New York's Coming ConCon Battle

(photo via The Governor's Office on flickr)

New York's Constitution mandates that every 20 years New Yorkers be granted the opportunity to vote on whether to call a state constitutional convention. This referendum is next on the ballot on Nov. 7, 2017.

The unique democratic function of this referendum is to provide New Yorkers with a mechanism to bypass the Legislature's gatekeeping power over constitutional reform, which is a problem when the Legislature has an institutional conflict of interest with the people. Such a conflict occurs when the Legislature controls the constitutional powers of competing branches of government (e.g., the judicial and executive branches of government) and its own internal powers (e.g., legislative ethics, term limits, campaign finance, ballot access, and redistricting).

Since 1776, what is now the United States has had 236 state constitutional conventions and New York nine.

Fourteen states, including New York, have the periodic convention referendum. The last one to pass in the U.S. was in 1984.

My research finds two stages to the recent pro and con lobbying campaigns over convention referendums. The first stage is dominated by "yes" advocates; the second, which only occurs if the referendum polls well, is dominated by "no" advocates.

So far, New York is following this pattern, as it did in 1997, the last time the referendum was on the ballot. Since January 2015, 16 newspaper op-eds have called for a convention, while none has opposed. Governor Cuomo has announced support for a convention, including setting up a $1 million preparatory commission, while no prominent state politician has announced opposition.

Partially due to such one-sided public arguments, calling a convention is way ahead in the polls, leading 69% to 15% according to a Sienna Research Institute poll. Despite this lead, most political experts believe that the convention referendum will lose because waiting in the wings for a last minute PR blitz is a well-organized and deeply-financed opposition, which includes the special interest groups that excel at influencing the Legislature and fear the convention as a populist institution.

Opponents' campaign arguments directed to the general public will include: A convention will be outrageously costly, thoroughly corrupted by both the Legislature and special interests, wastefully redundant with the Legislature, likely to result in either too little or too much change, and controlled by majorities who will violate minority rights and minorities who will violate majority rights.

These arguments need to be subject to well-informed scrutiny. This can only be accomplished if media, think tank, and other public opinion leaders bring the opposition out of the shadows. Two-sided public debates, including dueling op-eds and interview programs, should begin now.

In a democracy, one reason public campaigns for vital elected offices, such as U.S. President, start many months before election time is that time is needed to have a well-informed debate. Open, sustained conflict also breeds popular interest. If opponents aren't willing to engage publicly, the public and press will remain uninformed, which allows last minute, sound-bite sized fearmongering to thrive.

Starting a two-sided public debate early also helps compensate for New York's loophole-ridden campaign finance referendum disclosure laws, which aren't a match for modern, anti-convention referendum politics, including the complex influence-laundering schemes that accompany them. For example, New York doesn't require disclosures during the last 19 days before a referendum—just when the attack ads become most intense.

No more fundamental right exists in a democratic system of government than the people's right to reform their government despite legislative opposition. New York's upcoming debate over how best to implement that right should be treated as seriously as the U.S. presidential election. The framers of New York's 1846 Constitution who bequeathed this right to us in the form of the periodic state constitutional convention referendum would have wanted no less.

Instead of a one-sided pro convention "debate" followed by a one-sided last-minute anti-convention "debate," we need a sustained multi-sided debate commensurate with its importance.

***

J.H. Snider, the president of iSolon.org, is the editor of The New York State Constitutional Convention Clearinghouse and author of Does the World Really Belong to the Living? The Decline of the Constitutional Convention in New York and Other US States, 1776–2015.

***

Have an op-ed idea or submission for Gotham Gazette? Email This email address is being protected from spambots. You need JavaScript enabled to view it.

School Diversity Benefits All Children - and Parents

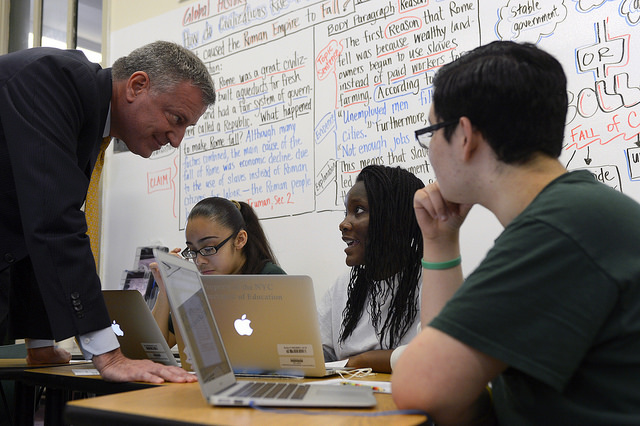

Mayor de Blasio on a school visit (photo: Rob Bennett, Mayor's Office)

My four-year-old daughter has a good friend at preschool who happens to have the same name. I'll call them both "Maya." My daughter is Asian, and her friend is Latino. Recently, a classmate said, "There are two Mayas in our class. One is white and the other is brown." My Asian daughter is the "white" Maya. The classmate's mom probed why he categorized the two Mayas this way, but didn't get much of an answer. Innocently, the boy didn't realize why his categorization was inaccurate or unusual.

In preschool, children are just beginning to make sense of things, applying lessons and parallels - sometimes accurately and sometimes not - from the world around them.

My daughter attends University Settlement Park Slope North/Helen Owen Carey Child Development Center ("Helen Owen Carey"), which manages to maintain a rare balance of racial and income diversity. I really appreciate this aspect of our preschool. Exposure to classmates from a wide range of racial and economic backgrounds is important. Young children need precisely this type of exposure, even if the process by which they come to understand it can be messy. Incidents like the above are awkward, but it's good that my daughter and her classmates are at a school where children can start to take stock of our diverse community. I am glad that Maya's classroom more closely mirrors the population of Brooklyn as a whole, and not just that of our Park Slope neighborhood.

Maya and her classmates have unique learning opportunities as a result of their school's student body, both formally and informally. In a lesson themed "All About Me," Maya and her classmates examined their physical appearance including differences in skin tone which they later put on a color spectrum, indirectly allowing the children to consider race.

Parents and families can also play an important role in this learning. Each spring, my husband and I go into our children's preschool classrooms to teach mini-lessons about two holidays related to our ethnic heritage, Chinese New Year and Burmese New Year. Even casual exposure can expand young children's sense of the world. My three children have sampled Haitian food at preschool potlucks, learned about latkes and matzo, and shared homemade mochi at their own birthday parties.

We need more public school classrooms that look like my daughter's preschool class.

The New York City Department of Education's recent decision to allow principals at seven public schools to set aside a percentage of seats for particular categories of students (such as low-income students, English Language Learners, or those involved with the child welfare system) in the interest of school integration is a promising and needed measure.

Once a more diverse study body walks through the classroom doors, however, a new and more intensive challenge begins – that of educating students of widely varying backgrounds and building a community from these children and their parents. And while it may be simpler to work with kids with roughly the same background and starting point, we know the value of a more diverse learning environment for everyone involved.

Parents in a racially and economically diverse school do face unique challenges when negotiating relationships and building community at those schools. For the most part, parents – including myself - at our preschool socialize more with others like themselves – racially, economically, or otherwise. This unfortunate segregation occurs politely and all too naturally, despite good intentions, and persists although many Park Slope parents chose the school precisely because of its diversity.

However, I have observed how we all grow more comfortable with one another over time and shared experiences. We nod "hello" when we run into each at drop-off or pickup, racing to avoid the dreaded late drop-off or pickup that occasions a visit to the administrative office. Parents share tips about the kindergarten application process, often in groups wider than our social circles. And so on.

Community building is tough, especially within diverse communities, even when this very diversity is what drew you into that community in the first place. I am thankful for the chance to participate in Helen Owen Carey's community. Maya's older brother now attends PS 321, a popular and sought after public elementary school in Park Slope. I've been satisfied with the caliber of instruction he's received there and appreciate the school's deeply engaged parent community. Unfortunately, it lacks the diversity I so love about our preschool. My children have been exposed to a level of diversity before entering kindergarten that they may not experience again in New York City public schools – maybe in their educational careers. That alone is priceless.

I benefit from the fact that my son's elementary school is a one mere block from my apartment, and the fact that playdates with my son's classmates are easy to arrange because everyone lives within five minutes. I have enjoyed getting to know many of his friend's parents, with whom I have a lot in common. That said, there is value in exposure to – and perhaps even building a more tenuous relationship with – parents with whom one does not have a lot in common and most likely will never become close friends with. Learning about other parents' experiences and the challenges they may face has expanded both my sense of the privilege I enjoy, as well as my broader understanding of educational equity.

As for my three children, as much as I appreciate the fact that we are zoned for PS 321 and what that means for their educational foundation, I hope they will not only reap benefits from their time in preschool but have more opportunities for rich, demanding, and diverse educational experiences in public school and beyond.

A good preschool friend of my son lived far away in another part of Brooklyn and is from a working class background. I didn't get to know his parents beyond the usual salutations and pleasantries, and we have not kept in touch. But I hope my son will remember his old friend should he meet other kids who remind him of the friend and that this will help my son keep an open mind and heart to others from different racial and income backgrounds. This hope might be impossibly idealistic, but it is ultimately what we need to achieve from school integration.

***

Khin Mai Aung has three children aged two, four, and six who attend preschool and public school in New York City. Previously, she was Director of the Educational Equity Program at the Asian American Legal Defense and Education Fund, and she currently conducts civil rights enforcement for the state of New York. The views contained in this article are solely her own.

***

Have an op-ed idea or submission for Gotham Gazette? Email This email address is being protected from spambots. You need JavaScript enabled to view it.

State Senate GOP Plays Politics with Anti-Semitism at CUNY

CUNY School of Law

New York State Senate Republicans are using the existence of anti-Semitism on CUNY campuses as their latest excuse in a ruse to gut the city university system's budget by $485 million, and shifting the financial burden of the cuts to CUNY students and their families.

Last week, Senate Republicans including Senator Kenneth LaValle, who chairs the Senate Committee on Higher Education, vowed to slash CUNY funding in order to "send a message" about anti-Semitism and intolerance on CUNY campuses. This message that Republican senators are sending is clear: Senate Republicans are using Jewish students on CUNY campuses as pawns in a budget battle that belittles incidents of anti-Semitism and excuses draconian budget cuts that would jeopardize the financial health of my classmates.

Intolerance and discrimination are real, and are endemic in our society. Our elected leaders should make a conscious effort to make all public institutions, including CUNY, as free from discrimination and intolerance as possible. As a Jewish CUNY student, I have witnessed my fair share of anti-Semitism (and other discrimination) within the CUNY system. Cutting funding is the last thing to do in response, though.

I cringe when I hear my fellow students decry the "Zionist administration" at CUNY or when thinly-veiled prejudicial comments are used freely on my campus and others against various groups. I welcome, encourage, and applaud efforts on a city and state level to address bigotry and prejudice on CUNY campuses. But the Republican effort to tie funding dollars to incidents of anti-Semitism will only further alienate students who feel victimized by intolerance.

Making matters worse, this politically motivated move endangers the prospects of 500,000 CUNY students and countless future students in our city who will consider enrolling at a CUNY school because of the affordability and quality of education that the system offers.

As the threat of unprecedented budget cuts lingers, CUNY students are growing anxious that we will not have the opportunity to continue our tradition of service. Over the past few weeks, my classmates and I have protested the potential cuts - we are fearful that our tuition will increase exponentially while our opportunities decrease. Lawmakers in Albany cannot allow these cuts to go through, resulting in the loss of precious programs and the dismissal of invaluable faculty members.

While the governor's office says that CUNY is fully funded in the executive budget, we want to make sure that the budget deal reached before the end of this month does indeed leave CUNY heading in the right direction, not backward. We certainly cannot allow Senate Republicans to push for cuts under the guise of punishing disturbing episodes of anti-Semitism. We must fight these episodes with more education, not less.

The State's historic commitment to funding the CUNY system has ensured that our quality education remains affordable, and that students of all backgrounds and financial circumstances have access to this education. An affordable CUNY system is a system that leads to students giving back to our city and state.

For example, the CUNY School of Law student body is largely focused on public-interest law. From defending indigent clients in criminal court to advocating for legislation that makes public benefits accessible to all New Yorkers, CUNY Law students are investing back into the people of our city and state.

Now, more than ever, we need our state government, including and especially the Senate GOP, to have our backs. Addressing anti-Semitism and discrimination on CUNY campuses is a legitimate concern that should be confronted. But conflating incidents of anti-Semitism and prejudice with the need to fully fund CUNY schools is a disservice to the people of this city and state.

The path forward is clear: fully fund CUNY and also make every effort necessary to tackle discrimination on CUNY campuses.

***

Jeremy Rosenberg is a student at CUNY Law School and president of the CUNY School of Law Democrats. He is on Twitter @JeremyR1992.

***

Have an op-ed idea or submission for Gotham Gazette? Email This email address is being protected from spambots. You need JavaScript enabled to view it.