Birth of the Park

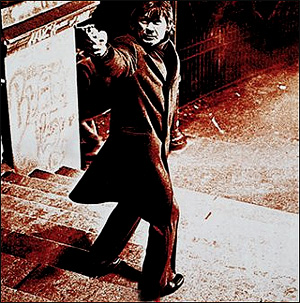

Late 19th century, photographer unknown.

From "Central Park in Blue" at the Museum of the City of New York, one of several current exhibition about the Park.

Central Park at 150

.........................

Overview:

Still a Pioneer

Art in the Park:

Our Project for the Park by Christo and Jeanne-Claude

History:

» Birth of the Park

» Death of Seneca Village

My Backyard:

» Dancing in the Park

» An Escape from Reality

Crime:

Taking Back the Park from Crime

Reading:

Books About Central Park

Manhattan real estate is rather precious, so this was a momentous decision that took a great deal of political will. It required a general consensus among the population and the politicians that there had to be a park.

The need for a great central park in New York City goes back to the beginning of the 19th century and the creation of the grid plan in Manhattan. In 1807, the city was on the cusp of growth. Astute city builders knew that Manhattan's location, the quality of it port, the proximity of the Hudson River, and the idea that there would be an Erie Canal, would make this the city of commerce in America and that growth would be extraordinarily rapid.

The challenge was how to plan for it, and the planners came up with a very practical and logical scheme: 12 broad, north-south avenues and 155 narrow, east-west streets from Houston to 155th Street. This plan was imposed upon a very irregular, rocky, somewhat hilly landscape but had nothing to do with any of the natural topographical features. The only open of any size was between 23rd and 34th streets. Called "The Parade," it was a place for the local militias to exercise. By 1830 this park was gone, and because of great pressures of real estate development, all public land had disappeared.

Even the most stalwart builder knew that the city was going to require some sort of a park for peace and safety. People were beginning to think there had to be some reaction to the total control of Manhattan by the grid-planning of 1811. Andrew Jackson Downing, the editor of a very important magazine called The Horticulturalist, who had the ear of lots of Americans, started editorializing that New York needed a park of at least 500 acres. William Cullen Bryant, a leading poet and journalist, also editorialized about the need for major park.

By the 1851 mayoral elections, both the Democrats and the Republicans campaigned for a public park. The question was where, how and what is it going to look like.

Two locations were considered. One was Jones' Wood, a plot of land on the East River that was about 150 acres and pleasantly landscaped. You could easily put up a sign that said "New York Park," let the people in, and you would have been done. But it was not central, it only would have served a certain area, and it was not big enough. People like Andrew Jackson Downing said, "This is inadequate; it will not do."

The other choice was the site that we know today. It was already the site of the first great public works project in New York City, which was the Croton Water System. In the mid-1830s, the city found that if it did not come up with a municipal water supply that was adequate and sanitary, the city could not grow.

So a huge public works project was completed in 1842. Water from the Croton River in Westchester County was brought 42 miles across the East River into the Receiving Reservoir between 6th and 7th avenues, between 79th and 86th streets. From there it went down to 42nd Street and 5th Avenue to the Distributing Reservoir on the site of what is now the New York Public Library. By 1853, the managers of the Croton System began to survey for a huge North Reservoir, which still exists today north of 86th street.

There was a compelling logic that if you were going to take land from the private market for a park it should be tied in with the two reservoirs so the land between them would not be wasted. This was the anchor upon which the park was based. The receiving reservoir, which was filled in in the 1930s, is now the Great Lawn -- the park’s geographical center.

In 1853, everyone had agreed that the land around the reservoirs would be the place for the park. It would be about 848 acres, big enough to suit the requirements of landscape architects.

But it was a very unprepossessing piece of real estate. No one would have chosen it for its beauty or charm. It was rough, rocky and swampy, and it required a vast amount of work to make it into what it is today.

A board of commissioners for the park was established and hired a very accomplished engineer named Egbert Viele. He surveyed the area of the new park and did a pen-and ink drawing in 1855 of a design for a drainage system.

Meanwhile, in 1852, A.J. Downing had died saving victims of a tragic accident that occurred when two steamboats got into a race on the Hudson River. Just the year before he had brought back from England a young man named Calvert Vaux, a trained architect. Vaux looked at Viele’s design, which had been accepted, and said, “This is terrible. This is not adequate. Downing would not approve.” He began politicking behind the scenes and persuaded the commissioners to drop the plan and have an open competition.

The competition was announced in 1857, and 33 proposals were submitted in the spring of 1858. Twelve of the 33 were done by people who were already involved with the creation of the park. Few of these proposals have survived.

The proposals had to honor and incorporate 10 requirements. There had to be a playground, a parade ground, a cricket ground, a flower garden and a group of buildings for exhibitions.

How did Calvert Vaux, having started the competition, get into it himself? He realized he did not have the ability to do the whole thing himself. He did not know the topography well enough. And he also knew that if he were lucky enough to win, he would not have the ability to execute the plan. So he found Frederick Olmsted, who had lost all his money by investing in a publishing business and then ended up as superintendent of Central Park in 1857. Olmsted was working everyday in the park on horseback and knew everything about it.

Vaux persuaded Olmsted to join him in drafting a proposal for this competition. The two of them worked together every evening through the winter of 1857. Their entry was the last submission, and they won.

Vaux and Olmsted included all the things that the competition required: a parade ground, a playground, a flower garden, a conservatory, a museum area, cross streets, a skating park. But all of this was of no real interest to Vaux and Olmsted. What they saw was an opportunity to transform this piece of raw, rocky, narrow, very unsympathetic nature. They were given the worst possible playing deck of cards, the most unpromising piece of land, and that forced them to think outside the box.

The idea was to separate this piece of nature from the city entirely. Once you enter the park, you do not want the city to be included.

Vaux and Olmsted proposed great open areas, which they saw as beautiful landscapes; they saw it as a great, English, stately home meadow. This required major transformations of nature. Ten million cartloads of earth and rock were moved. Far more than simply creating a park, it was transforming nature into a work of art.

Vaux and Olmsted got the commission and went ahead with it. Theirs was a great partnership because they were complimentary in their talents.Vaux did everything architecturally. He designed all the buildings and the 35 or 36 bridges, most of which survive today and are the great glories of Central Park. The original design had only a half dozen bridges. But shortly after the plan was accepted, commissioner August Belmont said there needed to be bridle paths in the park. That requirement meant 35 or 36 bridges.

The biggest architectural component of the park was the Bethesda Terrace, which survives today and was one of the grandest public buildings in New York. It is virtually invisible unless you see it from the right angle; the point that Vaux was making was that architecture should always be subsidiary to nature in Central Park. And that may be why Vaux has, historically, been second fiddle to Olmsted. Vaux was not as charismatic, but he was crucial to the Central Park’s creation.

Central Park cost about $10.5 million. This was big money at the time -- the land alone cost more than $1.5 million. And in October 1857, times were really tough. How did they win approval for this huge public works projects.

The economic panic was a blessing in disguise because the politicians wanted to employ all these people who were out of work. Olmsted had up to 4,000 people on his payroll in 1859-61. It was not until 1862 and the Civil War draft that the numbers went down. Between 1858 and 1861, virtually the entire park up to 79th street, the most complicated part, was built. It was an extraordinarily rapid achievement using the best materials and no shortcuts.

The park was immensely popular from day one, and its constituency was as varied as the city -- and as varied as it is today.

Morrison H. Heckscher is the Lawrence A. Fleischman chairman of the American Wing at the Metropolitan Museum of Art. This is adapted from a lecture he gave in conjunction with the museum’s exhibition, “Central Park: A Sesquicentennial Celebration,” which runs until September 28, 2003.

Taking Back the Park from Crime

Central Park at 150

.........................

Overview:

Still a Pioneer

Art in the Park:

Our Project for the Park by Christo and Jeanne-Claude

History:

» Birth of the Park

» Death of Seneca Village

My Backyard:

» Dancing in the Park

» An Escape from Reality

Crime:

Taking Back the Park from Crime

Reading:

Books About Central Park

Kane's murder was the first of the homicides whose inherent brutality seemed incalculably worsened by their senselessness -- and their location in the Eden of Central Park. In fact, journalists since the 1930s have used incidents in Central Park as powerful symbols for urban crime in general.

The truth is, though, that, like the city itself, the park has been safe for most of its history -- until the "rogue crime wave," to use historian Eric Monkkonen's words, that engulfed New York between 1958 and 1991 and found Central Park to be a particularly tractable host.

And the first chapter in New York City's much heralded, triumphant campaign against that crime wave began in Central Park in 1980. Years before Rudy Giuliani was elected mayor or Bill Bratton appointed police commissioner, the team of officials overseeing Central Park devised a strategy for making Central Park safe again.

CRIME WAVE

In 1965, Robert Lowell published his poem "Central Park," which displayed the 1960s' odd combination of fear of violent crime and contempt for cops:

"We beg delinquents for our life.

Behind each bush, perhaps a knife;

each landscaped crag, each flowering

shrub,

hides a policeman with a club."

The design elements that helped make the park a refuge from the city -- secluded woodlands, hidden coves, paths that curve and dip from sight, Lowell's flowering shrubs -- also made the park hard to protect or patrol. Central Park's fame and beauty made it a prized site for concerts, protests, marches, rallies and celebrations. But the huge crowds also attracted crime.

These two factors, combined with public and police tolerance of so-called petty crime during the 1960s and 1970s, led to a wave of muggings and vandalism in the park that New Yorkers noticed -- and feared. Faced with public concern, park officials during the Wagner administration mowed down shrubs and removed trees from areas where muggers were thought to lurk.

And more draconian proposals were also put forward. Wagner's parks commissioner, Robert Moses, suggested building a senior center in the wooded Ramble in order to halt both gay sexual encounters and violent assaults on gay men.

The idea of the park as sanctuary faded as crime soared. In the 1960s and 1970s, felonies in the park surely averaged at least 800 to 900 a year; we cannot know for sure because it was so difficult for victims to report crime. The park had almost no functioning call boxes or public phones. Reaching the police precinct house in the park by foot was nearly impossible from many sections, even the adjacent Great Lawn. And those intrepid victims who managed to make it to the precinct house were often discouraged from filing criminal complaints.

WAS CENTRAL PARK EVER THAT DANGEROUS?

Many commentators today note that, for some time, the Central Park precinct has had the lowest crime figures in the city. Last year, for example, Central Park had only one of the city's 584 murders, and only 5 of the city's 2,024 rapes. Indeed, for all of 2002, Central Park (PDF Format) had only 132 major crimes -- a 72 percent decrease from 1993. The city as a whole had 153,682 major crimes in 2002 -- or a 64 percent decrease from 1993.

But comparing Central Park to other precincts isn't really fair. It not only has no resident population, making the calculation of crime rates impossible, it is closed at night, while all other precincts remain open for business, and crime.

Central Park's crime numbers are very low, which is wonderful. But in important ways, the problem never was simply the numbers of major crimes. Instead, Central Park has been plagued by three distinct crime problems.

First, it has always attracted heinous crimes that became highly publicized and discussed because of Central Park's symbolic importance, and its location in the middle of New York City, the nation's media capital. The three national television networks, for example, were headquartered within walking distance of the park. Their broadcasts, as well as Johnny Carson's regular nightly attacks, probably exaggerated the extent of Central Park's crime. But there is also no doubt that crime in the park was a real problem.

Second, public events such as concerts or parades have often resulted in rampages by young men. The low point of the park's early restoration occurred on July 21, 1983 -- exactly 20 years ago -- when, following a poorly organized concert by Diana Ross, hundreds of young men tore through the park and its neighboring blocks, assaulting anyone they encountered. A family that had just flown in from Paris for vacation told the New York Post that they had been assaulted and robbed by a gang of 20 teenagers. When, bleeding and bruised, they asked a cop for help, he told them, "That's life in the big city," and walked away.

Warner LeRoy, the owner of the Tavern on the Green, said that dozens of teenagers climbed onto the restaurant's roof and leapt down to the interior patio, where patrons were eating. They jumped on tables, stabbed diners, and stole purses and bags, before swarming back over the patio walls. Known as "the night Central Park got mugged," July 21 resulted in very few arrests -- or recorded crimes.

The third kind of troubling Central Park crime is the vast area of relatively minor crime, such as purse snatchings and bike thefts (before bikes cost thousands of dollars). A poll in 1983 found that over 65 percent of regular park users had experienced some "encounter" with crime in the park. Less than 5 percent said they had reported the incidents, assuming the cops would just dismiss them anyway. And seven percent of regular users said that they carried a weapon in Central Park.

MAKING CENTRAL PARK SAFE AGAIN

The team that began Central Park's rescue in 1980 included Parks Commissioner Gordon Davis, Central Park administrator Elizabeth Barlow (Rogers) and the captain of the Central Park Precinct, Carl Jonasch. They saw the safety of Central Park users, and of the park’s physical plant, as essential to the park's renaissance. They were practical people. No amount of restoration was going to work if the park was dangerous. Donors would not give millions of dollars to restore park treasures that were just going to be vandalized all over again. Nor would donors be enthusiastic if they and their fellow New Yorkers were afraid to enter the park to see the fruits of their gifts. The park had to be revived as the haven that Frederick Law Olmsted and Calvert Vaux had envisioned in the 19th century.

The team faced many impediments, an ominous one being that the Central Park precinct itself was a sorry mess. Housed in a badly maintained converted stable that reeked of urine on humid days, Central Park cops were often a demoralized, tired lot. Ambitious cops avoided being assigned to Central Park, which offered few chances for career-making arrests. Instead, the precinct attracted many who were eager to pass their final years before retirement peaceably. When they had to patrol, they stuck to their cars. There was not much pressure to get out of the cars since the 911 system, implemented in 1972, had centralized dispatch, removing it from the precinct.

Jonasch set out to change things. He was an athlete and one of the first cops to run in the park. He wanted cops to know the park as users rather than as drivers, a revolutionary idea. And he wanted the cops to get out of their cars and patrol on foot or scooters. He met with serious resistance.

But at the same time, Commissioner Davis started the ranger program, creating a uniformed force that would patrol the park and educate park users, concentrating on the quality-of-life issues that cops deemed beneath them. In 1982, Davis added Park Enforcement Patrol (PEP) officers, who could issue summonses for infractions of park rules. Both the rangers and PEP officers visibly patrolled restored sections of the park, enforcing high and previously unknown standards of behavior, such as no ball-playing on Sheep Meadow.

But the conceptual breakthrough in making Central Park safer was the now-familiar but then brand-new broken-windows theory of policing. Harvard professor James Q. Wilson said that cops underestimated the seriousness of disorder, whether the physical disorder apparent in vandalism, graffiti and neglect or the disorder of people behaving badly. The police had to take small signs of disorder seriously and deal with them. That could mean handling small-time offenders, confronting physical disorder or some combination of both. Police could not dismiss disorder as "petty" because petty had a way of growing serious.

Just after the March 1982 publication of his Atlantic Monthly article propounding this idea, Wilson gave a lecture to New York police brass about implementing his theory of policing. Jonasch argued this new approach would be ideal for Central Park.

Crime was still high in 1982, over 700 robberies and 9 murders, when Captain Jonasch set the new strategy for the park. Even as the park seemed to get safer every year, however, horrible crimes punctured its serenity.

In May 1985, gangs of teenagers attacked participants in a March of Dimes Walkathon. NYPD Captain Ray Vignola called them "jackals on the velt." In July 1986, Officer Steven McDonald was shot, and paralyzed, when he stopped a group of teenagers on the East Drive In April 1989, the Central Park Jogger (now known to be Trisha Meili) was beaten, raped and left for dead. On the same night, dozens of youths rampaged through the park, assaulting and robbing park users.

Since then Central Park has reflected the overall drop in crime in the city, although crime has not disappeared entirely. The park was, for example, the scene of attacks on women following the Puerto Rican day parade in June 2000. The lessons from Central Park are pretty clear. It is now probably the safest and the most beautifully restored of the world's great parks. But only constant vigilance will keep it that way.

Julia Vitullo-Martin, who writes Gotham Gazette’s topic page on crime, is a long-time editor and writer on urban affairs, and the co-author of a study on Central Park security conducted for the Central Park Conservancy in the early 1980's.

Central Park at 150

Central Park at 150

.........................

Overview:

Still a Pioneer

Art in the Park:

Our Project for the Park by Christo and Jeanne-Claude

History:

» Birth of the Park

» Death of Seneca Village

My Backyard:

» Dancing in the Park

» An Escape from Reality

Crime:

Taking Back the Park from Crime

Reading:

Books About Central Park

When New York City decided 150 years ago to build Central Park, it launched a project that became the model for city parks throughout the country. A major undertaking for the city, as Morrison Heckscher of the Metropolitan Museum of Art points out (“Birth of the Park”), Central Park was both a masterpiece of landscape art and a social experiment, a place where people from all walks of life could come together to enjoy a respite from the strains of urban life. After the park opened in the winter of 1858, every city in the country wanted its own version, and the American parks movement was born.

Today Central Park is cherished by the many New Yorkers who come to the park to escape from the rest of the city ("An Escape from Reality" By Sarah P. Lustbader), to appreciate nature, to form new communities (“Dancing in the Park” by Kendall Williams) or to make art (“Our Project For The Park,” by Christo and Jeanne-Claude). And Central Park remains a national model. The park’s rebirth over the last two decades, accompanied by a dramatic drop in crime within its boundaries ("Taking Back the Park from Crime" by Julia Vitullo-Martin) has shown other cities how they can restore their public landscapes. The Central Park Conservancy, begun by Betsy Barlow Rogers in 1980, pioneered the concept of a non-profit community organization raising funds and working with government to fix up and maintain a public park. Parks throughout the city and country -- even the national parks -- have adopted this idea of public-private partnership.

The very success of the Central Park model, however, raises some concerns. The reliance on private funding could weaken the government's traditional role in maintaining public space and ultimately reduce the opportunity for all citizens to enjoy it. Although Central Park has remained the quintessential public space, in Bryant Park, for example, private events held in the park temporarily keep much of the public out.

The reliance on private funding could leave the city with a two-tier park system. Individuals and corporations are most likely to donate to a park they care about, favoring parks in affluent areas. Despite efforts to provide private funds for the rest of the system, such as the non-profit City Parks Foundation, parks in poor neighborhoods, particularly outside Manhattan, could be left to depend on dwindling public dollars.

The activism of the Central Park Conservancy has fostered beautifully maintained grounds and funded many public performances and educational programs, "setting a standard to be achieved for the entire city park system," said Christian DiPalermo, director of New Yorkers for Parks. This has raised New Yorkers' expectations for all of the city’s parks. "You can't have Central Park with a completely different set of policies as the rest of the system," said Ethan Carr, a visiting professor in the Bard Graduate Center's landscape history program. But bringing the condition of all parks up to the level of Central Park would require the city to greatly increase its funding for parks, something it did not do even when the economy was thriving.

It is not only in fund raising that Central Park serves as a model. The conservancy, which operates the park under a contract from the city parks department, is in the forefront of park management as well. The conservancy does not just raise money – it runs the park and hires most park employees. The city parks department has ultimate oversight but does not manage Central Park as it does most other city parks.

The restoration of the park has been guided by a master plan, something urban park expert Peter Harnik says is key to a well-run park. And unlike the parks department in New York and many other cities, the conservancy plans for the long-term upkeep of areas that it has restored, protecting its capital investment and minimizing costs in the long run.

The park has had great success with its innovative "zone management" system, where one gardener is responsible for a specific section of the park. The gardener has the authority to enforce rules – such as prohibitions against trampling newly seeded areas, littering or letting dogs run loose – and is someone to whom visitors can complain or report problems. Doug Blonsky, the administrator of the park, said the zone system “works wonderfully in developing relationships with the community."

Any controversy within Central Park’s boundaries – be it crime, turning a blind eye to wine drinkers in the park while ticketing beer drinkers at the beach, or installing a work of art on its walkways -- immediately gains prominence because this is, though not our biggest, our most beloved and most used park. But a century and a half after it was first created, Central Park continues to inspire. The question is whether the New York City park system as a whole can benefit from its example. Ethan Carr said, "If we are going to call Central Park the great success story of American parks in the last 20 years, we have to find out how that can be extended throughout the New York City park system."

Anne Schwartz is the parks columnist for Gotham Gazette