The Education Equality Act

When Catalina Martinez, a Mexican immigrant, first received a notice from her son’s school, she did not think much about it because she didn’t understand what the letter said. But that soon changed after several notices arrived. She became anxious about her son and suspected that he might have a problem.

“I need to understand what is going on with my son, ”Martinez, a mother of four, spoke in Spanish through a translator. “But I don’t really understand English very well.”

Martinez eventually went to her son’s junior high school and found that those notices were sent to let her know that her son had not been attending classes.

“There are thousands of parents like me out there,” she said.

With foreign born residents at an all time high in the city, Martinez is one of more than 25 percent of New York City parents, according to New York Immigration Coalition, who are excluded from participating in their children education because of their language barrier.

But the government is trying to do something about it. Intro 464: The Education Equity Act was introduced in the City Council by council members Hiram Monserrate and David Yassky. The legislation requires the Department of Education to translate documents, such as report cards and notices, into the eight most widely spoken languages-- Spanish, Chinese, Russian, Italian, French, Yiddish, Korean and Polish -- and provide interpretation services for parents who don’t speak English.

With the hope to make their concerns heard, Martinez and other parents gathered recently at City Hall to demand passage of that bill.

“This is the least the city can do for immigrants,” said Andrew Friedman of the Make the Road By Walking, a non-profit group that organized the rally. The group also organized a campaign for children and parents to write postcards to Mayor Michael Bloomberg, City Council Speaker Gifford Miller and education committee chair Eva Moscowitz to urge support of the bill.

Like many other parents, Nabia Duque believed the legislation would help her to be more involved with her kids.

“When I go to the PTA meeting, I don’t understand what happened half of the time,” she said in Spanish through a translator. “I felt so left out and after a while I just got up and left.”

Some parents said some schools tried to help non-English speaking parents but they lack funding and resources to give proper translation services.

“They are using [bilingual] children as translators,” said Vladimir Epststein of the Metropolitan Russian Parents Association. “Most of the time they make a lot of mistakes.”

This year the Department of Education created a new translation and interpretation unit and promised to spend additional $7 million on the program. Citing this new initiative, the department has expressed opposition to the legislation arguing that it is unnecessary and costly.

Friedman argued that the department plan is temporary. “They only promise to spend that $7 million in one year. Intro 464 is much more specific and comprehensive.”

An estimated cost of implementing The Education Equity Act is reportedly $20 million. “If you can find $200 million to fund tax rebate, you can definitely fund the translation,” he said.

Over half of the city council members supported Intro 464 but some Republican councilmembers have asked the mayor to come out publicly against it. So far Mayor Bloomberg has not expressed his position on the bill.

“The act diminishes motivation for parents to learn English and in turn prolongs their time to fully immerse into American society,” said Republican councilmember James Oddo. “There are more than 180 languages spoken in the public schools so the selection of eight to translate is not fair to other groups”

Some parents said that they have been studying English. “I am taking classes,” said a Brooklyn mother Irania Sanchez, “ But I don’t want to wait until my English is perfect to be involved in my daughter’s education.”

An immigrant from Bangkok, Thailand, Chaleampon Ritthichai is the editor of The Citizen.Â

Charge Or Release!

|

When I graduated from Midwood High School a dozen years ago, the community surrounding it represented what is best about the city - the diversity of everyday living - something that was evident each time we ate at the diner at Flatbush Junction with its predominantly African American customers, or walked through the tree-lined streets of the Orthodox Jewish neighborhood, or caught the bus at Little Pakistan on Coney Island Avenue

A decade later, Little Pakistan, one of the communities that make up the neighborhood of Midwood, Brooklyn, has undergone an arresting change. The Pakistani Embassy estimates an exodus of as many as 15,000 within the past few years, with formerly bustling stores reporting a 40 percent drop in business, and mosques once so overcrowded during services that worshippers laid their prayer rugs on the sidewalk now one-third empty on Fridays.

Midwood's residents fled as a direct consequence of the government's new antiterrorism policies. The impact on this one community is part of a larger narrative on the impact of these policies on many lives, in particular those of people guilty of no crime. But this will not end with Midwood's Little Pakistan.

Since 9/11 the government has resurrected an old and disproved formula to violate civil liberties for a temporary sense of security. Widespread ethnic and religious profiling of Arab, Muslim and South Asian men living in the United States, and a relentless attack on immigrants' rights are commonplace today. Thousands of New York City residents have been detained, deported, or interrogated by the federal government.

In New York City, what began as profiling and detentions in Midwood, quickly spread to attacks on other rights and liberties, including the right to freedom of speech, expression, and association guaranteed to us all by the First Amendment. During last summer's Republican National Convention, city officials once again used the national security card to curtail New Yorkers' right to political expression and association. Just some of the tactics used by the police that left a chilling impact on New Yorkers' First Amendment rights include the closing of Central Park to political rallies; the mass arrests of hundreds of innocent individuals; the lengthy detentions of individuals charged with minor violations; and the widespread police videotaping of lawful protest activity.

Particularly disturbing were the cases of hundreds of individuals detained by the police with no access to a judge for excessive periods beyond what's permitted by law. During the Republican National Convention, hundreds of demonstrators were detained for 30, 40, or even 50 hours without arraignment after arrest for protest-related activities. As the months progressed and the overwhelming majority of the 1,800 arrests at the convention were dismissed, advocates began studying the issue and looking for ways to solve the problem once and for all.

That is why the Charge or Release bill is scheduled to be introduced in the City Council this week by Councilmember Bill Perkins. The legislation will address the serious injustice caused by prolonged detention without arraignment -- injustice not limited to immigrants. It is a response to the general attack on civil liberties post-9/11, and to problems faced by communities of color in New York City on a daily basis.

Each month in New York City, thousands of individuals are detained by the police for periods exceeding the 24 hours permitted before seeing a judge. A recent study by the NYCLU and its Bill of Rights Defense Campaign, a project I direct, found that during the months of October and November 2004, more than 16,000 individuals were held for longer than 24 hours. In Bronx County, 62 percent of arrestees were arraigned after 24 hours of detention, in violation of New York case law.

To understand the severity of the issue one must understand that bringing an arrestee before a judge for arraignment is more than a technicality of the law. The arraignment is the first time since the arrest that individuals are formally informed of the charges against them, their right to counsel and their right to seek bail. It is the first time that individuals who have been held for hours incommunicado may finally communicate with their counsel, family and friends.

Adding insult to injury, the majority of those detained in violation of the 24 hour mandate are charged with low level offenses, such as misdemeanors or violations, and would likely face no jail time if convicted. Yet while they wait unnecessarily in often overcrowded detention facilities, many are forced to miss work or school, or must urgently attempt to locate child care. Moreover, the prolonged detention of political demonstrators keeps them from taking part in ongoing protests and discourages others from participating in future demonstrations. This chills our right to freedom of speech and association.

The Charge or Release bill will require that the New York Police Department and the Department of Correction fulfill their arrest processing duties in an expeditious and timely manner to ensure arraignment by a judge within 24 hours of arrest. The bill also provides the New York City Council oversight over the arrest-to-arraignment process. It will create transparency where this is little now. (The bill only addresses problems faced by arrestees in New York City detained by the local police; it does not address the detention of immigrants by the Department of Homeland Security or the FBI, which are federal agencies.)

Future generations will remember the post-9/11 era as a time of great controversies in the United States. It didn't begin this way. Right after 9/11, New Yorkers and people from the across the country were united in their remembrance of the victims of those terrible attacks, and in a resolve to prevent future attacks from happening. Yet today, the post-9/11 era has come to symbolize opportunism and a time when civil liberties are placed in danger by ineffective government measures that do little to protect the nation, yet threaten our core values. The Charge or Release bill will restore some of those rights that have been needlessly lost.

Udi Ofer is the director of the Bill of Rights Defense Campaign for the New York Civil Liberties Union

Â

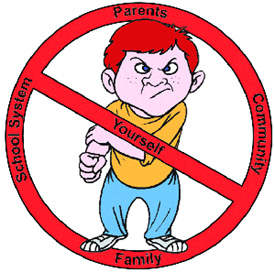

Bully Busting

For Liliya Kane, a young immigrant from Russia, the problems began when she started seventh grade in a New York City public school. Her fellow students pelted her with spitballs and wads of paper, stole her diary and paid a boy to ask her out on a date. "Every day there was something new and something more horrible," Kane said. "I grew to hate everything that had to do with my nationality and my culture. I couldn't bring myself to completely trust anybody."

Kane told of her experiences at a recent City Council hearing. At the same meeting, several Asian high school students described being beaten up by a larger group of African-American teenagers. The lesbian mother of a third grader said classmates ridiculed her daughter, telling her that her parents were "disgusting."

New York City schools officially prohibit bullying, but verbal abuse, taunting, menacing, sexual harassment and physical violence pervade many schools. To confront the problem, the city has opened a high school for gay, lesbian bisexual and transgendered students - a frequent target of school bullies - and City Council passed an anti-bullying bill over Mayor Michael Bloomberg's objections. Now, the mayor refuses to enforce the law. The state has an anti-bullying policy, although legislation aimed at the problem remains stalled in the legislature.

Experts debate which measures work and which don't. But adults no longer dismiss bullying as just part of growing up. Most now agree that harassment wreaks lingering psychological damage, interferes with learning, and can lead to further, sometimes extreme, violence.

FROM TOM BROWN TO HILLARY CLINTON

Fighting, teasing, taunting and arguments are commonplace in schools and on the streets. Bullying, though, according to the Brown University Child and Adolescent Behavior Newsletter, goes beyond simple squabbling or even fist-fighting to entail "a power imbalance between the bully and the target" that can spring from differences in size, strength, skill, popularity or gender. Sexual orientation and race can also be factors. Bullying can range from an outright act -- hitting or insulting -- to more subtle but equally damaging acts such as excluding the victim from the group.

Ironically, the word bully derives from the Dutch word boel, for lover, but by the mid-1600s had come to mean "harasser of the weak." The 1857 novel Tom Brown's School Days depicts Tom's efforts to deal with a cowardly bully at the notorious British Rugby School.

"I was bullied. No one has not been bullied," Marian Wright Edelman, founder and president of the Children's Defense Fund told the Washington Post.

In her autobiography, Hillary Clinton recalls being bullied as a new kid on the block in a Chicago suburb. "Every time I walked out the door, with a bow in my hair and hopeful look on my face, the neighborhood kids would torment me, pushing me, knocking me down and teasing me until I burst into tears and ran back in the house," the senator said. The abuse continued until her mother forced her to go back outside and stand up for herself.

And bullying is not limited to schools - or even to children. An entire institute studies workplace bullying. Domestic abuse is often another term for bullying of children, partners and the elderly.

Some of the opposition to President George W. Bush's nomination of John Bolton as ambassador to the United Nations centers around allegations that Bolton is a bully - or, as former State Department intelligence chief Carl Ford phrased it, a "kiss-up, kick-down sort of a guy."

Other grownups cited as bullies include rapper Eminem - "the bullied boy turned bully," in the words of a Boston Globe critic - California Governor Arnold Schwarzenegger, whose taunts of "girlie men" have become the staple of satire, and Vogue editor Anna Wintour, whose bullying of her staff provide grist for the roman a clef "The Devil Wore Prada."

TAKING ON THE ISSUE

The spate of deadly school shootings beginning in the 1990s helped move bullying from being a personal issue to a social and political one. Of 41 school shooters studied (.pdf) by the Secret Service and the U.S. Department of Education, two-thirds felt persecuted, bullied, threatened, attacked, or injured before the shooting, with many having been the victims of "longstanding and severe bullying and harassment,' according to a study. "It is reasonably clear," psychologist Elliot Aronson wrote, "that a major root cause of the recent school shootings is a school atmosphere that ignores, or implicitly condones, the taunting, rejection, and verbal abuse to which a great many students are subjected."

THINGS TO DOIf kids feel they are being bullied, experts say they should go to a trusted adult for help and tell them truthfully what is going on. Bully Stoppers has a list of 25 Great Comeback Lines," that students can use when they are teased or harassed, ranging from "You really know your insults," to "The real you can't be this mean." The group also advises children to be accompanied by friends on the street or schoolyard, since bullies are more likely to prey on children who are alone. Parents should be alert to signs their children are being bullied. If there's a problem, they should discuss it with a teacher, guidance counselor or school administrator. It helps if the parents knows what school policies are in place to battle bullying. Some seemingly obvious responses to bullying prove counterproductive, according to experts. Parents, should not, for example, suggest that their child try to avoid a bully or hit back. And parents should not approach the bully's parents, who will often simply take their child's side, leading, to further retaliation. |

At the same time, research has indicated how pervasive bullying is. A 2001 study of students in 8th through 11th grades by the American Association of University Women Educational Foundation found that "four of five students--boys and girls--report that they have experienced some type of sexual harassment in school."

A Los Angeles study of 192 sixth-graders concluded that almost half had been bullied at least once during a five-day period. "We knew a small group gets picked on regularly, but we � didn't know how much bullying we would find over a few random days," Jaana Juvonen, a UCLA professor of psychologist and co-author of the study, has said.

"Building Blocks to Safety," a Kaiser Family Foundation study of 8 to 15 year olds found that more students cited teasing and bullying as "big problems" than mentioned drugs, alcohol, racism, AIDS, or pressure to have sex.

Connie Cuttle, director of Student Engagement for the city Department of Education, said that national research shows that the problem peaks in the middle grades and starts to fall off in the ninth grade. Teacher Frank Jump agrees the problem reaches an apex in middle school. "They don't know what is going on with their bodies and it is out of control," he said. "They are also testing out how they are perceived by others and where they fit in the scheme," he said.

Victims of bullying feel sick more often than their classmates, get lower grades and miss more school, Adrienne Nishina, who also worked on the UCLA study, told Time magazine. But the bullying also has effects on the perpetrators, with studies finding that bullies are far more likely than other children to go on to delinquent and even criminal behavior. And students who simply witness bullying can feel angry and anxious. "When kids pay attention to their environment, witnessing bullying often makes them feel bad," Juvonen has said.

INSIDE NEW YORK'S CLASSROOMS

As an art and health teacher at Abraham Lincoln Middle School in Cypress Hills, Brooklyn, Jump sees more than his share of bullying. Most of it is racially motivated, he says, sometimes within the same race because someone is perceived to be "too white" or "too black."

"A girl in my sixth grade class who was tall and dark was getting picked on by black kids who called her 'burnt cookie.' I would intervene and say, 'Excuse me. I can't believe this is happening in my classroom,'" Jump said. "I ended up telling the girl, 'They hate you because you are beautiful,' and that became her defense. She started looking at herself more closely and saying, 'Maybe I am beautiful.'"

Jump says that in classes with very low functioning students, "bullying is almost constant. I have one class where it is such a problem that I can barely teach a lesson."

Youth Communications, which works with city teenagers, has compiled "Sticks and Stones," a collection of essays on bullying. In one, Nadishia Forbes writes that, growing up in the Caribbean, "I never really worried about whether my clothes matched." But she continues, in a New York junior high school she became a "perfect target" because of her immigrant status and the way she dressed. The bullying escalated from giggles and pointing to having "kick me" signs stuck on her back. "I would go to school each day with my heart pounding," she wrote.

Writing from the other perspective, Julio Garcia acknowledges being part of a "pretty brutal" gang of 8 to 10 year olds, who "beat up smaller kids" and said "nasty, disrespectful things to women." He credits getting involved in karate with turning him away from bullying. "At the dojo," he wrote of the karate training hall, "I learned respect for people and objects."

POLITICAL ACTION

The city's school discipline code, (in pdf format) which describes violations ranging from cutting class to shooting someone, bans bullying. It bars students from "engaging in intimidation and bullying behavior, threatening, stalking or seeking to coerce or compel a student or staff member to do something; engaging in verbal or physical conduct that threatens another with harm, including intimidation through the use of epithets or slurs involving race, ethnicity, national origin, religion, religious practices, gender, gender identity, sexual orientation or disability."

But some advocacy groups and City Council members felt this was not enough. So, last July, the council passed an anti-bullying bill, the Dignity for All Students Act. It requires the city Department of Education to establish policies and guidelines that prohibit harassment and bullying, and to create a system for tracking and reporting incidents.

City Councilmember Alan Gerson, the main sponsor of the bill, said it responds to deficiencies in the discipline code. "Teachers tell us that they don't have the supportive mechanisms necessary to deal with the problem of bullying and that they are pressured not to report things because it would make the school look bad," he said

Mayor Michael Bloomberg ridiculed the council measure as "silly" and vetoed it. After the council overrode the veto, the administration declared the law "illegal" and refused to enforce it. Councilmember Alan Gerson said the council is preparing to go to court to get the administration to comply with the law.

The general counsel to the city education department, Michael Best, said the state's existing Safe Schools Against Violence in Education law pre-empts the city law. But supporters of the Dignity for All Students Act say that, unlike the city law, the existing state law does not specifically address bias-related harassment and attacks.

Advocates have proposed a state Dignity for All Students Act. The Democrat-controlled State Assembly overwhelmingly passes it every year, but the Republican-led Senate objects to listing categories of protection in the bill--especially "sexual orientation" and "gender identity" and expression. The Bloomberg administration says it supports the state version of the bill, even as it refuses to implement the city measure, which has many similar requirements for reporting, intervention, and training.

Bully Police USA, a group that monitors efforts to deal with bullying, gives New York State a grade of F on the issue. "If a state doesn't have a law, it is a crapshoot to see how the individual school or even a district will address the problem," says Tom Letson, a middle school counselor in New Jersey who works with an organization called Bully Stoppers.

WHAT THE CITY DOES

The city Department of Education catalogued 1,769 incidents of harassment in New York City public schools last year �- an average of about one and a half per school. The department only counts incidents that require a police report.

Critics question how the number could be so low, but Rose Albanese-DePinto, director of School Intervention and Development insists "reporting must happen of all incidents." Students or parents are first supposed to report incidents to teachers who are supposed to convey them to principals who can make their reports in an online system.

Connie Cuttle said the education department has not collected any data on how bullying affects learning, absences, grades, and student mental health in New York City specifically.

Parents have testified about their frustration with getting school administrators to confront bullying. Malika Simmons, whose fourth-grade son attends PS 161 in Crown Heights, said her son was bullied continuously, but administrators would not intervene. "I feel bullied as a parent," she told the City Council.

Joy Tomchin, who has a 10-year old son at PS 41 in Greenwich Village, said her son was teased for being fat, a lavatory was designated the "faggot bathroom," and youngsters were bullied for being Asian, for their amounts of body hair, learning disabilities, being adopted, female, short, tall, or wearing the wrong clothes. Her complaints about such behavior, Tomchin said, "were met by silence."

Albanese-DePinto said parents who do not get satisfaction from their principal should go to regional superintendents or the central administration if necessary

Councilmember Gerson does see "greater attention within the [education] department" to bullying, which he attributes at least partly to the council's action.

The Department of Education trains staff in how to deal with conflict resolution and intergroup relations among students. It operates Harvey Milk High School for students harassed because they are or are perceived to be lesbian, gay, bisexual, or transgendered, an open admission that the school system is not safe for these students.

Cuttle said the city is trying to apply two national programs, one for elementary and middle schools and the other for high schools throughout the system. The department will train teams in every school to instruct the staff on these techniques.

Some of the anti-bullying programs derive from the work of Norwegian educator Dan Olweus, who called for involving the whole school. According to Tom Roderick, executive director of Educators for Social Responsibility-New York Metro, "we have to show the kids ways to be allies for kids being targeted. And...we have to provide individual counseling for both the bullies and the targets."

But anti-bullying programs cost money and take time. Since discussions of bullying inevitably deal with the sensitive issues of race, sex and sexual orientation, schools can be reluctant to confront it in the classroom.

While some studies question the effectiveness of such programs, other studies conducted in the 1990s in England and Norway found they could cut bullying by 30 percent to 50 percent.

"If we begin to evolve the youth culture to the point where it is cool to be empathetic, just as we have made progress on fighting drugs,� said Gerson, �we can succeed."

Liliya Kane's experience shows that some programs can work. In high school, she became involved with The Council for Unity, a program launched at Brooklyn's John Dewey High School after a violent racial incident in 1975. It provides training for students and teachers, stresses cultural awareness and offers mentoring programs. Kane said it has helped her. "My self- esteem and confidence improved a lot, if not soared," she said. "I regained pride in my culture and my nationality."