Cuomo’s Preparatory Commission Should Prioritize Fixing ConCon Process

photo: Kevin P. Coughlin/Office of Governor Andrew M. Cuomo

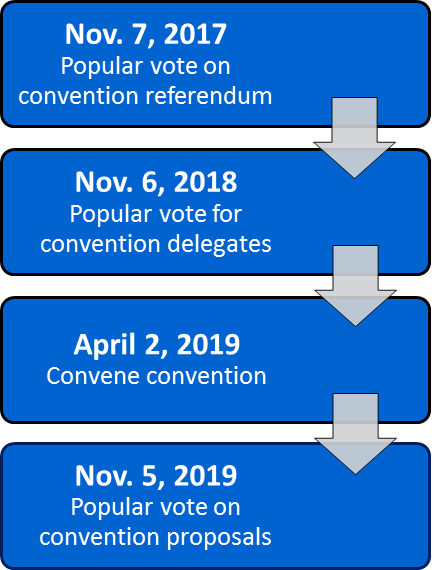

In his 2016 State of the State Address, Governor Andrew Cuomo promised to “invest $1 million to create an expert, non-partisan commission to develop a blueprint for a [constitutional] convention.” New Yorkers will vote on Nov. 7, 2017 on whether to call a state constitutional convention and the commission would educate the public on what a “yes” vote might entail.

Traditionally, such commissions have taken the constitutional convention process itself as a given and focused on the substantive changes to state government a convention might propose; for example, today’s hot-button issue of legislative ethics. But that agenda is too limited. The commission should also consider reforms to update the convention process.

In the past, a potent argument against calling for a convention has been that a convention would merely replicate the Legislature’s corruption. For example, some major New York good government groups opposed calling a convention in 1997, the last time the question was on the ballot, by arguing legislators elected as convention delegates would dominate a convention (approximately 5% of the delegates elected to New York’s last convention in 1967 were sitting legislators). Legislators elected as delegates would also unjustly receive two salaries: one for serving as a legislator; another for serving as a convention delegate.

Clearly, fixing such procedural problems is critical to winning popular support for a convention.

Governor Cuomo has taken a good first step in addressing such arguments by announcing that the commission will be “authorized to recommend fixes to the current convention delegate selection process, which experts agree is flawed.”

But that is not ambitious enough.

The Legislature currently controls too much of the constitutional convention process. In passing enabling legislation, it has every incentive to exacerbate rather than fix procedural problems so as to make a “yes” vote as unappealing as possible to the electorate. The Legislature has this incentive because New York’s Constitution includes a convention process designed to serve as an effective check on the Legislature’s power. That—and not because a convention would be no different than itself—is why the Legislature is an intractable enemy of conventions.

Other states have used the constitutional convention process to fix the constitutional convention process itself, and that should be a major goal of New York’s next convention. For example, concerns about legislators serving in a convention could be easily addressed if legislators were banned, as is done in Missouri and Michigan, from running as convention delegates.

Such a ban shouldn’t be controversial. Plural office holding is universally banned in American state constitutions because it violates the checks and balances principle. Elected officials, for example, cannot simultaneously serve in the legislative and executive branches. Some states ban public officials from simultaneously holding two public offices even when not violating the checks and balances principle. The more universal principle involved is that it is hard for officials simultaneously holding two separate public offices to fulfill their fiduciary duties of care and loyalty to the public.

But the plural office holding problem is merely one of many procedural issues that a constitutional convention could fix. Instead of New York’s past practice of making procedural concerns an objection to calling a convention, they should be one of its chief attractions because a convention is the most realistic opportunity to fix them.

But the plural office holding problem is merely one of many procedural issues that a constitutional convention could fix. Instead of New York’s past practice of making procedural concerns an objection to calling a convention, they should be one of its chief attractions because a convention is the most realistic opportunity to fix them.

Consider what is at stake. A constitutional convention is the only democratic mechanism New Yorkers have to introduce constitutional amendments that aren’t in the institutional self-interest of the Legislature. That’s far too important a democratic function—a function that implements the people’s most fundamental right, the right to alter their constitution—to allow easily fixable problems to serve as an excuse for preserving the status quo.

Fixing the problems would require a genuine concern for future generations of New Yorkers—something the public and our leaders often profess but rarely do. The question is not merely what the convention New Yorkers would call in 2017 could do to create tangible benefits for our generation, but how that convention could improve future conventions a generation or more hence, when the politicians of today will have left office.

It turns out that democratic theorists think very highly of designing democratic institutions when those doing the designing cannot know whether the rules they design will benefit themselves at the expense of others. For example, you don’t want politicians to design presidential rules of succession after a president has died and they know which specific politicians will benefit from a given succession rule. Under such a “veil of ignorance,” as democratic theorists label it, delegates can act with the greatest degree of civic virtue.

Paradoxically, then, the set of procedural problems convention opponents use to disparage conventions should actually be one of the best reasons to call one.

Fixing the procedural problems should be a major priority of the governor’s commission not merely because it wants to submit its recommendations to the Legislature, but because it ultimately wants to submit them to the convention, which should be spurred on, not hindered, by the Legislature’s obstreperousness. Coming up with the right policies for New York—not merely what is politically feasible given expected Legislature opposition—should be the commission’s goal.

***

J.H. Snider, the president of iSolon.org, is the editor of The New York State Constitutional Convention Clearinghouse and author of Does the World Really Belong to the Living? The Decline of the Constitutional Convention in New York and Other US States, 1776–2015.

***

Have an op-ed idea or submission for Gotham Gazette? Email This email address is being protected from spambots. You need JavaScript enabled to view it.

In a previous column for Gotham Gazette, Snider called for Gov. Cuomo to create a preparatory commission: Preparing for New York's Next Constitutional Convention Referendum, June 4, 2015.

DOE Language Access Expansion Builds Bridges to City Families

Steven Choi, the author

For years, advocates and community based organizations have urged the New York City Department of Education to increase translation and interpretation services to public school parents and guardians with limited English proficiency. Last week, I was honored to join schools Chancellor Carmen Fariña, a true champion for the immigrant community to announce a series of initiatives aimed at easing language access for parents in schools.

Immigrant families face tremendous obstacles – speaking to their child's teacher or principal should not be one of them. With nearly half of public school students – almost half a million families – speaking a language other than English at home, it is essential that these families have the ability to participate in their children's school lives. That's why the New York Immigration Coalition and our Education Collaborative of member organizations representing Asian, Arab, Caribbean, African, Latino, and other immigrant families, launched our "Build the Bridge" campaign that advocated for increased translation and interpretation for immigrant parents.

And we are grateful that the DOE has stepped up and heard our calls. The city's language access expansion efforts are a significant step that will help notably reduce language gaps in our schools. The expansion includes the creation of nine new full-time positions in the Borough Field Support Centers and Affinity Groups that will determine the specific needs of each school, and build the necessary supports so that parents receive quality translation and interpretation services.

The expansion also includes new direct access to over-the-phone interpreters available after 5 p.m. In the past, schools had to contact the Translation and Interpretation Unit, which then connected the call – a step that has been eliminated. This will help reduce wait time for an interpreter, and allow teachers and staff to call non-English speaking families after business hours. Interpreters are available in 200 languages. In addition, starting this month, members of the Citywide and Community Education Councils will also receive additional language support. We want our elected parent leaders to be representative of our diverse school system and want to make sure they are able to communicate among themselves and with others no matter the language they speak.

Having the ability to communicate with parents in a language they understand and in a timely fashion is key to the DOE's work. We will keep up our efforts to ensure that immigrant students and parents are provided with culturally competent services to further strengthen this bridge to immigrant families that the DOE, with help and support from advocates, has built. We celebrate this groundbreaking accomplishment and thank Chancellor Fariña and the DOE for their continued efforts to improve services for immigrant families all across our great city.

***

by Steven Choi is Executive Director of New York Immigration Coalition. On Twitter @stevechoinyic & @thenyic.

***

Have an op-ed idea or submission for Gotham Gazette? E-mail editor Ben Max: This email address is being protected from spambots. You need JavaScript enabled to view it.

Move Martin Luther King Day to November

The Obama family visits Dr. King's memorial (White House Photo by Chuck Kennedy)

In 1982, President Reagan signed the law that established a federal holiday to honor Martin Luther King Jr. Because Dr. King's birthday was in January, the authors of the bill thought it made sense for his holiday to be in January as well.

Almost 25 years later, it's time to ask if they got this right. Because schools are closed on Martin Luther King Day, most children likely see his holiday as a break from the classroom rather than an opportunity to learn about Dr. King. Those adults who have a day of paid vacation are likewise not likely to spend it honoring the civil rights leader. What seemed like a fitting tribute to this great American when it was first proposed now seems sorely inadequate.

Without Dr. King, there's no telling when (or if) Congress would have passed either the Civil Rights Act or the Voting Rights Act. Because of these historic laws, the widespread discrimination that was being practiced throughout much of the country was prohibited, and the voting rights of African-Americans and others were finally protected. It is hard to overstate the effect of Dr. King's efforts. In Mississippi-- just to take one example-- voter turnout among African-Americans increased from six percent in 1964 to almost 60 percent by the end of that decade. Throughout the nation, the work of Dr. King and countless others within the civil rights movement helped advance legal and political equality for millions.

Dr. King's heroism helped accomplish a great deal, but his work is far from finished. Since the 1960s, voter turnout is down significantly, especially in non-presidential election years. In the 1966 midterm elections, 48.7 percent of the voting-eligible population cast ballots. In 2014, just 35.9 percent did. While many creative ideas for increasing voter turnout are offered every election season, making it easier for people to get to the polls would be an important step in the right direction.

By moving Martin Luther King Day to election day, we would finally make election day a federal holiday and instantly give millions of Americans more time to vote. The cost of making this switch would be modest, since it would simply involve moving an existing federal holiday, not creating a new one.

It's hard to imagine that Dr. King or his family would be against such a plan. More people would be able to participate in the democratic process, and every person stepping into the voting booth on election day would be honoring his legacy. King would get the holiday he deserves.

***

by John Martin, Republican District Leader, 81st Assembly District.