New Yorkers Run for President: History and Insights for 2016

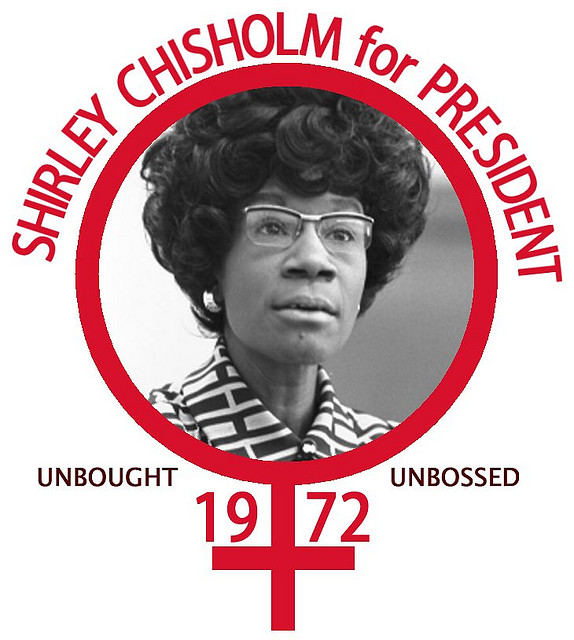

Shirley Chisolm for President, 1972

continued from page 1 - this is page 2 of 3

1932: New York's great depression fighter

Al Smith even lost his home state of New York in 1928, but his friend and colleague, Democrat Franklin D. Roosevelt, a former state senator, assistant secretary of the Navy, vice presidential candidate (in 1920), and distant cousin of Theodore Roosevelt, was elected governor. FDR proved an exceptionally capable governor, creating the nation's first state office to combat the Depression which settled onto the country after the stock market plunged in October 1929.

Hoover took limited steps at the federal level, including a program to make loans to sagging companies, but his measures were totally inadequate. Joblessness and despair rose. Hoover seemed indifferent. "Nobody is actually starving," the president told journalists. "The hobos, for example, are better fed than they have ever been." Homeless people lived in cardboard and tarpaper shacks dubbed "Hoovervilles." Hoover was re-nominated by his party but had no chance of winning.

Al Smith sought the Democratic nomination, arguing that Hoover's disastrous policies vindicated his progressive vision back in 1928. But Democrats turned to Roosevelt, an optimistic and capable leader who inspired confidence. FDR flew to Chicago to accept the nomination in person, something no other candidate had ever done. "I pledge to you...a New Deal for the American people" he told the convention.

The slogan "New Deal" stuck. FDR called for novel government methods to meet the unprecedented crisis but he was un-specific and some of his pledges, e.g., reducing federal spending, seemed outright conservative (and proved impossible to carry out). But his call for government action struck a chord among Americans weary of the Depression and Washington's seeming indifference. "The country needs and, unless I mistake its temper, the country demands bold, persistent experimentation," FDR said. "It is common sense to take a method and try it. If it fails, admit it frankly and try another. But above all, try something." Voters liked that can-do spirit. FDR carried all but six states.

1936: The New Deal endorsed

Roosevelt pushed through a dramatic array of "New Deal" reform measures in his first four years as president, including the National Recovery Act to help revive business; the Agricultural Adjustment Act to stimulate agricultural production; the Public Works Act to provide federal support for public highway and other public works projects; the Civilian Conservation Corps to provide jobs in reforesting; and other initiatives. As the economy slowly began to revive, he enacted still more reforms, including the Social Security Act in 1935. He proved to be a masterful leader who built confidence and support, even among potential opponents. When he needed a break from Washington, he travelled to his country home in Hyde Park, New York, which became almost an adjunct White House.

Easily re-nominated in 1936, FDR, a master campaigner, promised to extend and consolidate the New Deal. He denounced the Republicans as front men for "economic royalists," entrenched banking and business interests that had brought on the Depression and, given the chance, would root out the gains the New Deal had made for the American people. His administration had been struggling with "business and financial monopoly, speculation, reckless banking, class antagonism, sectionalism [and] war profiteering," he told an enthusiastic crowd at New York's Madison Square Garden near the end of the campaign. "Never before in all our history have these forces been so united against one candidate as they stand today. They are unanimous in their hate for me -- and I welcome that hatred."

Republicans had been challenged to find anyone willing to take Roosevelt on. They nominated Kansas Governor Alfred Landon, a lackluster, somewhat reluctant candidate. Landon actually agreed with much of the New Deal but dutifully attacked it for threatening American institutions, concentrating too much power in Washington, profligate spending, and excessive regulation. Sensing a need for a dramatic issue to energize his campaign, he called the Social Security law "unjust, unworkable, stupidly drafted, and wastefully financed," and a "glaring example of [New Deal] bungling and waste." He added that "It assumes that Americans are irresponsible [and] that old-age pensions are necessary because Americans lack the foresight to provide for their old age." Landon's appeal fell flat. FDR carried every state except Maine and Vermont.

1940: Sticking with proven leadership

By 1940, the depression was lifting and public attention turned toward the situation in Europe where war was raging and America's traditional allies, the British and French, were struggling against the onslaught of Nazi Germany. Aggression by Japanese imperial forces in the Far East was another rising concern. President Roosevelt searched for ways to assist the British in particular, but without violating U.S. laws which pledged the nation to neutrality. The Democrats, breaking with a tradition stretching back to George Washington of two-term limits for a president, nominated FDR for a third term. Roosevelt, like Wilson in 1916, stressed both preparedness and a commitment to peace. In one campaign speech, he assured parents that "your boys are not going to be sent into any foreign wars."

Republicans were discouraged -- people liked FDR's domestic policies, which seemed at last to be vanquishing the remnants of the Depression, and saw him as a strong leader needed at a time of international crisis. Party leaders, turning away from experienced politicians who could be tarred as obstructionists for their steadfast opposition to FDR's popular policies, sought a new, fresh candidate without Washington connections. They found him in Wendell Willkie, a public-utilities executive who had come to prominence as a leader in the fight against the Tennessee Valley Authority, a New Deal initiative for flood control and electricity generation in that region.

Willkie had switched from the Democratic to the Republican Party in 1939. He proved to be a magnetic, eloquent campaigner, critical of some New Deal measures but promising to keep most of it in tact if he were elected. He was mostly supportive of FDR's measured approach to international issues, breaking with Republican isolationists and conceding that the U.S. might have to intervene to stop aggression. But Democrats hammered at his lack of government experience, countering the Republican criticism of FDR seeking a third term with the chant "Better a Third Termer Than a Third Rater!" On Election Day, Willkie cut into FDR's 1932 and 1936 landslide majorities but lost by a sizeable margin. The next year, the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor brought the U.S. into World War II. Willkie supported the president's wartime strategies and occasionally served as an informal international envoy for the administration.

1944: New York's capable new governor vs. the champ

Republican Thomas E. Dewey, who had made his reputation as a district attorney prosecuting organized crime figures in the 1930s and early '40s, was elected Governor of New York in 1942. Two years later, he sought the presidency. Dewey campaigned on his executive record -- New York had a budget surplus and the governor was developing plans for postwar business and veterans' benefits.

President Roosevelt seemed tired. He had lost weight and looked haggard. There were rumors that his health was failing. The war effort had gone well -- the allies invaded France on June 6, 1944, just as Dewey's campaign was ramping up -- but the war had spawned over 150 bureaus, many duplicative, adding to the image of too much government in Washington. The Republican platform advocated streamlined, cheaper, and more efficient government after the war. Four more years of FDR's policies, the platform warned, "would centralize all power in the President, and would daily subject every citizen to regulation by his henchman; and this country would remain a Republic only in name."

Dewey, the capable, conservative executive, seemed tailor-made for the job. After twelve years in power, the New Deal had grown "old and tired and quarrelsome," the administration racked by "wrangling, bungling, and confusion." Dewey was vague on his plans for a post-war world but promised to shrink the federal government. Otherwise, "we may slip by gradual stages into complete government regulation of every aspect of our lives," he warned.

Dewey was careful and systematic but also stiff, unexciting, and not very personable. FDR rekindled the likeability and trust that Americans had valued for so long. In a September speech, he went after a Republican accusation that the Navy had been ordered to rescue the president's dog, Fala, from the Aleutian Islands after a presidential trip there. "These Republican leaders have not been content with attacks on me, or my wife, or on my sons," the president said at a campaign rally. "No, not content with that, they now include my little dog, Fala. Well, of course, I don't resent attacks, and my family doesn't resent attacks, but Fala does resent them."

Democrats piled on: Dewey lacked international experience and knew how to attack and tear down but had little constructive vision for the future. Dewey's final speech -- "let us resolve to put aside these years of cynicism and conflict...to throw off the nightmare of past years and breathe once more the atmosphere of peace and good will" -- did little to inspire confidence. FDR was the only president many Americans had ever known. He had led the nation through the Depression and now seemed close to leading it to victory in war. FDR won overwhelmingly, with 391 to 140 electoral votes.

1948: New York's accomplished but overconfident governor

Apprehension about FDR's health in 1944 were providential. In April 1945, the president died and was succeeded by Vice President Harry Truman, who had been a Senator from Missouri. Truman was ill prepared for the presidency. FDR had not told him about the secret project to develop an atomic bomb, which Truman, once he understood its awesome destructive power, decided to use against the Japanese to end the war in August 1945.

The Truman administration was beset by allegations of mismanagement. It was struggling to deal with the onset of the Cold War and the menace of communism, particularly in eastern Europe. Truman was nominated for a full term as president but his Democratic party was less than optimistic. Liberals thought him too conservative and established their own Progressive Party (the same name but no relation to TR's 1912 group) and nominated Henry A. Wallace, FDR's vice president from 1940 to 1944, to run for president. Many southern Democrats disliked Truman's civil rights positions and formed the States' Rights Democratic Party, dubbed the "Dixiecrats," and nominated South Carolina Governor Strom Thurmond for president. Truman's prospects looked dim.

Dewey, re-elected governor in 1946, by contrast, looked stronger than ever. He had maintained New York's budget surplus, signed the nation's first state civil rights bill, initiated the New York State Thruway, established the State Commerce Department to stimulate the post-war economy, and launched the State University of New York. The Republicans decided he deserved another shot at the presidency. As a campaigner, though, he proved to be overconfident (he called his campaign train the Victory Special) and vague, admitting he had "no easy answers" and warning that "the road to a happy future is likely to be pretty rocky."

But Truman, defiant and feisty, launched a vigorous campaign. He went constantly on the attack, warned that the country must not go backwards and that Dewey's election would usher in a return to the vicious cycle of boom and bust. Republicans would undermine labor unions and strengthen entrenched monopolies that threatened free government. The president assailed the "silent and cunning" Republicans who controlled Congress and had "a dangerous lust for power and privilege," and tied Dewey to "this Republican gang" who would "give tax relief to the rich at the expense of the poor" and do "a real hatchet job" on the advances brought under the New Deal.

On the other hand, for their inaction on initiatives he favored, the president was able to denounce the "do-nothing Congress" controlled by Dewey's party. Truman characterized Wallace and Thurmond as extremists on the left and right, respectively, warning that voting for them would just help the Republicans. Dewey continued his dignified campaign, confident of success. Truman won increasing support by being transparent, warmhearted, and genuine. The polls were close. In fact, the Chicago Tribune, buying into Governor Dewey's confident stance, carried a headline of "DEWEY DEFEATS TRUMAN" in its early editions the day after the election. But on Election Day, Truman had surged, winning by more than two million votes and an Electoral College margin of 303 to 189. Another New Yorker had gone down to defeat.

Even more New Yorkers have run for President, including the current crop of candidates - READ ON for page 3 of 3.

This is page 2 of 3. Return to page 1.

***

Dr. Bruce W. Dearstyne's latest book is The Spirit of New York: Defining Events in the Empire State's History, published in 2015 by SUNY Press.

***

Have an op-ed idea or submission for Gotham Gazette? Email This email address is being protected from spambots. You need JavaScript enabled to view it.

New Yorkers Run for President: History and Insights for 2016

Franklin D. Roosevelt (whitehouse.gov)

The 2016 presidential contest may very well pit two New Yorkers, Hillary Clinton and Donald Trump, against each other. In the 29 presidential elections from 1900 to 2012, New Yorkers headed major tickets nine times. Two (Theodore Roosevelt and Thomas Dewey) ran twice; one (Franklin D. Roosevelt), 4 times. New Yorkers faced each other twice (1904 and 1944), presaging the seemingly likely 2016 matchup.

New York's prominence in national politics is no surprise. Arguably the nation's most historically important state for many years, New York is something of a proving ground for the presidency. Succeeding as New York governor, for instance, demonstrates capacity to lead, address complex issues, manage politics successfully, and get things done. Simply serving as governor or U.S. senator from New York is almost always a guarantee of a high-profile. New York for many years had more electoral votes than any other state and even now has a sizeable number.

New York's significant role in presidential elections has a long and illustrative history.

1904: The judicious judge vs. the energetic president

Theodore Roosevelt (R), New York governor 1899-1901 and then vice president, became president in 1901 after the assassination of President William McKinley. Over the next three years, TR compiled a vigorous record, promoting conservation, taking legal action under the anti-trust law to dissolve a powerful railroad consortium called the Northern Securities Company, and supporting a revolution in Panama to achieve independence from Columbia and then negotiating an agreement to build a canal there to link the Atlantic and Pacific oceans. He was easily nominated by his party to seek a full term as president.

Alton P. Parker (D), chief judge of the New York Court of Appeals since 1898, was a proven Democratic vote getter in what was then a predominantly Republican state. His solid, well-reasoned opinions gave him an aura of authority and reliability, an advantage, his backers insisted, over the sometimes impetuous TR. Parker in January 1904 wrote the majority opinion in the case of People v. Lochner, validating a New York law regulating the working and safety conditions of bakery employees. It was an eloquent affirmation of the government's authority to regulate industry, and it helped him secure the Democratic party's presidential nomination in the summer.

Parker resigned as chief judge and, following the custom of the day, did not travel or make speeches beyond a few from the front porch of his estate, Rosemont, in Esopus, on the Hudson River near Kingston. He campaigned on frugality and economy in government, cautioned against foreign adventuring, and accused TR of secretly soliciting campaign contributions from railroad and banking magnates. TR denied the accusation and pointed to his energetic, proactive record as President. Parker generated little enthusiasm. A cartoon in the fall showed him in a rowboat near his dock at Rosemont, leisurely fishing and lamenting, "If I could only hook a real issue!" Americans in the early 20th century were ready for strong presidential leadership. TR won easily, garnering nearly 60% of the popular vote.

1912: the resurgent New Yorker

TR served as president until 1908 and was succeeded by his friend and Secretary of War, William H. Taft. TR had so much confidence in Taft that he easily convinced Republican leaders that Taft was his logical heir apparent. Roosevelt went off on a hunting trip to Africa and when he returned in June 1910, he quickly expressed displeasure at the way his successor had handled things. Taft, amiable and accommodating, had signed a tariff bill that increased rates on imported goods, weakened TR's conservation policies, and given in to Republican conservatives in Congress on other issues.

TR began attacking Taft and articulating a new political philosophy which he called "the New Nationalism." Roosevelt condemned court decisions that nullified state regulatory statutes and declared that "property shall be the servant, not the master, of the commonwealth...The...essence of any struggle for healthy liberty has been, and must always be, to take from one man or class of men the right to enjoy power, or wealth, or position, or immunity, which has not been earned by service to his or their fellows." Roosevelt sought the 1912 Republican nomination and won most of the primaries in the handful of states that had them that year. But Taft supporters denounced TR as a dangerous power-hungry radical who if elected might wield unprecedented executive power. They vowed to stop him at all costs. Taft forces controlled many state delegations and the president was renominated.

TR and his supporters cried foul, left the Republican convention, and then formed a new party, the Progressive Party, dubbed the "Bull Moose" party after TR declared he felt as "fit as a bull moose." The Progressive platform included workmen's compensation, old-age insurance, woman suffrage, and federal regulation of business, built around the slogan "Let the People Rule!" TR campaigned energetically, narrowly escaping assassination when a deranged man fired at him in Chicago. The Democrats nominated Woodrow Wilson, who had served as a progressive New Jersey governor and before that was president of Princeton University. Wilson campaigned on a platform of "the New Freedom," including strong federal regulation of business. Taft waged a weak, dispirited campaign. With the Republicans effectively split between Roosevelt and Taft, Wilson triumphed easily, Roosevelt came in second, and the hapless Taft carried only two states, Utah and Vermont.

1916: the progressive New York governor and judge

Woodrow Wilson pushed several progressive reforms through Congress, including the Federal Trade Commission, the Federal Reserve Act, a strong anti-trust law,, and a lower tariff. But after World War I began in 1914, public attention shifted to the balance between defending American trading rights on the high seas and at the same time avoiding being drawn into the war. Easily re-nominated in 1916, Wilson espoused military preparedness but also pledged to keep the nation at peace, campaigning on the slogan "he kept us out of war."

Republicans, reunited after their 1912 split, nominated former New York Governor and Supreme Court Justice Charles Evans Hughes. TR and Taft both endorsed him. Hughes had been a strong, progressive governor and a moderate, capable judge who favored government regulation. But he was an uninspiring campaigner, his speeches limp, too often laden with platitudes. Hughes so straddled the issue of peace and war that the Democrats dubbed him Charles "Evasive" Hughes.

The result was close in a number of critical states. The election hinged on California. That state's Republican governor, Hiram Johnson, who had been TR's 1912 vice presidential running mate, was lukewarm on Hughes. One day during the campaign, Hughes and Johnson were in the same hotel in Long Beach for several hours, but, due to a scheduling snafu, did not meet with each other. Hughes later apologized but Johnson thought Hughes had snubbed him and gave him only nominal support. Wilson narrowly carried California and the election. (The next year, 1917, Germany began attacking American ships with its submarines, leading Wilson to ask Congress for a declaration of war. Hughes later went on to be Secretary of State and Chief Justice of the United States.)

1928: New York's "Happy Warrior"

America was prosperous and at peace in 1928, which many people attributed to the benign, pro-business policies of Republican Presidents Warren G. Harding (1921-1923) and Calvin Coolidge (1923-1929). When Coolidge announced he would not run in 1928, Republicans selected his Secretary of Commerce, Herbert Hoover, as their candidate. Hoover, an engineer, had won acclaim for leading relief work in Europe after World War I and promotion of business and prosperity as commerce secretary. He campaigned as heir apparent of the two previous Republican presidents and promised to continue America's sunny prosperity.

People were satisfied, even complacent. It seems unlikely any Democrat could have defeated Hoover in 1928. Democrats selected a strong contender, Alfred E. Smith, governor of New York 1919-1921 and 1923-1928. Smith, the "Happy Warrior," was one of New York's most effective governors, consolidating state government, enacting the modern state budget system, increasing aid to education, and taking other initiatives. But Smith was also a "wet" -- he opposed prohibition, the outlawing of alcoholic beverages, which had been in effect since 1919. He was also a Catholic at a time when anti-Catholic bigotry was strong. Opponents whispered that Smith would be under the control of the Vatican and might even bring the Pope himself to Washington to take charge of the government.

Smith espoused a vision of a federal government which would address the issues facing the nation "along sane, sensible progressive lines." His informal campaign song, "The Sidewalks of New York," reminded audiences everywhere he spoke of his New York roots. That helped in some places but hurt the candidate in other areas which associated New York City with concentrated wealth, urban problems, and overly-liberal values, and associated Smith himself with the New York Tammany Hall Democratic organization. Smith did well in urban areas but he carried only seven states, all but one in the south, which had been strongly Democratic since the time of the Civil War.

READ ON - this is page 1 of 3 - New York Governor FDR runs for President and much more - Continue to page 2 of 3

***

Dr. Bruce W. Dearstyne's latest book is The Spirit of New York: Defining Events in the Empire State's History, published in 2015 by SUNY Press.

***

Have an op-ed idea or submission for Gotham Gazette? Email This email address is being protected from spambots. You need JavaScript enabled to view it.

The Next Step to Helping Immigrant Families Thrive

Council Member Menchaca, a co-author, promotes IDNYC (photo: @IDNYC)

In recent years, New York City has taken tremendous strides forward in supporting immigrants. Many of Mayor de Blasio's signature initiatives—particularly universal pre-kindergarten (UPK), IDNYC, and community schools—have offered vital new services to New Yorkers across the city that have been tremendously beneficial for immigrants seeking to fully integrate themselves into our society and see their families thrive.

Now, there's another critical step that New York City can take to build on these immigrant integration successes: investing in adult education.

New York City has the largest immigrant community of any city in the United States, with three million immigrants from all over the world—that's more than the entire population of Chicago. Immigrants help drive our city—accounting for 45 percent of the workforce and 49 percent of small business owners, and endowing the Big Apple with much of its incredible cultural vibrancy.

New York City has led the way in offering vital services to immigrant communities, in particular to children from immigrant households. But it's critical that we now move forward to ensure that immigrant parents are equally equipped to take advantage of new path-breaking city programs, and that means supporting adult literacy initiatives that help immigrant New Yorkers learn English and ensure basic reading and writing skills.

Adult literacy is crucial for helping parents know how to navigate the city and unlock the power of major policy achievements. To make UPK, IDNYC, and community schools live up to their potential, for example, we need to make sure parents are equipped with the tools they need to access them. English-speaking parents have a much easier time ensuring their children's educational success—for example, by being able to fully engage during parent-teacher meetings—and being able to proactively seek out the indispensable services provided at community schools.

Adult literacy is necessary for our immigrant communities, and more broadly, it's important for the economic well-being of our city. As a new report by the Center for Popular Democracy and Make the Road New York has found, directing additional resources toward adult literacy will raise immigrant New Yorkers' wages and increase tax revenues.

Take the example of Yanilda, a Dominican immigrant enrolled in English classes at Make the Road New York in Bushwick. Since beginning her classes, Yanilda notes, "I can help my niece with her homework. She's in kindergarten now and when I help her read her books, I learn too." Yanilda is also confident that her steadily improving English will help her get a better job. For her and thousands of others citywide who are lucky enough to have a spot in a free English class, adult literacy programs offer a win-win.

There are 1.7 million and 2.3 million Limited-English proficient residents like Yanilda, in New York City and New York State, respectively, according to the Census, and many others in need of basic literacy courses. Within immigrant communities there is a tremendous unmet need for English classes and adult basic education, with state funding now only sufficient to accommodate one of every 39 New Yorkers who need ESOL (English Speakers of Other Languages) classes. Simply put, adult literacy funding has not kept pace with the need.

That's why we need New York City to dedicate $16 million in its upcoming budget to new investments to help 13,300 students access adult literacy programs, including ESOL, Basic Education in Native Language (BENL), Adult Basic Education (ABE), and High School Equivalency Preparation (HSE).

We've made so much progress in expanding services to immigrant New Yorkers since Mayor de Blasio took office. It's time for New York City to take the next step in full immigrant integration by investing in adult literacy.

***

Carlos Menchaca is a member of the New York City Council. Theo Oshiro is the Deputy Director Make the Road New York. On Twitter: @cmenchaca & @maketheroadny.

***

Have an op-ed idea or submission for Gotham Gazette? Email This email address is being protected from spambots. You need JavaScript enabled to view it.