational option” (ed-opt) model of admitting students in every school. This is not a new model, and it has been proven to help schools accept a diverse pool of applicants, including in my school, Edward R. Murrow High School, which is the most diverse school in the city. We have research that shows how much this would help with the demographic disparities in schools, backed up by the DOE’s own data.

We have led rallies, sit-ins, and, most recently, weekly “strikes for integration” at school campuses across the city. These strikes got major news coverage and turned out nearly 2,000 students from more than a dozen schools, including Beacon, NYC Lab School, and Millennium Brooklyn, three of the most heavily screened high schools in the city.

Every city and school official we have spoken to has acknowledged that screens contribute to segregation in our schools. They thank us for our advocacy. They tell us they are working on a solution. But nothing changes. The only high-ranking official who has not met with us or responded to our proposals directly is Mayor de Blasio, who we believe has been the primary obstacle to removing screens.

He didn’t even respond to his own School Diversity Advisory Group’s recommendations last year to end all middle school screens, some high school screens, and the ridiculous Gifted-and-Talented exam for four-year-olds. In September, he claimed that he would spend this school year doing public engagement on the recommendations, but there has yet to be a single public engagement opportunity.

This school year has come to an end, with the latter part being spent online with varying degrees of success, and it is irrational and illogical why screens should exist for students applying to schools next year. The only reasonable solution for next year is to forgo screens altogether and allow student choice to be the number one factor that guides where students are matched.

When demand for a school is greater than the number of seats, applicants could be matched using an equitable method called educational option (“ed-opt”) that is already in use at hundreds of city high schools. This system admits a proportional number of students who are below, at, and above grade level, producing academic diversity — which often translates to racial and socioeconomic diversity as well.

Proponents of screens and competition, namely, the Parent Leaders for Accelerated Curriculum and Education (PLACE), argue that screens are fair, bias-free assessments of hard work. As a student who recently took the Advanced Placement exam for U.S. History, I see a correlation in the way PLACE leaders talk about admissions screens and the way white folks in the Jim Crow South talked about literacy tests and poll taxes.

Low-income students and other vulnerable student populations are inherently punished by screens. Up until the pandemic, hundreds of thousands of New York City students did not have laptops or home WiFi, yet the high school admissions process has shifted entirely online and many screened schools require students to submit information or assignments online.

Then there are students like Jude, a 13-year-old at “one of the most competitive middle schools in the city” who recently started a petition to preserve the use of screens. Featured in a New York Post article, he is described as a “longtime Kweller Prep student.” Kweller Prep is a private tutoring company that charges thousands of dollars for its services, which include helping middle schoolers get into screened and specialized high schools. I’m sure Jude is a hard worker, but so are the thousands of other students across the city who cannot afford private tutoring.

To be sure, students like Jude and the parent leaders of PLACE are not our opponents. They are simply playing by the rules that Mayor de Blasio sets. And for far too long, those rules have allowed privileged students to cluster in a relatively small number of schools, bringing their social capital, PTA donations, and political savvy with them.

At a recent briefing, Chancellor Carranza gave us reason for optimism when he stated, in response to a question about next year’s admissions, that he and the mayor “will not penalize students in any way, shape, or form because of circumstances out of their control.” That’s exactly what screens do: penalize students for things outside of their control.

On April 16 of this year, Caranza also stated he would not allow “anyone to say ‘when we go back to the normal,' because the normal was never good enough for our kids. The normal meant some were privileged some were not.” The problems with screens have been identified by those who can create monumental change, yet their policies continue to benefit the most privileged in the city.

In the wake of this pandemic, Mayor de Blasio, Chancellor Carranza, and the Department of Education have an opportunity to shed New York City’s distinction as one of the nation’s most segregated school systems. This is the moment to start building the fair, integrated school system that was promised to us 66 years ago -- a system that gives every student the opportunity to thrive.

***

Brandon St. Luce is a junior at Edward R. Murrow High School in Brooklyn and co-leader of the policy team at Teens Take Charge, a student-led organization that advocates for educational equity in New York City schools. On Twitter @TeensTakeCharge.

***

Have an op-ed idea or submission for Gotham Gazette? Email This email address is being protected from spambots. You need JavaScript enabled to view it.