Dividing the Wealth: Who Gets the Council's Discretionary Funds?

Many of David Weprin's constituents would undoubtedly like to pat him on the back. By one measure, the mustachioed councilmember from Queens gained more funding for individually sponsored projects and initiatives than any of his 50 council colleagues, corralling more than $735,000 for nonprofits and community-driven organizations.

Gotham Gazette’s analysis of the City Council's so-called "pork-barrel" spending -- officially known as the member items list -- also found that newer members of the council, such as Mathieu Eugene and Darlene Mealy, both of Brooklyn, got far less funding for their individual initiatives.

This analysis is possible, because for the first time the council not only released pages upon pages of figures for these discretionary funds following the passage of the $59 billion fiscal 2008 budget, but also provided the names of the members who sponsored every item -- a move hailed by Council Speaker Christine Quinn as a way of opening up the city's budget process.

This year's revamped members' list makes at least one element of discretionary spending - besides Councilmember Charles Barron's affinity for rodeos - undeniably apparent: It is much easier to rake in the cash if you have seniority or a leadership position. (For a complete list of who got what, click here).

Following The Flow

The discretionary funds are just one of several ways council members "bring home the bacon."

According to city officials, each council member receives $340,464 in discretionary funds, of which $151,714 is devoted to youth programs in his or her district, $108,750 to senior initiatives and $80,000 to allocate as he or she sees fit. That funding for the entire council totals approximately $17.4 million.

Both the senior and youth initiatives are not included in this year's members' list, because appropriations have not yet been solidified, city officials said. Council members have an opportunity to lock down additional funding for their district through capital spending, which is also not included in the list.

Beyond that, the members' list does include the $80,000 each council member can use at his or her discretion as well as grants. The members lobby for these grants through letters of support, applauding the work of certain organizations and nonprofits that run social or community-driven programs. Much of the members' list is fueled by this procedure.

This year's discretionary funding includes a range of programs focused on such issues as fighting crime and reducing poverty. And, of course, the list is not without the odd, the quirky or the eyebrow-raising earmark (like $3,000 from Councilmember Robert Jackson for a Summer Scandinavian Music Festival in Fort Tryon Park or $4,000 to Cowboy Mania for rodeo costs from Brooklyn-based Barron). (For another somewhat unusual program see box.)

Some of this discretionary spending is signed by one councilmember, while other, typically larger earmarks include a number of sponsors.

Our analysis totals only the funding that each council member received through the members' list for items that he or she alone sponsored. It does not include the many projects with multiple council sponsors. Current council records provide no way of determining which council member was the lead sponsor of the items sponsored by two or more members. As a result, the totals do not include, for example, the largest appropriation - $600,000 to the Metropolitan Council on Jewish Poverty, which was sponsored by 15 council members.

And so, some council members who are not high on Gotham Gazette’s list could have directed more of their discretionary funds to larger projects, which tend to be sponsored by an array of members, instead of focusing on individual items.

And the size of the individual items varied from $1,000 to $600,000. Because of that, by another measure, Weprin is not number one. While he collected the most funding for individually sponsored initiatives at $736,500 in 31 separate line items, Queens Councilmember Leroy Comrie acquired the most individual items -- 80 totaling $710,857.

Although co-sponsored items are excluded, the analysis does offer insight into individually sponsored items, which total $11.6 million, nearly a third of the more than $36.4 million on the member’s item list.

|

Cick here for a complete chart.

***This chart includes the total funding allocated for each councilmember's individually sponsored items. The totals do not include any items that were co-sponsored by multiple council members or items signed by borough delegations. It represents approximately a third of the total members' list funding.

The Benefits of Seniority (Sometimes)

These individual items are merely one part of what each member contributed to a district, a borough or citywide project throughout the members' list. Weprin, for example, had 31 individually sponsored items, but signed on as a co-sponsor to 164 more initiatives.

Other names were scarce in comparison. Bayside Councilmember Tony Avella signed on to 9 items on his own and sponsored 26 other items with his colleagues.

Council members hovering near the top of the list tend to be incumbents, chair the council's most influential committees or are thought to be seeking higher office in the next citywide election in 2009.

Some of the members who got less than $100,000 in individually sponsored items are newcomers to the council or sit on less active committees. Many also signed on to initiatives endorsed by multiple council members or sponsored by borough delegations.

Manhattan Councilmember Alan Gerson accumulated 12 individually sponsored items totaling $63,000. Even so, according to Gerson's Deputy Chief of Staff Sayar Lonial, the councilmember contributed to approximately $4.5 million worth of initiatives with his colleagues, leaving him "pleased" with his appropriations.

"From our perspective, it's more about the groups getting the money than who gets the credit," said Lonial. "We kind of feel like it's a council team effort."

Others on the lower end of the funding spectrum, however, attribute their relative lack of individual cash to how willing they were to comply with the council speaker's agenda.

Who’s In and Who’s Out?

|

Dollars for Bats Councilman James Oddo, famed for his defeat of aluminum baseball bats, is putting his money where his mouth is. Among his discretionary member allocations for fiscal year 2008, the council minority leader included $5,000 for a “Wooden Bat Baseball Tournament.” The tournament, which includes several league-wide game days, has already taken place throughout Oddo’s home borough of Staten Island,. Each player in the major division of their local Little League receives and must use a wooden bat. The program has helped provide free wooden bats for several hundred young baseball players. Michael Scerbo, who organized the wooden bat days, said that giving the players something they could keep was important in getting them ready for the rest of their baseball careers. Given the ban on aluminum bats in high school games, the young player will probably have to use wooden bats. “Kids should get used to the bats now.…and be ready to use them,” Scerbo said., --Brian Bonci |

Those in council leadership positions tend to be at the higher end of the funding spectrum. That, observers said, is not unusual.

"I think there is an element that is unavoidable in member item processes," said Megan Quattlebaum, the associate director of Common Cause/NY. "They tend to be fairly leadership controlled. So the rank and file lawmakers who have been around longer, who have earned the favor of leadership, tend to do better. That’s why transparency is so important."

Coming in third with just over $700,000, Lewis Fidler, assistant majority leader and chair of the youth services committee, said he is proud to be considered the third "biggest pig" in the council.

And it's not just his leadership position that locked in his funding either, Fidler said. Although the council speaker can have ultimate veto power, Fidler said other people scrutinize the member items.

"Some of it gets decided by the member," Fidler explained. "Some of it gets decided by the borough delegation. Some of it gets decided by the speaker and some of it gets decided by the budget negotiating team." The process, he said, is multi-faceted.

Because of his role as chairman of the finance committee, Weprin said he ends up lobbying for groups that have been shortchanged, which contributes to his position at the head of the funding line. The finance chair said he also often serves as an advocate for organizations whose outreach extend far beyond his Queens district. For example, one of Weprin's most expensive items allocates $100,000 for New Yorkers for Parks for "The Daffodil Project" -- an initiative that commemorates 9/11 and draws attention to the needs of neglected parks in all five boroughs

He also acted as a liaison for the speaker's office, he added, advocating for groups on Quinn’s behalf and lobbying for groups on a citywide scale - all of which contributed to his topping the funding pool for individual items.

Weprin also recognized that the experience of a councilmember could dictate whether his or her projects are allocated in the members' list. "A lot of it is based on what's happened in the past," said Weprin, who has served in City Hall since 2002 and is running for city comptroller in 2009.

But some council members with as many years inside City Hall received far less than Weprin or Fidler.

Avella, who ranked in the bottom five on individually sponsored items, has also served on council since 2002. On one hand, he said the more funding a member gets, the better the individual looks when up for re-election or campaigning for higher office. But, on the other hand, the more funding a member receives, the more they are in the speaker's pocket, he said.

Avella, who serves as funding, zoning and franchises committee chair, said getting more funding "isn't worth selling your soul."

"There is a basic amount, but those that are looked upon favorably by the speaker get more," said Avella. "When you follow the leadership, you’re rewarded... Does it make it right? Absolutely not."

Other council members, like Comrie, claim the funding is apportioned by need.

"I have a working class district," said Comrie, who ranked second in funding for individually sponsored items. "I have one-parent families that can't afford to pay for after-school programs or sports programs. … I'm giving to anybody that has a volunteer group that is willing to give my seniors, my children, my adults the programs."

Beyond the needs of his district, Comrie said his position as majority whip and head of the Queens delegation also gives him an in to preliminary discussions on funding. "(I'm) definitely part of the planning and developing of the agenda," Comrie said. "I get to put my two cents in early and often."

Funding in the Future

Whether it is influence, seniority or submission that gets some council members certain projects and skips over others, the 2008 members' list still opens the door to more disclosure in the City Council. Council members contrast their disclosure with the state legislators in Albany, whose pork barrel spending is largely shielded from public view, and with that of other legislatures in the country.

Some advocates would like to see more disclosure at City Hall such as more information on which councilmember is spearheading each co-sponsored initiative. But several council members said the city is certainly heading in the right direction.

"It's the first time we actually did this," Weprin said of the inclusion of names with members' items. "We are open to suggestions for future years, and the intent is to be more transparent."

Income Numbers Show a Changing City

Incomes rose the most in the Bronx? The growth in earnings in manufacturing surpassed that for finance and information? New York City residents fared better than higher income commuters?

These sound like trends that might have occurred in decades past. Actually, though, they happened fairly recently -- from 2000 to 2005 -- according to the personal income series compiled by the U.S. Commerce Department. The Commerce Department's Bureau of Economic Analysisputs this report together using tax records and state administrative records on employment. You rarely read about such data in news reports, partly because the information is only annual, and there is a lag between the period of time covered by the data and its release. But despite that, this data tell us important things about the economy.

In 2005, the total personal income of New York City residents was $343.4 billion. This was 16 percent greater than in 2000, before adjusting for inflation. Since the city's population grew by 2.4 percent from 2000 to 2005, per capita income increased 13.3 percent. For the first half of this period (through mid-2003), the city's economy was declining. The downturn resulted from the national recession, the aftermath of 9/11 and the bursting of the Wall Street and technology bubbles. But the city's economy started to recover in the last half of 2003, and by 2005, total employment in the city had recovered although real total personal income (i.e., after adjusting for inflation) did not regain the 2000 level until 2006.

Consumer inflation was 3.8 percent in 2006, and the city's Office of Management and Budget projects that personal income increased by 6.6 percent in 2006.

EARNINGS FOR THOSE WORKING IN NEW YORK CITY

Personal income counts the income of all persons from all sources. It includes wages and salaries, proprietors' income, employer-provided health insurance, dividends and interest income, social security benefits, and other types of income. By far the largest component of personal income is a category called "earnings," which includes wages and salaries, and proprietors' income. In New York City in 2005, earnings totaled $351.7 billion. This exceeded residentsĂ total personal income of $343.4 billion because commuters who live outside the city took home nearly a quarter (24 percent or $83 billion) of the earnings generated in the five boroughs. Employee compensation accounted for 86 percent of New York City earnings by place of work and proprietors' income was the remaining 14 percent.

From 2000 to 2005, net earnings received by city residents grew more than twice as fast as earnings of commuters (an increase of 17 percent versus 7 percent). This reflects the fact that a lot of the jobs lost during the downturn early in the decade occurred in high-paying industries such as financial services, information and professional services that tend to have high concentrations of commuters. Also, much of the employment growth in the first half of this decade was in health, social and educational services, industries that tend to employ proportionately more city residents than commuters.

Employer contributions for pension and health insurance ñ which are included as employee compensation -- increased by nearly a third from 2000 to 2005 or more than three times as fast as the growth in wages and salaries, reflecting the steep rise in health insurance costs.

SELF-EMPLOYMENT UP, WAGE AND SALARY EMPLOYMENT DOWN

One of the unique features of the personal income series is that it includes data on the number and earnings of those who are self-employed. Self-employment grew rapidly in New York City from 2000 to 2005, increasing by 37 percent, reflecting an increase of 207,000 persons. On the other hand, New York City wage and salary employment registered a decline of 3 percent, or 120,000, over this period. A part of this spurt in self-employment results from the practice by some businesses of improperly classifying their workers as independent contractors. Since 2000, the earnings of the self-employed grew only half as fast as the number self-employed (18 percent vs. 37 percent). For wage and salary workers, total employee compensation (wages plus employer contributions) increased by 14 percent even though their number declined by 3 percent.

THE MAJOR COMPONENTS OF PERSONAL INCOME

The table below shows the three main categories of resident personal income, their shares of the total, and the 2000-to-2005 growth rates for each. (Capital gains, from stock or real estate are not considered "income" in this set of statistics, but are considered changes in the value of an asset.) The decline in interest rates largely accounts for the decline in the dividends, interest, and rent income.

Transfer payments come to city residents from state and federal social insurance and safety net programs. They increased by 30 percent from 2000 to 2005, largely because of the increase in Medicare and Medicaid payments. Medicare grew by 50 percent and Medicaid increased by one-third over this five-year period. These sizable increases have been due to rising health care costs as well as significant growth in the number of beneficiaries, particularly for Medicaid. Medicare and Medicaid payments go to health care providers and the total amount is nearly four times as great as the Social Security benefits paid to city residents. In 2005, city residents received $11.1 billion in Social Security while Medicare payments to health care providers in New York City totaled $12.8 billion and federal and state Medicaid payments to city providers totaled $27.7 billion.

The fourth major category of transfer payments includes various income maintenance benefits, which total $8.9 billion. Here the largest category includes the Earned Income Tax Credit, which gained by 44 percent from 2000 to 2005 and was $3 billion in 2005. Federal food stamp benefits totaled $1.4 billion in 2005, 50 percent higher than five years earlier, a growth that reflects improved enrollment procedures and a high level of continuing means-tested need in New York City.

Unemployment insurance was designed to function as an ìautomatic stabilizerî during economic downturns to help laid-off workers maintain some level of purchasing power. The income data bear this out. During the recession, unemployment compensation nearly tripled, rising from $800 million in 2002 to $2.2 billion in 2002. By the time the recovery was well underway in 2005, unemployment benefits had receded to $1.1 billion.

EARNINGS BY INDUSTRY: THE EXPECTED AND THE UNEXPECTED

The income series includes figures on earnings (wages and salaries, and proprietorsĂ income) by industry, but only for the 2001 to 2005 period. Overall earnings increased by 12.4 percent over these four years. Among the larger industry groupings, private educational services registered the fastest growth, with earnings increasing by 37 percent. Health care and social assistance came in second with a 24 percent increase. Four sectors had 21 percent gains: real estate, retail trade, arts and entertainment, and accommodation and food services. While the number of jobs in the manufacturing sector declined sharply, earnings increased by 11 percent -- several times faster than the 3 percent growth in finance and insurance sector.

The information sector had a 10 percent increase in earnings over the four years from 2001 to 2005, although the pattern for individual industries in this sector varied. Earnings in broadcasting gained by 39 percent, while motion picture production had a 9 percent drop in earnings, telecommunications a 10 percent earnings decline, and earnings for those working for Internet service providers and related activities fell by 22 percent.

BRONX LEADS THE WAY

One of the most interesting trends that emerges from the personal income data for 2000 to 2005 is that the ever-resilient Bronx had the most impressive income and earnings growth among the five boroughs. As the table below demonstrates, people living in the Bronx experienced total income growth of 24 percent over this period, half again as high as the cityĂs overall 16 percent income growth. On a per capita basis, incomes grew by 21.5 percent in the Bronx, also outpacing the other boroughs, although it still has the lowest per capita income -- $23,513 compared to the citywide average of $41,803. Jobs and businesses located in the Bronx showed similar gains, with earnings growing at twice the citywide rate. Brooklyn came in second for these three measures and Manhattan brought up the rear.

The relatively faster income growth in the Bronx, Brooklyn and Queens over the 2000 to 2005 period is largely due to New YorkĂs changing job picture and who has benefited from it. The number of jobs in health, education and social services has grown, and these industries are more likely to employ outer borough residents. On the other hand, Manhattanites, like commuters, are more likely to hold jobs in higher-paying financial services, a sector that has recovered somewhat but was hard hit by the recession and the bursting of the Wall Street and dot.com bubbles.

Health, education and social services now account for 10 times more earning in the Bronx than manufacturing does and provide 36 percent of total earnings from jobs in that borough. Earnings from the banking industry were flat in Manhattan, where most bank headquarters are located, but rose appreciably in other boroughs ñ by a huge 83 percent in the Bronx, for example ñ because of an increase in the size and number of branch banks. Brooklyn also saw strong earnings growth related to the relocation of some financial securities operations from Manhattan in the wake of 9/11.

Despite all this, Manhattan residents still have far higher income level than the residents of the other four boroughs. Even with many low-income residents, Manhattan's per capita income level was $93,400 in 2005, two-and-half to three-and-a-half times the per capita income levels for the other boroughs. All indications from other sources, including tax data, suggest that incomes at the top of the distribution have been growing rapidly since the recovery got underway. A future column will examine trends in New York City's income distribution.

James Parrott is deputy director and chief economist of the Fiscal Policy Institute (www.fiscalpolicy.org). He has been studying and writing about the New York economy since he landed in New York City a quarter century ago.Â

No Quick Riches for New York's Twentysomethings

After years of expensive education,

a car full of books and anticipation,

I’m an expert on Shakespeare and that’s a hell - a lot

but the world don't need scholars as much as I thought.

Jamie Collum’s “Twentysomething,” a wry anthem of the newly graduated, describes the fate of many of New York City’s twentysomethings better than some of the rosy pronouncements heard recently. While USA Today and others claim that this is a banner year for graduates, the good news mainly applies to students in several specialty fields, such as business, engineering, computer science and nursing. And the gains are more pronounced among recent graduates of prestige universities.

While young people with bachelor’s degrees in business, accounting and engineering command salaries of about $50,000, most of this year’s liberal arts graduates will see a salary of about $31,000 -- similar to the pay received by a starting public-school teacher. This represents a decline of 1 percent since last year.

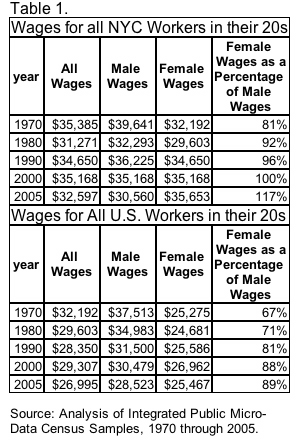

For those with all levels of education, including college and beyond, wages today have yet to catch up with the “real” wages (in other words, adjusted for inflation) that twentysomethings received in 1970. Men have seen their real wages fall substantially and women outside of New York have seen only very modest gain. Table 1 presents median wage figures, taken from Census data, for all full-time workers in their 20s from 1970 through 2005. Wages for all twentysomethings in New York City and in the United States are still below those received in 1970.

Over this period, women in New York City saw an amazing jump in their wages compared with those of men in their age group. While women in the city earned, on average about $7,000 less than men in 1970, by 2005 they made about $5,000 more. Interestingly, women in the country as a whole have closed the gap between their earning and those of men, but still lag behind.

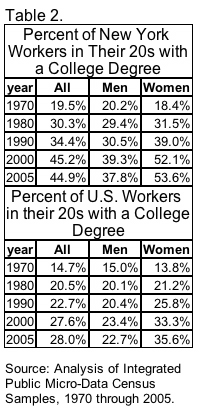

At the same time, as Table 2 shows, women eclipsed men in the proportion who were at least college educated by 1980. In New York City, over 53 percent of working women in their twenties have at least a college education compared to about 38 percent for men. Although working women in their 20s across the country are much more highly educated than are men, women in New York City, particularly those in Manhattan, are much more likely to be single, earn more money, and have more education than women living in the rest of the United States.

At the same time, as Table 2 shows, women eclipsed men in the proportion who were at least college educated by 1980. In New York City, over 53 percent of working women in their twenties have at least a college education compared to about 38 percent for men. Although working women in their 20s across the country are much more highly educated than are men, women in New York City, particularly those in Manhattan, are much more likely to be single, earn more money, and have more education than women living in the rest of the United States.

The data show a number of other striking trends:

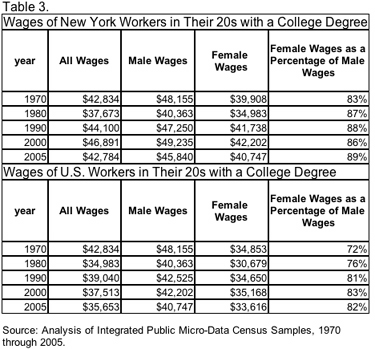

• For college graduate males, wages have declined in New York City and nationally, while women have had very modest gains in the city, but not in the U.S.

• For those with advanced levels of education (beyond a bachelors degree), wages of females have soared in NYC, while male wages have only crept up. Nationally, male wages have fallen, while female wages have stood still.

• For the college and even better educated, the wage gap between men and women declined, but it is still much smaller in New York City than nationally.

Furthermore, the gap between the wages of the most highly paid and the least highly paid of the college graduates in their 20s increased, as well. In 1970, those in the top quarter made at least $53,476. By 2005 that figure grew to $61,120. But those in the bottom quarter, who in 1970 made at most $35,917, saw their wages drop to $35,560 by 2005. So even among the young, affluent New Yorkers are becoming even more affluent, while the less affluent are not even holding their own. For those with education beyond college, the pattern is very similar: Those in the top quarter in 2005 made at least $77,419 up from $67,577, while those in bottom quarter made no more than $42,784 only slightly more than $41,504, the amount that they made in 1970.

In short, the lyric of Collum’s “Twentysomething” hits the mark for many in New York City as the picture is far from cheerful. But they have some consolation. If young males with a college or better education in New York City and the United States have seen their wages decline, those without college are much worse off. It may not better today than it was 35 years ago to be a college graduate twentysomething, but it is certainly better than being a twentysomething without a college degree.

Andrew A. Beveridge has taught sociology at Queens College since 1981, done demographic analyses for the New York Times since 1993, and been in charge of Gotham Gazette's demographics topic page since 2000. The opinions expressed are his alone.