Safe and Healthy Housing for All New Yorkers

(photo: Ed Reed/Mayoral Photography Office)

I just can't take the mice and the mold anymore.

For years, I have lived in a Staten Island apartment in desperate need of repair. I live there with my daughter, and we've constantly struggled to get our landlord to fix the problems that make our home an unhealthy place to live.

Over the past six years, we've frequently gone without heat and hot water, faced endless mold growing in our cabinets, and suffered rodent infestations that simply won't go away.

We've asked the landlord time and time again to make the repairs to the apartment that we need, but, when he finally does something, he only applies quick fixes. For instance, after we pushed hard for him to replace our moldy cabinets, he finally gave in—but the leak that caused the mold is still there, and it will soon grow again.

Ours is the story of thousands of New York families who suffer dangerous and unhealthy living conditions because of landlords who put profit above people. In my case, the conditions caused by the landlord's failure to make the necessary repairs have made my asthma worse; last week, I had to go to the hospital because of a respiratory infection. And, like any mother, I worry constantly about how our unhealthy apartment is affecting my daughter.

This type of problem afflicts tenants across the city. That's why it's so important that the New York City Council pass an important bill this year, Intro. 543, that addresses the underlying conditions that bad landlords like mine so often fail to address.

Here's what Intro. 543, introduced by lead sponsor Council Member Ritchie Torres, does: in the case that a landlord refuses to address the underlying condition causing a housing violation (for instance, a leak that produces mold), the bill would empower tenants like me to take our claims to housing court.

This is important because, all too often, when landlords finally act to address housing violations, they fail to deal with the physical defect or failure in the building system that causes the violation. An example with which many New Yorkers will be familiar: the landlord who patches the dripping ceiling or paints over mold, but fails to fix the leaky pipe that's producing the problem.

Currently, the city's housing agency (HPD) is only able to investigate up to 50 cases per year related to underlying conditions. The department does not currently have the capacity to fully take on all the cases that exist, which is why tenants like me need the legal recourses provided by this bill.

It's time for landlords to accept responsibility for ensuring that tenants like my family are living in apartments that are safe and healthy.

But landlords who profit enormously off of unhealthy apartments won't act alone. We have to make them, and that takes a change in the law. We need the City Council to pass Intro. 543 as soon as possible. If they don't, too many New Yorkers like me won't have the tools to ensure that our landlords make the repairs we need to make the mice and the mold go away.

***

Dulce María Rivera is a member of Make the Road New York, the largest grassroots community organization in New York offering services and organizing the immigrant community. On Twitter: @maketheroadny.

***

Have an op-ed idea or submission for Gotham Gazette? Email This email address is being protected from spambots. You need JavaScript enabled to view it.

Looks Matter, Especially in Public Housing

Hammel Houses vs. New Affordable Housing; David Schalliol, Affordable Housing in New York

As time marches on, and NYCHA projects stay the same, the sense of public housing as an isolated, stigmatized part of the city has grown. When most NYCHA projects were created between the 1930s and 1960s, boxy red brick apartment houses were pretty typical for a wide range of the city's residents. Since the 1960s, however, the city's affordable and market housing developers and architects have better integrated their towers into existing neighborhoods and experimented with exterior treatments including stone veneers, glazed brick, multi-colored bricks, glass, tiles, metal accents, and much more. Today's affordable housing buildings, in neighborhoods like Melrose in the Bronx, are often as attractive, and often more carefully designed, than unsubsidized apartment buildings.

NYCHA, by contrast, has preserved and renovated its red brick towers, mostly because to do anything else has been prohibitively expensive. In addition, because most NYCHA towers are fifty years or older, NYCHA's capital division is forced to go through a lengthy and expensive historical review process for basic renovation projects even when there is no architectural distinction at all to the towers undergoing renovation. Residents seem equally reluctant to embrace any changes, despite the longstanding sense among many residents that their apartments may be a good deal, but building exteriors are unattractive and isolating.

If we have learned something over the decades it is that curb appeal matters, especially when it comes to affordable and public housing. If NYCHA is going to attract and retain working families in the long term, some updates are long overdue. How housing looks also plays a role in how much pride people feel in their surroundings and how they treat those environments. The institutional appearance of NYCHA arguably discourages pride of place among many residents and visitors alike.

Appearance also has an even more important "other directed" quality that influences the politics and funding of housing. How the city's population as a whole feels about NYCHA is crucial as federal sources of funding, which have provided nearly all of NYCHA's subsidies for eight decades, dry up. Few non-NYCHA residents are eager to foot the bill to preserve the basic brick public housing towers in their neighborhoods, some of which also have serious social and crime issues that detract from neighborhood safety. If NYCHA projects, however, fit in better or enlivened surrounding neighborhoods, city residents as a whole might be more eager to subsidize the system out of their local taxes.

In New York, nationally, and around the globe there are many efforts underway to alter the visuals of subsidized housing. Some of these strategies are worth considering or adapting for NYCHA. The creative approaches featured here share in a tradition of adapting existing towers without displacement of current residents. Many of these adaptations would be expensive, far beyond NYCHA's current budget capacity. The De Blasio administration, rather than NYCHA, could sponsor and pay for a few demonstration renovation projects of NYCHA projects out of the city's capital budget (or the "preservation" budget of the Housing NYC plan) that could point the way to a new look.

New "Skins" for Old Buildings

There are many good reasons to pursue a policy of "re-skinning" or recladding NYCHA buildings with panels of various materials. NYCHA's red brick towers are minimally attractive and expensive to repoint. New "skins" available today, overlaid on top the brick, could provide extra insulation and additional protection from elements. New mechanical systems could also be run beneath or through the new exterior panels thus improving water, heat, electrical, and even internet service to residents. In the Rockaways, for instance, private developers made good use of reskinning to rebrand and redevelop a decayed subsidized project that had been poorly managed by its former owners. This approach could be adapted for NYCHA buildings as well.

(L and M Recladding in the Rockaways)

NYCHA, as part of the planning for Sandy Recovery projects, asked some of its participating architects to include with their basic repair plans more ambitious visions. The results are impressive and indicate the adaptability of the current NYCHA inventory—if costs were not such a limiting factor. The images make clear that new surfaces covering these places could work better for residents (in terms of mechanical systems and insulation) as well as make developments more inviting parts of neighborhoods.

(Red Hook Houses Recladding Proposal, NYCHA Capital Projects Division + KPF, ARUP)

Finding "Lost" Details

Cosmetic changes, at more moderate costs, could deliver some powerful visual results that might be welcomed by both residents and neighbors alike. The Dearborn Homes on Chicago's South Side, for instance, have been renovated and given appealing Georgian details. These alterations would be particularly welcome in residential areas of Queens and the Bronx where NYCHA towers often form a strong contrast to surrounding homes and apartment buildings.

(Dearborn Houses in Chicago Before and After, HPZS Architects)

Rediscovering Retail

The best of the early housing projects—First Houses, Williamsburg Houses, and Harlem River Houses—included stores and community facilities open and connected to their surroundings. Federal rules, and other factors, led to the elimination of most stores on NYCHA grounds from the 1940s to the 1960s, when most projects were built. The absence of vibrant street life and commercial, and the security stores provide for pedestrians, has been a major criticism of NYCHA design.

Today's NYCHA leaders, for a mix of financial and social reasons, are considering the redesign of ground floor spaces with new stores that could add liveliness and much needed revenue. The example of Stuyvesant Town could serve NYCHA well, where new ground floor retail has helped perk up public spaces for a middle-income complex. More stores and street life on and around NYCHA might go a long way to creating safer public spaces as well.

(Stuyvesant Town New Café at Ground Level; David Schalliol, Affordable Housing in New York)

(Stuyvesant Town New Café at Ground Level; David Schalliol, Affordable Housing in New York)

Signage and Balconies

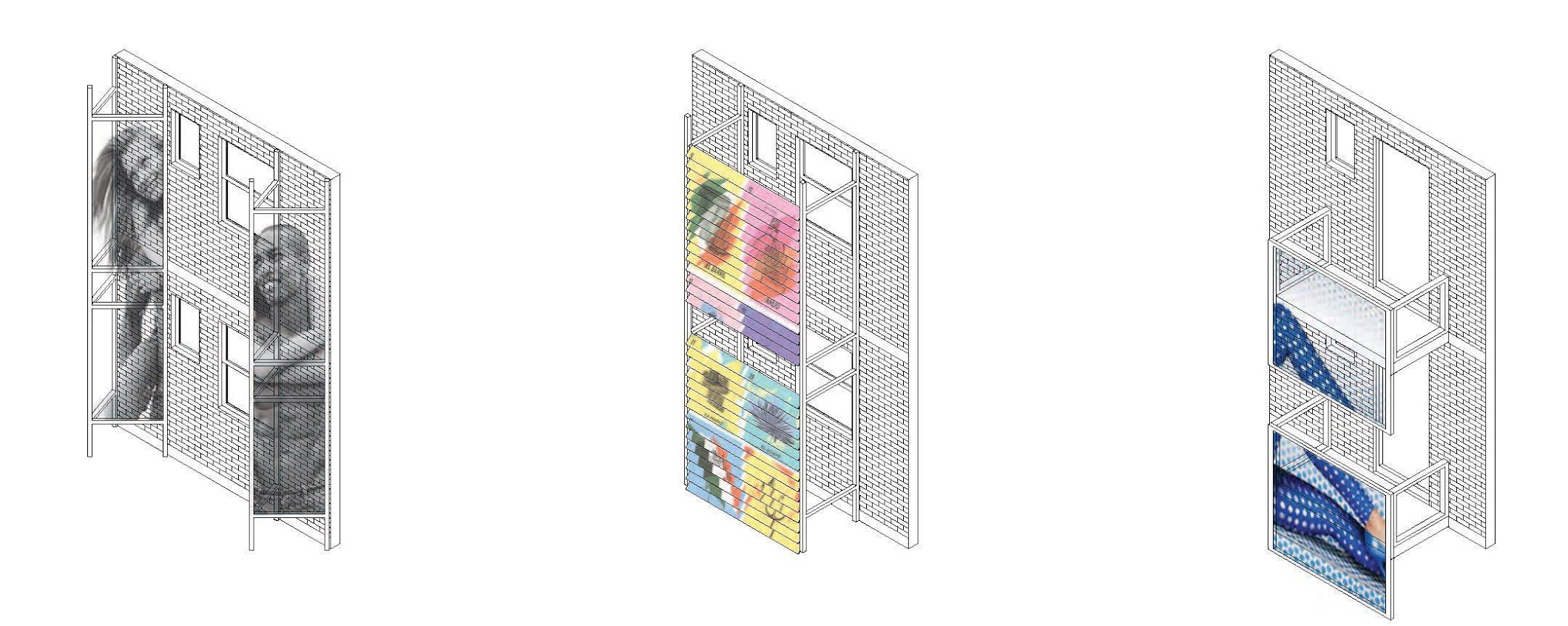

New exterior adaptations have the potential not only to brighten up drab exteriors but also contribute directly to NYCHA's financial bottom line. The creators of public housing in the 1930s disliked commercial signage in residential areas, but today's urban neighborhoods are often enlivened by signs of all types. Architect Matthias Altwicker proposes that new exterior signage, some with advertising, could enliven the building exteriors. Some might hang off existing walls, while other signs might be part of new balcony systems.

(Commercial Additions to Typical Red Brick Towers, Matthias Altwicker Architect)

(System of Simple Applied Structures to provide sun shading for all types of orientation, advertising surfaces, and adding balconies where floor plans permitted.)

Signage could also be applied to new structures rising on NYCHA grounds. FEMA is providing money for moving boilers and other mechanical systems above the flood zones. Most of the architects commissioned by NYCHA to create hurricane resistant buildings have simply matched the red brick boxes to their surroundings. Altwicker proposes, instead, that the new brick buildings instead become lighted beacons in their neighborhoods. These could provide a sense of orientation for the areas, brighten dark areas at night, and potentially feature community news and events along with space for advertisements to generate revenue.

(Elevated Mechanical Buildings as new "Lightboxes" by Matthias Altwicker Architect)

The examples of design strategies for NYCHA are provided here to get the city and NYCHA residents thinking about ways of refreshing dated housing projects; this quick set of examples is not designed to be an exclusive list of options. Around the globe and in New York, however, designers and housing authorities are giving new life to aging public housing projects. New York should join in this tradition of renewal to make a more livable city—for both NYCHA residents and those in surrounding neighborhoods.

*This is part three of a three-part series on NYCHA from Nicholas D. Bloom and partners*

Read part one: Rebuilding NYCHA: A Fresh Look

Read part two: Goodbye to 'First Generation' NYCHA

***

Nicholas Dagen Bloom and Matthias Altwicker are Co-Curators of the current exhibition at the Hunter College, East Harlem Gallery, Affordable Housing in New York.

***

Have an op-ed idea or submission for Gotham Gazette? Email This email address is being protected from spambots. You need JavaScript enabled to view it.

Goodbye to 'First Generation' NYCHA

photo: David Schalliol, from Affordable Housing in New York

Should NYCHA give up its controversial plan to generate revenue by adding mixed-income 50/50 percent (market/affordable) buildings at the Wyckoff Gardens and Holmes Towers public housing developments? Many residents and activists at these two sites dedicated for "infill" as part of NYCHA's NextGen Neighborhood initiative remain leery at the prospect of change, even if it means they won't get the renovated apartments and new community facilities that market-rate development can partially bankroll.

Establishing a precedent for some market-rate housing on NYCHA grounds at these developments, despite resistance, remains one promising avenue to improving both public housing apartments and NYCHA's bottom-line. The fees from market development won't pay for a new utopia, but they could make a major difference in long-term quality of life. New York has, after all, finally reached the end of the compromised housing model we should refer to as "First Generation" NYCHA. Dramatic changes are long overdue, and probably essential, if NYCHA is to remain desirable housing for the city's working class.

NYCHA has made its reputation on making the best of difficult situations rather than building utopia. The founders of the New York City Housing Authority in the 1930s, such as Mayor Fiorello LaGuardia and settlement house leader Mary Simkhovitch, wanted public housing to clear the millions of apartments in tenement slums. When money was no object during the New Deal they built America's greatest and most enduring public housing projects: Harlem River Houses and Williamsburg Houses. But when the press and federal government found out how much this high-quality housing cost, NYCHA was forced to economize on everything (such as no closet doors!) and it began to mass produce red brick, often bleak, "towers in the park" across the city's neighborhoods.

(l-r: Harlem River House (1930s), Rangel Houses (1950s); David Schalliol, Affordable Housing in New York)

Even more important compromises followed. The founders had aimed for mostly working class families whose rents covered expenses, and they carefully screened applicants to choose those who would make peaceable, rent-paying tenants. But as the years went on federal directives and public pressure forced the agency to accept poorer families. The number of families on public assistance, many with multiple social and family issues, skyrocketed by the 1970s. NYCHA family incomes, even those with jobs, began to lag well behind those of the rest of the city. Weak rental returns were papered over with federal subsidies, but social problems in many projects became severe.

Behind the scenes NYCHA leaders pushed back on federal rules as best they could, varying building heights, including community centers, adding more maintenance staff, constructing higher-income developments financed with city money (rather than federal), creating a housing police, building on vacant land, and prioritizing working families. But Robert Moses, whose top priority was slum clearance, and federal bureaucrats, who provided most of the funding (and still do today), called most of the shots. As a result, First Generation NYCHA (today's 178,000 units) became isolated physically and socially, with a more racially segregated population and fewer economic opportunities than the city as a whole. A quarter of NYCHA's tenants regularly fail to pay their (low) rents and crime is much higher on and around NYCHA projects than almost anywhere else in the city.

Billions in federal dollars have been spent to maintain these complexes, now aging en masse. But today they suffer from years of federal cutbacks that began around the year 2000, which have led to deferred maintenance and other reductions in service. Energy and labor costs are out of line with rent/subsidy sources. Still fully occupied and low rent, NYCHA projects are about the best outcome that could be expected from a set of nearly debilitating compromises.

(Polo Grounds Maintenance Crews; David Schalliol, Affordable Housing in New York)

Saving the system requires dramatic changes. While NYCHA's early leaders who built these places always intended to provide quality permanent homes, they would not endorse the notion that what they built should be preserved for another century without alterations or adaptations. They built what they could, where they could, as well as they could given limited funds. But they rarely built for the ages and their ideas evolved continuously based upon program, requirements, neighborhood opposition, and more.

Nor would NYCHA's founders endorse the notion that public housing or new buildings proposed in the NextGen plan should be reserved only for the poor, as is the aim of many current critics. To the contrary, they believed in a working-class system that was mostly self-supporting and self-policing. NYCHA's founders endorsed the notion of mixed-income public housing projects and would find the resistance of today's residents to income mixture unwise from both a social and financial perspective. NYCHA had a much better rent collection record, and projects were safer, when the system housed a wider income range of New Yorkers.

Today's residents and housing advocates are right to demand a voice in the process, and maybe even priorities for new apartments that rise on the grounds. But they also need to accept that financially and physically First Generation NYCHA is unsustainable without new sources of non-governmental revenue. No federal, state, or local official is promising to deliver the billions needed for additional renovation. Mayor de Blasio has committed only $300 million of the city's money to new roofs; federal operating and capital subsidies, which still provide the majority of NYCHA funding, have been in freefall since 2000; and Governor Cuomo's budget proposal provides $20 billion for new affordable housing and nothing for NYCHA.

Rethinking NYCHA design, moreover, is long overdue. The plain brick buildings are, by and large, poorly integrated with their surrounding neighborhoods. The vast open spaces surrounding most towers are often underutilized, unsafe, or unnecessary, such as parking lots in Manhattan. Many NYCHA residents recognize that their complexes could use more income diversity; more units, especially for seniors who could be moved out of larger family apartments; new community facilities; and more stores to create variety and safety, through additional eyes on the street. Yet the cash to pay for these upgrades, including renovation of their own apartments, is more likely to come from a mix of market-rate and affordable development rather than new subsidies alone.

First Generation NYCHA was a compromise solution that seems to have run its course. Housing advocates need to be honest with NYCHA residents about the realistic versus imaginary paths to a better system. Infill isn't the only option for rebuilding NYCHA, and NYCHA leaders are pursuing every source of funding they can find, but residents should take advantage of the fact that New York's overheated real estate market could help fund the renovation of their buildings. It is time for NYCHA residents to make peace with city leaders, and begin to welcome a mix of market dwellings with subsidized ones, so that another generation can benefit from public housing.

*This is part two of a three-part series on NYCHA from Nicholas D. Bloom and partners*

Read part one: Rebuilding NYCHA: A Fresh Look

Read part three: Looks Matter, Especially in Public Housing

***

Nicholas Dagen Bloom and Matthew Gordon Lasner are Co-Curators of the current exhibition at the Hunter College, East Harlem Gallery, Affordable Housing in New York and Co-Editors of the anthology by the same name available here.

***

Have an op-ed idea or submission for Gotham Gazette? Email This email address is being protected from spambots. You need JavaScript enabled to view it.