After Silver: Legal Reform is Ethics Reform

The author, Thomas Stebbins

For decades it was an open secret in Albany that the New York Assembly was functionally controlled by the trial lawyers. Sheldon Silver, the former Assembly Speaker, was known to have a lucrative "of counsel" position with the powerhouse trial lawyer firm Weitz & Luxenberg, and most Albany insiders believed that Mr. Silver would not do anything to jeopardize that income. Governor Cuomo himself stated that the trial lawyers were the "single most powerful political force in Albany," no doubt in partial reference to Mr. Silver's position as an employee at a trial lawyer firm.

With the trial and subsequent conviction of Mr. Silver on corruption charges, we now know that the former speaker did virtually no real legal work to earn his "of counsel" income. What he did do was carry the legislative water for the trial lawyers, and we as New Yorkers are left with a state ravaged by lawsuits and litigation.

New York has the highest medical liability payouts in the nation, by a wide margin – even higher than California, which has nearly five times the population. The difference is that California passed meaningful reforms to control medical liability costs, reforms that had no chance in Sheldon Silver's Assembly.

These runaway medical insurance costs are more than a financial issue, they are also an issue of access to healthcare. Hospitals across New York City have been closing at an alarming rate, in large part due to the cost of medical liability insurance. Some hospitals are "going naked" and foregoing insurance entirely, just to keep the doors open. The access to care issue extends upstate as well – at least eight New York counties have no OBGYN services at all.

New York also has the highest construction insurance costs in the nation, due to the odious so-called "Scaffold Law," which Mr. Silver cravenly defended.

The oddly-named law has little to do with scaffolds. What it does is hold contractors and property owners absolutely liable in a lawsuit for workers' injuries even if, in the words of the court, they had "nothing to do with the plaintiff's accident."

New York is the only state to apply absolute liability to contractors. In 2014, Mr. Silver proudly shut down Scaffold Law reforms that would have put our legal system in line with the rest of the country by creating a standard where negligence is proportionate to fault. Silver stymied this common sense reform despite findings that the law cost the state government $785 million a year and corresponds with an increase in injuries. In the wake of his corruption conviction, New Yorkers are right to wonder if Mr. Silver blocked Scaffold Law reform on behalf of his trial lawyer employers.

At the center of U.S. Attorney Preet Bahara's case against Mr. Silver was a referral scheme regarding asbestos plaintiffs. It is no surprise that, given Mr. Silver's control over state government and profit from asbestos lawsuits, New York's asbestos courts were recently rated the worst in the nation, routinely paying out three times the national average. In the aftermath of Silver's arrest it was reported that Mr. Silver's employers, Weitz & Luxenberg, received priority access to juries for asbestos cases. In a particularly brazen conflict of interest, Mr. Silver appointed Arthur Luxenberg, a partner at the firm, to the judicial screening committee, while claiming there was no conflict of interest at all.

We can fix this.

Albany can undo the years of corruption under Sheldon Silver by passing meaningful legal reforms. First, we can enact reasonable controls on medical liability payouts, as California has done, and impose higher standards for the expert witnesses in medical cases. Podiatrists should not be allowed to testify in neurosurgery cases.

Second, we should reform the outdated Scaffold Law to the common sense and widely used standard of comparative negligence. No law symbolizes the corruption of the Sheldon Silver era more than a law that holds contractors and property owners absolutely liable under nearly any circumstance. In doing so we could save hundreds of millions of dollars a year and reinvest that money in schools, roads, and bridges.

Lastly, we need to open up the asbestos trusts to transparency. Currently, plaintiffs are able to sue asbestos trusts, potentially recover millions, and then turn around and sue solvent companies for the same injuries. Because the trusts are not open to transparency, plaintiffs can allege entirely different sets of facts with little fear of discovery. In a recent case against the New York company Garlock Sealing Technologies, the judge forced discovery on the asbestos trusts cases and found fraud in 13 of the 13 cases the court reviewed. Opening the trusts to transparency would go a long way to ensure the funds are reserved for those who are legitimately injured as intended.

It is a new day in Albany. With these changes and more the New York legislature can show us that they work for New Yorkers, not the trial lawyers.

***

Thomas B. Stebbins is Executive Director of the Lawsuit Reform Alliance of New York

***

Have an op-ed idea or submission for Gotham Gazette? E-mail editor Ben Max: This email address is being protected from spambots. You need JavaScript enabled to view it.

@GothamGazette

Let's Be Prepared for America's Biggest Corporate Takeover

Presidents Barack Obama and George W. Bush, via White House archives

Imagine taking over an enterprise with 4 million employees and an annual budget of more than $3 trillion dollars. What if on your first day as CEO, you had to operate without more than 1,000 of your top leaders, faced global emergencies requiring immediate attention and had an agenda dependent on multiple, time-consuming votes by your board of directors?

That's exactly what will happen when the next president takes office on January 20, 2017. And it is why we must prepare better for this presidential transition than we have for any prior.

The new president will inevitably need to deal with an unexpected international crisis, pressing economic issues and many controversies, while simultaneously having to make some 4,000 political appointments, including nominees for about 1,000 key management and policy positions that require Senate confirmation. The new chief executive will have to build relationships with world leaders, take immediate control of the national security and financial sectors, pursue a brand new agenda that requires congressional approval and manage a huge, complex enterprise.

There is an expectation that the nation's newly elected chief executive will hit the ground running, but the transition of power and knowledge from one president to another is often rushed, inefficient, overwhelming, and fraught with risk. Being ready to govern requires hard work and many months of preparation that must start well before Election Day. Candidates must simultaneously campaign to win and prepare to govern if they expect to be effective.

The 2008-09 Bush to Obama transition was one of the best in modern history – with both sides understanding that national security and economic conditions required them to work together in unprecedented ways. But it was only as successful as it was because of the vision and goodwill of the leaders involved; we need a system that is not at the mercy of good intentions, but one that enhances rather than diminishes the capacity of our government to function at a high level.

On December 9, the Manhattan Chamber of Commerce will team up with the nonprofit, nonpartisan Partnership for Public Service to host an event about why the presidential transition matters to the business community, and how this often incomplete and chaotic process can be fixed so that the next chief executive will be ready to govern on day one.

The Partnership for Public Service has created a Ready to Govern initiative designed to get the presidential campaigns to seriously think about standing up transition operations as early as the spring of 2016. This will require designating staff and resources to map out personnel and policy strategies, getting up to speed on the work of more than 100 agencies, developing a management agenda and coordinating with the Obama administration for the transfer of power and responsibility.

As citizens, business leaders want a competent and high-performing government. There can be disagreements about the size and role of government, but there should be absolute agreement that whatever government does, it should do well.

From the business side of the equation, executives need federal agencies to be responsive, and they want some certainty, not ambiguity, about economic policies as well as federal programs and regulations so that they can plan and make the hard decisions that will affect their bottom lines and employees.

If a new administration is unprepared or cannot get its top political appointees in place quickly, it is inevitable that critical decisions on matters small and large will be put on hold, problems will fester and businesses will lose both time and money. All too often, a new president has been in office for a year or more before a full leadership team is in place – and that dearth of leadership has contributed to government dysfunction and ineffectiveness.

If a new administration fails to pay close attention during the transition to choosing capable leaders and planning for effective management - two issues the business community knows a great deal about - policy implementation will suffer and that will affect us all.

The presidential transition cannot be left to chance. Too much is at stake. The candidates must engage in extensive planning, Congress must devote resources and confirm appointees quickly, and the private sector should contribute its expertise when possible and hold those seeking the presidency accountable for preparing to govern.

We may not agree on who should be president, but we surely can agree that better processes and mechanisms must be put in place to ensure that our new government gets set up as quickly and effectively as possible.

***

Ken Biberaj is the chairman of the Manhattan Chamber of Commerce and David Eagles is director of Presidential Transitions for the nonprofit, nonpartisan Partnership for Public Service.

***

Have an op-ed idea or submission for Gotham Gazette? E-mail editor Ben Max: This email address is being protected from spambots. You need JavaScript enabled to view it.

Ethical Treatment of Our Homeless Neighbors

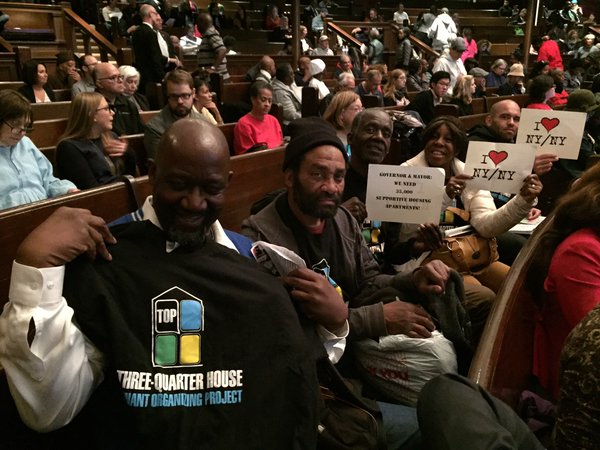

At a recent NY/NY event at New York Society for Ethical Culture, via @TOPnyc

I usually approach the New York Society for Ethical Culture, where I serve as clergy leader, from Central Park West and look across the street from the park at the words carved into stone on the corner of our meeting house: "Dedicated to the ever-increasing knowledge and practice and love of the right."

Today "the right" is used to identify a socially conservative political stance, but in 1910, when these words were inscribed, it referred to ethics and a community determined to do the right thing in challenging times. Since founding the Society in 1876, members have sought ways to make the world a better place for everyone, beginning with improving living conditions in tenement housing and forming settlement houses that built affordable housing.

Nearly 140 years later, we still live in challenging times and continue our commitment to treating the homeless as our neighbors and working for affordable housing. Today, we have many partners in the Interfaith Assembly on Homelessness and Affordable Housing. In addition to providing shelter for homeless women for over thirty years, the Society hosts events that gather advocates from across the city and state to work in concert for affordable housing.

The latest event, held on October 23, "Campaign 4 NY/NY Housing," called upon Governor Cuomo and Mayor de Blasio to work together and with the more than 200 state and local organizations calling for 30,000 new units of supportive housing over the next ten years for our most vulnerable neighbors: the homeless, now about 60,000 people who sleep in city shelters or on city streets every night. This statistic includes over 14,000 families with nearly 24,000 children; and it has reached the highest levels since The Great Depression of the 1930s.

How did this happen? Research compiled by the Coalition for the Homeless from data collected by the city Department of Homeless Services and Human Resources Administration shows that the primary cause of homelessness is lack of affordable housing, triggered by eviction and job loss, severely overcrowded and hazardous housing conditions, domestic violence, and serious mental health disorders. This social "perfect storm" has put a strain on the resources of private and public organizations throughout the city, especially in Manhattan, which holds nearly 60 percent of our unsheltered homeless.

How do we address this community reality? Mayor de Blasio, whose administration recently announced a plan to create 15,000 supportive housing units over fifteen years at a cost of $3 billion, will face pushback from neighborhood leaders who oppose the siting of those units. But, it is absolutely essential. Negotiations with Governor Cuomo over a new "New York/New York" deal, the much-anticipated fourth city-state supportive housing plan, are at an impasse. Local advocates, including we clergy in the Interfaith Assembly, are frustrated with the de Blasio-Cuomo feud and have written to both politicians imploring them to stop playing politics and start acting like the leaders we elected them to be. This is an ethical issue that demands immediate and non-egotistical action.

In the meantime, how can we be the good neighbors that so many of us want to be? NYPD Commissioner Bratton has urged New Yorkers not to give money to homeless people living on the streets, and Mayor de Blasio has said that the best way to help is to donate to nonprofit organizations serving homeless people. I agree, we should donate to shelters and organizations, and I hope that more people will volunteer at shelters, including ours. But I see no harm in making a direct and personal donation to individuals. Offering money can be awkward, but offering a piece of fruit, a wrapped sandwich, or a coupon to a restaurant is appreciated. We can also provide information about local sites that offer meals and hot showers. Interfaith Assembly on Homelessness and Housing offers a helpful resource that can be referenced, printed, or circulated by email or on social media.

The most important way of helping is to see others as people worthy of dignity and respect. Bear in mind that many people who live in shelters are employed, but their income isn't enough to cover housing; they are not lazy and useless.

When I leave the Society for Ethical Culture's meeting house, I always stop to read at least one passage from the "sacred" text mounted on the north wall of our lobby: the Universal Declaration of Human Rights. It is a document that set out, for the first time, fundamental human rights to be universally protected, and was proclaimed by the United Nations General Assembly in Paris on December 10, 1948, in the wake of World War II.

Today I read very closely Article 25(1): "Everyone has the right to a standard of living adequate for the health and well-being of himself and of his family, including food, clothing, housing and medical care and necessary social services, and the right to security in the event of unemployment, sickness, disability, widowhood, old age or other lack of livelihood in circumstances beyond his control."

No doubt some New Yorkers have become numb to seeing homeless people on our streets. Homelessness in our city has nearly doubled in the last decade, and "compassion fatigue" can occur, especially if we feel there is nothing we can do to make a difference. But when we acknowledge our common humanity, encounter people with an open heart and gentle words, educate ourselves about the resources available in our communities, and resolve to act, we can make a real difference in the lives of our neighbors.

***

Dr. Anne Klaeysen is a Leader of the New York Society for Ethical Culture.

***

Have an op-ed idea or submission for Gotham Gazette? E-mail editor Ben Max: This email address is being protected from spambots. You need JavaScript enabled to view it.